Latex Gloves Hiding Evidence of Conspiracies: On the Unknown Adequacy of the January 6 Investigation

Since I’ve acquired new readers with my January 6 coverage and since the financial stress of COVID is abating for many, it seems like a good time to remind people this is not a hobby: it is my day job, and I’d be grateful if you support my work.

Update, 6/2: As this post lays out, Hodgkins’ plea was indeed just a garden variety plea. During the hearing he explained the latex gloves. He carries a First Aid kit around all the time and saw Joshua Black’s plastic bullet wound (though he didn’t know Black and didn’t name him in the hearing) and put gloves on in preparation to provide medical assistance. After Black declined his help, he took the latex gloves off.

On Wednesday, June 2, insurrectionist Paul Allard Hodgkins will plead guilty, becoming just the second of around 450 defendants to publicly plead guilty (particularly given the number of people involved, there may be — and I suspect there are — secret cooperation pleas we don’t know about).

NOTICE OF HEARING as to PAUL ALLARD HODGKINS: A Plea Agreement Hearing is set for 6/2/2021, at 11:00 AM, by video, before Judge Randolph D. Moss. The parties shall use the same link for connecting to the hearing.(kt)

This could be the first of what will be a sea of plea deals, people accepting some lesser prison time while avoiding trial by pleading out. But there’s one detail that suggests it could be more, that suggests Hodgkins might have knowledge that would be sufficiently valuable that the government would give him a cooperation deal, rather than just a plea to limit his prison time.

Hodgkins is one of the people who made it to the Senate floor and started rifling through papers there, which by itself has been a locus of recent investigative interest. But he is an utterly generic rioter, wearing a Trump shirt and carrying a Trump flag. According to an uncontested claim in his arrest affidavit, he told the FBI he traveled to the insurrection from Florida alone, by bus. Because the only challenge he made to his release conditions — to his curfew — was oral, and because the prosecutor in his case hasn’t publicly filed any notice of discovery (which would disclose other kinds of evidence against him), there’s nothing more in his docket to explain who he is or what else he did that day, if anything.

But one thing sticks out about him: before he started rifling through papers in the Senate, he put on latex gloves.

It’s not surprising he had gloves. During the pandemic, after all, latex gloves have been readily available, and I’ve wandered around with gloves in my jacket pocket for weeks. But he did show the operational security to put them on, when all around him people were just digging in either bare-handed or wearing the winter or work gloves they had on because it was a pretty cold day.

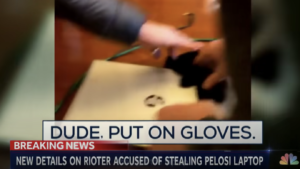

There’s just one other instance I know of where someone at the insurrection showed that kind of operational security (though there is one person identified by online researchers by the blue latex gloves he wore while playing a clear organizational role outside the Capitol). When one of the guys that Riley June Williams was with started to steal Nancy Pelosi’s laptop, Williams admonished him, “dude, put on gloves” and threw black gloves (which may or may not be latex) onto the table for him to use.

There’s no reason to believe there’s a tie (as it happens, Williams had a status hearing last week where her conditions were loosened so she can look for work). There is a cybersecurity prosecutor, Mona Sedky, who is common to both cases, which sometimes indicates a tie, but she is also on cases against defendants who have no imaginable tie to Williams. But Hodgkins exhibited the kind of operational security that, otherwise, only other people who seemed to be operating from some kind of plan exhibited.

My point is not that there’s a tie, but that we don’t know whether there’s something more interesting about Hodgkins, and we might not even learn whether there is on Wednesday, in significant part because if there is one, prosecutors may not want to share that information publicly.

And I think, particularly in the wake of Republicans’ successful filibuster of a January 6 Commission and discussions of whether there will be any real accountability, that’s a useful illustration about the limits of our ability to measure the efficacy of the investigation right now. Paul Hodgkins could be (and probably is) just some Trump supporter who hopped on a bus, or his latex gloves could be the fingerprint of a connection to more organized forces.

With that said, I’d like to talk about what we can say about the investigation so far, and where it might go.

Last week, when I read this problematic and in several areas factually erroneous attempt to describe the attack in military terms, I realized that readers new to my work may not understand what I do.

I cover a range of things, but when I cover a legal case, I cover the legal case as a means to understand what prosecutors are seeing. That’s different than describing the alleged crime itself; particularly given the flood of defendants, I’m not, for example, reading through scraped social media accounts from before the attack to understand what was planned in the semi-open in advance. But reading the filings closely is one way to understand where the criminal investigation might go and the chances it will be successfully prosecuted and if so how broadly the prosecution will reach.

I’m not a lawyer, though I’ve got a pretty decent understanding of the law, especially the national security crimes I’ve covered for 17 years. But my background in corporate documentation consulting and comparative literature (plus the fact that I don’t have an editor demanding a certain genre of writing) means I approach legal cases differently than most other journalists. For the purposes of this post, for example, my academic expertise in narrative theory makes me attuned to how prosecutors are withholding information and focalizing their approach to preserve investigative equities (or, at times, hide real flaws in their cases). Prosecutors are just a special kind of story-teller, and like novelists and directors they package up their stories for specific effects, though criminal law, the genre dictated by court filings, and prohibitions on making accusations outside of criminal charges impose constraints on how they tell their stories.

