Update: I’m reposting this on July 20 because these warrants have been re-released in less redacted form. As noted below in the update on Section C, that previously redacted section does pertain to Michael Cohen’s hush payments to Stormy Daniels, meaning the only mention of the Steele Dossier in the earliest warrant on Cohen is just to a post-dossier WSJ article used exclusively to explain Cohen’s own description of how he served as Trump’s fixer.

Because the frothy right thinks it’s an important question but won’t actually consult the public record, I’m doing a series on what that public record says about the relationship between the allegations in the Steele dossier and the known investigative steps against Trump’s associates. In this post, I argued that the way the Steele dossier influenced the Carter Page investigation may be slightly different than generally understood: it appears that the dossier appeared to predict — just like George Papadopoulos had — the release of the DNC emails on July 22. From that point forward, Page continued to do things — such as telling people in Moscow he was representing Donald Trump in December 2016, including on Ukraine policy — that were consistent with the general theory (though not the specific facts) laid out in the Steele dossier. That is, Page kept acting like the the Steele dossier said he would. That said, the government had plenty of reason before the Steele dossier to investigate Page for his stated willingness to share information with Russian spies, and his ongoing behavior continued to give them reason.

I’m more interested in the example of Michael Cohen.

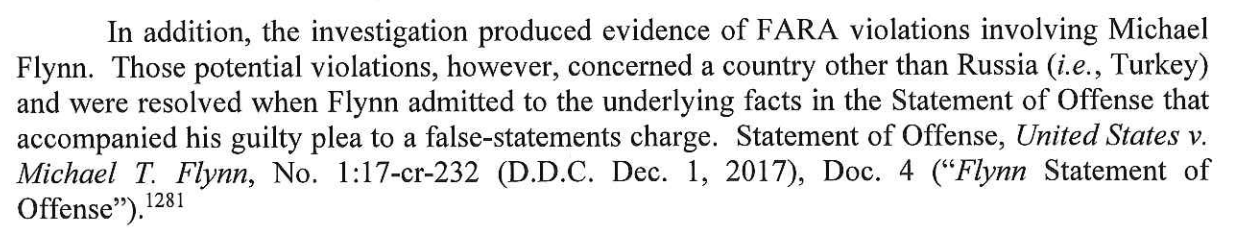

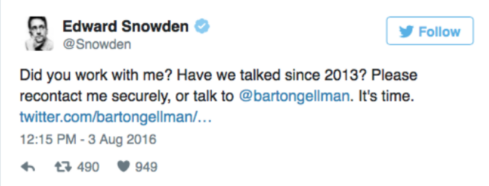

The Steele dossier eventually describes Michael Cohen as the villain of coordination with Russia

The dossier makes allegations against Cohen four times, all after the time when Steele and Fusion GPS were shopping the dossier to the press, increasing the likelihood Russia got wind of the project and were shopping disinformation.

The first three mentions came on three consecutive days (probably based on just two sub-source to Kremlin insider conversations), all apparently sourced to the same second-hand access to a Kremlin insider, and evolving significantly over those three days. Importantly, the sub-source is also the source for the claim that Page had been offered the brokerage of the publicly announced Rosneft sale, meaning this person purportedly had access to Igor Sechin and a Kremlin insider, and if this source was intentionally feeding disinformation, it would account for the most obviously suspect claims in the dossier.

October 18, 2016 (134): A Kremlin insider tells the sub-source that Michael Cohen was playing a key role in the Trump campaign’s relationship with the Kremlin.

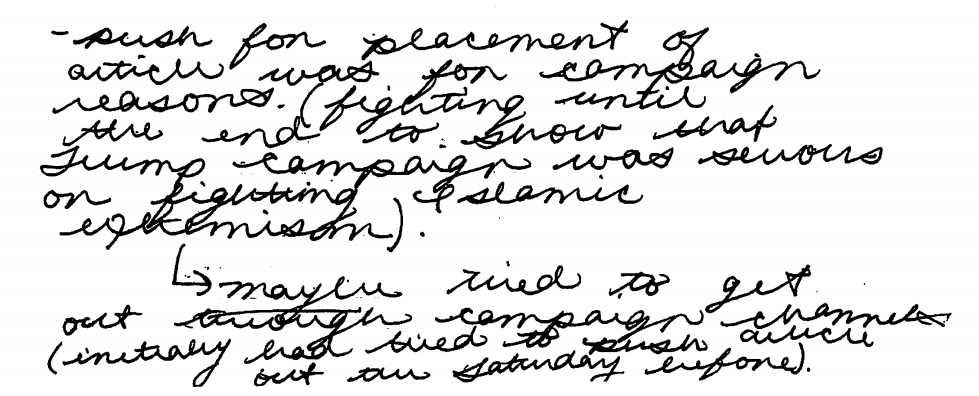

October 19, 2016 (135): The Kremlin insider tells his source that Cohen met with Presidential Administration officials in August 2016 to discuss how to contain Manafort’s Russia/Ukraine scandal and Page’s secret meetings with Russian leaders. Since that August meeting Trump-Russian conversations increasingly took place via pro-government policy institutes.

