How the Government Proved Their Case against John Podesta’s Hacker

We’re almost seven years past the hack of the DNC, and self-imagined contrarians are still clinging to conspiracy theories about the attribution of that and related hacks. In recent weeks, both Matt Taibbi and Jeff Gerth dodged questions about the attribution showing Russia’s role in the hack-and-leak by saying that the Mueller indictment of twelve GRU officers would never be tested in court (even while, especially in Gerth’s case, relying on unsubstantiated claims in John Durham indictments from his two failed prosecutions).

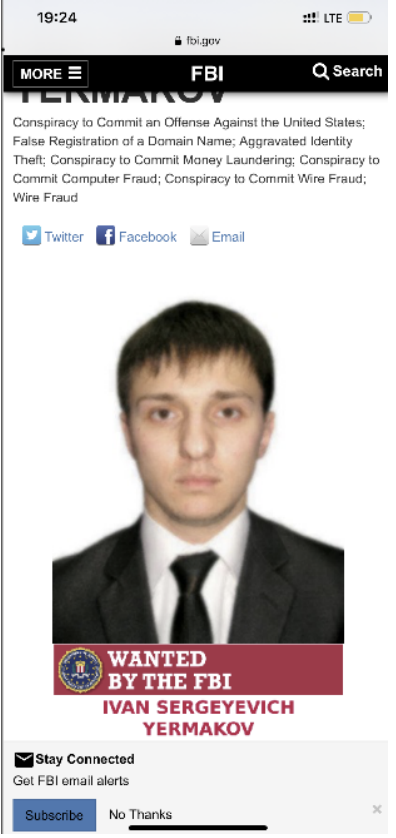

And while’s it’s likely true that DOJ will never extradite any of those twelve men to stand trial, DOJ did successfully convict one of their co-conspirators on a different hack: the hack-and-trade conspiracy involving Vladimir Klyushin and accused John Podesta hacker, Ivan [Y]Ermakov.

(The Mueller indictment and Ermakov’s second US indictment, for hacking anti-doping agencies, transliterated his name with a Y, the Boston one does not.)

That trial provides a way to show how DOJ would prove the 2018 indictment if one of the twelve men charged ever wandered into a jurisdiction with an extradition treaty with the US.