One of the tools prosecutors use, both in a legal sense and a story-telling one, is conspiracy. The problematic military analysis, linked above, totally misunderstood that part of my work (as have certain Russian denialists looking for a way to attack that doesn’t involve grappling with evidence): when I map out the conspiracies we’re seeing in January 6, I’m not talking about the overarching conspiracy that made it successful, how the entire event was planned. Rather, I’m observing where prosecutors have chosen to use that tool — by charging four separate conspiracies against Proud Boys that prosecutors are sloppily treating as one, and charging (as of yesterday) sixteen members of the Oath Keepers in a single conspiracy — and where they haven’t, yet — for a set of guys who played key roles in breaching the East door and the Senate chamber who armed themselves and traveled together. As that set of guys shows, prosecutors aren’t limited to using conspiracy with organized militias, and I expect we’ll begin to see some other conspiracies charged against other networks of insurrectionists. It’s virtually certain, for example, that we’ll see some conspiracies charged against activists who first organized together in local Trump protests; I expect we’ll see conspiracies charged against other pre-existing networks (like America First or QAnon or even anti-vaxers who used those pre-existing networks to pre-plan their role in the insurrection).

Conspiracies are useful tools for prosecutors for several purposes. For example, a conspiracy charge can change what you need to prove: that the conspiracy was entered into and steps taken, some criminal, to achieve the conspiracy, rather than the underlying crime. It can used to coerce cooperation from co-conspirators and enter evidence at trial in easier fashion. And it’s the best way to hold organizers accountable for the crimes they recruit others to commit.

If Trump, or even his flunkies, are going to be held accountable for January 6, it will almost certainly be through conspiracy charges built up backwards from the activities at the Capitol. I am agnostic on whether they will be, but it’s not as far a reach as some might think. This handy guide to conspiracy law that Elizabeth de la Vega laid out during the Mueller investigation provides a sense of why that is.

Conspiracy Law – Eight Things You Need to Know.

One: Co-conspirators don’t have to explicitly agree to conspire & there doesn’t need to be a written agreement; in fact, they almost never explicitly agree to conspire & it would be nuts to have a written agreement!

Two: Conspiracies can have more than one object- i.e. conspiracy to defraud U.S. and to obstruct justice. The object is the goal. Members could have completely different reasons (motives) for wanting to achieve that goal.

Three: All co-conspirators have to agree on at least one object of the conspiracy.

Four: Co-conspirators can use multiple means to carry out the conspiracy, i.e., releasing stolen emails, collaborating on fraudulent social media ops, laundering campaign contributions.

Five: Co-conspirators don’t have to know precisely what the others are doing, and, in large conspiracies, they rarely do.

Six: Once someone is found to have knowingly joined a conspiracy, he/she is responsible for all acts of other co-conspirators.

Seven: Statements of any co-conspirator made to further the conspiracy may be introduced into evidence against any other co-conspirator.

Eight: Overt Acts taken in furtherance of a conspiracy need not be illegal. A POTUS’ public statement that “Russia is a hoax,” e.g., might not be illegal (or even make any sense), but it could be an overt act in furtherance of a conspiracy to obstruct justice.

We know that Trump and his flunkies shared the goal of the conspiracies that have already been charged: to prevent the certification of the vote. Trump (and some of his flunkies) played a key role in one of the manner and means charged in most of the conspiracies: To use social media to recruit as many people as possible to get to DC. Arguably, Mike Flynn played another role, in setting the expectation of insurrection.

What’s currently missing is proof (in court filings, as opposed to the public record) that people conspiring directly with Trump were also conspiring directly with those who stormed the Capitol. But we know the White House had contact with some of the conspirators. We know that organizers like Ali Alexander and Alex Jones likewise had ties to both conspirators and Trump’s flunkies (an Alex Jones producer has already been arrested). We know that Flynn had other ties to QAnon (which is why I’ll be interested if the government ever claims QAnon had some more focused direction with respect to January 6). Most of all, Roger Stone has abundant ties with people already charged in the militia conspiracies, and was at the same location as some of the Oath Keepers before they raced to the Capitol in golf carts to join the mob. If Trump or his flunkies are held accountable, I suspect it will go through conspiracies hatched in Florida, and the overlap right now between the Oath Keeper and Proud Boys conspiracies are in Floridians Kelly Meggs and Joe Biggs. But if they are held accountable, it will take time. It’s hard to remember given the daily flow of new defendants, but complex conspiracies don’t get charged in four months, and it will take some interim arrests and a number of cooperating witnesses to get to the top levels of the January 6 conspirators, if it ever happens.

This post, which is meant to be read in tandem with this one, assesses developments in the last week or so in the Oath Keepers conspiracy case.