Something puzzles me about both Josh Schulte trials (as noted yesterday, the jury found Schulte guilty of al charges against him yesterday).

In both, the government introduced a passage from his prison notebooks advocating the use of the tools he has now been found guilty of sharing with WikiLeaks in an attack similar to NotPetya. [This is the version of this exhibit from his first trial.]

Vault 7 contains numerous zero days and malware that could be [easily] deployed repurposed and released onto the world in a devastating fashion that would make NotPetya look like Child’s play.

Neither time, however, did prosecutors explain the implications of this passage, which proved both knowledge of the non-public files released to WikiLeaks and a desire that they would be used, possibly by Russia, as a weapon.

Here’s how AUSA Sidhardha Kamaraju walked FBI Agent Evan Schlessinger through explaining it on February 26, 2020, in the first trial.

Q. Let’s look at the last paragraph there.

A. “Vault 7 contains numerous zero days and malware that could easily be deployed, repurposed, and released on to the world in a devastating fashion that would make NotPetya look like child’s play.”

Q. Do you know what NotPetya is?

A. Yes, generally.

Q. What is it?

A. It is a version of Russian malware.

Here’s how AUSA David Denton walked Agent Shlessinger through that same exact script this June 30 in the second trial.

Q. And the next paragraph, please.

A. “Vault 7 contains numerous zero days and malware that could easily be deployed,” struck through “repurposed and released onto the world in a devastating fashion that would make NotPetya look like child’s play.”

Q. Sir, do you know what NotPetya is?

A. Yes, generally.

Q. Generally, what is a reference to?

A. Russian malware.

The placid treatment of that passage was all the more striking in this second trial because it came shortly after Schulte had gone on, at length, mocking the claim from jail informant Carlos Betances that Schulte had expressed some desire for Russia’s help to do what he wanted to do, which in context (though Betances wouldn’t know it) would be to launch an information war.

Q. OK. Next, you testified on direct that I told you the Russians would have to help me for the work I was doing, right?

A. Yes, correct.

Q. OK. So the Russians were going to send paratroopers into New York and break me out of MCC?

MR. LOCKARD: Objection.

THE COURT: Sustained.

BY MR. SCHULTE: Q. What is your understanding of how the Russians were going to help?

A. No, I don’t know how they were going to help you. You were the one who knew that.

Q. What work was I doing for Russia?

A. I don’t know what kind of work you were doing for Russia, but I know you were spending long periods of time in your cell with the phones.

Q. OK.

A. With a sheet covering you.

Q. OK. But only Omar ever spoke about Russia, correct?

A. No. You spoke about Russia.

Q. Your testimony is you never learned anything about Omar and Russian oligarchs?

A. No.

Denton could easily have had Schlessinger point out that wanting to get a CIA tool repurposed in Russian malware just like the Russians had integrated stolen NSA tools to use in a malware attack of unprecedented scope would be pretty compelling malicious cooperation with Russia. It would have made Schulte’s mockery with Betances very costly. But Denton did not do that.

In fact, the government entirely left this theory of information war out of Schulte’s trial. In his closing argument for the second trial, for example, Michael Lockard explicitly said that Schulte’s weapon was to leak classified information, not to launch cyberattacks.

Mr. Schulte goes on to make it even more clear. He says essentially it is the same as taking a soldier in the military, handing him a rifle, and then begin beating him senseless to test his loyalty and see if you end up getting shot in the foot or not. It just isn’t smart.

Now, Mr. Schulte is not a soldier in the military, he is a former CIA officer and he doesn’t have a rifle. He has classified information. That is his bullet.

To be sure, that’s dictated by the charges against Schulte. Lockard was trying to prove that Schulte developed malicious plans to leak classified information, not that he developed malicious plans to unleash a global cyberattack that would shut down ports in the United States. But that’s part of my point: The NotPetya reference was superfluous to the charges against Schulte except to prove maliciousness they didn’t use it for.

