Between the Annual Release of FISA Statistics and the Release of the FISA 702 Opinion, FBI Rolled Up Turla

I’m curious about the timing of the release of the FISC 702 opinion, dated April 21, 2022, approving Section 702 certificates that would last until April 21, 2023. I laid out a Modest Proposal in response to that opinion here.

In the past, the government has often released the prior year’s FISC opinion around the same time as it releases all the FISA transparency reports, which it released this year on April 28, 2023. But ODNI didn’t release the opinion itself until May 19, eight days after the FBI released a FISA-related audit that covers many of the same violative queries laid out in the FISC opinion and three weeks after the other transparency filings. The delayed release resulted in the release of significantly overlapping bad news twice, a week apart, at a time when the spooks already face an uphill climb to get 702 reauthorized before the end of the year.

One possible explanation for the delayed release is that there was a one-month delay in reapproval of new 702 certificates, meaning that ODNI held back the opinion until such time as a new opinion had replaced the old one.

But as I read, especially, a separate opinion released along with the 702 one, I couldn’t help but note that between the date when ODNI would customarily release the prior FISC authorization and the date it did, FBI rolled up the Turla malware.

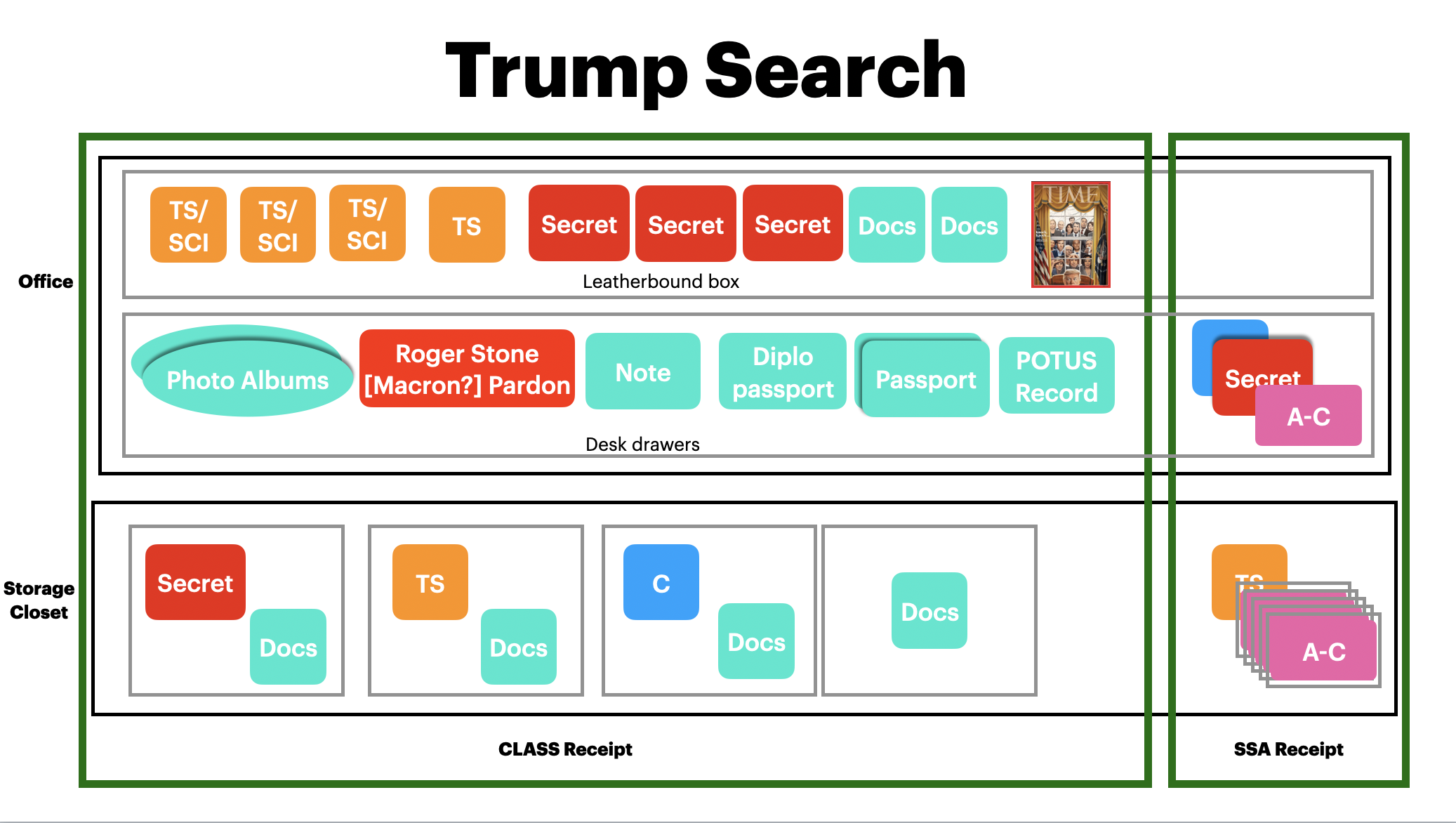

May 4, 2023: Search warrant affidavit

May 8, 2023: Planned operation

May 9, 2023: DOJ Press release; NSA press release; Joint Cybersecurity Advisory

