Latif’s Death: A Blow to the Head of Our System of Justice

I’d like to take issue with Ben Wittes’ post on the sadness of Adnan Farhan abd al Latif’s death. I certainly agree with Wittes that Latif’s death is terribly sad. But I object to Wittes’ take on three related grounds. Wittes,

I’d like to take issue with Ben Wittes’ post on the sadness of Adnan Farhan abd al Latif’s death. I certainly agree with Wittes that Latif’s death is terribly sad. But I object to Wittes’ take on three related grounds. Wittes,

- Provides a problematic depiction of the justification for Latif’s detention

- Misstates the importance of Latif’s clearance for release

- Assigns responsibility for Latif’s continued detention to the wrong people

Wittes tries hard to downplay how much Latif’s death in custody damns Gitmo. But he does so by obscuring a number of key facts all while accusing Gitmo foes of building up “myths.”

A problematic depiction of the justification for Latif’s detention

Before he talks about how sad this is, Wittes tries to refute the “myths” Gitmo opponents have spread. First, he argues, we should not be arguing Latif was innocent.

Guantanamo’s foes are building up a lot of myths about the Latif case—many of which I don’t buy at all. While I have criticized the D.C. Circuit’s opinion in the case, it does not follow from the decision’s flaws that Latif was an innocent man wrongly locked up for more than a decade. Indeed, as I argued inthis post, it is possible both that the district court misread the evidence as an original matter and that the D.C. Circuit overstepped itself in reversing that decision. The evidence in the case—at least what we can see of it—does not suggest to me that Latif had no meaningful connection to enemy forces. [my emphasis]

After twice using the squirreliest of language, Wittes finally settles on a lukewarm endorsement of the argument that Latif had some “meaningful connection” to the enemy. Curiously, though, he exhibits no such hesitation when he describes Latif this way:

Latif—a guy whose mental state was fragile, who had suffered a head injury, and who seems to have had a long history of self-injury and suicide attempts. [my emphasis]

That’s curious because whether or not Latif continued to suffer from his 1994 head injury was a central issue in whether or not Latif was credible and therefore whether he should be released. Moreover, it is one area where–as I explained in this post–Janice Rogers Brown fixed the deeply flawed argument the government made, thereby inventing a new (equally problematic, IMO) argument the government had not even plead to uphold the presumption of regularity that has probably closed off habeas for just about all other Gitmo detainees.

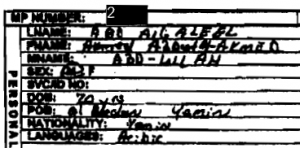

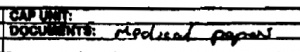

As you’ll recall, Henry Kennedy found Latif’s argument he had traveled to Afghanistan for medical treatment for his head injury credible because DOD’s own intake form said he had medical records with him when they took custody of him in Kandahar.

Furthermore, there are indications in the record that when Latif was seized traveling from Afghanistan to Pakistan, he was in possession of medical records. JE 46 at 1 (noting that Latif was seized in a “[b]order [t]own in [Pakistan]” with “medical papers”); JE 66 (unidentified government document compiling information about Latif) at 2 (stating that “[Latif] had medical papers but no passport or weapon” when he “surrendered himself to [Pakistani] authorities”).12

David Tatel, too, pointed to that in his dissent: “the most plausible reason for why Latif would have had medical papers in his possession when first seized is that his trip in fact had a medical purpose.”

Yet the government argued that Latif offered no corroboration for his story.

The court improperly gave no adverse weight to the conclusory nature of Latifs declaration, and the lack of corroboration for his account of his trip to Afghanistan, both factors which should have weighed heavily against his credibility.

[snip]

Latif also provided no corroboration for his account of his trip to Afghanistan. He submitted no evidence from a family member, from Ibrahim, or from anyone to corroborate his claim that he was traveling to Pakistan in 2001 to seek medical treatment.

That’s a laughable claim. Latif submitted one of the government’s own documents as corroboration for his story. The government, however–in a brief arguing that all government documents should be entitled to the presumption of regularity–dismissed that corroborating evidence by implying that government document didn’t mean what it said–which is that Latif had medical papers with him when captured.

Respondents argue that these indications are evidence only that Latif said he had medical records with him at the time he was seized rather than that he in fact had them.

The claim is all the more ridiculous given that, unlike the CIA interrogation report the government argued should be entitled to the presumption of regularity, there’s a clear basis for the presumption of regularity of Latif’s intake form: the Army Field Manual. It includes instructions that intake personnel examine documents taken into custody with detainees. They don’t just take detainees’ words for it, they look at the documents.

I’m not suggesting that the government’s claim–that the screener just wrote down whatever Latif said–is impossible; I think it’s very possible. But they can only make that argument if they assume the intake screener deviated from the AFM, and therefore a document created under far more regulated conditions than the CIA report, and one created in US–not Pakistani–custody, should not be entitled to the presumption of regularity. Read more →