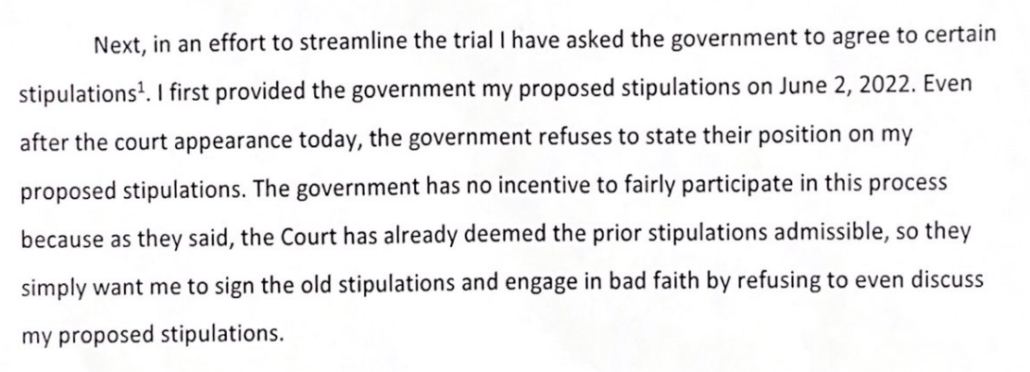

I may return to this puzzle in a future post. For now, though, I want to use it as background to explain how, that very same day that prosecutors raised Schulte’s alleged plan to get CIA hacking tools used to launch a global malware attack, Schulte got Judge Jesse Furman to open a document in Internet Explorer.

One of the challenges presented when a computer hacker like Schulte represents himself (pro se) is how to equip him to prepare a defense without providing the tools he can use to launch an information war. It’s a real challenge, but also one that Schulte exploited.

In one such instance, in February, Schulte argued the two MDC law library desktops available to him did not allow him to prepare his defense, and so he needed a DVD drive to transfer files including “other binary files,” the kind of thing that might include malware.

Neither of these two computers suffices for writing and printing motions, letters, and other documents. The government proposes no solution — they essentially assert I have no right to access and use a computer to defend myself in this justice system.

I require an electronic transfer system; printing alone will not suffice, because I cannot print video demonstratives I’ve created for use at trial; I cannot print forensics, forensic artifacts, and other binary files that would ultimately be tens of thousands of useless printed pages. I need a way to transfer my notes, documents, motion drafts, demonstrative videos, technical research, analysis, and countless other documents to my standby counsel, forensic expert, and for filing in this court.

The government had told Schulte on January 21 that he could not have a replacement DVD drive that his standby counsel had provided in January because it had write-capabilities; as they noted in March, not having such a drive was not preventing him from filing a blizzard of court filings. Ultimately, in March, the government got Schulte to let them access the laptop to add a printer driver to his discovery laptop. Schulte renewed his request for a write-capable DVD, though, in April.

Schulte continued to complain about his access to the law library for months, sometimes with merit, and other times (such as when he objected to the meal times associated with his choice to fast during Ramadan) not.

The continued issues, though, and Schulte’s claims of retaliation by prison staffers, are why I was so surprised that when, on June 1, Sabrina Shroff reported that a guard had broken Schulte’s discovery laptop by dropping it just weeks before trial, she didn’t ask for any intervention from Judge Furman. Note, she attributes her understanding of what happened to the laptop to Schulte’s parents (who could only have learned that from Schulte) and the prison attorney (who may have learned of it via Schulte as well). In response, as Shroff had tried to do with the write-capable DVD, she was just going to get him a new laptop.

We write to inform the Court that a guard at the MDC accidently dropped Mr. Schulte’s laptop today, breaking it. Because the computer no longer functions, Mr. Schulte is unable to access or print anything from the laptop, including the legal papers due this week. The defense team was first notified of the incident by Mr. Schulte’s parents early this afternoon. It was later confirmed in an email from BOP staff Attorney Irene Chan, who stated in pertinent part: “I just called the housing unit and can confirm that his laptop is broken. It was an unfortunate incident where it was accidentally dropped.”

Given the June 13, 2022 trial date, we have ordered him a new computer, and the BOP, government, and defense team are working to resolve this matter as quickly as possible. We do not seek any relief from the Court at this time.

Only, as I previously noted, that’s not what happened to the laptop, at all. When DOJ’s tech people examined the laptop, it just needed to be charged. As they were assessing it, though, they discovered he had a 15GB encrypted partition on the laptop and had been trying to use wireless capabilities.

