From emptywheel: Thanks to the generosity of emptywheel readers we have funded Brandi’s coverage for the rest of the trial. If you’d like to show your further appreciation for Brandi’s great work, here’s her PayPal tip jar.

It was a risky move by Proud Boy defendants Zachary Rehl and Dominic Pezzola to take the witness stand. So it is for any criminal defendant. A skilled prosecutor can unwind even the most robust witness without alerting their subject to it until it is too late.

It took four months of hearing evidence in the Proud Boys seditious conspiracy trial—which enters closing arguments on Monday—but this past week, jurors got it straight from the source when two of five Proud Boys on trial testified for once and all: Zachary Rehl and Dominic Pezzola.

Their respective testimonies were often combative, the tension frequently high. Each man started out confident and cocksure, but the more Justice Department prosecutors pushed Rehl and Pezzola around the edges of their testimony, the more the men relinquished whatever tight grip they had over themselves when testifying under the far more amenable gaze of their own attorneys.

Both sides have now rested and on Friday, jury instructions were issued. All that is left are closing arguments. It will be those final words that the jurors will have ringing in their ears when the book finally closes on this trial. But no matter how sweeping or evocative those final arguments may be, some of the trial’s most potent moments, for better or worse, will belong to the testimony of two Proud Boys who favored speaking instead of silence.

ZACHARY REHL: “Not that I recall.”

Zachary Rehl was one of two Proud Boy defendants to take the witness stand, and when under cross-examination by Assistant U.S. Attorney Erik Kenerson, his tone was often sharp, his face taut and eyes hard as he grew impatient with a barrage of questions from the federal prosecutor.

The 37-year-old man’s face, which looks much younger than his years, was more softly animated when he spoke to his own attorney Carmen Hernandez. With her, his testimony would spill out rapidly as he told a jury that has now heard evidence for four months: there was no conspiracy to storm the Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021. There was no plan to stop proceedings nor impede law enforcement from doing their duty, he said again and again under oath.

Police, he claimed, let protesters pass through barriers. He said he never saw any significant violence directed at law enforcement and didn’t realize there had been such conduct until later, though on the stand he conceded to witnessing “scuffles” between rioters and police. (He would distinguish “rioters” from “protesters” often.) But, again, he offered, there was no attempt by him to assault any officers while he was on Capitol grounds.

On this point, the son and grandson of a Philadelphia police officer was adamant and he would turn to face the jury as he said this, his eyes searching theirs to validate him.

But he didn’t turn to face the jury when Kenerson started walking Rehl through a sequence of video clips from the 6th, including those that his attorney tried and failed to keep out of evidence after they emerged following a weekend break in proceedings.

The prosecutor had Rehl identify himself in footage shot close-up and Rehl positively identified himself as wearing a black jacket, black goggles, a camouflage hat with orange writing, and a gaiter that appeared to have a chevron or some sort of triangular pattern on it.

When Kenerson asked Rehl if he recalled being by the giant media tower erected outside of the Capitol on Jan. 6 before entering the building, Rehl readily offered, he was “around there.”

But when asked if he could recognize a man in attire appearing identical to his at a slightly greater distance near this location, Rehl started to lock up. The man appeared to be wearing the same clothes Rehl had just identified as his own at closer range. And at this angle, appearing at a distance, the man appeared to be holding something dark in his hand. Rehl, with his brow furrowed, leaned into the monitor at the witness box and told the jury he couldn’t say what it was that the man was holding.

Zooming in and out, the footage rolling back and forth, Kenerson pressed: Was this, in fact, his attire? Was this man Rehl? Was this his arm extended toward officers as he held something in his hand?

“A lot of people wore the same clothes that day”, Rehl said. “I can’t confirm or deny that’s me.”

For several tense minutes, Rehl could not or would not confirm hardly anything presented to him including whether the color of clearly black sunglasses or goggles covering the man in question’s face in the sequence were in fact black.

“Are they pink?” Kenerson asked incredulously, triggering a storm of objections from defense counsel.

Rehl’s demeanor became more irritated from that point forward and the gloves came off. He insisted the footage was “very blurry,” although he would eventually concede as cross continued that the gaiter in question was “close” to the pattern of his own. The coat was similar too, but he wouldn’t say whether the more distinctive camouflage hat was his. Going around and around like this with Rehl, Kenerson eventually asked the Proud Boy outright if he assaulted any police before entering the Capitol with pepper spray.

“No,” Rehl said.

Playing footage frame by frame that prosecutors said came from a bodyworn police camera, a man who prosecutors suggest is Rehl has a device in his hand.

“I can’t tell but I would imagine it’s an OSMO,” Rehl said, referencing a small camera or recording device.

“Does a small recording device usually have streams coming out of them?” Kenerson asked.

Rehl said he couldn’t see a canister and could only see a hand. He conceded he could see “streaks” in the footage but not “spray” in the direction of police. He questioned the integrity of the evidence. The hand was holding something, he admitted, but if it was his hand, he said, it would be a camera.

“Mr. Rehl, you’ve had overnight to think about it. You were spraying in the direction of police officers near the media tower on Jan. 6, 2021?” Kenerson asked.

Rehl, who had been so emphatic of so much else in his testimony about Jan. 6, or about himself, or the Proud Boys as a whole, replied coolly: “Not that I recall.”

The prosecutor elicited from Rehl that after he left the area near the media tower, he was ultimately able to advance further onto the upper west plaza of the Capitol before going inside. Positioned high above, and as police were being overrun on both the west and east sides of the complex, he snapped a photo and narrated to Proud Boys in a text sent at 2:29 p.m: “civil war started.”

On redirect, he didn’t deny sending the message and instead claimed he was “basically mocking all the news we were hearing prior to the event,” he said.

He added that he was being “ironic.”

“It’s all just a very peaceful scene, we were just standing around,” Rehl told his attorney.

Hernandez tried to steady the ship: “Is that your opinion today that everything that happened that day was irony?”

“Oh no no no,” Rehl said.

When he went through his phone, after the fact, he said he realized what had happened.

“It was a terrible day, a lot of bad stuff happened,” he said.

Nonetheless, he told the jury he was “proud of the turnout.” But on Jan. 7, as he started to “go through things and see what happened that day” he didn’t want to “associate” with it.

And then with a remark that could cut both ways for a jury who had only just watched Rehl’s temper rise and flare, Rehl said: “Previously, I tried to have a good persona and that’s what I try to portray.”

The scenes that unfolded around him as he got past police and pushed inside the complex didn’t strike him as unusual.

“Nothing out of the ordinary for a protest?” Kenerson would ask him before ending Rehl’s cross-examination.

The prosecutor’s question was a direct quote from Rehl’s time on direct when described what he witnessed in Washington some 800 days ago now.

“Nothing out of the ordinary for a protest,” Rehl repeated.

“No further questions,” Kenerson said.

