The NSA’s Retroactive Discovery of Tamerlan Tsarnaev

In the days after the Boston Marathon attack last year, NSA made some noise about expanding its domestic surveillance so as to prevent a similar attack.

But in recent days, we’ve gotten a lot of hints that NSA may have just missed Tamerlan Tsarnaev.

Consider the following data points.

First, in a hearing on Wednesday, Intelligence Community Inspector General Charles McCullough suggested that the forensic evidence found after the bombing might have alerted authorities to Tamerlan Tsarnaev’s radicalization.

Senator Tom Carper: If the Russians had not shared their initial tip, would we have had any way to detect Tamerlan’s radicalization?

[McCullough looks lost.]

Carper: If they had not shared their original tip to us, would we have had any way to have detected Tamerlan’s radicalization? What I’m getting at here is just homegrown terrorists and our ability to ferret them out, to understand what’s going on if someone’s being radicalized and what its implications might be for us.

McCullough: Well, the Bureau’s actions stemmed from the memo from the FSB, so that led to everything else in this chain of events here. You’re saying if that memo didn’t exist, would he have turned up some other way? I don’t know. I think, in the classified session, we can talk about some of the post-bombing forensics. What was found, and that sort of thing. And you can see when that radicalization was happening. So I would think that this would have come up, yes, at some point, it would have presented itself to law enforcement and the intelligence community. Possibly not as early as the FSB memo. It didn’t. But I think it would have come up at some point noting what we found post-bombing.

Earlier in the hearing (around 11:50), McCullough described reviewing evidence “that was within the US government’s reach before the bombing, but had not been obtained, accessed, or reviewed until after the bombing” as part of the IG Report on the attack. So some of this evidence was already in government hands (or accessible to it as, for example, GCHQ data might be).

We know some of this evidence not accessed until after the bombing was at NSA, because the IG Report says so. (See page 20)

That may or may not be the same as the jihadist material Tamerlan posted to YouTube in 2012, which some agency claims could have been identified as Tamerlan even though he used a pseudonym for some of the time he had the account.

The FBI’s analysis was based in part on other government agency information showing that Tsarnaev created a YouTube account on August 17, 2012, and began posting the first of several jihadi-themed videos in approximately October 2012. The FBI’s analysis was based in part on open source research and analysis conducted by other U.S. government agencies shortly after the bombings showing that Tsarnaev’s YouTube account was created with the profile name “Tamerlan Tsarnaev.” After reviewing a draft of this report, the FBI commented that Tsarnaev’s YouTube display name changed from “muazseyfullah” to “Tamerlan Tsarnaev” on or about February 12, 2013, and suggested that therefore Tsarnaev’s YouTube account could not be located using the search term “Tamerlan Tsarnaaev” before that date.20 The DOJ OIG concluded that because another government agency was able to locate Tsarnaev’s YouTube account through open source research shortly after the bombings, the FBI likely would have been able to locate this information through open source research between February 12 and April 15, 2013. The DOJ OIG could not determine whether open source queries prior to that date would have revealed Tsarnaev to be the individual who posted this material.

20 In response to a DOJ OIG request for information supporting this statement, the FBI produced a heavily redacted 3-page excerpt from an unclassified March 19, 2014, EC analyzing information that included information about Tsarnaev’s YouTube account. The unredacted portion of the EC stated that YouTube e-mail messages sent to Tsarnaev’s Google e-mail account were addressed to “muazseyfullah” prior to February 12, 2013, and to “Tamerlan Tsarnaev” beginning on February 14, 2013. The FBI redacted other information in the EC about Tsarnaev’s YouTube and Google e-mail accounts.

The FBI may not have been able to connect “muazseyfullah” with Tamerlan, but that’s precisely what the NSA does with its correlations process; it has a database that does just that (though it’s unclear whether it would have collected this information, especially given that it postdated the domestic Internet dragnet being shut down).

Finally, there’s the matter of the Anwar al-Awlaki propaganda.

An FBI analysis of electronic media showed that the computers used by Tsarnaev contained a substantial amount of jihadist articles and videos, including material written by or associated with U.S.-born radical Islamic cleric Anwar al-Aulaqi. On one such computer, the FBI found at least seven issues of Inspire, an on-line English language magazine created by al-Aulaqi. One issue of this magazine contained an article entitled, “Make a Bomb in the Kitchen of your Mom,” which included instructions for building the explosive devices used in the Boston Marathon bombings.

Information learned through the exploitation of the Tsarnaev’s computers was obtained through a method that may only be used in the course of a full investigation, which the FBI did not open until after the bombings.

The FBI claims they could only find the stuff on Tamerlan’s computer using methods available in full investigations (this makes me wonder whether the FBI uses FISA physical search warrants to remotely search computer hard drives).

But that says nothing about what NSA (or even FBI, back in the day when they had the full time tap on Awlaki, though it’s unclear what kind of monitoring of his content they’ve done since the government killed him) might have gotten via a range of means, including, potentially, upstream searches on the encryption code for Inspire.

In other words, there’s good reason to believe — and the IC IG seems to claim — that the government had the evidence to know that Tamerlan was engaging in a bunch of reprehensible speech before he attacked the Boston Marathon, but they may not have reviewed it.

Let me be clear: it’s one thing to know a young man is engaging in reprehensible but purportedly protected speech, and another to know he’s going to attack a sporting event.

Except that this purportedly protected speech is precisely — almost exactly — the kind of behavior that has led FBI to sic multiple informants and/or undercover officers on other young men, including Adel Daoud and Mohamed Osman Mohamud, even in the absence of a warning from a foreign government.

And they didn’t here.

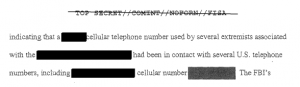

Part of the issue likely stems from communication failures between FBI and NSA. The IG report notes that “the relationship between the FBI and the NSA” was one of the most relevant relationships for this investigation. Did FBI (and CIA) never tell the NSA of the Russian warning? And clearly they never told NSA of his travel to Russia.

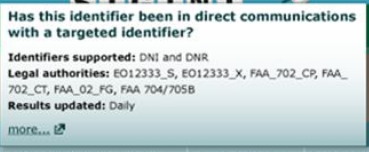

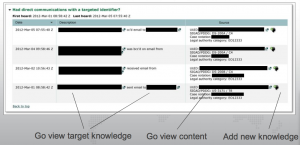

But part of the problem likely stems from the way NSA identifies leads — precisely the triaging process I examined here. That is, NSA is going to do more analysis on someone who communicates with people who are already targeted. Obviously, the ghost of Anwar al-Awlaki is one of the people targeted (though the numbers of young men who have Awlaki’s propaganda is likely huge, making that a rather weak identifier). The more interesting potential target would be William Plotnikov, the Canadian-Russian boxer turned extremist whom Tamerlan allegedly contacted in 2012 (and it may be this communication attempt is what NSA had in its possession but did not access until after the attacks). But I do wonder whether the NSA didn’t prioritize similar targets in countries of greater focus, like Yemen and Somalia.

It’d be nice to know the answer to these questions. It ought to be a central part of the debate over the NSA and its efficacy or lack thereof. But remember, in this case, the NSA was specifically scoped out of the heightened review (as happened after 9/11, which ended up hiding the good deal of warning the NSA had before the attack).

We’ve got a system that triggers on precisely the same kind of speech that Tamerlan Tsarnaev engaged in before he attacked the Marathon. But it didn’t trigger here.

Why not?