First, with respect to the defendant’s discovery laptop, which he reported to be inoperable as of June 1, 2022 (D.E. 838), the laptop was operational and returned to Mr. Schulte by the end of the day on June 3, 2022. Mr. Schulte brought the laptop to the courthouse on the morning of June 3 and it was provided to the U.S. Attorney’s Office information technology staff in the early afternoon. It appears that the laptop’s charger was not working and, after being charged with one of the Office’s power cords, the laptop could be turned on and booted. IT staff discovered, however, that the user login for the laptop BIOS1 had been changed. IT staff was able to log in to the laptop using an administrator BIOS account and a Windows login password provided by the defendant. IT staff also discovery an encrypted 15-gigabyte partition on the defendant’s hard drive. The laptop was returned to Mr. Schulte, who confirmed that he was able to log in to the laptop and access his files, along with a replacement power cord. Mr. Schulte was admonished about electronic security requirements, that he is not permitted to enable or use any wireless capabilities on the laptop, and that attempting to do so may result in the laptop being confiscated and other consequences. Mr. Schulte returned to the MDC with the laptop.

1 The BIOS is firmware used to provide runtime services for operating systems and programs and to perform hardware initialization during the booting process. The BIOS settings can determine, for example, whether external ports and wireless capabilities are enabled or disabled.

This had all the markings of a hacker — someone who had once envisioned launching a cyberattack as part of his information war from jail — trying to prepare just such an attack.

Weeks later, during the trial, the government intimated that they might punish Schulte for that stunt, but were just trying to get through trial.

We have not taken any action in response to that, because we’re in the middle of trial and we’re loath to do things that would disrupt the trial at this point.

Along the way, though, Schulte’s laptop access continued to grow — for perfectly justifiable reasons tied to the trial, but which appears to have resulted in the discovery laptop (the one with the encrypted partition that he had apparently tried to access WiFi on) being in the same place as a second exhibit laptop, perhaps the very laptop originally intended to replace the one that wasn’t really broken at all. On June 13, Judge Furman ordered the Marshals to let Schulte keep his laptop at breaks. On June 15, Schulte got Furman to order the Marshals to let him use his second laptop, “just like the discovery laptop.”

MR. SCHULTE: OK. So the first thing is I think the marshals just need permission or authorization from you for me to be able to use the second laptop for my exhibits.

THE COURT: Use in the courtroom?

MR. SCHULTE: Yeah, be able to access and use it likeI use the other. I think there was court order for me to be able to use this laptop so they need authorization from you for me to use the second laptop.

THE COURT: And the second laptop is something that standby counsel procured? What is it?

MR. SCHULTE: Yes.

THE COURT: Any objection, Mr. Denton? Any concerns?

MR. DENTON: I think as long as it is something that’s used just here in the courtroom, that’s fine, your Honor. I think to the extent that it was going with the defendant anywhere else other than the courtroom, we would want to make sure that we applied the same security procedures that were applied to his original laptop.

THE COURT: Is it just to be used in this courtroom?

MR. SCHULTE: Yes. That’s correct. It is being locked, I think, in the FBI marshal’s room by the SCIF.

On June 17, Schulte asked Furman to issue a specific order to MDC to ensure he’d be able to “go to the law library and access the laptop.” Again, these are generally understandable accommodations for a defendant going pro se. But they may have placed his discovery laptop (normally used in MDC in Brooklyn) in close proximity to his exhibit laptop used outside of a SCIF in Manhattan.

With that in the background, on June 24, prosecutors described that just days earlier, Schulte had provided them code he wanted to introduce as an exhibit at trial. There were evidentiary problems — this was a defendant representing himself trying to introduce his own writing without taking the stand — but the real issue was his admission he was writing (very rudimentary) code on his laptop. As part of that explanation, the government also claimed that MDC had found Schulte tampering with the law library computer.

The third, however, and most sort of problematic category are the items that were marked as defense exhibits 1210 and 1211, which is code and then a compiled executable program of that code that appear to have been written by the defendant. That raises an evidentiary concern in the sense that those are essentially his own statements, which he’s not entitled to offer but, separately, to us, raises a substantial security concern of how the defendant was able to, first, write but, more significantly, compile code into an executable program on his laptop.