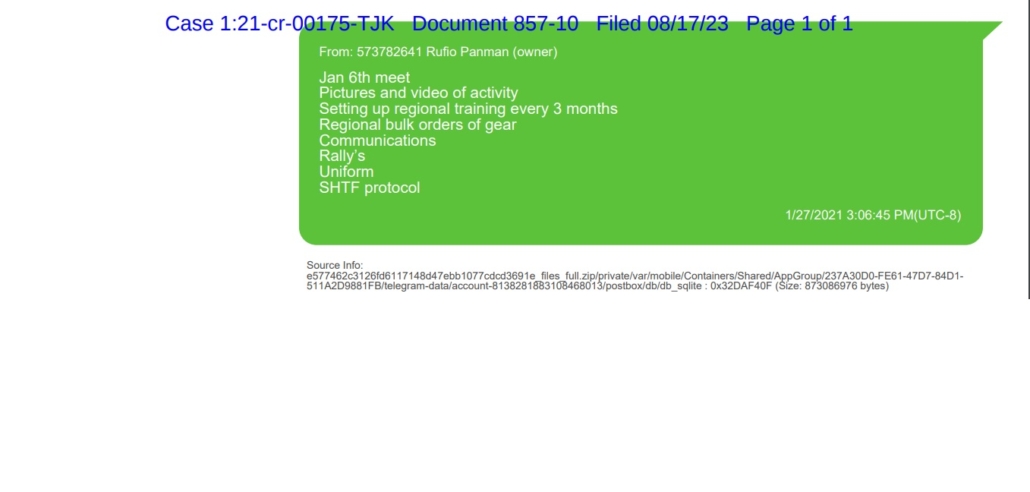

Isaiah Giddings, (who Rehl testified came to D.C. with him and at least two other individuals, Brian Healion and Freedom Vy) said in his statement of offense to law enforcement that Rehl had asked other rioters on the 6th whether they had any “bear spray.” According to Giddings’s statement, Rehl never got it.

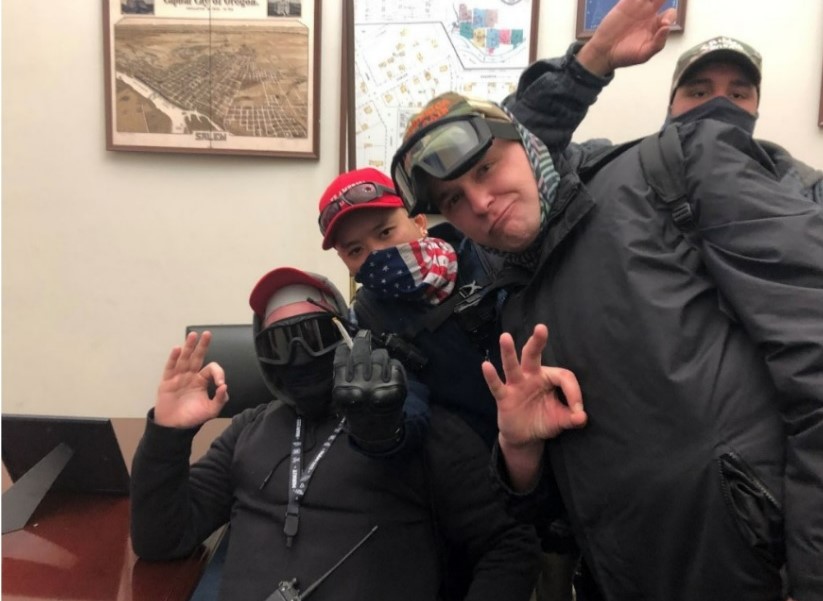

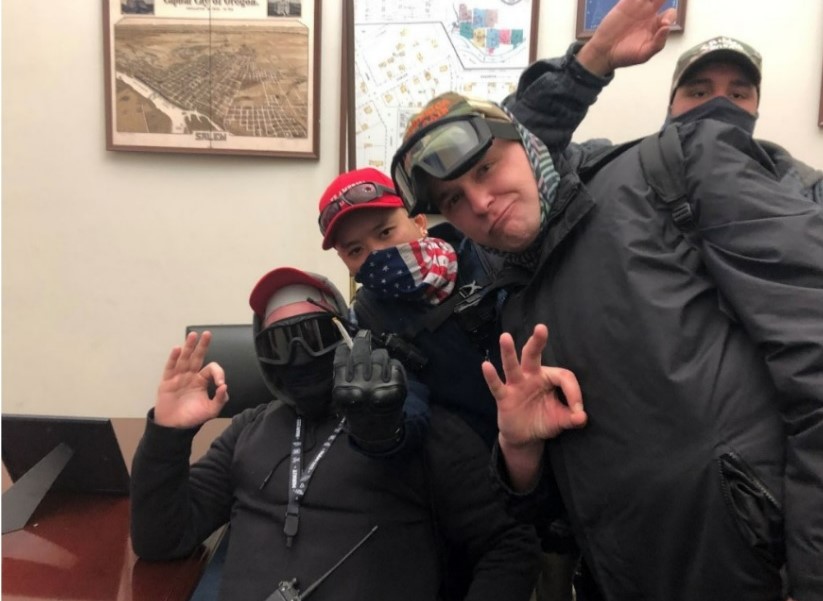

In court, Rehl denied realizing he was in Senator Jeff Merkley’s office when he stopped in to have a smoke. But he admitted to lighting up and told the jury he regretted it. So many others were milling around smoking inside, he explained, he figured he would do the same.

When asked on his last day on the stand, Rehl was able to identify his fellow Philly Proud Boy Giddings as one of the individuals in the lawmaker’s office with him. When Kenerson had asked him if he could remember what Giddings wore on the 6th, he couldn’t recall. When Hernandez played a video from inside Merkley’s office for the jury, he said he “thought Freedom and Brian might be there but I don’t see them.”

“The door was already open when I got there,” he said.

Rehl, perhaps still smarting from Kenerson’s cross, quipped that he didn’t think he “would be charged nine felonies” for smoking in the Capitol.

When former West Virginia Proud Boy leader Jeff Finley testified, Assistant U.S. Attorney Nadia Moore asked Finley if it was Rehl’s idea to go inside the Capitol on Jan. 6.

“We discussed it. I was part of that discussion,” Finley testified in March.

“My question is: did he ask you, ‘you wanna go in?’” Moore said.

Finley shrugged his shoulders as he sat in the witness box, his face mostly emotionless, and said: “I guess.”

He said he understood at the time they entered the Capitol, police did not want them there. Rehl would deny having a clear understanding of this when he would finally testify weeks later.

Finley also admitted that he stopped by Merkley’s office and took a selfie. He said he took it in the doorway of the lawmaker’s office. After the 6th, Finley began deleting photos and advised other Proud Boys to do the same. He told the jury it was because he feared doxxing by the left if their devices were captured. Like Rehl, Finley was often curt with prosecutors but unlike Rehl, far more forthcoming. And unlike Rehl, Finley had already pleaded guilty, copping to a misdemeanor charge for entering restricted grounds. He’s serving a 75-day prison sentence.

Jurors saw text messages too that Rehl, a former U.S. Marine, sent to his mother on the night of Jan. 6 when he told her how “fucking proud” he was of the “raid” on the U.S. Capitol.

It had “set off a chain reaction of events throughout the country” he gushed.

He sent his mother a message in December 2020 as well after things had turned bloody in D.C. following a pro-Trump “Stop the Steal” rally.

Four Proud Boys had been stabbed and a woman, who Rehl told the jury he suspected was “antifa,” had been brandishing a knife on the street that night.

Footage that circulated among the far right network on their private channels as well as on public ones on Parler and Telegram showed the woman being cracked over the head with a helmet before crumpling to the ground. Impressed and celebratory “oohs” and “ahs” emanated from Proud Boys surrounding the grim scene.