October 20, 2016 (136): In a communication that “had to be cryptic for security reasons,” a Kremlin insider tells a friend on October 19 that the reported meeting with Cohen took place in Prague using Rossotrudnichestvo as a cover. It involved Duma Head of Foreign Relations Committee Konstantin Kosachev. This is notably different from the PA claim made just the day before.

Then there’s the final report, which Steele has claimed was provided for “free,” dated after David Corn and Kurt Eichenwald’s exposure of the dossier, after the election, after the Obama Administration ratcheted up the investigation on December 9, and after Steele had interested John McCain in the dossier. In addition to offering a report that seems to project blame onto Webzilla for what the Internet Research Agency did, this report alleges what would be a veritable smoking gun, missing from the earlier reports: that Cohen had helped pay for the hackers.

December 13, 2016 (166): The August meeting in Prague was no longer about how to manage the Manafort and Page scandals, but instead to figure out how to make deniable cash payments to hackers (located in Europe, including Romania, where the original Guccifer had come from, not Russia), who were managed by the Presidential Administration, not GRU.

This December report is really the only one that claims Trump had a criminal role in the hack-and-leak, but the claims in the report all engage with already public claims: situating the hackers where the persona Guccifer 2.0 claimed to be from, Romania, suggesting the hackers were independent hackers who had to be paid rather than Russian military officers, and blaming Webzilla rather than Internet Research Agency for disinformation. That is, more than any other, this report looks like it was tailored to the Russian cover story.

The way this story evolved over time should have raised concerns, as should have other obvious problems with the December report. But it’s worth noting that there are two grains of truth in it. Cohen had been the key interlocutor between the Trump campaign and the Presidential Administration during the campaign, but to discuss the building of a Trump Tower in Moscow in January, not how to steal the election in October. Few people (at least in the US) should have known that he had played that interlocutor role; how many knew in Russia is something else entirely. Cohen was also someone that people who had done business with Trump Organization, like Giorgi Rtslchiladze and people associated with Aras Agalarov’s Crocus Group, would know to be Trump’s fixer. That fact would have been far more widely known.