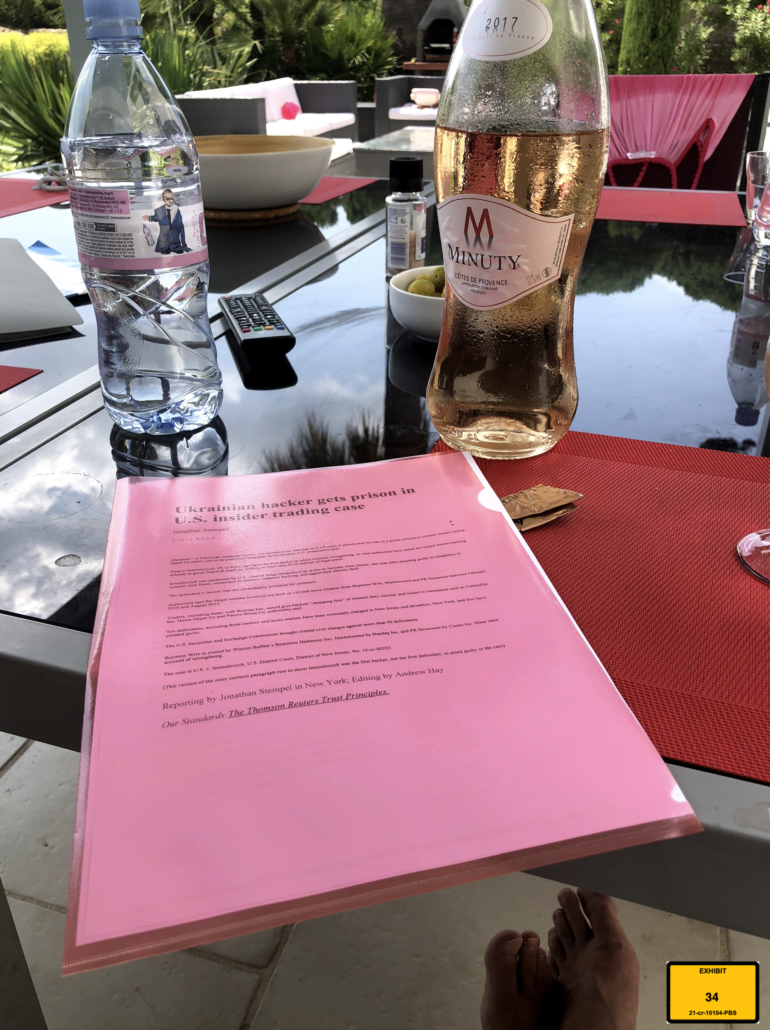

As laid out at trial, between 2018 and 2020, the co-conspirators hacked two securities filing agencies, Toppan Merrill and Donnelly Financial, to obtain earnings statements in advance of their filing, then traded based off advance knowledge of earnings. Klyushin was one of seven people (two charged in a separate indictment, three who were clients of Klyushin’s company M-13) who did the trading. Ermakov didn’t trade under his own name. He may have been compensated for Klyushin’s side of the trades with a Moscow home and a Porsche. But at least as early as May 9, 2018, forensic evidence introduced at trial shows, an IP address at which Ermakov’s iTunes account had just gotten updates was used to steal some of the filings.

Ermakov did not show up in a courtroom in Boston to stand trial and Klyushin has launched a challenge to his conviction that rests entirely on a challenge to venue there. But the jury did convict Klyushin on the hacking charge along with the trading charges, meaning a jury has now found DOJ proved Ermakov’s hacking beyond a reasonable doubt.

And they did it using the same kind of evidence cited in the Mueller indictment.

The crime scene

Start with the crime scene: the servers of the two filing agencies victimized in the hack-and-trade, Toppan Merrill and Donnelly Financial.

According to the trial record, neither figured out they had been hacked on their own. As the FBI had tried to do for months beforehand in the case of the DNC, a government agency, the SEC, had to tell them about it. The SEC had seen a number of Russians making big, improbable stock trades from clients of the two filing agencies, all in the same direction, and wanted to know why. So it sent subpoenas to both companies.

As the DNC did with CrowdStrike in 2016, both filing agencies hired an outside incident response contractor — Kroll Cyber in the case of Toppan Merrill, Ankura in the case of Donnelly Financial — to conduct an investigation.

The lead investigators from those two contractors were the first witnesses at trial. Each explained how they had been brought in in 2019 and described what they found as they began investigating the available logs, which went back six months, a year, and two years, depending on the type and company. The witness from Kroll described finding signs of hacking in Toppan Merrill’s logs:

- A November 28, 2018 use of DirBuster used to brute force file structure on a server

- Evidence of someone renaming PowerShell, RDTEVC, on December 23, 2019 to hide its use

- A December 25, 2019 use of a renamed copy of PuTTY remote access software

- A January 10, 2019 instance of a user invoking MimiKatz

- 8 domains from which intrusions had come with names like “developingcloud” and “finshopland”

- An IP associated with unauthorized activity from an AirVPN address.

The Ankura witness described how they first found the account of employee Julie Soma had been compromised, then used the IP addresses associated with that compromise to find other employees whose accounts were used to download reports or other unauthorized activity.

In sum, the two incident response witnesses described providing the FBI with the forensic details of their investigation — precisely the same thing that CrowdStrike provided to FBI from the DNC hack. There’s not even evidence that they shared a full image of the filing agencies’ servers (though an FBI agent described going back to Donnelly to search for the domain names behind the intrusions that Kroll had found at Toppan Merrill), which was one of the first conspiracy theories about the DNC hack Republicans championed: that the FBI failed to adequately investigate the DNC hack because it didn’t insist on seizing the actual victim servers during the middle of an election.

The forensic evidence wasn’t the only evidence submitted at trial from the crime scene. One after another of the employees whose credentials had been misused testified. Each described why they normally accessed customer records, if at all, how and when they would normally access such records, and from what locations they might access corporate servers remotely, including their use of the corporate VPN. Julie Soma — the Donnelly employee whose credentials were used most often to download customer filings — described that she would never have done what was done in this case, download one after another filing from Donnelly customers in alphabetical order.