Prosecutors argue this graphic footage was something that Rehl and Proud Boys used as a recruitment tool ahead of the 6th and that it was a point of pride for them to display their violent tendencies.

Records extracted from Rehl’s device after his arrest show he sent the video to his mother.

He blanched at the suggestion from prosecutors that he shared the clip with his mother because he was proud of the violence and any Proud Boys’ handiwork in it.

To the contrary, he testified, he didn’t want his mother to think Proud Boys were the aggressors.

“I didn’t want my mom of all people thinking we’re just going around being freaking bullies to people in the street,” Rehl said in court last week.

When squaring off with the Justice Department, however, Kenerson brought out a series of text messages from 2020 that he argued showed Rehl had long wanted to “fast track” members into the Proud Boys who were the bullying type. He wanted members who were “ready to crack skulls” and wanted recruits “physically ready” for rallies.

Rehl disagreed with the interpretation. He was joking, he said, when he told a fellow Proud Boy in one message he wanted all of their guys “to be jacked. LOL”

“I was looking for guys who could hold their own. Doesn’t mean looking for violence,” he told Kenerson sharply.

Rehl called much of this talk “street language.”

There was always some such euphemism Rehl had on hand to describe his communications. He defended the Proud Boys as no more than a fraternity that liked to drink hard, “talk shit” or “bluster” and dabble in political activism to have their “voices heard” when they felt the need or weren’t partying.

That dabbling, he admitted, included trips where he and his chapter members traveled from their Pennsylvania homes to attend events where they wanted to make a presence, like in Kalamazoo, Michigan, or St. Louis, Missouri, or Fayetteville, North Carolina. Or Washington, D.C.

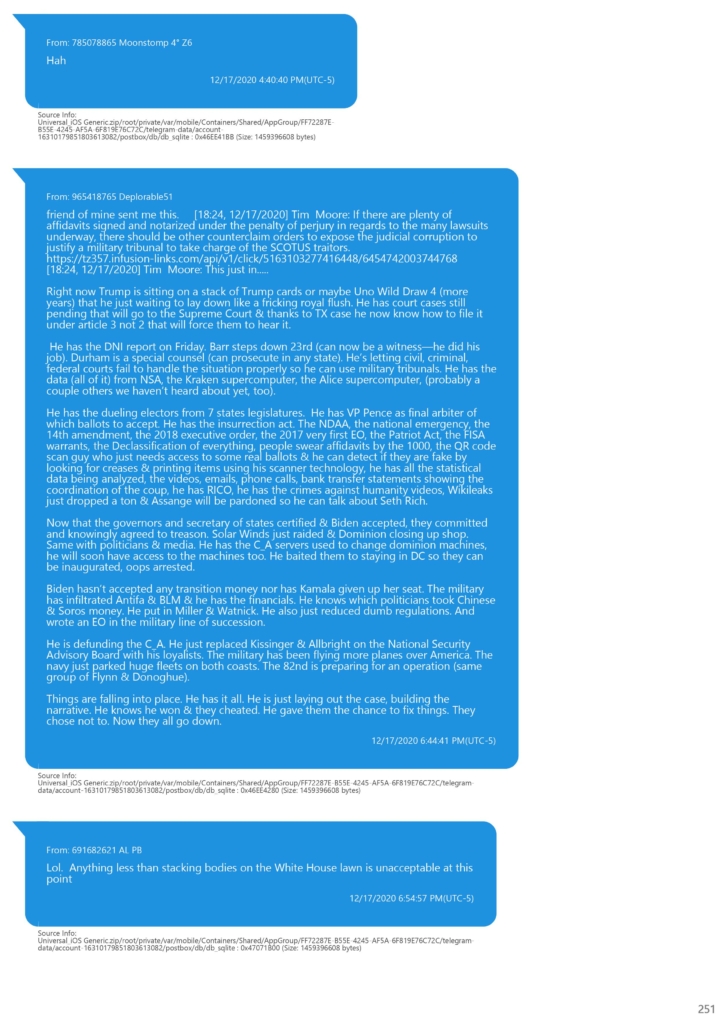

Texts in evidence between Rehl’s co-defendant Joe Biggs and Henry Tarrio dated Dec.19 offered jurors a look into where the Proud Boys seemed to stand at that time. It was Biggs who wrote that when it came to recruitment efforts, they needed to forgo finding “losers who wanna drink.”

“Let’s get radical and get real men,” Biggs told Tarrio on Dec. 19.

In this same exchange, Tarrio replied: “The drinking stuff helps mask and recruit. Although some chapters don’t leave their bars and homes.”

“No one looks at us from our side and sees a drinking club,” Biggs responded later in the chain to Tarrio. “They see men who stand up and fight. We need to portray a more masculine vibe.”

Biggs would buy his airline tickets to D.C. the next day, telling Tarrio he was booked from Jan. 5 to Jan. 7.