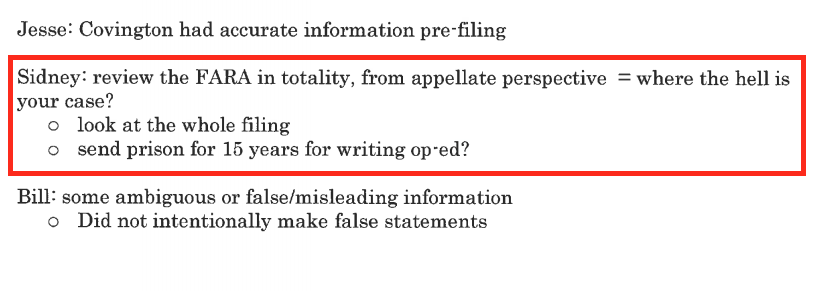

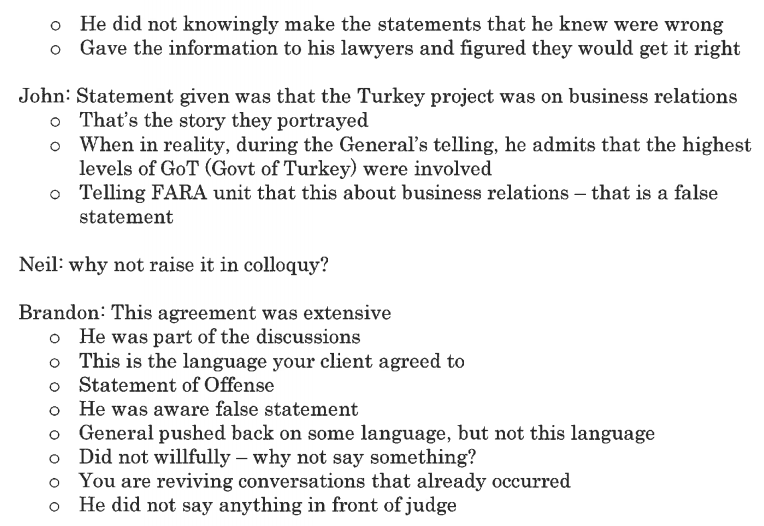

Nevertheless, by the end of it, Cohen was the biggest Trump-associate villain in the Steele dossier. If the Steele dossier had been directing the investigative priorities of the FBI, then Cohen should have been a focus for his role in the hack-and-leak as soon as the FBI received this report. Nothing in the public record suggests that happened. Indeed, at the time the FBI briefed the Gang of Eight on March 9, 2017, Cohen was not among the people described as subjects. Just Roger Stone had been added to the initial four subjects (Page, Manafort, George Papadopoulos, and Mike Flynn) by that point. Congress, including the Devin Nunes-led House Intelligence Committee, would focus closely on Cohen more quickly than the FBI appears to have.

That’s true even though Cohen was doing some of the things he would later be investigated for, including — immediately after the election — establishing financial ties with Viktor Vekselberg even while Felix Sater pitched him on a Ukraine deal.

Suspicious Activity Reports and the investigation into Cohen

The investigation into Cohen appears to have started — given this July 18, 2017 warrant application — as an investigation into suspicious payments, both Cohen’s payments to Stormy Daniels and payments from large, often foreign companies, particularly Columbus Nova, with which Viktor Vekelsberg has close ties, but also including Novartis, Korean Airlines, and Kazkommertsnank. The investigation probably started based off a Suspicious Activity Report submitted by First Republic Bank, where Cohen had multiple accounts, including one for Essential Consulting, where those foreign payments were deposited.

Cohen opened that Essential Consultants account on October 26, 2016, ostensibly to collect fees for domestic real estate consulting work, but in fact to pay off Stormy Daniels. His use of it to accept all those foreign payments would have properly attracted attention and a SAR from the bank under Know Your Customer mandates, particularly with his political exposure through Trump. Sometime in June 2017, First Republic submitted the first of at least three SARs on this account, covering seven months of activity on the account; that SAR and a later one was subsequently made unavailable in the Treasury system as part of a sensitive investigation, which led to a big stink in 2018 and ultimately to charges against an IRS investigator who leaked the other reports. The language of the third one appears to closely match the language in the warrant applications, including a reference to Viktor Vekselberg’s donations to Trump’s inauguration.

The first warrant application against Cohen

On June 21, the FBI served a preservation request to Google for his Gmail and to Microsoft for Cohen’s Trump Organization emails (see this post for the significance of Microsoft’s role). Generally that suggests that already by that point, FBI decided they would likely want that email, but needed to put together the case to get it. The preservation order on Microsoft suggests they may have worried that people at Trump’s company might destroy damning emails. It also suggests the FBI knew that there was something damaging in those emails, which almost certainly came in part from contact information the bank had and call records showing contacts with Felix Sater and Columbus Nova; it might also suggest the NSA may have intercepted some of Cohen’s contacts with Russians in normal collection targeting those Russians.

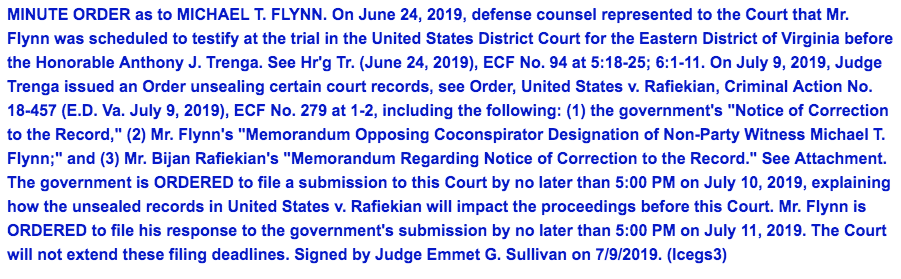

That July 2017 warrant (confirmed in later warrants to be the first one used against Cohen) lists Acting as a Foreign Agent (18 USC 951) and false statements to a financial institution. It explains:

[T]he FBI is investigating COHEN in connection with, inter alia, statements he made to a known financial institution (hereinafter “Bank 1”) in the course of opening a bank account held in the name of Essential Consultants, LLC and controlled by COHEN. The FBI is also investigating COHEN in connection with funds he received from entities controlled by foreign governments and/or foreign principals, and the activities he engaged in in the United States on their behalf without properly disclosing such relationships to the United States government.

In other words, the predicate for the investigation was his bank account — one in conjunction with which he would eventually plead guilty to several crimes — not the dossier. Had Cohen told the truth about why he was opening that bank account (to pay off the candidate’s former sex partners!), had he not conducted his international graft with it, had he been honest he was going to be accepting large payments from foreign companies, then he might not have been investigated. It’s possible that the public reporting on the dossier made the bank pay more attention, but his actions already reached the level that the bank was required to report it.