When I wrote my post on the operation, I laid out how, starting in 2016, the FBI had learned how Turla worked via voluntary monitoring of US-based victims from whose servers the malware was launching attacks in other countries.

A key part of the affidavit’s narrative describes that monitoring process. The FBI discovered that Turla compromised computers at US Victim A in San Jose, which let the FBI monitor how the malware worked. Using US Victim A, Turla compromised US Victim B in Syracuse, which in turn let the FBI monitor what happened from there. Using both US Victims A and B, Turla compromised US Victim D in Columbia, SC, which in turn let the FBI monitor traffic. Using Victim B, Turla compromised US Victim C, in Boardman, OR, which in turn let the FBI monitor traffic.

Over seven years, then, the FBI has been monitoring communications traffic from a growing number of US victim companies that Turla used as nodes. The affidavit emphasizes that these sites were used to attack overseas targets — like the presumed German and French targets mentioned in the affidavit. Aside from the journalist working for a US outlet (who could be stationed overseas), the affidavit doesn’t mention any US collection targets. Nor does it explain whence Turla targets US collection targets.

But there were two or three companies that refused to allow the FBI to engage in consensual monitoring of their victimized servers: Victim-E, Victim-F, and Victim-G, all of which were discovered in 2021 or 2022 (Victim-F went defunct and destroyed its computers).

According to the FBI search warrant, then, it launched a global operation to roll up the Turla Snake’s many nodes around the world without the benefit of at least two US-based nodes from which it could discover other victims. That didn’t make sense to me.

