Right Wing Propaganda Fail: Julie Kelly’s Troubles with Ten and Two

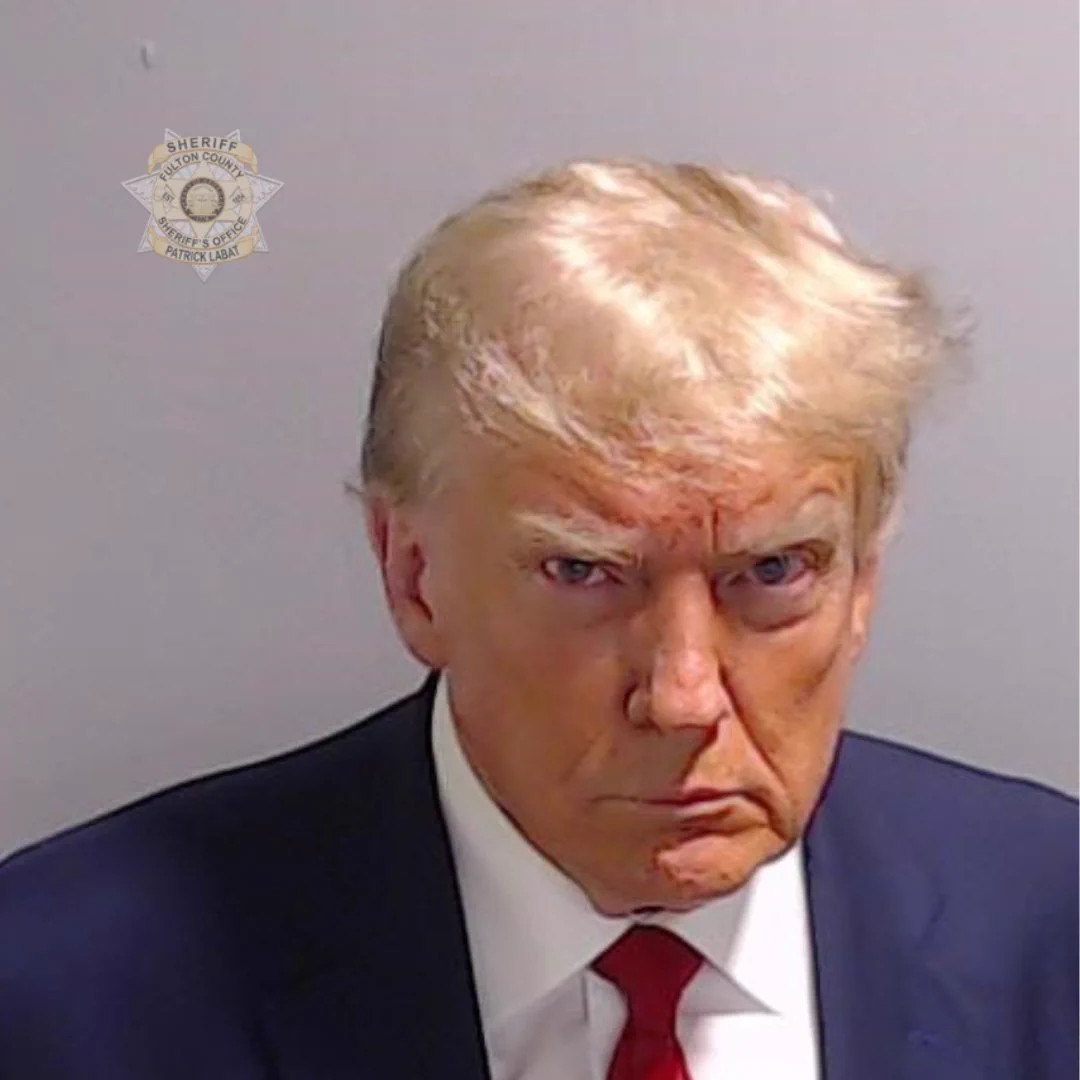

As I laid out in this post, Julie Kelly is an important right wing propagandist who has ginned up quite a lot of attention from accused fraudsters for her willingness to lie about Jan6ers and Donald Trump. Her propaganda may have given Aileen Cannon cover to delay trial for Trump’s alleged unlawful retention of National Defense Information, including a nuclear document.

I say she’s a propagandist willing to lie based on an extended discussion we had in 2021 about January 6ers charged with assaulting cops (at a minimum, 18 USC 111(a)). She reviewed my (incomplete) list, challenged a number of people on it — for example, people who had been charged with 18 USC 111 via complaint but charged with something else, like 18 USC 231, upon indictment. There were 112 people on the list. Nevertheless, Julie never retracted her false claim — a foundational one in Jan6 hagiography — that fewer than 100 Jan6ers had been charged with assaulting cops. Having been presented with proof she was wrong, she simply continued to tell the same lie, downplaying the alleged (and since then, adjudicated) violence of the Jan6ers she was claiming were peaceful protestors.