In the unredacted parts of the application, there is one citation of the dossier, but only to the title of a WSJ report on Cohen written in the wake of the dossier release, “Intelligence Dossier Puts Longtime Trump Fixer in Spotlight.” It uses the article in a section introducing who he is to cite Cohen explaining that he’s Trump’s “fìx-it guy . . . . Anything that [then-President-elect Trump] needs to be done, any issues that concern him, I handle,” not to describe any allegations in the dossier.

From there, it introduces the bank account, Essential Consulting.

Redacted section C

Update, 7/19: These warrants have now been unsealed, and — as media outlets originally reported — this section is about the hush payment to Stormy Daniels. The section also confirms that much of this investigation came from the KYC work of Cohen’s bank. I’ve marked the paragraphs that consider the possibility this section pertains to Russia with strike-through text.

The next section, C, is six paragraphs long (¶¶13 to 18), and remains entirely redacted. If the substance of the dossier appears in the warrant application, it would appear here. But such a redacted passage does not appear at all in a search warrant application for Paul Manafort from May, and no redacted passage appears as prominently in a Manafort warrant application from ten days later — which describes his relationship with three Russian oligarchs and the June 9 meeting — though there is a six page redaction describing the investigative interest in the June 9 meeting. The difference is significant because the dossier alleged that Manafort was managing relations with Russia until he left the campaign (including during June), so if there were redacted language about the dossier on Cohen, we would expect it to play a similar role in applications on Manafort, but nothing public suggests it does.

Some background on this redacted section. We got the Mueller-related warrants on Cohen because a bunch of media outlets asked Chief Judge Beryl Howell to liberate them on March 26, the week after Mueller officially finished his investigation. At first, Jonathan Kravis, the DC AUSA who has taken the lead in much of the ongoing Mueller word, noticed an appearance to respond. But it was actually Thomas McKay, one of the SDNY AUSA who prosecuted Cohen there, who responded to the request, along with another SDNY attorney.

Although the Warrant Materials were sought and obtained by the Special Counsel’s Office (“SCO”), the Government is represented in this matter by the undersigned attorneys from the United States Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of New York (“SDNY”), as the SCO’s investigation is now complete.

They argue that they’re willing to release the warrant materials under terms consistent with the terms used in SDNY, where information about the FBI affiants and information we know deals with the hush payments investigation got redacted.

Judge Pauley ruled that “the portions of the Materials relating to Cohen’s campaign finance crimes shall be redacted” to protect an ongoing law enforcement investigation, along with “the paragraphs of the search warrant affidavits describing the agents’ experience or law enforcement techniques and procedures.” Cohen, 2019 WL 472577, at *6. By contrast, Judge Pauley ordered that the portions of the materials that did not relate to the campaign finance investigation be unsealed, subject to limited redactions to protect the privacy interests of certain uncharged third parties. Id. at *6-7. Judge Pauley’s decision in these respects is also consistent with prior decisions of this Court, which have recognized the distinction between law enforcement interests in ongoing, as opposed to closed, investigations, as well as the importance of respecting privacy concerns for uncharged third parties. See, e.g., Matter of the Application of WP Company LLC, 16-mc-351 (BAH), 2016 WL 1604976, at *2 & n.2 (D.D.C. Apr. 1, 2016).

Consistent with the foregoing, the Government does not oppose the Petitioners’ request for partial unsealing, but respectfully requests that the Court authorize redactions consistent with those authorized by Judge Pauley in the SDNY litigation.

Because of this language, some people assume the redacted passage C relates to the hush payments, which were, after all, the reason Cohen opened the account in the first place. That may well be the case: if so, the logic of the warrant application would flow like this:

A: Michael Cohen

B: Essential Consultants, LLC

C: Use of Essential Consultants to pay hush payments

[Later warrants would include a new section, D, that described Cohen’s lies about his net worth to First Republic]

D: Foreign Transactions in the Essential Consultants Account with a Russian Nexus

i. Deposits by Columbus Nova, LLC

ii. Plan to Life Russian Sanctions

E: Other Foreign Transactions in the Essential Consultants Account

That would explain McKay’s role in submitting the redactions, as well as his discussion of redacting the warrant consistent with what was done in SDNY, to protect ongoing investigations. (The government will have to provide a status report in August on whether these files still need to be redacted.)