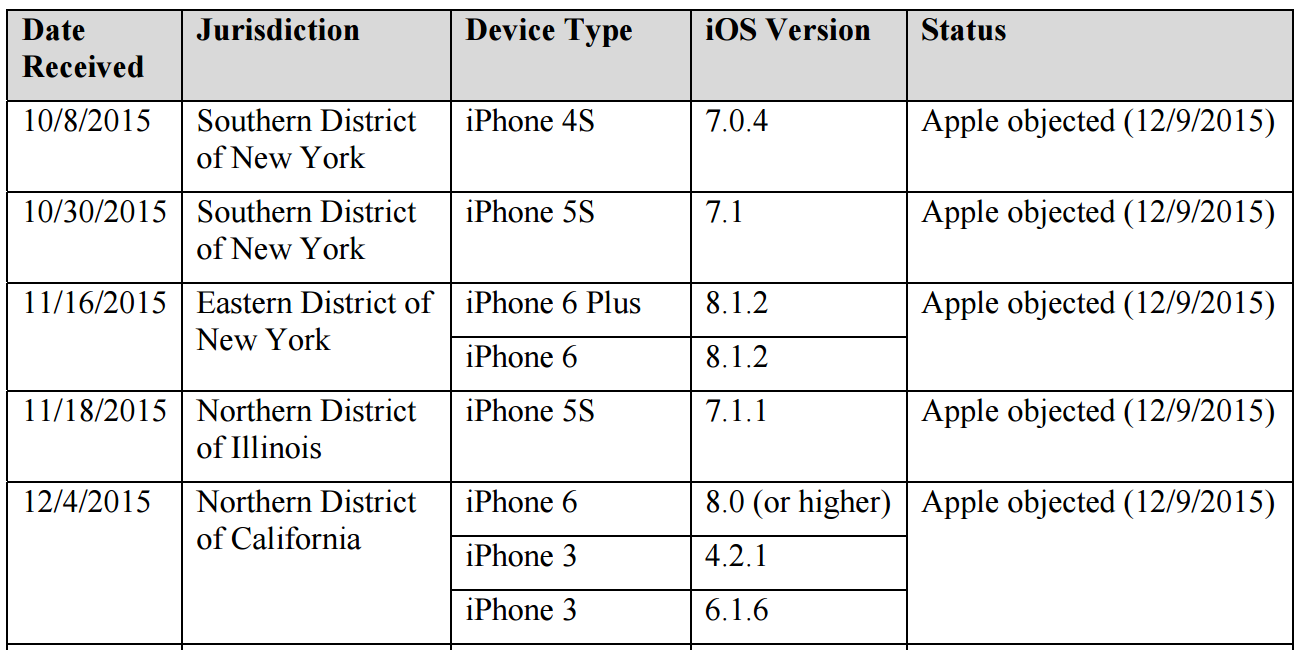

The other FISA opinion released with the 702 one sought authorization to conduct physical surveillance of two locations in the US used by an agent of a foreign power; the government uses physical surveillance to obtain data in rest on a server. DOJ first submitted the application in early 2021. FISC appointed former cybersecurity prosecutor and current tech attorney Marc Zwillinger and retired EDNY Magistrate James Orenstein as amici and conducted several rounds of briefing and a hearing. Orenstein would have still been a Magistrate in EDNY when the grand jury behind this operation was seated there in 2018; he retired in 2020.

The heavily redacted opinion itself is pretty short — just 6 pages. It explains that “the Court has little difficulty finding probable cause to believe that the intended targets … are agents of a foreign power.” It had a harder time with two other issues, though: proving that the premises to be searched “is or is about to be owned, used, possessed by … that foreign power.” Suggestions from Zwillinger and Orenstein provided limits to the order such that FISC presiding Judge Rudolph Contreras could meet that standard.

The government also noted that the data in the targeted location “might not be owned or used by” the agents of the foreign power in question. Contreras imposed a 60-day deadline for the government to destroy everything that was not.

With those limitations, Contreras approved the FISC order on September 27, 2021.

Both of these issues are common ones in cybersecurity surveillance. Hackers hijack others’ servers, and from that sanctuary, victimize others. And then hackers transport data that are the fruits of theft, not communications about such a crime, via these nodes. So one way or another, the opinion sounds like it could pertain to cybersecurity surveillance. The timing is what makes me wonder whether the order was withheld until the end of the Turla operation.

Zwillinger and Orenstein were appointed as amici in 2022 as well.

Note, there’s a technique that got authorized in the 702 opinion, first proposed in March 2021, which involved two different amici, Georgetown Professor Laura Donohue, who asked for the assistance of Dr. Wayne Chung, the Chief Technology Officer of BlueVoyant, a cybersecurity company. That discussion is even more heavily redacted. But the issues debated appear to include:

- Whether the thing obtained using 702 was included in the definition of intelligence permitted for collection

- Whether the assistance required in the US came from an Electronic Communications Service Provider (Victim A from the Turla operation was located in San Jose, and the Victim G that refused to cooperate was described as a cloud service provider located in Gaithersberg)

- Whether the assistance from the ECSP is covered by 702

- Whether the intended use of the information fit the definition of querying

- Whether NSA should have used another provision of FISA

- Whether all the targets were overseas

- What kind of minimization procedures the kind of information that would be obtained required

The 702 application is even more obscure than the physical search one. But if the latter pertains to Turla, it’s not inconceivable that the former does too.