Shaping Traffic and Spying on Americans

At the Intercept earlier this week, Peter Maass described an interview he had with a former NSA hacker he calls Lamb of God — this is the guy who did the presentation boasting “I hunt SysAdmins.” On the interview, I agree with Bruce Schneier that it would have been nice to hear more from Lamb of God’s side of things.

At the Intercept earlier this week, Peter Maass described an interview he had with a former NSA hacker he calls Lamb of God — this is the guy who did the presentation boasting “I hunt SysAdmins.” On the interview, I agree with Bruce Schneier that it would have been nice to hear more from Lamb of God’s side of things.

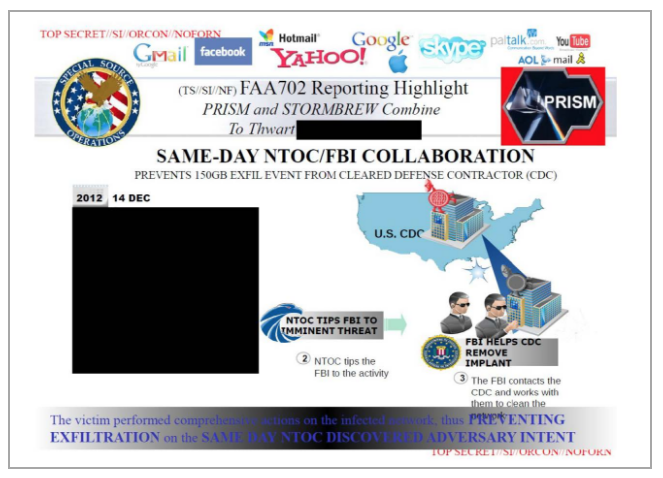

But the Intercept posted a number of documents that should have been posted long, long ago, covering how the NSA “shapes” Internet traffic and how it identifies those using Tor and other anonymizers.

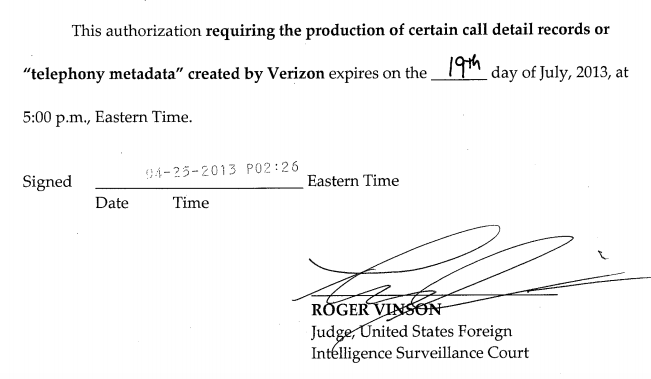

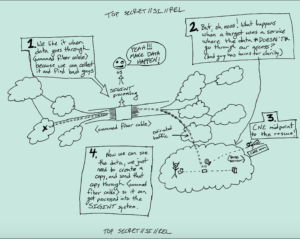

I’m particularly interested in the presentations on shaping traffic — which is summarized in the hand-written document to the right and laid out in more detail in this presentation.

Both describe how the NSA will force Internet traffic to cross switches where it has collection capabilities. We’ve known they do this. Beyond just the logic of it, some descriptions of NSA’s hacking include descriptions of tracking traffic to places where a particular account can be hacked.

But the acknowledgement that they do this and discussions of how they do so is worth closer attention.

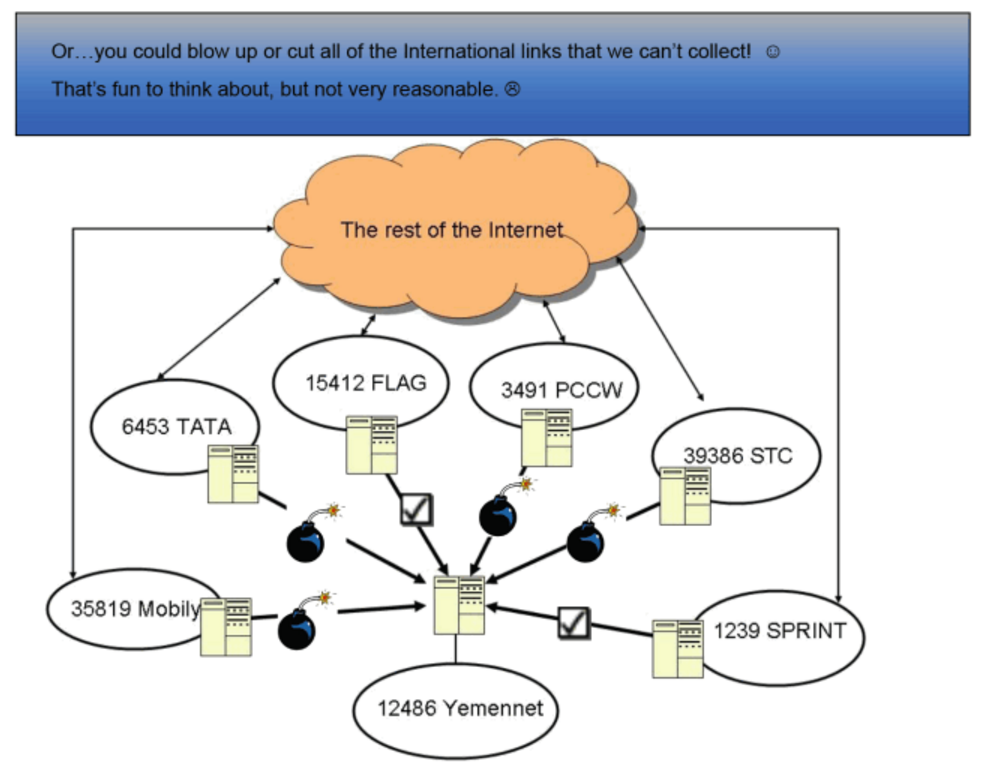

That’s true, first of all, because of wider discussions of cable maps. In discussing the various ways to make Internet traffic cross switches to which the NSA has access, Lamb of God facetiously (as is his style) suggests you could bomb or cut all the cable lines that feed links to which the NSA doesn’t have access.