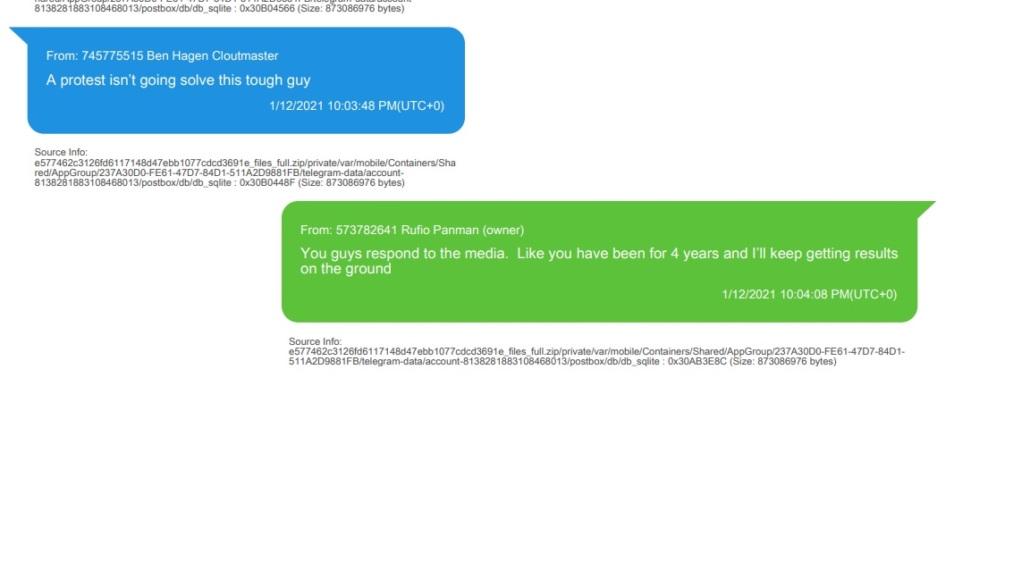

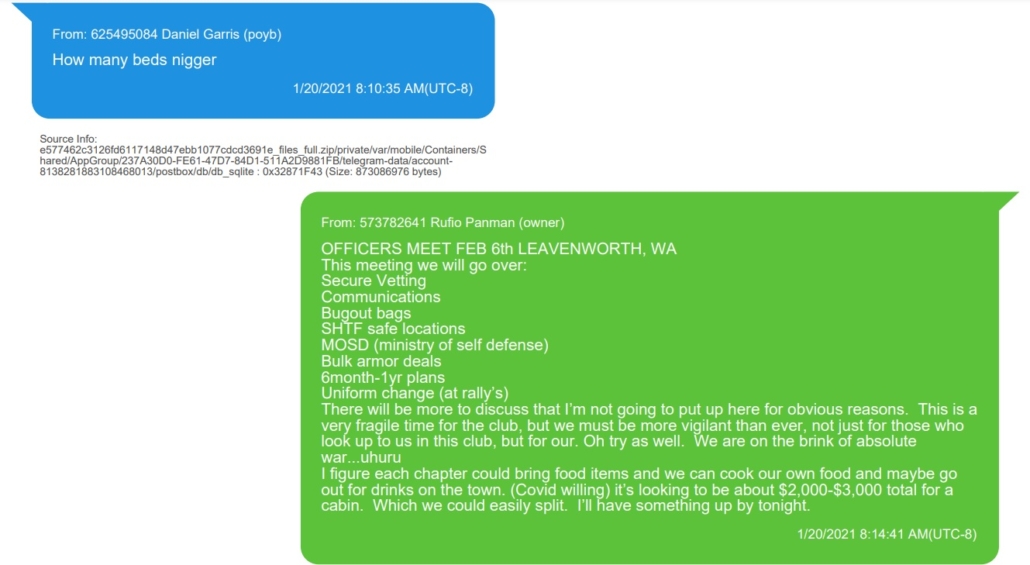

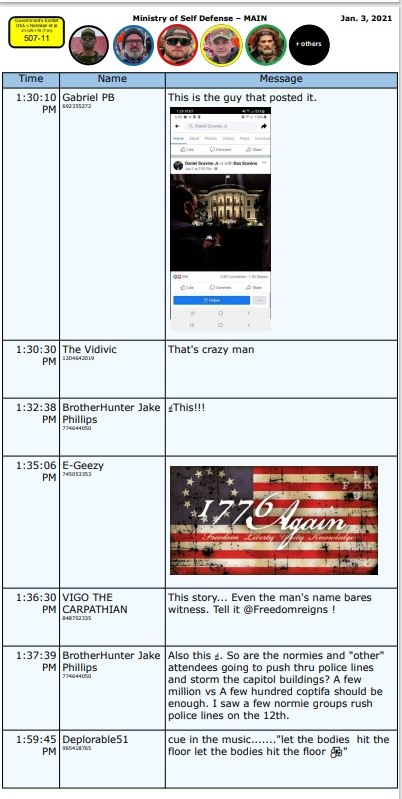

Within 24 hours of that conversation between Biggs and Tarrio, the Ministry of Self-Defense was stood up.

According to prosecutors, it was then that Zachary Rehl, Ethan Nordean, Charles Donohoe, and a slew of other Proud Boys like Aaron Wolkind and John Stewart—alleged “tools” of the conspiracy—were added to MOSD. Donohoe has pleaded guilty to conspiracy to obstruct an official proceeding and assaulting an officer.

Jeremy Bertino, who has already pleaded guilty to seditious conspiracy and testified against the defendants at trial, would come aboard a few days later on Dec. 23. As for Dominic Pezzola, prosecutors say the Rochester, New York Proud Boy, and former U.S. Marine wouldn’t join the conspiracy until Jan. 2, 2021, when he was officially added into the MOSD chat group.

Sitting inside the E. Barrett Prettyman courthouse just a few blocks from where he once stood shoulder to shoulder with rioters wildly overwhelming police, Rehl resisted the Justice Department’s allegations about MOSD’s real purpose and he tried to slap away suggestions that Proud Boys relied on violence as a key mechanism bonding their “western chauvinist” group.

When prosecutors showed the jury evidence tied to an August 2020 rally organized against human sex trafficking and sexual assault in Fayetteville, North Carolina, Rehl grew particularly pointed. The rally was uneventful despite concerns that it would turn ugly when busloads of “antifa” would show up. (A rumor that circulated widely and never came to pass). Kenerson then showed texts suggesting Rehl’s history of being primed to take matters into his own hands when he saw fit.

Pulling up messages extracted from Rehl’s devices, Kenerson asked him if he said he wanted to “fuck up antifa” at the North Carolina rally if they showed. Without missing a beat, Rehl said in court: “Actually, you know what, yes I did.”

And, he added, he would have used “any can of mace I had” to stop anyone who would have stood in opposition to the people attending that rally that day.

“You said you were going to beat them with a 12-inch dildo you picked up?” Kenerson asked.

“Yes. Again, preparing for the worst,” Rehl said.

Rehl said Proud Boys only ever “prepared for the worst.”

Rehl said he wanted “the legal process to play out” on Jan.6 and his intentions were well-meaning.

“I didn’t go in until I thought there wasn’t anyone in there,” he has said. “The Capitol was a public building. I thought it was fair game to go in.”

