Who Will Redact Our Next Big Constitutional Debate?

In her Gitmo anniversary piece, Dahlia Lithwick, piggybacking on Adam Liptak’s earlier report, used the extensive redactions in the DC Circuit Opinion overturning Adnan Latif’s habeas petition to illustrate how little the courts are telling us about his fate, our detention program, and its impact on the most basic right in this country, habeas corpus.

In her Gitmo anniversary piece, Dahlia Lithwick, piggybacking on Adam Liptak’s earlier report, used the extensive redactions in the DC Circuit Opinion overturning Adnan Latif’s habeas petition to illustrate how little the courts are telling us about his fate, our detention program, and its impact on the most basic right in this country, habeas corpus.

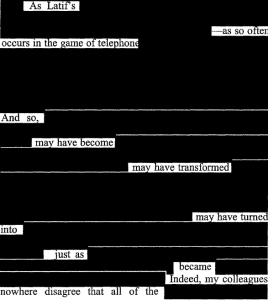

But in the spirit of the day, I urge you to stop for a moment and look at the decision itself, so heavily redacted that page after page is blacked out completely. The court, in evaluating a secret report on Latif, can tell us very little about the report and thus the whole opinion becomes an exercise in advanced Kafka: The dissent, for instance notes that “As this court acknowledges, “the [district] court cited problems with the report itself including [REDACTED]. … And according to the report there is too high a [REDACTED] in the report for it to have resulted from [REDACTED].” Liptak describes all this as an exercise in “Mad Libs, Gitmo Edition.” But in the end, it’s also an exercise in turning the legal process of assessing the claims of these prisoners at Guantanamo Bay into something that replaces one legal black hole with another: pages and pages of black lines that obscure in words what has been obscured in fact. Americans will never know or care what was done at the camp and why if the legal process that might have transparently corrected errors happens behind blacked-out pages.

Latif’s classified petition for cert has just been filed.

We won’t get to see that petition, though, until after the court redacts it, at which point it will presumably look just like the Circuit Opinion–page after page of black lines.

It’s worth asking who will get to redact that petition, which is after all an important effort not only to free a man cleared for release years ago, but also to restore separation of powers and prevent detainees and Americans alike from being held solely on the basis of an inaccurate intelligence report.

That’s important because, thus far, the existing court documents in this case have been redacted inconsistently.

We know that because the dissent in the Circuit Opinion quotes language from Judge Henry Kennedy’s ruling, yet that language doesn’t appear anywhere in the unredacted sections of his ruling itself. For example, David Tatel refers to the “factual errors” Kennedy described (21; PDF 88) and cites Kennedy’s repetition of Latif’s explanation for having lost his passport–he “gave it to Ibrahim [Alawi] to use in arranging his stay at a hospital.” (37; PDF 104) Yet the appearances of these phrases have been entirely redacted from Kennedy’s opinion (there are many more fragments for which the same is true, supporting general claims about the inaccuracy of the report, but they are less specific).