Lamb of God dismisses this possibility as “fun to think about, but not very reasonable.”

But we know that cable lines do get cut. Back in 2008, for example, there were a slew of cables coming into the Middle East that got cut at one time (though that may have been designed to cut Internet communication more generally). Then there’s the time in 2012 when NSA tried to insert an exploit into a Syrian route, only to knock out almost all of the country’s Internet traffic.

One day an intelligence officer told him that TAO—a division of NSA hackers—had attempted in 2012 to remotely install an exploit in one of the core routers at a major Internet service provider in Syria, which was in the midst of a prolonged civil war. This would have given the NSA access to email and other Internet traffic from much of the country. But something went wrong, and the router was bricked instead—rendered totally inoperable. The failure of this router caused Syria to suddenly lose all connection to the Internet—although the public didn’t know that the US government was responsible. (This is the first time the claim has been revealed.)

Inside the TAO operations center, the panicked government hackers had what Snowden calls an “oh shit” moment. They raced to remotely repair the router, desperate to cover their tracks and prevent the Syrians from discovering the sophisticated infiltration software used to access the network. But because the router was bricked, they were powerless to fix the problem.

Fortunately for the NSA, the Syrians were apparently more focused on restoring the nation’s Internet than on tracking down the cause of the outage. Back at TAO’s operations center, the tension was broken with a joke that contained more than a little truth: “If we get caught, we can always point the finger at Israel.”

Again, we’ve known this happened, which is why it would have been nice to have this presentation three years ago, if only to explain the concept to those who don’t factor it into considerations of how the NSA works.

The other reason this is important is because of the possibility the NSA could deliberately shape traffic to take it out of FISA-controlled domestic space and into EO 12333-governed international space, a possibility envisioned in a 2015 paper. The slides from the paper present the same techniques laid out in the NSA presentation as hypothetical. And, as their more accessible write up explains, the NSA’s denials about this practice don’t actually address their underlying argument, which is that 1) the technology would make this easy, 2) the legal regime is outdated and thereby tolerates such loopholes, and 3) the parts of declassified versions of USSID-18 that might address it are all redacted.

In the paper, we reveal known and new legal and technical loopholes that enable internet traffic shaping by intelligence authorities to circumvent constitutional safeguards for Americans. The paper is in some ways a classic exercise in threat modeling, but what’s rather new is our combination of descriptive legal analysis with methods from computer science. Thus, we’re able to identify interdependent legal and technical loopholes, mostly in internet routing. We’ll definitely be pursuing similar projects in the future and hope we get other folks to adopt such multidisciplinary methods too.

As to the media coverage, the CBS News piece contains some outstanding reporting and an official NSA statement that seeks – but fails – to debunk our analysis:

However, an NSA spokesperson denied that either EO 12333 or USSID 18 “authorizes targeting of U.S. persons for electronic surveillance by routing their communications outside of the U.S.,” in an emailed statement to CBS News.

“Absent limited exception (for example, in an emergency), the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act requires that we get a court order to target any U.S. person anywhere in the world for electronic surveillance. In order to get such an order, we have to establish, to the satisfaction of a federal judge, probable cause to believe that the U.S. person is an agent of a foreign power,” the spokesperson said.

The NSA statement sidetracks our analysis by re-framing the issue to construct a legal situation that conveniently evades the main argument of our paper. Notice how the NSA concentrates on the legality of targeting U.S. persons, while we argue that these loopholes exist when i) surveillance is conducted abroad and ii) when the authorities do not “intentionally target a U.S. person.” The NSA statement, however, only talks about situations in which U.S. persons are “targeted” in the legal sense.

As we describe at length in our paper, there are several situations in which authorities don’t intentionally target a U.S. person according to the legal definition, but the internet traffic of many Americans can in fact be affected.

Once you’re collecting in bulk overseas, you have access to US person communications with a far lower bar than you do under the FISA regime (which is what John Napier Tye strongly suggested he had seen).

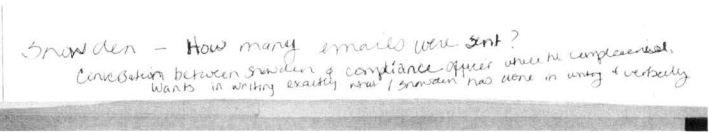

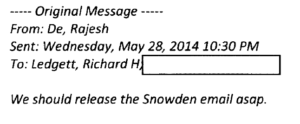

This is one of the reasons I think the NSA’s decision not to answer obvious questions about where FISA ends and EO 12333 begins, in the context of concerns Snowden raised at precisely the time he was learning about this traffic shaping, to be very newsworthy. Using traffic shaping to access US person content even if it’s only in bulk (in the same way that hacking Google cables overseas) clearly bypasses the FISA regime. We don’t know that they do this intentionally for US traffic. But we do know it would be technically trivial for the NSA to pull off, and we do know that multiple NSA documents make it clear they were playing in that gray area at least until 2013 (and probably 2014, when Tye came forward).

The traffic shaping paper ultimately tries to point out how our legal regime fails to account for obvious technical possibilities, technical possibilities we know NSA exploits, at least overseas. Particularly as ODNI threatens to permit the sharing EO 12333 data more broadly — along with access to back door searches — this possibility needs to be more broadly discussed.