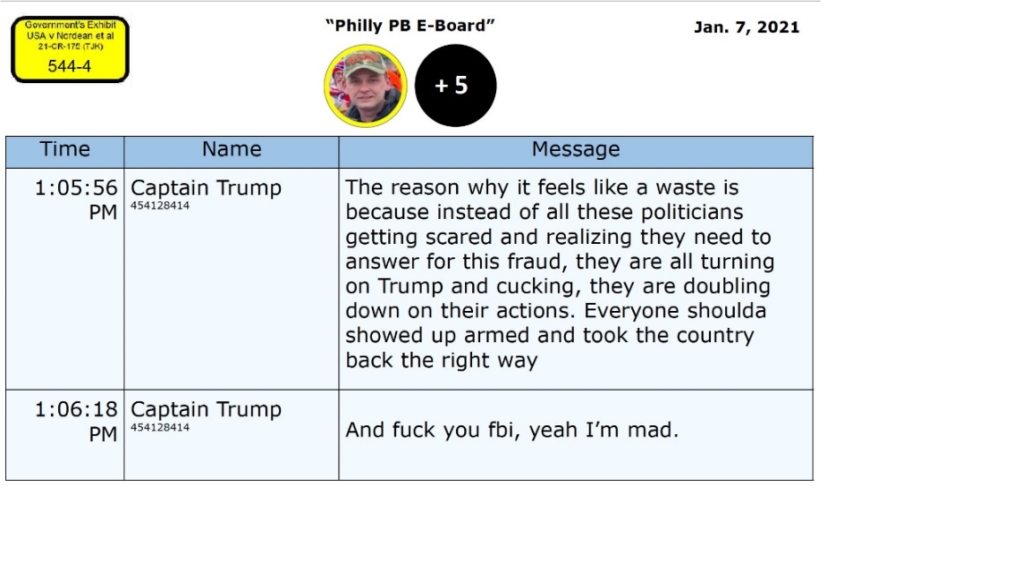

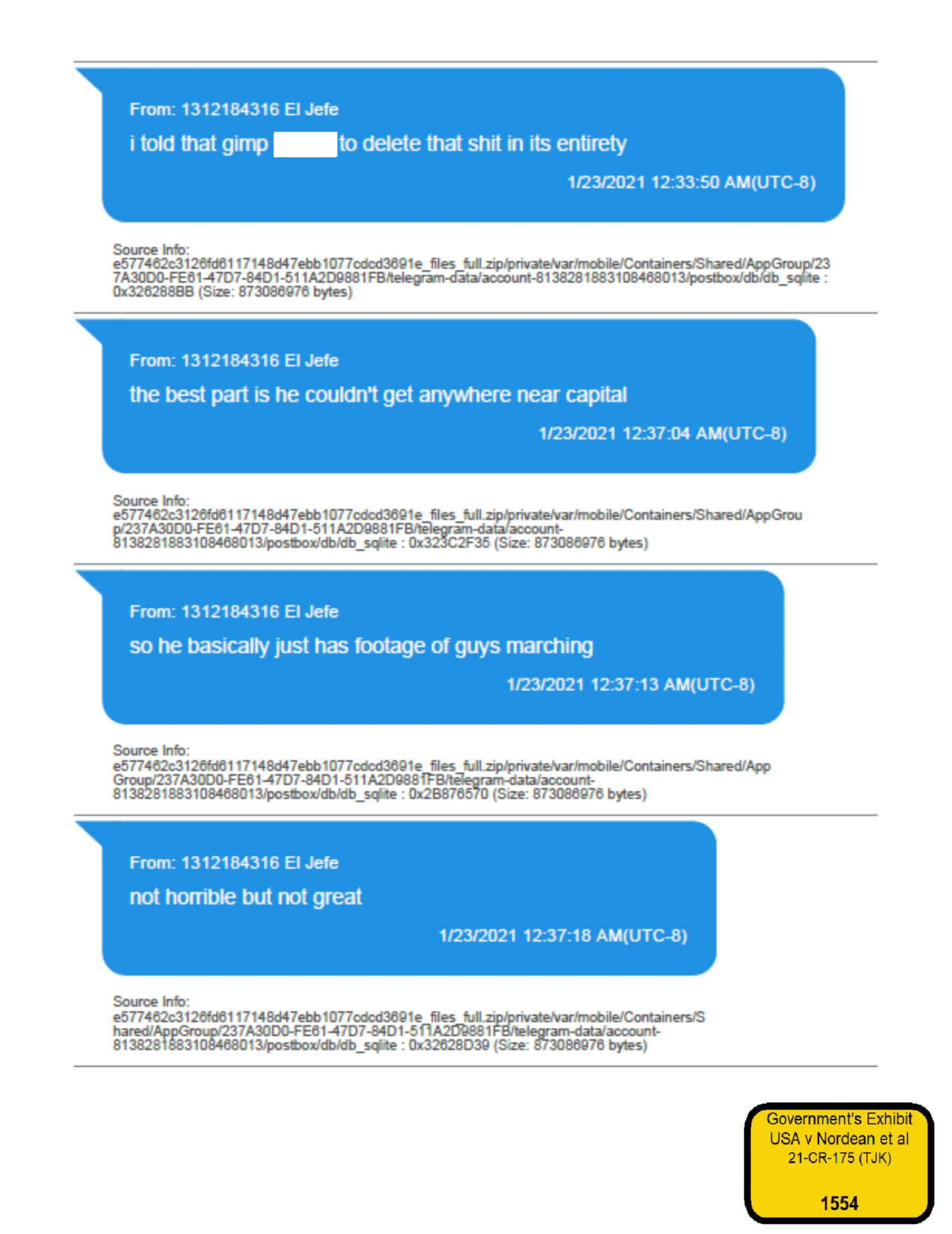

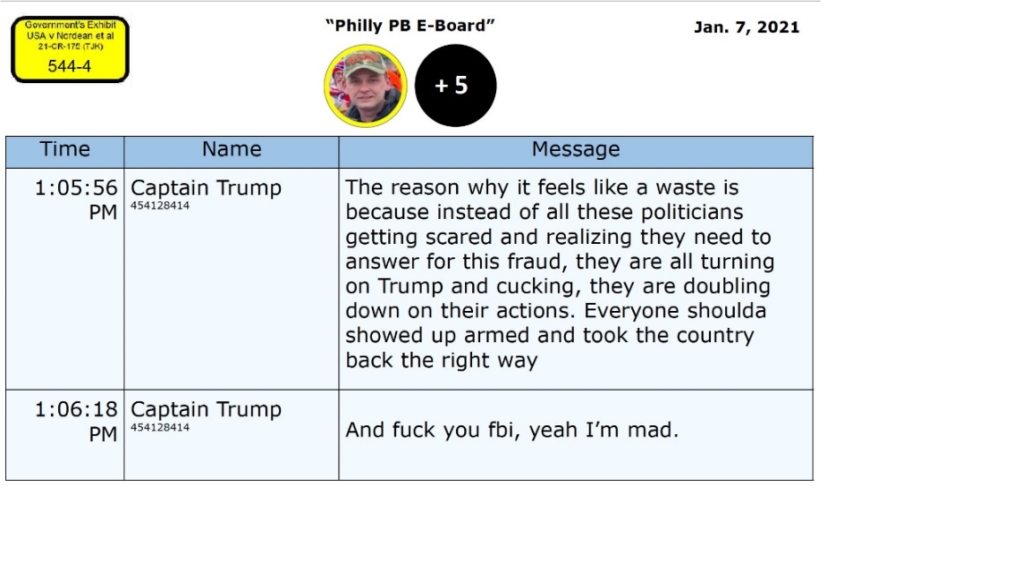

On Jan. 7 in a Proud Boy chat entered into evidence dubbed “Philly PB E-Board,” Rehl lamented in the cold morning light: “Looking back, it sucked. We shoulda held the capital. After Trump conceding today, it all seemed like a waste.”

Another Proud Boy, using the handle “Rod (Venezuela)” offered, “they should have let them finish the counting and when they didn’t accepted [sic] the challenges, rush in and set fire to that shit.”

“Yup,” Rehl replied 24 minutes later.

Rehl told Kenerson, “I see what you’re trying to do here,” and said his reply was to something else in the chat thread.

In another message from Jan. 7, Rehl wrote on the “E-Board”: “The reason it feels like a waste is because all of these politicians getting scared and realizing they need to answer for this fraud, their [sic] all turning their back on Trump and cucking, they are doubling down on their actions. Everyone shoulda showed up armed and took the country back right away. And fuck you FBI yeah I’m mad.”

Rehl testified on direct that he believed Trump’s “last stand” to change the election results had been in December. He said people had held out hope that Trump could “pull a rabbit out of his hat” on the 6th but he also testified that he knew better.

Personally, he said, he didn’t think Trump could pull a rabbit from his hat. He vowed over and over in court that he wanted a legal, constitutional process to unfold. There was never a conspiracy among him or any other Proud Boy to stop those processes or obstruct Congress from taking the necessary steps in the nation’s transfer of presidential powers.

“I said some fucked up shit the day afterward,” Rehl told Kenerson on April 17.

“But you just testified, you were only [concerned] about voting and yet you concluded, ‘everyone shoulda showed up armed?’” Kenerson asked.

“Shoulda, woulda coulda. As opposed to the legal way,” Rehl said. “We didn’t do it that way.”

DOMINIC PEZZOLA: “Corrupt trial… fake charges”

Things had started out strong for Dominic Pezzola when he first took the witness stand this past week. He didn’t look anything like the man in the video footage jurors had seen of him for several weeks, particularly as the trial first began and prosecutors shared evidence of things like Pezzola’s victory smoke inside of the U.S. Capitol after he bashed open a window and hoisted himself and other rioters inside.

The former Marine—a battalion known for its “first in, last out” mentality—was one of the first rioters to get inside the Capitol.