That said, it was not until April 7, 2018 that anyone first asked for a warrant to access Cohen’s email accounts in conjunction with the campaign finance crimes. And some SARs submitted in conjunction with the hush payments, such as one associated with the $130,000 payment on October 27, 2016 to then Daniels lawyer Keith Davidson and one from JP Morgan Chase reflecting the transfer from the Essentials Consulting account to Davidson’s were not restricted in May 2018 in conjunction with a sensitive investigation (nor was the third one reflecting the foreign payments described above), suggesting they weren’t the most sensitive bits in May 2018. Of note, the Elliot Broidy payments to Essential Consulting would post-date this period of the investigation.

That leaves a possibility (though not that likely of one) that Section C could describe the Russian investigation. The next passage after the redacted one describes the “foreign transactions in the Essential Consultants Account with a Russian nexus” (though, as noted, subsequent warrants describe Cohen’s lies in the following paragraph). It describes the $416,664 in payments from Columbus Nova, and describes the tie between Columbus Nova and Vekselberg. After introducing the payments, the affidavit describes the public report on a back channel peace plan pitched by Felix Sater on behalf of Ukrainian politician Andrii Artemenko.

Another possibility is that it describes Trump’s inauguration graft, which embroils Cohen and Broidy (though the investigation into Broidy is in EDNY, not SDNY).

Perhaps most likely, however, is that that section just describes other reasons why that Essential Consulting account merited a SAR. For example, it might describe how Cohen set up a shell company to register the company, something that doesn’t show up in the unredacted sections, but which is a key part of the hush payment prosecution.

If the section does not mention the Russian investigation generally (and the dossier specifically), then it means there is no substantive mention of it in the warrant at all, meaning it played at most a secondary role in the focus on Cohen.

As the timeline of the investigation into Cohen below shows, that redacted section would grow by one paragraph in the next warrant application, for Cohen’s Trump Organization emails, obtained just two weeks later. It would remain that length for all the other unsealed Mueller warrants.

Felix Sater and the investigation into Cohen

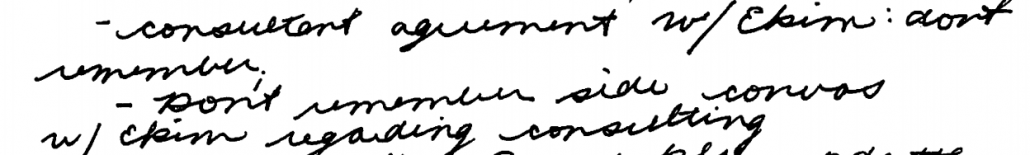

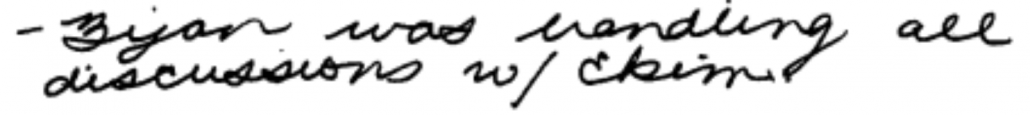

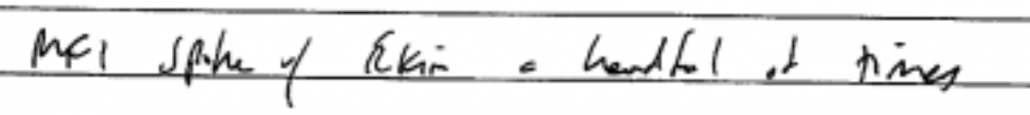

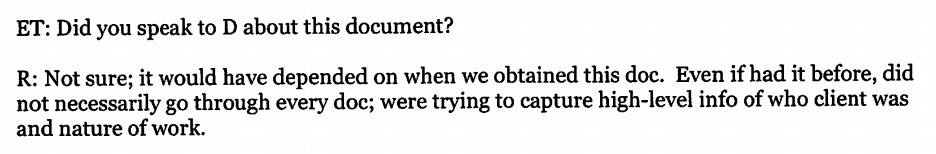

The way in which Sater is mentioned in the warrants against Cohen presents conflicting information about what might be in that redacted section. Significantly, Sater (described as Person 3) is introduced as if for the first time, in the discussion of the Ukrainian deal that appears after the redaction. That means that he doesn’t appear in the redacted material. That’s important because Sater would be one other possible focus of any introduction to why Cohen would become the focus of the Russian investigation (aside from the dossier).

The next warrant would also note numerous calls with Sater, reflecting legal process for call records not identified here (the government almost certainly had a PRTT on Cohen’s phones by then). But those calls, as described, were in early 2017 (tied to the suspected Ukrainian peace plan), not in 2015-2016 when the two men were discussing a Trump Tower Moscow.