Q. Would you ever go from client to client and alphabetically access those types of documents?

A. No.

Both interview records from the Mueller investigation (one, two, three) and documents from the Michael Sussmann case show that the FBI did similar interviews in the DNC hack. The Douglass Mackey trial, too, featured witnesses describing how the Hillary campaign identified that attack on the campaign as well.

In proving their case against John Podesta’s hacker, DOJ presented witness testimony that eliminated insiders as the culprit.

Fingerprinting

Having established the forensic data tied to intruders through the incident response contractors, prosecutors then called FBI agents as witnesses to describe how — largely through the use of IP addresses obtained using subpoenas or pen registers and the materials found in the suspects’ iCloud accounts — they tied Klyushin’s company, M-13, to both the hacking and the trading.

The trading was fairly easy: the co-conspirators accessed the two online brokers used to execute the trades under their own names and from IP addresses tied to M-13. An SEC witness described in detail how trades always shortly followed hacks but preceded the public filing of earnings statements.

Tying M-13 to the hacking took a few more steps.

For the hacking conducted via the domains Kroll identified, the FBI first found the account that registered the domains. Each was registered under a different name, but each of the names were based on a Latvian-based email service and used similar naming conventions. Each had been accessed from the same set of 3 IP addresses.

For IPs that Kroll identified, the FBI found BitLaunch servers created by an account in the name of Andrea Neumann, which was controlled from one of the same IP addresses that had registered the domain names. The FBI got search warrants to obtain images of those BitLaunch servers.

Another IP address used to steal filings, several FBI agents explained, was from an Italian-run VPN, AirVPN. The FBI used a pen register to show that someone accessed AirVPN from the M-13 IP address during the same period when the AirVPN IP was stealing records from the filing companies. The FBI also showed that Klyushin had accessed his bank at the same time from that same IP address. The FBI also showed that eight common IP addresses had accessed Ermakov’s iTunes account and the AirVPN IP address (in this case, the access was not at the same time because the FBI only had a pen register on the VPN for two months in 2020). While FBI witnesses couldn’t show that the specific activity tied to an AirVPN IP at the victim companies tied back to M-13, they did show that both Klyushin and Ermakov routinely used AirVPN.

Plus there were the filing thefts — noted above — that were done on May 9, 2018 using the same IP address that, four minutes earlier, had downloaded an Apple update from Ermakov’s iTunes account. As I’ve noted repeatedly, before Ermakov was first indicted by Mueller, he had already left a smoking gun in the servers at Donnelly in the form of IP activity that the FBI obtained over a year later inside the US.

