I started reading the Combined IG Report on the Marathon attack (including the DOJ, CIA, DHS, and Intelligence Community IGs, but not NSA). And the whole thing looked so bogus from the start, I figured a working thread was in order.

One thing to remember here: we’ve only got a 32-page summary that includes 5 pages of agency (but not CIA) response and a title page. We’re getting a mere fraction of the 168-page report.

To make things worse, some things are redacted that aren’t even classified, they’re just sensitive.

Redactions in this document are the result of classification and sensitivity designations we received from agencies and departments that provided information to the OIGs for this review. As to several of these classification and sensitivity designations, the OIGs disagreed with the bases asserted. We are requesting that the relevant entities reconsider those designations so that we can unredact those portions and make this information available to the public.

(PDF 2) Several things in this passage:

Law enforcement officials identified brothers Tamerlan and Dzhokhar Tsarnaev as primary suspects in the bombings. After an extensive search for the then unidentified suspects, law enforcement officials encountered Tamerlan and Dzhokhar Tsarnaev in Watertown, Massachusetts. Tamerlan Tsarnaev was shot during the encounter and was pronounced dead shortly thereafter.

First, they don’t say what law enforcement officials IDed the brothers. That sentence precedes one which claims there were “unidentified suspects,” which suggests they had suspicions before they were “IDed.” The word “encountered” is awfully suspicious, given that explanations of how the shootout in Watertown happened have been contradictory. And note they don’t say whether Tamerlan died immediately or not–again, an issue about which there’s some contention.

(PDF 2) Note they tell us Anzor’s ethnicity, but not his wife’s (who is more central to this narrative)?

(PDF 2) The report dodges legitimate questions about why the family got refugee status by referring only to “an immigration benefit.” Given reports the uncle had ties to the CIA, that benefit may be more than a simple asylum request.

(PDF 3) Note that, after having previously said the brothers were ID’ed by LE, they now specify FBI [Actually, I think that’s wrong: this is still ambiguous about who IDed them]. But the timing is crazy: it says FBI reviewed its records by April 19, but never says when they were IDed, and doesn’t say whether they were reviewed during a period of suspicion.

By April 19, 2013, after the Tsarnaev brothers were identified as suspects in the bombings, the FBI reviewed its records and determined that in early 2011 it had received lead information from the FSB about Tamerlan Tsarnaev, had conducted an assessment of him, and had closed the assessment after finding no link or “nexus” to terrorism.

(PDF 4) This seems very broad. I wonder what they’re including? Online communications?

As a result, the scope of this review included not only information that was in the possession of the U.S. government prior to the bombings, but also information that existed during that time and that the federal government reasonably could have been expected to have known before the bombings.

(PDF 4) This passage and footnote are huge dodges, making the entire report meaningless.

We carefully tailored our requests for information and interviews to focus on information available before the bombings and, where appropriate, coordinated with the U.S. Attorney’s Office conducting the prosecution of alleged bomber Dzhokhar Tsarnaev.1

1 The initial lead information from the FSB in March 2011 focused on Tamerlan Tsarnaev, and to a lesser extent his mother Zubeidat Tsarnaeva. Accordingly, the FBI and other agencies did not investigate Dzhokhar Tsarnaev’s possible nexus to terrorism before the bombings, and the OIGs did not review what if any investigative steps could have been taken with respect to Dzhokhar Tsarnaev.

I’ll come back to this. But the indictment lists a number of things that the FBI, in their stings, have found and used to identify easy marks. They did not do so here, with Dzhokhar. Which raises real questions about why they chose not to pursue him when they’ve pursued so many other young men like Dzhokhar?

(PDF 4) Here’s who was included in this review:

We also requested other federal agencies to identify relevant information they may have had prior to the bombings. These agencies included the Department of Defense (including the National Security Agency (NSA)), Department of State, Department of the Treasury, Department of Energy, and the Drug Enforcement Administration.