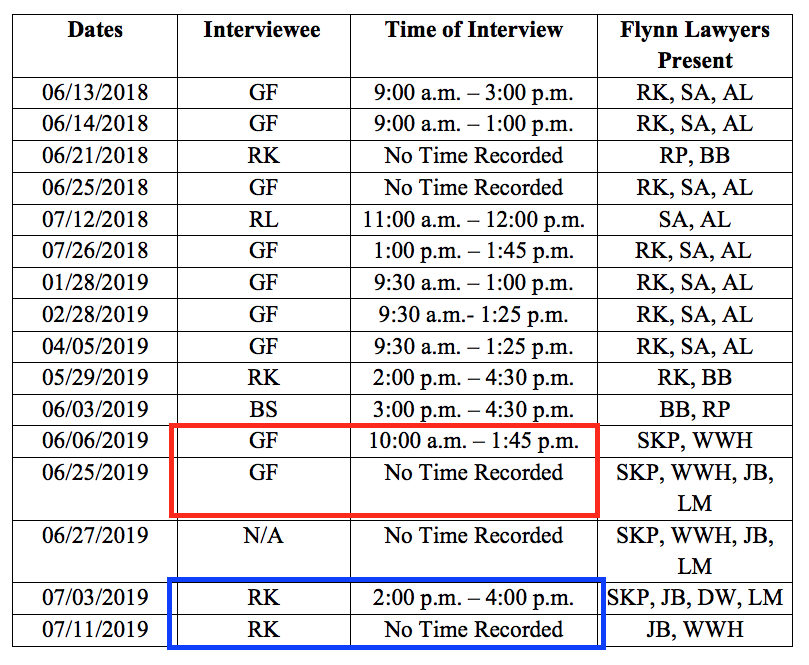

Mueller interviewed Sater on September 19, 2017, the first of two FBI interviews (he also appeared before the grand jury on an unknown date).

One of the most interesting changes to the Mueller warrants happens after that: In warrant applications submitted on November 13, the unredacted discussion of the Ukraine peace deal gets dropped. It’s unlikely Mueller’s investigation of it was eliminated entirely, because Mike Flynn, who allegedly ultimately received that deal, is not known to have been cooperating yet (his first known proffer was three days later, on November 16), and Mueller was still interested in interviewing Andrii Artemenko — the Ukrainian politician who pitched the deal — in June 2018.

In addition, based off the details in the Mueller Report cited to Sater’s September interview, Mueller was already investigating the Trump Tower deal. That suggests both topics — the Trump Tower deal and the Ukranian peace pitch — could appear in the redacted passage. Indeed, while the unredacted passages don’t explain it, one important reason to obtain the earlier emails would be to obtain the communications between Sater and Cohen during that period.

None of these warrants explain why Mueller became convinced that Cohen had lied to Congress, but by the second December interview of Sater, he presumably knew that Cohen had lied. But he probably didn’t have all the documents on the deal until he subpoenaed Trump Organization in March 2018.

All of which is to say, the treatment of the warrants’ Sater’s ties to Cohen, so important in any consideration of Cohen’s ties to Russia, ultimately don’t help determine what’s in that section.

If Mueller obtained Cohen’s location data, it was only second-hand

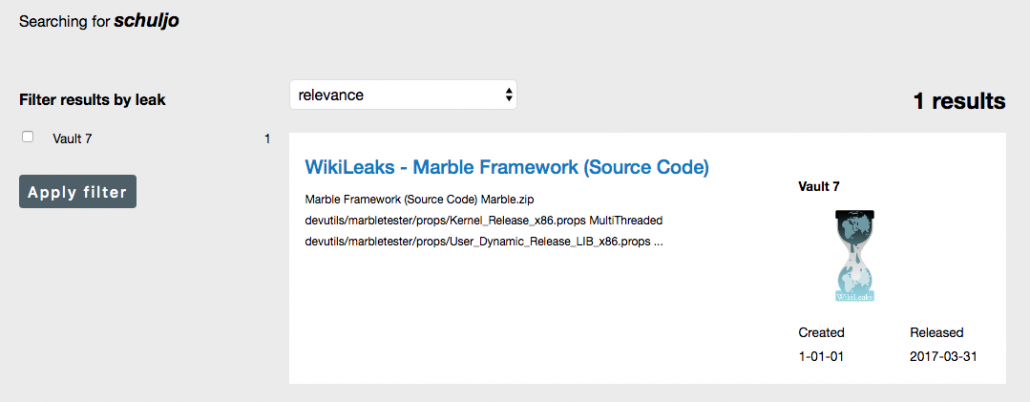

Finally, there’s one other detail not shown in the Mueller warrants you might expect to have if the Steele dossier was central to the Cohen investigation: a concerted effort to confirm his location during August 2016, when the dossier claimed he had been in Prague.