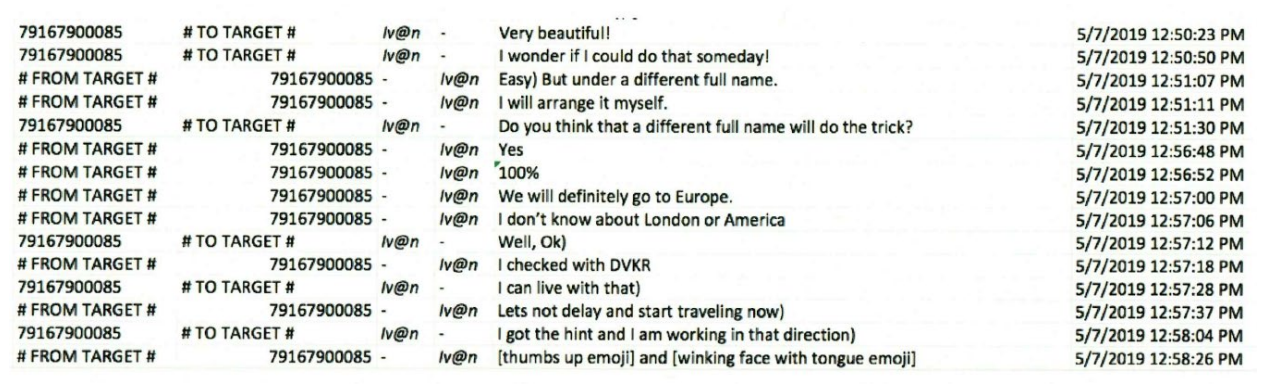

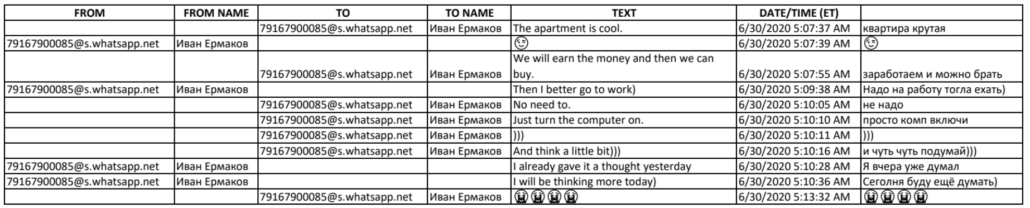

In fact, much of the evidence used to prove this case (particularly establishing the close relationship between the conspirators) came from Apple, including WhatsApp chats saved in Klyushin and other co-conspirators’ iCloud accounts. We know Mueller used the same source of evidence. In March of this year, emails stolen by hacktivists revealed, Apple informed another of the GRU officers charged in the DNC hack that the FBI had obtained material from his Apple account in April 2018, in advance of the Mueller indictment.

The indictment likely also relied on warrants served on Google, especially on Ermakov’s account. The Mueller indictment (as well as the later anti-doping one) attributes much of the reconnaissance conducted in advance of the hacks to Ermakov: the names of some victims; information on the DNC, the Democratic Party, and Hillary; how to use PowerShell (which would be used against Toppan Merrill); and CrowdStrike’s reporting on GRU tools. If he did this research via Google, it would all be accessible with a warrant served on the US tech company.

The getaway car

One pervasive conspiracy theory about the Mueller indictment stems from testimony that Shawn Henry gave to the House Intelligence Committee in December 2017, describing that Crowdstrike did not see the data exfiltrated from the DNC servers. Denialists claim that is proof that the information was never exfiltrated by the GRU hackers. The conspiracy theory is ridiculous in any case, since there were so many other Russian hacks involving so many other servers, including servers run by Google and Amazon that had a different kind of visibility on the hack (something that Henry alluded to in his testimony), and since the indictment describes that the DNC hackers destroyed logs to cover their tracks.

But the Klyushin trial featured testimony about a tool used in the hack-and-trade conspiracy that has a parallel in the DNC hack: the AMS panel, hidden behind an overseas middle server, which the Mueller indictment described this way:

X-Agent malware implanted on the DCCC network transmitted information from the victims’ computers to a GRU-leased server located in Arizona. The Conspirators referred to this server as their “AMS” panel. KOZACHEK, MALYSHEV, and their co-conspirators logged into the AMS panel to use X-Agent’s keylog and screenshot functions in the course of monitoring and surveilling activity on the DCCC computers. The keylog function allowed the Conspirators to capture keystrokes entered by DCCC employees. The screenshot function allowed the Conspirators to take pictures of the DCCC employees’ computer screens.

[snip]

On or about April 19, 2016, KOZACHEK, YERSHOV, and their co-conspirators remotely configured an overseas computer to relay communications between X-Agent malware and the AMS panel and then tested X-Agent’s ability to connect to this computer. The Conspirators referred to this computer as a “middle server.” The middle server acted as a proxy to obscure the connection between malware at the DCCC and the Conspirators’ AMS panel. On or about April 20, 2016, the Conspirators directed X-Agent malware on the DCCC computers to connect to this middle server and receive directions from the Conspirators.

[snip]

For example, on or about April 22, 2016, the Conspirators compressed gigabytes of data from DNC computers, including opposition research. The Conspirators later moved the compressed DNC data using X-Tunnel to a GRU-leased computer located in Illinois.

In the hack-and-trade conspiracy, the hackers set up a similar structure, using the servers given names like “developingcloud” and “finshopland” as reverse proxies, with a final server behind them all executing orders on the hacked servers at Toppan Merrill (and the implication is, Donnelly, though the forensics came from Toppan Merrill via Kroll). The “computers numbered 1 through 7” in what follows are the servers identified by Kroll stealing earnings filings from Toppan Merrill.

