Daniel Hale, Citizenfive

Jeremy Scahill: So if I have a confidential source who’s giving me information as a whistleblower and he works within the US government and he’s concerned about what he perceives as violations of the Constitution, and he gets in touch with me…

Bill Binney: From there on they would nail him and start watching everything he did, and if he started passing data, I’m sure they’d take him off the street. I mean, the way you have to do it is like Deep Throat did in the Nixon years — meet in the basement of a parking garage. Physically.

— Citizenfour

Last week, drone whistleblower Daniel Hale pled guilty. In pleading guilty, Hale admitted that he was the source behind The Intercept‘s Drone Papers package of stories that provided new details about the drone program as operated under President Obama. He also may have made clear that Laura Poitras’ film, Citizenfour, isn’t so much about Snowden, as it has always been described, but about Hale.

Hale pled guilty to one of five counts against him, Count 2 of the superseding indictment, 18 USC §793(e), for retaining and transmitting National Defense Information to Jeremy Scahill (Scahill was referred to as “the Reporter” in charging documents).

Before Hale pled guilty, the government released a list of exhibits it planned to use at trial. The exhibit list not only shows the government would have introduced a picture of Hale meeting publicly with Scahill at an event for the latter’s Dirty Wars, texts Hale sent to his friend Megan describing meeting Scahill, emails between Scahill and Hale sent months before they moved their communication to Jabber (those all were mentioned in the Indictment), but it included texts Hale and Scahill exchanged between January 24 and March 7, 2014, continuing after Hale had started the process of printing off documents at the contractor where he worked which he would ultimately send to Scahill. (The exhibit list doesn’t describe via what means they sent these texts and there are no correlating Verizon records prepared as exhibits covering that period, meaning they may not be telephony texts but instead could be the Jabber chats mentioned in the indictment, or maybe Signal texts). The government also would have introduced up to seven types of proof that Hale had printed each of the documents he was charged with, and badge records showing he was in his office and logged onto the relevant work computer each time those documents were printed out.

The government would also have submitted, for each of the agencies where Hale ever held clearance — NSA, DOD, a JSOC Task Force, NGA, and Air Force — a certification that the agency had no evidence that Hale had made any whistleblower complaints.

Unless those 2014 texts were from Jabber, there’s nothing in the exhibit list that obviously shows that the government was intending to introduce proof of three Jabber chats the government reconstructed that Hale had with Scahill, though those were mentioned in the indictment.

At the change of plea hearing last Thursday, the government refused to dismiss the four other counts against Hale, which Hale’s attorney, Todd Richman, said raised concerns that the government might revert to those charges if Judge Liam O’Grady didn’t sentence Hale harshly enough. O’Grady (who seemed as concerned about the possibility Hale might harm himself between now and the July 13 sentencing as anything else) as much as said that, if the government tried that, it would still amount to the same sentence, signaling he would have sentenced Hale with a concurrent sentence for all counts, had he gone to trial.

The plea agreement has not been released yet, but pleading guilty days before the trial was to start will give Hale a slight reduction in his sentence, but he’s still facing a draconian sentence for revealing details about the drone program.

That said, given what EDVA prosecutors — including Hale prosecutor Gordon Kromberg, who is the lead prosecutor on the Assange case — did to Chelsea Manning and Jeremy Hammond, I worry they might try something similar with Hale. From the start, the government has been interested in Hale for how he fit in the series of document leaks that started with Chelsea Manning and continued through Vault 7. That came up in mostly sealed filings submitted early in Hale’s prosecution.

[T]he FBI repeatedly characterized its investigation in this case as an attempt to identify leakers who had been “inspired” by a specific individual – one whose activity was designed to criticize the government by shedding light on perceived illegalities on the part of the Intelligence Community.

And the government intended to submit exchanges between Hale and Scahill about Snowden and Chelsea Manning at trial.

There are two things that appear in the Statement of Facts Hale pled guilty to that don’t appear in the indictment.

First, the biographical language that explains how Hale enlisted in the Air Force, quit in May 2013, and only then got a job at a defense contractor where he had access to the files he ultimately leaked, is slightly different and generally abbreviated (leaving out, for example, that Hale was assigned to the NSA from 2011 to 2013, overlapping with Snowden). However, the Statement of Facts adds the detail that, “In July 2009, while the United States was actively engaged in two wars,” Hale first enlisted. It’s as if to suggest that Hale knew he would end up killing people when he signed up to join the Air Force.

Of more interest, the Statement of Facts includes an admission that Hale authored an anonymous document that prosecutors had planned to use at trial.

Mr. Hale authored an essay, attributed to “Anonymous,” that became a chapter in a book published by the Reporter’s online news outlet (defined as Book 2 in the Superseding Indictment).

It’s a chapter in The Assassination Complex, a free-standing publication based on the documents Hale released.