He faces a slew of charges alongside his co-defendants though he is unique in that he faces a robbery charge for his alleged taking of a police riot shield from U.S. Capitol Police officer Mark Ode. Ode testified at trial in February that his experience on Jan. 6 was “terrifying” as he scrambled to replenish officers who were being overwhelmed by rioters invading the building and grounds.

Rioters were using “some type of chemical spray;” he testified and at one point “it looked like a [person was holding a] small fire extinguisher walking around spraying officers.” It took Ode more than 10 minutes to recover his vision after he was doused.

Under questions from prosecutor Nadia Moore on Feb. 7, Ode said when he was knocked to the ground it was because he was being pulled down as he clung to his shield with one hand before it was wrestled away from him.

On the witness stand, in a suit and tie, and sometimes with dark-rimmed glasses framing his face, salt and pepper hair, and beard neatly cut, Pezzola started his testimony by communicating what sounded a lot like genuine remorse about what had happened.

“I’m ready to do this,” Pezzola told attorney Steven Metcalf on first day before the jury. “I’m taking the stand today to take responsibility for my actions on Jan. 6 and I’m also taking the stand to explain how these men that I’m indicted with should not be roped into my actions.”

Willing to cast himself apart from his co-defendants, Pezzola first couched his testimony with a folksy, warm delivery.

“There was no conspiracy, it never existed,” Pezzola said.

It was “the craziest damn thing,” he testified.

“So, I got caught up in the craziness. I trespassed at the first breach, second, I think there may have been a third, I basically trespassed all the breaches and during the scuffle and whole shield incident, I did grab onto the shield and pulled onto it for fear of my own life because deadly force was being used on us by police,” he said.

Pezzola would tell the jury that he acted out a flash of adrenaline that coursed through his body and made him feel as if he were on “autopilot.”

When he grabbed the shield it happened in a “split second,” he said. Someone else had grabbed it from police, he claimed, and then he grabbed it. And then, he turned to the jury while he confidently declared: “And we’ll have the proof to show this.”

The Rochester, New York Proud Boy said he was upset as he “watched mothers grabbing their children to get them out of the way to avoid flashbangs.” (The next day on the witness stand he would clarify, “children” meant teenagers.) Elderly protesters, he said, had their “eyes split open” and people had “faces full of pepper spray.”

“I was upset,” Pezzola said.

What fueled his outrage to the point that he began screaming at police, he testified, was an injury sustained by another man, rioter Joshua Matthew Black. Black, who is not a Proud Boy, was found guilty this January for entering and remaining on restricted grounds with a deadly weapon. Black was carrying a knife and made it all the way to the Senate floor despite taking a munition to the face shot at him by police who were repelling him, Pezzola, and thousands of others in the crowd.

Notably, Black posted social media videos after the 6th saying that he joined the mob and crossed barriers to get inside the Capitol because he wanted to “plead the blood of Jesus over it.”

Black also claimed that he was shot in the face while he was attempting to help a police officer who “was on the ground with boots coming down on him.”

Pezzola said after Black was shot, he got in closer for a “bird’s eye view of the damage it had done to him.”

“I knew if it had been a few inches higher that shot would have been fatal,” he said.

On direct, Pezzola spent considerable time telling jurors he was in “disbelief” of how police treated “unarmed crowds just pushing against riot shields.”

Things were “dire,” for them he testified. Things were “deadly.”

Pezzola never saw combat during his time in the military but he compared the use of less-than-lethal munitions by police on the 6th akin to being “underfire by a machine gun or something.”

The military had taught him to ignore his flight response, he said. He claimed “flash bangs” soared into the crowd at a rapid clip but he wasn’t going to turn around or walk away. He was going to “neutralize the danger,” he said.

Whether or not tales of his perceived heroics in the face of bodily harm were convincing to jurors, there was a palpable missing link in his narrative.

Pezzola expounded on direct about “rubber bullets” whizzing past his eyes, head, and face. Yet at no point over the months of evidence presented from either side, has any video or photographic evidence emerged showing Pezzola hoisting the police riot shield in a defensive posture over his head or face. On the stand he said he covered his head and remembered bullets hitting right by where his head would have been, but those flew by, he claimed, when he was on the ground in the scuffle.

When Kenerson pressed him, Pezzola couldn’t recall the moment he might have used the shield to cover his head. It was a “fog of war type thing,” he said. It was a “vague recollection.”

Footage did, however, show Pezzola carrying the shield, ascending Capitol steps with the shield, and then using the shield to smash apart a window. He also found time to take a selfie with it. In other video footage presented in court, Pezzola can be heard replying “yeah” when a man asks him if he had stolen a police shield.

Pezzola said he only said that to get the person asking questions “out of my hair.”

Once he was atop the scaffolding, video evidence shows Pezzola screaming at police: “You better be fucking scared! Yeah, you better be fucking scared! We ain’t fucking stopping. Fuck you. You better decide what side you’re on motherfuckers. You think antifa is bad, just you wait.”

In court, Metcalf asked Pezzola: “Did you use that shield to damage any property?”

“I did. When I made it up to the terrace… I did break one pane of glass. One. Someone used a two-by-four… it’s been proven over and over it was less than $1,000,” Pezzola said.

This is a point that he emphasized more than once as he testified, saying that each pane only cost $774. Further, according to Pezzola, a pane to the left of the one that he broke with the riot shield was already shattered by the two-by-four and therefore: “I struck a completely destroyed pane of glass with a shield,” Pezzola told AUSA Kenerson.

“I wouldn’t consider it a pane anymore,” he said.

When Kenerson asked him if he was saying he thought he did no damage, Pezzola smiled wryly at the attorney and told him he was just “twisting his words.”

Where he had been cool, calm, and seemingly collected on direct, Pezzola’s demeanor changed abruptly on cross. He grew more defensive and his tone more abrasive and angry. He smirked regularly or laughed under his breath at Kenerson’s questions.

“Your goal of busting the window was to have someone to listen to you?” Kenerson asked.

“Correct,” Pezzola said.

They were there to express their First Amendment rights, he said. They were “trespassing,” he admitted, but this was the way to “have their voices heard.”

“And this was the way to get the government to listen to you?” Kenerson asked again, footage of him entering the Capitol still on the screen for jurors.

“At this moment? Correct,” Pezzola said.

Besides a claim of self defense from police he deemed overzealous, the Proud Boy and his attorney also played down the alleged robbery of the shield by playing up the fact that Pezzola gave the shield back to another police officer before leaving the building. Nonetheless, on cross, the 43-year-old Proud Boy said that was a “last-minute decision.”

Pezzola met with Charles Donohoe after he got the shield and together, they and Proud Boy Matthew Greene of New York, who testified at trial and has pleaded guilty to conspiracy and obstruction already, moved toward a concrete wall. Donohoe would help him carry the shield for a time, Pezzola affirmed. Jurors also saw a text message Donohoe sent to Rehl and other Proud Boys on Telegram moments after Pezzola got the shield.

When describing his military service to the jury, Pezzola took pains to highlight his experience with antiarmor rockets and crowd control, but in fact, he was never a military police officer, and his very limited experience using flash bangs was restricted to his short stint in the Marines more than 20 years ago. When prosecutors asked him if he was aware that police used sting balls on Jan. 6, a device that delivers less damage than a flash bang, Pezzola refuted it.

Whatever was used, they were used improperly, he said.

When Kenerson asked Pezzola how he knew this to be true, he elicited that the only training the Proud Boy had received on crowd control was from a few handouts he received while serving in the military.