A. So this is a digital depiction of the servers that I examined on the right there, so they each have a number on them, 1 through 9.

Q. Let me focus you first on the computers numbered 1 through 7. Do you see them there?

A. Yes.

Q. Are they kind of in a sideways V configuration?

A. Yes.

Q. Okay. And what do computers 1 through 7 show on this Exhibit DDD?

A. They functioned as gatekeepers for the furthest machine to the right, server number 8.

Q. And when you say “gatekeeper,” is there a technical term for that?

A. Yes. So the technical term is a “reverse proxy.”

Q. Can you explain to the jury, in a easy for me to understand way, what a reverse proxy or gatekeeper is in this chart, 1 through 7.

A. Yes. So in this chart, it would function — so the seven that are in that V formation, they would pass traffic to server number 8, if it was coming from an infected machine; and if it was something else, it would send the traffic to some other website.

This structure would have made it impossible for Toppan Merrill to understand the source or function of the anomalous traffic on its servers because any attempt to do so would be redirected away from the control server.

But not the FBI, because they obtained images of the servers with a warrant.

The forensic witness describing this structure showed, command by command, that the forensic clues identified by Kroll on the Toppan Merrill servers were controlled via that final server running PowerShell (the same tool that Mueller alleged Ermakov researched during the DNC hacks in 2016).

Q. And is there something on this log that you found that tells you the name of the program that was running on the victim’s computer at Toppan Merrill?

A. Yes, the process name line, and that reads rdtevc.

Q. And is process another name for computer program?

A. Yes.

Q. So this is a log that shows that a program named RDTEVC was running on a Toppan Merrill computer, right?

A. Yes.

Q. But it’s stored in the hacker computer?

[snip]

Q. And what does PowerShell do? You can call it anything, right? You can call it RDTEVC?

A. That’s probably a randomly chosen name.

Q. But no matter what it’s called, what does it do?

A. So it allows it to be remotely controlled and accessed.

Q. Allows what to be remotely controlled and accessed?

A. The infected machine.

The same forensic expert explained that he didn’t find any downloads of stolen files.

But he also explained why.

He had also found secure tunnels, readily available but similar in function to a proprietary GRU tool Crowdstrike found in the DNC server. As he described, these would be used to transfer data in encrypted form, making it impossible to identify the content of the data while it was in transit.

Q. Mr. Uitto, are you familiar with the concept of exfiltration?

A. Yes.

Q. Big word, but what does it mean?

A. It means to steal data, take data.

Q. And in your review, did you find evidence — you told Mr. Nemtsev you didn’t find evidence of the taking of data from the victim computers to these particular hacker servers; is that right?

A. That’s right, but I did see secure tunnels that were created.

Q. So when you say there were secure tunnels, were you able to tell what was going through those secure tunnels?

A. No.

Q. Those were encrypted, right?

A. Yes.

Q. So you actually don’t know whether or not there was financial information in those tunnels?

A. That’s correct.

Q. Or sports scores or anything?

A. That’s correct.

Q. It’s encrypted.

A. Yes.

[snip]

Q. What role does encryption serve in this hacker architecture?

[snip]

A. Yes, so it can be used to hide data or information.

Q. So if it’s encrypted, we can’t know what’s being passed?

To prove the hack, you would have to — and FBI did, in both cases — prove that the stolen data made it to the end point.

This testimony is important for more than explaining where you’d need to look to find proof of a hack (at the end points). It shows the import of understanding not just the crime scene and those end points, but the infrastructure used to control the hack and exfiltrate the data. With both the hack-and-trade conspiracy and the hack of the DNC, the FBI got forensics about the victim from the incident response contractors, but they obtained the data from these external servers directly, with warrants.

The denialists looking for proof in the DNC server were focused on just the crime scene, but not what I’ve likened to a getaway car, one to which the FBI had direct access but Crowdstrike did not.