You know, your Honor, we have accepted a continuing expansion of the defendant’s use of a laptop that was originally provided for the purpose of reviewing discovery, but to us, this is really a bridge too far in terms of security concerns, particularly in light of the issues uncovered during the last issue with his laptop and the concerns that the MDC has raised to us about tampering with the law library computer. We have not taken any action in response to that, because we’re in the middle of trial and we’re loath to do things that would disrupt the trial at this point. The fact that defendant is compiling executable code on his laptop raises a substantial concern for us separate from the evidentiary objections we have to its introduction.

THE COURT: OK. Maybe this is better addressed to Mr. Schulte, but I don’t even understand what the third category would be offered for, how it would be offered, what it would be offered for.

MR. DENTON: As best we can tell, it is a program to change the time stamps on a file, which I suppose would be introduced to show that such a thing is possible. I don’t know. We were only provided with it on Tuesday. Again, we think there are obvious issues with its admissibility separate and apart from its relevance, but like I said, for us, it also raises the security concern that we wanted to bring to the Court’s attention.

[snip]

MR. SCHULTE: But for the code, the government produced lots of source code in discovery, and this specific file is, like, ten, ten lines of source code as well as —

THE COURT: Where does it come from? Did you write it?

MR. SCHULTE: Yes, I wrote it. That’s correct.

Schulte didn’t end up introducing the script he wrote. Instead, he asked forensics expert Patrick Leedom if he knew that Schulte had used the “touch” command in malware to alter file times.

Q. Do you know about the Linux touch command?

A. Yes.

Q. This command can be used to change file times, right?

A. Yes, it can.

Q. That includes access times, right?

A. Yes.

Q. And from reviewing my workstation, you know that I developed Linux malware tools for the CIA, right?

A. I know you worked on a few tools. I don’t know if they were Linux-specific or not, but —

Q. And you knew from that that I wrote malware that specifically used the touch command to change file times, right?

In the end, then, it turned out to be just one of many instances during the trial where Schulte raised the various kinds of malware he had written to hide his tracks, infect laptops, and jump air gaps, instances that appeared amidst testimony — from that same jail informant, Carlos Betonces — that Schulte had planned to launch some kind of key event in his information war from the (MCC) law library.

Q. That we — you testified that we were going to do something really big and needed to go to the law library, right?

A. You were paying $200 to my friend named Flaco to go to the library, yes.

Q. I paid someone money?

A. No. They were paying. And Flaco refused to take it downstairs. And the only option left was that they had to go down and take it themselves.

Q. OK. So Omar offered to pay money for Flaco to take some phone down, right?

A. That’s not how Flaco told me. That’s not the way Flaco described it. He said that both of them were offering him money.

Q. All right. But there were cameras in the law library, correct?

THE INTERPRETER: I’m sorry. Can you repeat the question?

Q. There were cameras in the law library, correct?

A. I don’t know.

Q. OK. But your testimony on direct was that me and Omar needed to send some information from the phone, right?

A. Let me explain it to you again. Not information. It’s that you had to do something in the, in the library. That’s what I testified about.

Q. OK. What did I have to do in the law library, according to you?

A. Well, you’re very smart. You must know the question. There was something down there that you wanted to use that you couldn’t use upstairs.

Q. OK. You also testified something about a USB drive, right?

A. Yes.

Q. You testified, I believe, that me and Omar wanted a USB device, right?

A. Yeah. You asked me all the time when the drive was going to arrive. When was it coming? When was it coming?

Q. OK. But there were already USB hard drives given to prisoners in the prison, right?

A. Not to my understanding.

Q. You don’t — you never received or saw anyone using a USB drive with their discovery on it?

A. No, because I — no, I hardly ever went down to the law library.

Q. All right. And then you said, you testified that you slipped a note under the guard’s door?

A. Yes.

Q. And that was about, you said something was going to happen in the law library, right?

THE INTERPRETER: Could you repeat the question, please?

MR. SCHULTE: Yes.