He had no training on “sting balls” he conceded, but that didn’t stop him from offering his non-expert testimony on their deadliness.

“You’ve never worked with police and you have never taken their protocols?” Kenerson asked.

“No,” Pezzola replied. “But I know police brutality when I see it.”

“So the standard you’re applying here is the Dominic Pezzola standard?” Kenerson said.

“You don’t need to be trained to know that an explosive can kill you,” he said.

Pezzola emphasized again how he was “afraid for his life” and then footage played in court of him hoisting the riot shield in the air—though not defensively over his head—while he chanted “USA! USA! USA!”

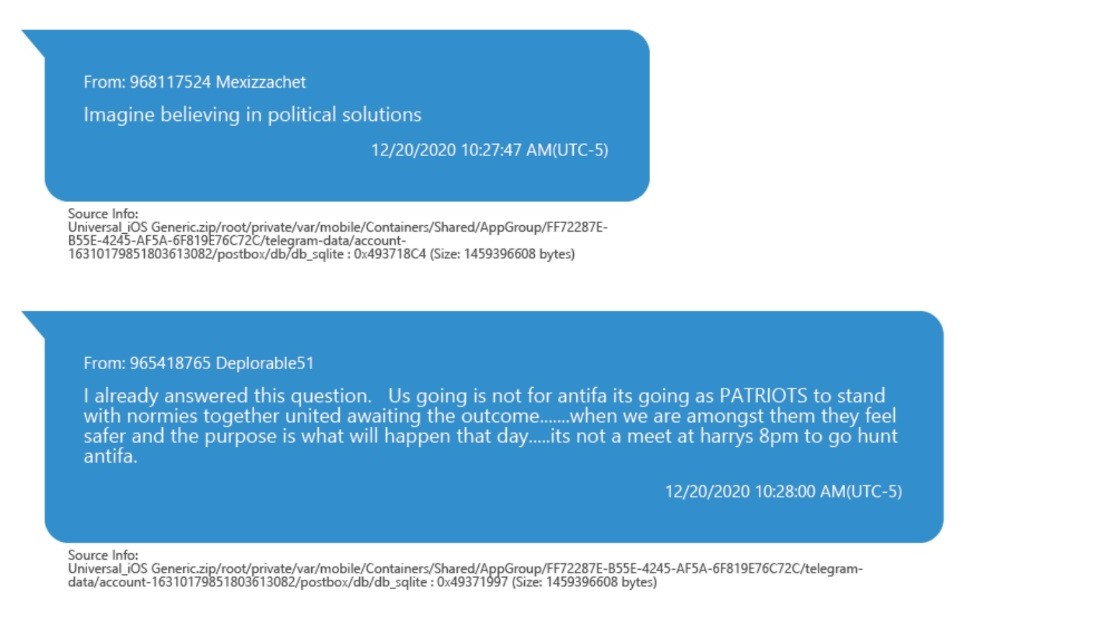

Underpinning the prosecution’s charges is its “tools theory,” which argues that Proud Boys activated their conspiracy to stop proceedings by relying on fellow Proud Boys and “normies” or average protesters alike, in large numbers to aid them, wittingly or not, on Jan. 6.

To that end, prosecutors showed Pezzola video from outside of the Capitol near the Peace Monument. Pezzola testified that he heard a “ruckus” near that area while he was near a line of food trucks. He went off to investigate. It just so happened that when he arrived, barriers were knocked over already, he said.

Kenerson pointed out in footage from the first breach near the Peace Monument that quite “fortuitously” Pezzola appeared at the breach with a Proud Boy from New York right behind him identified as “Hooks.” Hooks was grabbing onto Pezzola as they flowed past police. But Hooks wasn’t with him at the food trucks.

It was a “contained area,” Pezzola said, adding that he was bound to run into somebody he knew.

When New York Proud Boy William Pepe was seen pulling down barricades in video footage and Kenerson started to ask about it, Pezzola deflected immediately to invoking a highly-favored conspiracy theory that it was rioter and former Oath Keeper Ray Epps who told him and others to breach the barriers and go inside the Capitol.

Pezzola then suggested to jurors that Epps was a government informant.

“Mr. Pezzola, you have absolutely no evidence that Ray Epps is a government informant, do you?” Kenerson said.

“I’ve seen no evidence he isn’t,” Pezzola shot back.

There was plenty of evidence of his fellow Proud Boys “bumping into” Pezzola on the 6th at critical times, however.

Like when Pezzola was first approaching the scaffolding, he identified himself in a series of frames from this area and then identified fellow Proud Boys William Pepe, Art Lashone (who he came to D.C. with) and again, “Hooks” and other Proud Boys. After he left the Capitol, he would see Greene again at his hotel, he said, and another Proud Boy identified in court as “Ronie.” When someone asked whether “Ronie” had bear-sprayed a police officer, Pezzola couldn’t say whether he recalled the conversation. He also couldn’t remember what he thought or said when Jeremy Bertino messaged Proud Boys around this time either to tell them they “should have gone further.”

Pezzola’s temper grew most hot when Kenerson grilled him about his reasons for joining the Proud Boys. Where a day before Pezzola had smiled sheepishly and even laughed as he remarked that at 43 years old, he may have been “too old” to be a Proud Boy when he joined, he was downright surly when Kenerson asked him about his convictions that a “civil war was imminent” in the weeks before Jan. 6.

It was a fact that the “other side” was trying to destroy the nation, Pezzola said.

He and his way of life were under daily attack, he said.

In a letter found in his property after his arrest, Pezzola once wrote at length about his hopes and fears, and his anxieties of a takeover of America by “radical socialists” or communists. Prosecutors say the letter was one Pezzola intended to submit to the Proud Boys when applying to join the organization. This was sometimes a requirement for prospects to the organization in late 2020.

“You wanted to stand first on line to protect those you love and what you stand for?” the prosecutor asked.

Angry and defensive, Pezzola testified: “That’s correct and that’s in line with standing against this corrupt trial with your fake charges.”

He called the trial “fake” at another point too when Kenerson brought up social media posts Pezzola had upvoted or liked, including those from Tarrio and others, like one from Proud Boy Jeremy Bertino who said if the government wanted to declare war on the American people, they could have it.

Pezzola boiled over.

“At this point, if I didn’t have a case, I would probably bring up things like this too,” he sniped.

Kenerson nodded passively and brought up a photo of Pezzola on the ground appearing to wrestle a riot shield away from an officer.

“So is this fake evidence to you?” he said.

“I say you interpret it fakely… this is a phony trial because of the way you’re trying to push it off,” Pezzola said.