There has been little discussion of DEA’s likely awareness of the brothers, but it is likely, given that they were dealing drugs with potential ties to organized crime. And NSA, but I harp on that too much. I’m curious what role DOE might have.

(PDF 4) Again, they specify they’re only looking at pre-attack data. Which dodges what they could have collected but didn’t.

Additionally, each OIG conducted or directed its component agencies to conduct database searches to identify relevant pre-bombing information.

(PDF 4-5) As with HHSC’s report, the FBI stalled here.

As described in more detail in the classified report, the DOJ OIG’s access to certain information was significantly delayed at the outset of the review by disagreements with FBI officials over whether certain requests fell outside the scope of the review or could cause harm to the criminal investigation. Only after many months of discussions were these issues resolved, and time that otherwise could have been devoted to completing this review was instead spent on resolving these matters.

(PDF 5) The 12333 passage makes it clear NSA had a big role here. But, again, its IG did not conduct an investigation.

(PDF 6-7) The CIA section is very thin. I assume some stuff is missing.

(PDF 8) Note the importance of NSA’s sharing with FBI here?

Of particular relevance to this review are the relationships between the FBI, CIA, and DHS, as well as the relationship between the FBI and the NSA, and the NCTC’s relationships throughout the Intelligence Community.

(PDF 8) This makes clear that the transcription and birthdate errors were in both FSB warnings; it’s just that CIA didn’t fix the second one.

Importantly, the memorandum included two incorrect dates of birth (October 21, 1987 or 1988) for Tamerlan Tsarnaev, and the English translation used by the FBI transliterated their last names as Tsarnayev and Tsarnayeva, respectively.

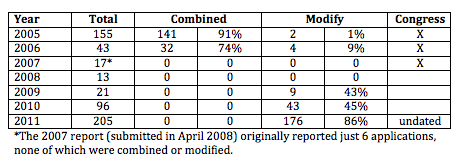

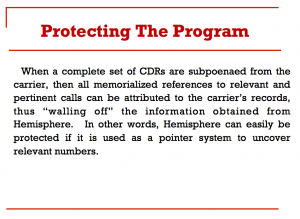

(PDF 10) This passage seems to admit that FBI could have, but did not, search FISA related databases. It also suggests there was a “certain telephone database,” which might include the Hemisphere database, which performs the same function as the NSA claims (falsely) the phone dragnet does. Note, too, that they’ve only checked for the Tsarnaevs in FBI databases. I’ll come back to these databases in a later post.

Additionally, the DOJ OIG determined that the CT Agent did not use every relevant search term known or available at the time to query the FBI systems, including certain telephone databases and databases that include information collected under authority of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA). However, searches of FBI databases conducted at the direction of the DOJ OIG during this review produced little information beyond that identified by the CT Agent during the assessment, with the exception of additional travel-related data for Zubeidat Tsarnaeva.

(PDF 11) Note that the second FBI letter to FSB, dated October 7, 2011, postdated the FSB notice to CIA. But it also comes at a time when Boston area law enforcement were conducting an investigation into the murder of Tamerlan’s best friend. The Waltham murders are not mentioned at all in the unclassified report.

(PDF 12) The IG Report does not tell us the date in September when FSB provided notice to CIA. Given that Tamerlan may have just been or was about to be involved in a grisly murder, I find that omission very notable.

(PDF 12) Note you can be watchlisted without derogatory information. This seems to be because of the exception mentioned in FN 10. But fat lot of good it did in this case. Per the footnote, that exception subsequently got disqualified, though I bet it has been qualified again.

(PDF 12) The IG Report doesn’t even acknowledge there was some other kind of difference between the first and the later watchlist entries as indicated on pp 33-4 of the HHSAC Committee report, which suggests that discussion may be redacted entirely.