Q. You said that the note said something was going to happen in the law library, right?

A. Yes.

Which finally brings us to the Internet Explorer reference. During his cross-examination of FBI Agent Schlessinger on June 30, Schulte attempted to introduce the return from the warrant FBI served on WordPress after discovering Schulte was using the platform to blog from jail. The government objected, which led to an evidentiary discussion after the jury left for the weekend. The evidentiary discussion pertained to how to introduce the exhibit — which was basically his narrative attacking the criminal justice system — without also disclosing the child porn charges against Schulte referenced within them.

Schulte won that discussion. On the next trial day, July 6, Furman ruled for Schulte, and Schulte said he’d just put a document that redacted the references to his chid porn and sexual assault charges on a CD to share with the government.

MR. SCHULTE: Yes. I just — if I can get the blank CD from them or something I can just give it to them and they can review it.

But back on June 30, during the evidentiary discussion, Judge Furman suggested that the 80- or 90-page document that the government was looking at was something different than the file he was looking at.

That was surprising to Furman.

So was the fact that his version of the document opened in Internet Explorer.

MR. DENTON: Your Honor, on Exhibit 410 we recognize the Court has reserved judgment on that. I want to put sort of a fourth version in the hopper. At least in the version we are looking at, it is a 94-page 35000-word document. To the extent that the only thing the Court deems admissible is sort of the fact that there were postings that did not contain NDI, we would think it might be more appropriate to stipulate to that fact rather than put, essentially, a giant manifesto in evidence not for the truth. So I want to put that option out there given the scope of the document.

[snip]

MR. DENTON: Understood, your Honor. I think at that point, even if we get past the hearsay and the not for the truth problems, then there is a sort of looming 403 problem in the sense that it is a massive document that is essentially an manifesto offered for a comparatively small point. I think at that point it is risk of confusing the jury and potentially inflaming them if people decide to sit down and to read his entire screed, it significantly outweighs the fairly limited value it serves. But, we recognize the Court has reserved on this so I don’t need to belabor the point now.

THE COURT: Unless I am looking at something different, what I opened as Defendant’s Exhibit 410 — it opened for me in Internet Explorer, for some reason and I didn’t even think Internet Explorer existed anymore — and it does not appear to be 84 pages. So, I don’t even know if I am looking at what is being offered or not. But, let me add another option, which is if the government identifies any particular content in here that it thinks should be excluded under 403, then you are certainly welcome to make that proposal as well in the event that I do decide that it should come in in more or less its entirety with the child porn redacted. And if you think that there is something else that should be redacted pursuant to 403, I will consider that. All right?

MR. DENTON: We will make sure we are looking at the same thing and take a look at it over the weekend, your Honor.

To be clear: The reason this opened in IE for Furman is almost certainly that the document was old — it would date to October 2018 — and came in a proprietary form that Furman’s computer didn’t recognize. So for some reason, his computer opened it in IE.

That said, it’s not clear that the discrepancy on the page numbers in the file was ever addressed. Schulte just spoke to one of the prosecutors and they agreed on how it would be introduced.

And if a developer who had worked on malware in 2016 wanted an infection vector, IE might be one he’d pick. That’s because Microsoft stopped supporting older versions of IE in 2016, the year Schulte left the CIA. And WordPress itself was a ripe target for hacking in 2018. Schulte himself might relish using a Microsoft vector because the expert in the trial, Leedom, has moved onto Microsoft since working as a consultant to the FBI.

I have no idea how alarmed to be about all this. The opinions from experts I’ve asked have ranged from “dated file” to “he’d have to be lucky” to “unlikely but potentially terrifying” to “no no no no!” And Schulte is the kind of guy who lets grudges fester so badly that avenging the grudge becomes more important than all else.

So I wanted to put this out there so smarter people can access the documents directly — and perhaps so technical staff from the courthouse can try to figure out why that document opened in Internet Explorer.

Note: As it did with the first trial, Calyx Institute made the transcripts available. This time, however, they were funded by Germany’s Wau Holland Foundation. WHF board member Andy Müller-Maguhn has been named in WikiLeaks operations and was in the US during some of the rough period when Schulte is alleged to have leaked these documents.