Follow the money

Another specialized kind of fingerprint prosecutors used to prove the case against Klyushin parallels the one in the Mueller indictment (and, really, virtually all hacking cases these days): the cryptocurrency trail. As the Mueller indictment explained, the hackers who targeted the DNC used the same cryptocurrency account to pay for different parts of their infrastructure, thereby showing they were all related.

The funds used to pay for the dcleaks.com domain originated from an account at an online cryptocurrency service that the Conspirators also used to fund the lease of a virtual private server registered with the operational email account [email protected]. The dirbinsaabol email account was also used to register the john356gh URL-shortening account used by LUKASHEV to spearphish the Clinton Campaign chairman and other campaign-related individuals.

[snip]

For example, between on or about March 14, 2016 and April 28, 2016, the Conspirators used the same pool of bitcoin funds to purchase a virtual private network (“VPN”) account and to lease a server in Malaysia. In or around June 2016, the Conspirators used the Malaysian server to host the dcleaks.com website. On or about July 6, 2016, the Conspirators used the VPN to log into the @Guccifer_2 Twitter account. The Conspirators opened that VPN account from the same server that was also used to register malicious domains for the hacking of the DCCC and DNC networks.

By following the money, prosecutors were able to show the jury how these pieces of infrastructure fit together.

In the case of the hack-and-trade, the conspirators did nothing fancy to launder the cryptocurrency used in the operation. The servers obtained in the name of Andrea Neumann were paid using three successive cryptocurrency accounts, each with different names but accessed from the same IP address. The third name was Wan Connie. An interlocked Wan Connie email account had been accessed from M-13’s IP address. So while the cryptocurrency itself couldn’t tie the conspirators to the hack, the interlocked infrastructure did.

The conspiracy

To prove the hack, prosecutors at trial showed how the FBI had used evidence from the crime scene, the “getaway” car, the money trail, and evidence obtained at the end point from iCloud accounts to tie the hack back to Ermakov personally and M-13 more generally. The biggest smoking gun came from matching the IP addresses to which Ermakov got his iTunes updates to the infrastructure used in the hack (or, in the case of the May 9, 2018 thefts, directly to someone exploiting Julie Soma’s stolen credentials.

All that was left in the Klyushin case was proving the conspiracy, showing that Klyushin and others had used this stolen information to make millions by trading in advance of earnings announcements. This would be the functional equivalent of tying the records stolen from Democrats (and some Republicans) to their release via Guccifer 2.0, dcleaks, and WikiLeaks.

All that was left in the Klyushin case was proving the conspiracy, showing that Klyushin and others had used this stolen information to make millions by trading in advance of earnings announcements. This would be the functional equivalent of tying the records stolen from Democrats (and some Republicans) to their release via Guccifer 2.0, dcleaks, and WikiLeaks.

At Klyushin’s trial, the government proved the conspiracy via two means: an SEC analyst presented a bunch of coma-inducing analysis showing how the trades attributed to online brokerage accounts that Klyushin and others had in their own names lined up with the thefts. The analyst explained that odds of seeing those trading patterns would be virtually impossible.

More spectacularly, prosecutors introduced Klyushin’s role with a bunch of pictures establishing that he was “besties” with Ermakov (and, eventually, that there were unencrypted and encrypted communications, along with a picture of Klyushin’s yacht, sent via Ermkaov to two guys in St. Petersburg who didn’t work for M-13 but who were making the same pattern of trades); I looked at some of that evidence here. One picture found in Klyushin’s account showed Ermakov, crashed on a chair, wearing an M-13 sticker, taken in the same period as some of the logs provided by Kroll showed hacking activity. About the only thing the FBI found in Ermakov’s iCloud account was the online brokerage account used to execute the insider trading, in Klyushin’s name, but that tied him to the trading side of the conspiracy.

As their trades began to attract attention, Ermakov and another M-13 employee attempted to craft cover stories, evidence of which prosecutors found via Apple. Prosecutors even introduced Threema chats in which Ermakov told Klyushin, his boss, not to share details about their trading clients or he might end up a defendant in a trial.

He did.

And at that trial, prosecutors were able to prove a hacking conspiracy against Klyushin using evidence and victim testimony from the crime scene, but also from other data readily available with a subpoena or warrant inside the US.

Update: Tweaked language describing secure tunnels.