(PDF 16) Note that, as happens with all Legal Permanent Residents, Tamerlan was photographed (and fingerprinted) during immigration. I’m surprised there isn’t more discussion of this (though it may be classified). But one big point of this relatively new border protocol is to have recent pictures on hand in case, say, you need to do facial recognition on pictures from a terrorist attack. Were they used?

(PDF 19) Note the big redaction describing intercepted communications. This may simply describe what the Russians had collected, which led to their tip. But I do wonder whether NSA collected its own version, not least because details of the Russian intercept has been widely reported.

(PDF 20) Note that the discussion of Tamerlan’s (remember, Dzhokhar is not included here) computer materials is described solely in terms of what FBI could do. That’s different from what both DHS does (they track public online speech) and NSA. It’s unclear whether they could have found some of this using methods available to them, but the report’s silence on that point is notable.

The FBI’s analysis was based in part on other government agency information showing that Tsarnaev created a YouTube account on August 17, 2012, and began posting the first of several jihadi-themed videos in approximately October 2012. The FBI’s analysis was based in part on open source research and analysis conducted by other U.S. government agencies shortly after the bombings showing that Tsarnaev’s YouTube account was created with the profile name “Tamerlan Tsarnaev.”

[snip]

The DOJ OIG concluded that because another government agency was able to locate Tsarnaev’s YouTube account through open source research shortly after the bombings, the FBI likely would have been able to locate this information through open source research between February 12 and April 15, 2013. The DOJ OIG could not determine whether open source queries prior to that date would have revealed Tsarnaev to be the individual who posted this material.

The passage goes on to report the 7 copies of Inspire on one of the computers used by Tamerlan (again, there’s no mention of Dzhokhar here).

Something they’re not saying, but we know to be true. Had they picked up Inspire either through a 702 upstream search or XKeyscore, they would have had identifiers that could have pegged Tsarnaev’s identity and tied it to all his other identities, regardless of the fact Tamerlan used an alias until February 2013.

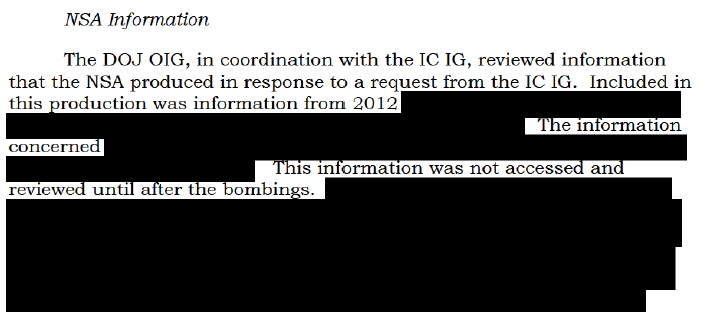

And note the big redaction: NSA had information that dated to 2012, which may well have been the intercepts with Plotnikov.

Finally, note that FBI never turned over most of the information about Tamerlan’s Google accounts. The excuse (as noted above) was the ongoing investigation. But I wonder whether that’s ongoing investigation into the Waltham murder or the Marathon attack.

(PDF 25) Note the discussion of enhancement in the 2nd-to-last bullet. I believe this suggests that transliteration questions are only addressed with this enhancement.

(PDF 25) Note that they at least used to delete US person travel info after 6 months unless it represents terrorism information. This would arise from NCTC’s minimization procedures.

(PDF 32) As noted above, we don’t get John Brennan’s response to this, though he presumably sent one. I suspect that means there are classified recommendations for the Agency and that his response reflects that. While it’s not clear what the foreign target would be in this context (perhaps an investigation of the person to whom Zubeidat was speaking about Tamerlan wanting to join jihad?) but there seems to have been some.

As I noted in my last post, DOJ’s Inspector General recently created a page showing their ongoing investigations. It shows some things not described in Inspector General Michael Horowitz’ last report to Congress.

As I noted in my last post, DOJ’s Inspector General recently created a page showing their ongoing investigations. It shows some things not described in Inspector General Michael Horowitz’ last report to Congress.