Granted, by obtaining records from Google, Mueller would get lots of information helpful to confirming location. For example, Google would have provided all the IP addresses from which Cohen accessed his account going back to January 2016. He would have obtained calendar data, if Cohen used that Google function. The warrant (as all warrants to Google would) asks for “evidence … to determine the geographic and chronological context of account access” and describes the various ways investigators can use Google to ID location (though it doesn’t specifically talk about location data in conjunction with Google Maps).

Mueller would get even more information from the Apple warrant obtained on August 7, 2017. The warrant for Cohen’s iCloud account on August 7 focused on a new iPhone (a 4s!!!) he obtained on September 28, 2016 and used for a function that gets redacted (which, again, could be the hush payments). It described his use of Dust and WhatsApp on the phone (Dust was what he used with Felix Sater), meaning one reason they were interested in the account was not for Cohen’s Apple content, but for anything associated with the apps he used on his phone (remember that Mueller got Manafort’s otherwise encrypted WhatsApp chats from Apple; the Apple specific language notes that some users back up their WhatsApp texts to iCloud). That said, the language on Apple (as all warrants on it would) specified that users sometimes capture location data with the apps on their phones.

Apple allows applications and websites to use information from cellular, Wi-Fi, Global Positioning System (“GPS”) networks, and Bluetooth, to determine a user’s approximate location.

This is a way the FBI has increasingly gotten location data in recent years, via the apps that access it from your phone. So the FBI would have gotten information that would have helped them rule out a Cohen trip to Prague in 2016.

That said, it’s not until April 7 that the government obtained the only known warrant for cell location data. That warrant focused only on the campaign finance crimes, and it obtained historical data only started on October 1, 2016 — pointedly excluding the August 2016 period when Steele’s dossier alleged Cohen was in Prague.

In short, along the way, Mueller obtained plenty of information that would help him exclude a Prague meeting (and subpoenas and other government information — such as his Homeland Security file — could have helped further exclude a meeting). But there’s no sign in the public record that Mueller investigated the Steele dossier Prague meeting itself.

To sum up: while it’s possible the redacted portions discuss Russia and therefore potentially the dossier. But there are a lot of reasons to think that’s not the case. It is hypothetically possible that between March (when FBI wasn’t investigating Cohen) and May (when Mueller took over) the FBI had done something to chase down the dossier allegations on Cohen. But, there’s no evidence that Mueller investigated them. On the contrary, it appears that the investigation into Cohen arose from the Bank Secrecy Act operating the way it is designed to — to alert the Feds to suspect activity in timely fashion.

In another world, that should placate the frothy right. After all, they complain that the dossier was used in Carter Page’s FISA application. You’d think they’d be happy that, in the eight months between the time FBI obtained that order and started investigating Cohen aggressively, they hadn’t predicated an investigation into the dossier. By that time, there were overt things — like Vekselberg’s donation to the inauguration and the Ukraine plan — that were suspect and grounded in direct evidence.

Timeline

May 18, 2017: Possible date for meeting involving Jay Sekulow, Trump, and Cohen.

May 31, 2017: Cohen and lawfirm subpoenaed by HPSCI.

June 2017: A SAR from Cohen’s bank reflects seven months of suspicious activity in conjunction with this Essential Consulting account

June 2017: Federal Agents review Cohen’s bank accounts.

June 21, 2017: FBI sends a preservation request to Microsoft for Cohen’s Trump Org account.

July 14, 2017: FBI sends a preservation request to Microsoft for all Trump Org accounts.

July 18, 2017: FBI obtains a warrant for Cohen’s Gmail account focused on FARA charges tied primarily to the Columbus Nova stuff, but also his other foreign payments). ¶¶13-18 redacted.

July 20, 2017 and July 25, 2017: Microsoft responds to grand jury subpoenas about both Cohen’s account and TrumpOrg domain generally.

August 1, 2017: FBI obtains a warrant for Cohen’s Trump Org email account (which they obtained from Microsoft), adding bank fraud, money laundering, and FARA (as distinct from 951) to potential charges. ¶¶13-19 redacted. ¶¶20 to 24 note irregularities in claims to First Republic. ¶28 details how Cohen and Andrew Intrater started texting in large amounts on November 8, 2016, showing over 230 calls and 950 texts between then and July 14, 2017. ¶30 includes email reflecting visit to Columbus Nova. ¶31 reflects probable subpoena to bank (rather than just SARs). ¶32 describes Renova paying Cohen through Columbus Nova. ¶36 reflects phone records showing 20 calls with Felix Sater between January 5, 2017 and February 20, 2017, and one with Flynn on January 11, 2017. ¶39, ¶41 include new evidence from Google search.