The government first requested to use this document at trial in a sealed motion, accompanied by 6 exhibits, submitted on September 16, 2019 as part of the first wave of motions. But the judge didn’t resolve that request until November 17, 2020, a month after a hearing on that and other requests. In his order, O’Grady permitted the government to enter the chapter into evidence, but reminded them the jury gets to decide whether they believe the evidence is authentic or not.

The Court hereby ORDERS that the Government’s Motion to Admit an Anonymous Writing as an Admission of the Defendant (dkt. 54) is GRANTED, as the Court stated in the October 13 hearing; the government will be permitted to present the book chapter attributed to an anonymous author. Federal Rule of Evidence 901(a) requires the proponent of a piece of evidence to authenticate it before it can be admitted. United States v. Smith, 918 F.2d 1501,1510 (11th Cir. 1990). The Court’s role in determining whether evidence is authentic is limited to that of a gatekeeper in assessing whether the proponent has offered a satisfactory foundation.” United States v. Vidacak, 553, F.3rd 344, 349 (4th Cir. 2009). The court finds that the government has laid satisfactory foundation for the purpose of admitting the evidence at trial. It now falls to the jury to determine whether the evidence is indeed what the government says it is: an anonymous writing that was written by Defendant admitting to the conduct of which he is accused.

At trial, it seems, the government would have treated this chapter as a confession. There are three exhibits in their trial exhibit list — stills and video of an Obama event in June 2008 — that suggest they planned to authenticate it, in part, by pointing to the anonymous author’s admission that he shook then-Candidate Obama’s hand in 2008 and showing pictures of the exchange.

In 2008 I shook hands with Senator Obama when he came through my town on his way to the White House. After his inauguration he said, “Transparency and the rule of law will be the touchstones of this presidency.” I firmly believe those principles are crucial to an open society, which is why I was compelled to reveal this information. If this administration lacks the courage to uphold its promises to the people, then I and others like me will do so for them.

So after having made their case that this was Hale, they then would have asked the jury to consider it a confession that he was the leaker described throughout The Intercept‘s reporting on the drones.

But with Hale’s guilty plea, there’s no evidentiary value to this chapter anymore. (That is, unless the government wants to argue that the specific Tide Personal Numbers Hale listed in the chapter — TPN 1063599 for Osama bin Laden and TPN 26350617 for Abdul Rahman al-Awlaki — amount to new disclosures not included in the charged releases.) Hale has already admitted, under oath, to being the anonymous source referred to by journalists throughout the rest of the book.

What the admission that he was part of the book publication does do, however, is tie Hale far more closely with Snowden, who wrote a hubristic introduction for the book. In it, he tied his leaks with Manning’s and in turn his with Hale’s.

[U]nlike Dan Ellsberg, I didn’t have to wait forty years to witness other citizens breaking that silence with documents. Ellsberg gave the Pentagon Papers to the New York Times and other newspapers in 1971; Chelsea Manning provided the Iraq and Afghan War logs and the Cablegate materials to WikiLeaks in 2010. I came forward in 2013. Now here we are in 2015, and another person of courage and conscience has made available the set of extraordinary documents that are published here.

I noted, when Snowden called for Trump to pardon Hale along with The Intercept‘s other sources, Terry Albury and Reality Winner, he effectively put a target on Hale’s back, because it suggested those leaks all tied to him. All the more so, I now realize, given the way this Snowden essay suggests Hale’s leaks have some tie to him.

Snowden ended the introduction by suggesting there were far more people like Manning, himself, and Hale waiting to drop huge amounts of documents than there were the “insiders at the highest levels of government” guarding the monopoly on violence.

The individuals who make these disclosures feel so strongly about what they have seen that they’re willing to risk their lives and their freedom. They know that we, the people, are ultimately the strongest and most reliable check on the power of government. The insiders at the highest levels of government have extraordinary capability, extraordinary resources, tremendous access to influence, and a monopoly on violence, but in the final calculus there is but one figure that matters: the individual citizen.

And there are more of us than there are of them.

Yet the book suggests the links between Manning, Snowden, and Hale are merely inspirational.

Not so Citizenfour.

There’s a scene of the movie, quoted above, where Bill Binney warns Jeremy Scahill that if he wanted to publish documents from a source we now know to be Hale, with whom (trial exhibits would have shown) Scahill had already met in public, emailed, and texted during the period Hale was leaking, then (Binney instructed Scahill) he needed to do so by meeting in person, secretly.

It was probably too late for Hale by the time Binney gave Scahill this warning.

