The Government Admits 9 Defendants Spied On Under Section 702 Have Not Gotten FISA Notice

As I noted, in his opinion approving the Section 702 certifications from last year, Judge Thomas Hogan had a long section describing the 4 different kinds of violations the spooks had committed in the prior year.

One of those pertained to FBI agents not establishing an attorney-client review team for people who had been indicted, as mandated by the FBI’s minimization procedures.

In his section on attorney-client review team violations, Hogan describes violations in all four of the Quarterly Reports submitted since the previous 702 certification process: December 19, 2014, March 20, 2015, June 19, 2015, and September 18, 2015. He also cites three more Preliminary Compliance Reports that appear not to be covered in that September 18, 2015 report: one on September 9, 2015, one on October 5, 2015, and one on October 8, 2015. His further discussion describes the government claiming at a hearing on October 8 to discuss the issue that, thanks to a new system FBI had deployed to address the problem, “additional instances of non-compliance with the review team requirement were discovered by the time of the October 8 Hearing.”

But as Hogan notes in his November 2015 opinion, FBI discovered a lot of these issues because FBI had had a similar problem the previous year and he required them to review for it closely in his 2014 order. A July 30, 2014 letter submitted as part of the recertification process describes two instances in depth: one noticed in February 2014 and reported in the March Quarterly report, and one noticed in April and reported in the June 2014, each involving multiple accounts. A footnote to that discussion admits “there have been additional, subsequent instances of this type of compliance incident.”

Set aside, for the moment, the persistence with which FBI failed to set up review teams to make sure prosecutorial teams were not reading the attorney-client conversations of indicted defendants (who are the only ones who get such protection!!!). Set aside the excuses they gave, such as that they thought this requirement — part of the legally mandatory minimization procedures — didn’t apply for sealed indictments or with targets located outside the United States.

Conservatively, this significantly redacted discussion identifies 9 examples (2 reported in Compliance Reports in 2014, at least 1 reported each in each of four quarterly Compliance report between applications, plus 3 individual compliance reports submitted after the September Compliance report) when people who have been indicted had their communications collected under Section 702, whether they were the target of the 702 directives or not.

And yet, as Patrick Toomey wrote in December, not a single defendant has gotten a Section 702 notice during the period in question.

Up until 2013, no criminal defendant received notice of Section 702 surveillance, even though notice is required by statute. Then, after reports surfaced in the New York Times that the Justice Department had misled the Supreme Court and was evading its notice obligations, the government issued five such notices in criminal cases between October 2013 and April 2014. After that, the notices stopped — and for the last 20 months, crickets.

We know both Mohamed Osman Mohamud — who received a 702 notice personally — and Bakhtiyor Jumaev — who would have secondary 702 standing via Jamshid Muhtorov, with whom he got busted — had their attorney-client communications spied on. But that wasn’t (damn well better not have been!!) 702 spying, because both parties to all those conversations were in the US.

These are 9 different defendants who’ve not yet been told they were being spied on under 702.

Why not?

The answer is probably the one Toomey laid out: that even though members of a prosecutorial team were listening in on attorney-client conversations collected under 702, DOJ made sure nothing from those conversations (or anything else collected via 702) got used in another court filing, and thereby avoided the notice requirement.