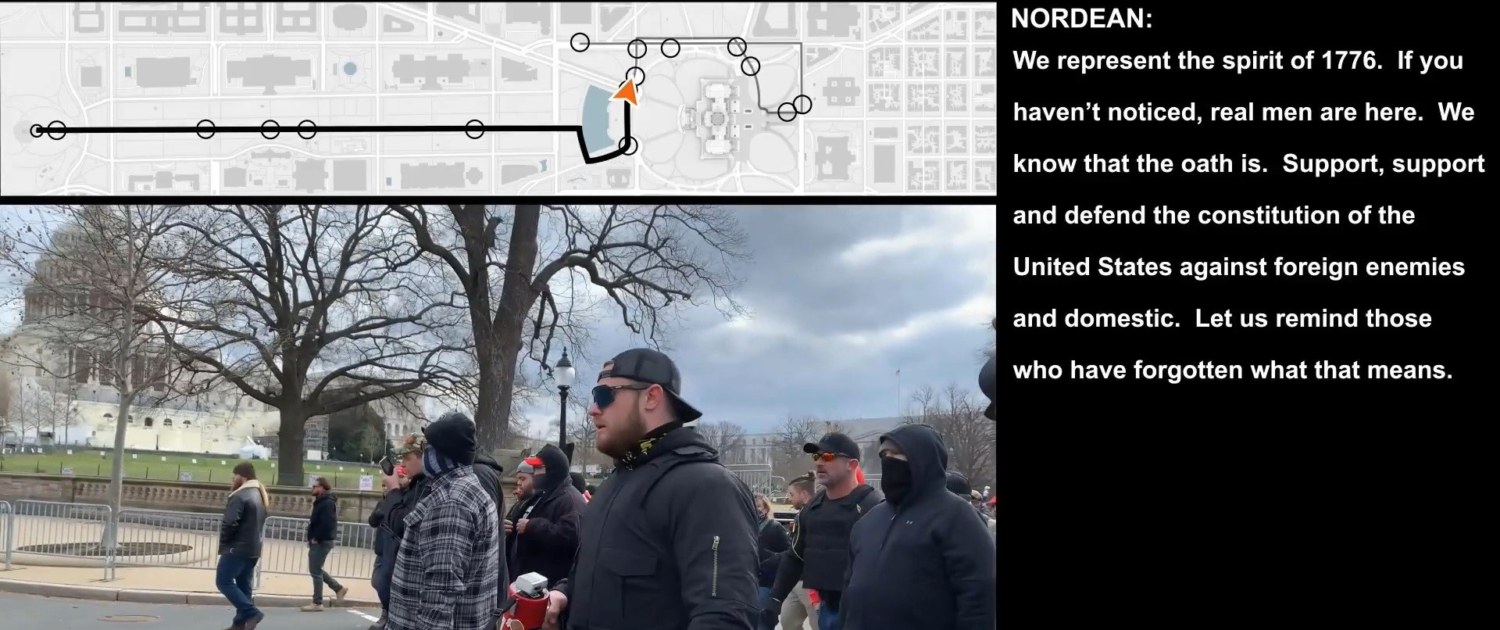

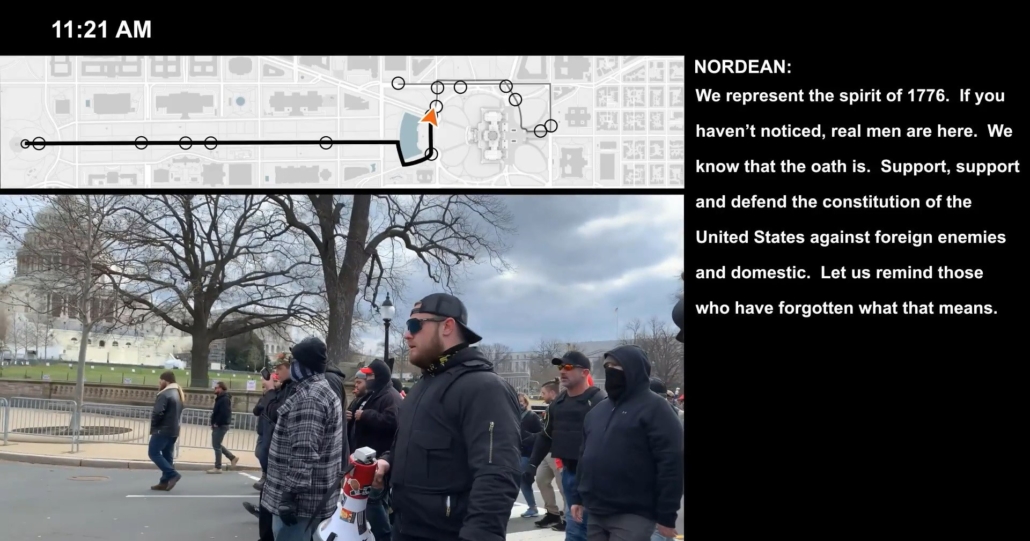

Like Rehl, Pezzola denied there was any “plan” on Jan. 6. Maybe they planned to storm the liquor store, he said, but that was it. Otherwise, when he got to D.C. on the 5th, he had no idea what to expect. He wanted to hear Trump speak. On the morning of the 6th, Pezzola said at first he didn’t know who was in charge. It was a “mishmash” of people, he testified initially. Then he said he assumed his now co-defendant Ethan Nordean was in charge because he held a megaphone. Then he said when they started marching to the Capitol, he knew that whoever was in front was leading the group. Extensive video footage played for the jury has shown Nordean and Biggs and Rehl were always at the front of the marching group with Nordean and Biggs specifically commanding the marching group consisting of dozens of Proud Boys to stop or go.

With yet more of his machismo to display, Pezzola finally said Nordean was in charge of the group.

But “not of me,” he said.

He was in control of himself.

At trial, prosecutors also worked to pick apart whatever credibility Pezzola may have lent to his testimony by bringing out details about his lies to the FBI in the early days following his arrest.

In March 2021, while he was incarcerated, Pezzola claimed that he witnessed—firsthand—his co-defendant Joe Biggs and another man, Ryan Samsel, speak to each other moments before the very first breach of the Capitol. Pezzola told the FBI he saw Biggs flash a gun—a 9MM Beretta—and then he said Biggs told Samsel he better “defend his manhood” by plowing past police to prove he wasn’t antifa.

In court, Pezzola testified that he lied about this episode to the FBI at least twice because he thought it would improve his conditions at the jail where he was being held before this trial began. Video footage from the 6th shows Samsel and Biggs speaking but it has not yet been made clear what Samsel said to Biggs in that moment or vice versa. Samsel goes on trial later this summer.

Pezzola said Samsel was detained in the jail cell next to him initially, and told him this story. Right away Pezzola said he knew it was fake but he nonetheless saw the story as a one-way ticket out of solitary confinement or to receiving his medication he was cut off from or for better “soy free” food that he wasn’t allergic to. He was eventually moved.

Pezzola also told the FBI that when he was at the Peace Circle, he saw a group of Proud Boys harassing a young boy wearing a Black Lives Matter shirt and that he saw Samsel defend the boy and that later, Pezzola even escorted the boy away from the scene. All of that was untrue, all of it a lie. But admitting that it was a lie specifically more than once or twice in court was a visible struggle for Pezzola. He time and again met Kenerson’s questions about the veracity of his statements to the FBI with the retort: “I wasn’t there” instead of “that’s not true” or “I lied.”

Though Pezzola testified that he believed the lie about Biggs is what ultimately got him moved into better conditions, Kenerson pointed out how self-serving Pezzola had been. He only got a hand up by falsely incriminating Joe Biggs.

Pezzola seemed offended by the suggestion. Where loyalty to the Proud Boys was often just under or at the surface of his testimony, and he proudly proclaimed that he had refused to cooperate with the DOJ or take a plea deal, two years ago Pezzola seemed to sing a different tune.

His attorney at the time, Jonathan Zucker, appeared to express interest in a plea agreement for Pezzola, saying that the father of two teenage girls was “consumed with guilt” and wanted to “disavow and seek to sever any relationship and involvement in future activities of the Proud Boys or similar groups.”