August 7, 2017: FBI obtains a warrant for Cohen’s Apple ID (tied to his Google email). ¶¶14-20 redacted. ¶50-54 describes Cohen obtaining a new Apple iPhone 4s on September 28, 2016 and using it for a redacted purpose. It describes Cohen downloading Dust (the same encrypted program he used with Felix Sater) the day he set up the phone, and downloading WhatsApp on February 7, 2017.

August 17, 2017: FBI obtains second warrant on Cohen’s Gmail, not publicly released, but identified in second Google warrant. It probably added wire fraud to existing charges being investigated.

August 27-28, 2017: Cohen conducts a preemptive limited hangout on the Trump Tower story feeding WaPo, WSJ, and NYT.

August 31, 2017: Cohen releases the letter his attorney had sent — two weeks earlier — along with two earlier tranches of documents for Congress.

September 19, 2017: FBI interviews Sater. Cohen attempts to preempt an interview with SSCI by releasing a partial statement before testifying, only to have SSCI balk and reschedule the interview.

October 4, 2017: Additional SAR restricted because of ongoing sensitive investigations.

October 20, 2017: Cohen included in expanded scope of investigation.

October 24, 2017: HPSCI interviews Cohen.

October 25, 2017: SSCI interviews Cohen.

November 7, 2017: Mueller extends PR/TT on Cohen Gmail.

November 13, 2017: FBI obtains Cohen’s Gmail going back to June 1, 2015 and his 1&1 email. Adds wire fraud. ¶14-20 redacted.¶23a-25 adds Taxi medallion liability. Eliminates Ukraine/sanctions plan in unredacted section. Adds section F, payments in connection with political activities (associated with AT&T, expand Novartis, add Michael D Cohen and Associates.

December 15, 2017: FBI interviews Sater.

January 4, 2018: Mueller extends PR/TT on Cohen Gmail.

February 8, 2018: Mueller provides SDNY with Gmail and 1&1 email returns.

February 16, 2018: SDNY obtains d-order for header information on 1&1 account.

February 28, 2018: SDNY obtains warrant for emails sent after November 14, 2017 and warrant for emails Mueller handed over in conjunction with different conspiracy, false statements to a bank, wire fraud, and and bank fraud charges.

March 7, 2018: Mueller provides SDNY with iCloud returns.

March 15, 2018: Press reports that Mueller subpoenaed Trump Organization.

April 5, 2018: After CLOUD Act passes, SDNY applies for Google content that had been stored overseas and withheld in February 28 warrant.

April 7, 2018: FBI obtains warrant for cell location for two cell phones, tied only to illegal campaign donation investigation (the FBI would use this to use a triggerfish to identify which room he was in at Loews). FBI obtains warrant to access prior content for use in campaign donation investigation. This is the first warrant that lists 52 USC 30116 and 30109 as crimes being investigated.

April 8, 2018: FBI obtains warrant for cell location for two cell phones, tied only to illegal campaign donation investigation.FBI obtains warrant to search Cohen’s house, office, safe deposit box, hotel room, and two iPhones.

April 9, 2018: FBI obtains a warrant to correct Cohen’s hotel room.

June 20, 2018: Cohen steps down from RNC position.

July 27, 2018: Sources claim Cohen is willing to testify he was present, with others, when Trump approved of the June 9 meeting with the Russians.

August 7, 2018: First Cohen proffer to Mueller.

August 21, 2018: Cohen pleads guilty to SDNY charges. Warner and Burr publicly note that Cohen’s claim to know about the June 9 meeting ahead of time conflicts with his testimony to the committee.

September 12, 2018: Second proffer.

September 18, 2018: Third proffer.

October 8, 2018: Fourth proffer.

October 17, 2018: Fifth proffer.

November 12, 2018: Sixth proffer.

November 20, 2018: Seventh proffer.

November 29, 2018: Cohen pleads guilty to false statements charge.

As I disclosed last July, I provided information to the FBI on issues related to the Mueller investigation, so I’m going to include disclosure statements on Mueller investigation posts from here on out. I will include the disclosure whether or not the stuff I shared with the FBI pertains to the subject of the post.

![[Photo: National Security Agency, Ft. Meade, MD via Wikimedia]](https://www.emptywheel.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/NationalSecurityAgency_HQ-FortMeadeMD_Wikimedia.jpg)