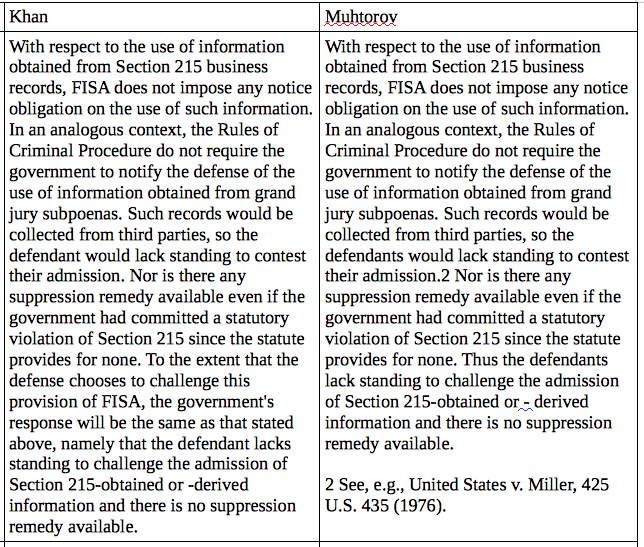

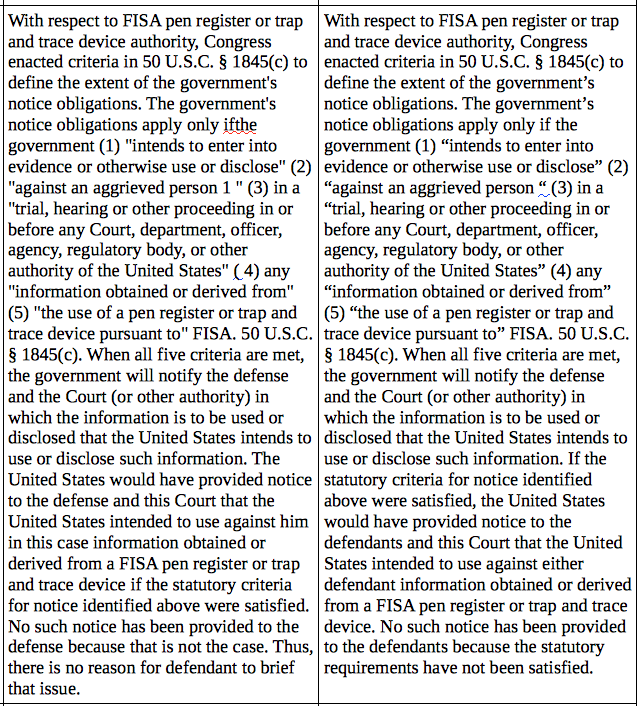

Based on what can be gleaned from the public record, it seems likely that defendants are not getting notice because DOJ is interpreting a key term of art in Fourth Amendment law too narrowly — the phrase “derived from.” Under FISA itself, the government is obliged to give notice to a defendant when its evidence is “derived from” Section 702 surveillance of the defendant’s communications. There is good reason to think that DOJ has interpreted this phrase so narrowly that it can almost always get around its own rule, at least in new cases.

It is clear from public reporting and DOJ’s filings in the ACLU’s lawsuit that it has spent years developing a secret body of law interpreting the phrase “derived from.” Indeed, from 2008 to 2013, National Security Division lawyers apparently adopted a definition of “derived” that eliminated notice of Section 702 surveillance altogether. Then, after this policy became public, DOJ came up with something else, which produced a handful of notices in existing cases.

Savage reports in Power Wars that then-Deputy Attorney General James Cole decided that Section 702 information had to have been “material” or “critical” to trigger notice to a defendant. But the book doesn’t provide any details about the legal underpinnings for this rule or, crucially, how Cole’s directive was actually implemented within DOJ. The complete absence of Section 702 notices since April 2014 suggests DOJ may well have found new ways of short-circuiting the notice requirement.

One obvious way DOJ might have done so is by deeming evidence to be “derived from” Section 702 surveillance only when it has expressly relied on Section 702 information in a later court filing — for instance, in a subsequent FISA application or search warrant application. (Perhaps DOJ’s interpretation is slightly more generous than this, but probably not by much.) DOJ could then avoid giving notice to defendants simply by avoiding all references to Section 702 information in those court filings, citing information gleaned from other investigative sources instead — even if the information from those alternative sources would never have been obtained without Section 702.

So these 9 mystery defendants don’t tell us anything new. They just give us a number — 9 — of defendants the government now has officially admitted have been spied on under 702 who have not been told that.

As I noted, Judge Hogan did not include this persistent attorney-client problem among the things he invited Amy Jeffress to review as amicus. Whether or not she would have objected to the persistent violation of FBI’s minimization procedures, a review of them would also have given her evidence from which she might have questioned FBI’s compliance with another part of 702, that defendants get notice.

But DOJ seems pretty determined to flout that requirement going forward.