Then there’s the film’s widely discussed closing scene, showing a meeting where Glenn Greenwald flew to Moscow to update Snowden about “the new source” that has come to The Intercept. Apparently believing he’s using rockstar operational security, he’s writing down — on camera!!! — how The Intercept is communicating with this new source, bragging (still writing on camera about a source that had first reached out to Scahill via email and in person) that “they’re very careful.” One of the things he seems to write down is “Jabber,” chats from which the government obtained and might have released at Hale’s trial. In the scene, Greenwald continues to sketch out the contents of several of the documents — including one of the first ones to be published — that Hale just admitted he shared with The Intercept.

But in retrospect, the most important part of this sequence is where — against video footage showing Snowden and Lindsey in Moscow together — Poitras reads an email, dated April 2013 (a month before Hale quit the Air Force and NSA within days after Snowden fled to Hong Kong). She offers no explanation, not even naming the recipient of the email.

Let’s disassociate our metadata one last time, so we don’t have a clear record of your true name and our final communication chain. This is obviously not to say you can’t claim your involvement. But as every trick in the book is likely to be used in looking into this, I believe it’s better that that particular disclosure come on your own terms. Thank you again for all you’ve done. So sorry again for the multiple delays but we’ve been in unchartered territory with no model to benefit from. If all ends well, perhaps the demonstration that our methods worked will embolden more to come forward.

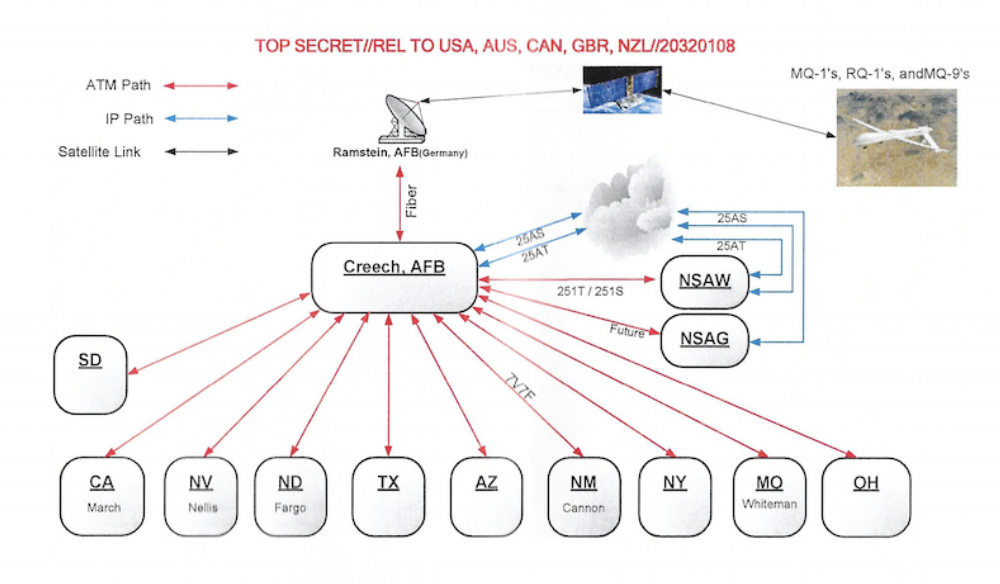

That email has received far less attention than Greenwald’s confident descriptions to Snowden of how someone inspired by his actions has come forward. But I remember when first viewing Citizenfour (which I watched long after it first came out), I had the feeling that Snowden was only feigning surprise when Greenwald told him of this new source and described the signals intercepts for the drone program going through Ramstein Air Base in Germany.

That is, that unexplained email may suggest that Hale met Snowden while both were at the NSA, and that days before the first Snowden releases, Hale quit, reached out to a close associate of Greenwald, then (months later) found a new job in the intelligence community where he could get files that would expose certain details of the drone program. The government had planned to introduce other movies at Hale’s trial. But Citizenfour was not on the exhibit list.

Update: PseudonymousInDenver has persuaded me this is a reference to Poitras, not to someone else.

That’s a detail I hadn’t realized before: Hale reached out to Scahill, then quit the Air Force and NSA, and only then got a new job that gave him access to files he ended up leaking.

I have no idea what the government intends to do, now that it has Hale admitting that he participated in this book in which Snowden promised a legion of similar leakers. I have always been concerned the government would go after Scahill. But now I think this is about Snowden.

Since last year, the government has explicitly argued that WikiLeaks considered its help to Snowden as part of a recruiting effort for further leakers (a detail of Julian Assange’s most recent superseding indictment that literally every one of Snowden’s closest associates has studiously avoided mentioning). They’re not making that up. It’s something Snowden admitted in his own book, and Bart Gellman described that Snowden was thinking the same as he leaked to Gellman. As noted, the government appears to have made a similar argument in sealed filings with Hale.

But one thing they seem to have demanded before they let Hale plead out before trial was a further admission, one that makes the Snowden tie more explicit.

Update: On Twitter, Hale corrected me that that TPN is for Awlaki’s son, not for Awlaki himself.