Because trolls keep pointing to her latest work, in which she accused the FBI of doctoring the initial photo released from the Mar-a-Lago search, I wanted to point out how Julie continues to struggle with numbers, this time the difference between ten and two, and as a result has badly deceived all those poor trolls.

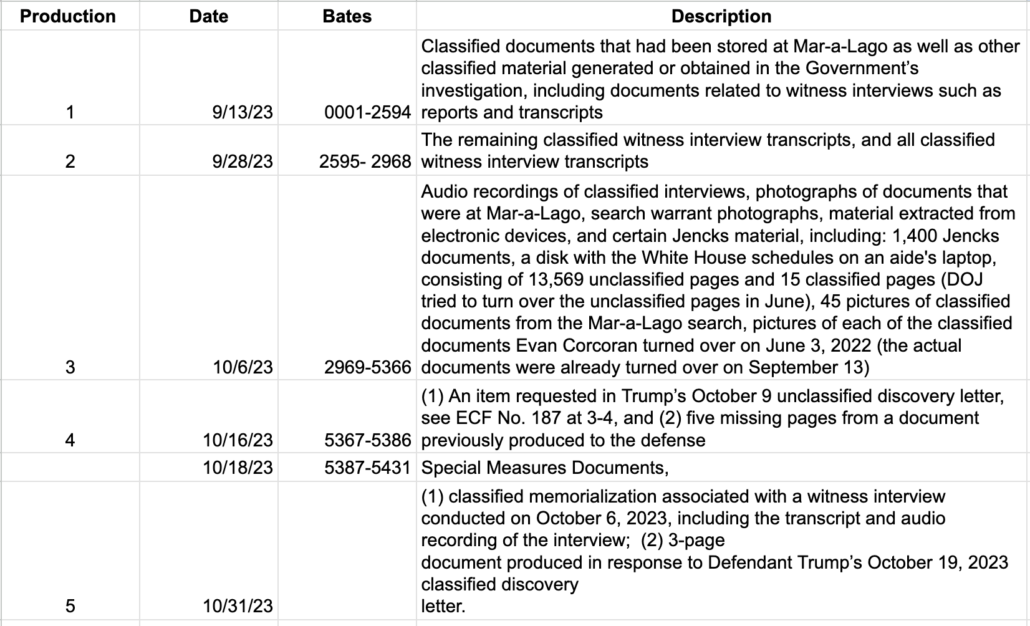

She claims that Jay Bratt lied in his description of what the FBI found at Mar-a-Lago, in which he referred to the famous photo from the search, which Bratt specifically described as a photo of documents and classified cover sheets found in a container seized in Trump’s office.

Jay Bratt, who was the lead DOJ prosecutor on the investigation at the time and now is assigned to Smith’s team, described the photo this way in his August 30, 2022 response to Trump’s special master lawsuit:

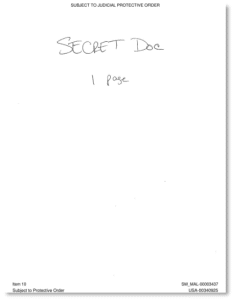

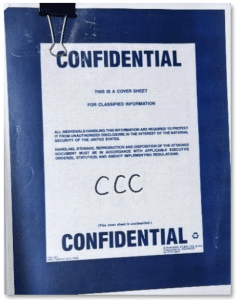

“[Thirteen] boxes or containers contained documents with classification markings, and in all, over one hundred unique documents with classification markings…were seized. Certain of the documents had colored cover sheets indicating their classification status. (Emphasis added.) See, e.g., Attachment F (redacted FBI photograph of certain documents and classified cover sheets recovered from a container in the ‘45 office’).”

The DOJ’s clever wordsmithing, however, did not accurately describe the origin of the cover sheets. In what must be considered not only an act of doctoring evidence but willfully misleading the American people into believing the former president is a criminal and threat to national security, agents involved in the raid attached the cover sheets to at least seven files to stage the photo.

Classified cover sheets were not “recovered” in the container, contrary to Bratt’s declaration to the court. In fact, after being busted recently by defense attorneys for mishandling evidence in the case, Bratt had to fess up about how the cover sheets actually ended up on the documents.

Here is Bratt’s new version of the story, where he finally admits a critical detail that he failed to disclose in his August 2022 filing:

“[If] the investigative team found a document with classification markings, it removed the document, segregated it, and replaced it with a placeholder sheet. The investigative team used classified cover sheets for that purpose.”

But before the official cover sheets were used as placeholder, agents apparently used them as props. FBI agents took it upon themselves to paperclip the sheets to documents—something evident given the uniform nature of how each cover sheet is clipped to each file in the photo—laid them on the floor, and snapped a picture for political posterity. [Italics Julie’s, bold emphasis mine]

Julie’s passage starts by quoting from Bratt’s description of the photo in his August 2022 declaration. The contents of the container in question are clearly identified in the picture as 2A — that is, the contents of box 2. In his declaration, Bratt specifically identifies that the box was recovered in the office. Until DOJ learned of the box of presidential schedules Chamberlain Harris had under her desk in various places, that was the only box known to be seized from the office (though some albums and loose documents were found as well).

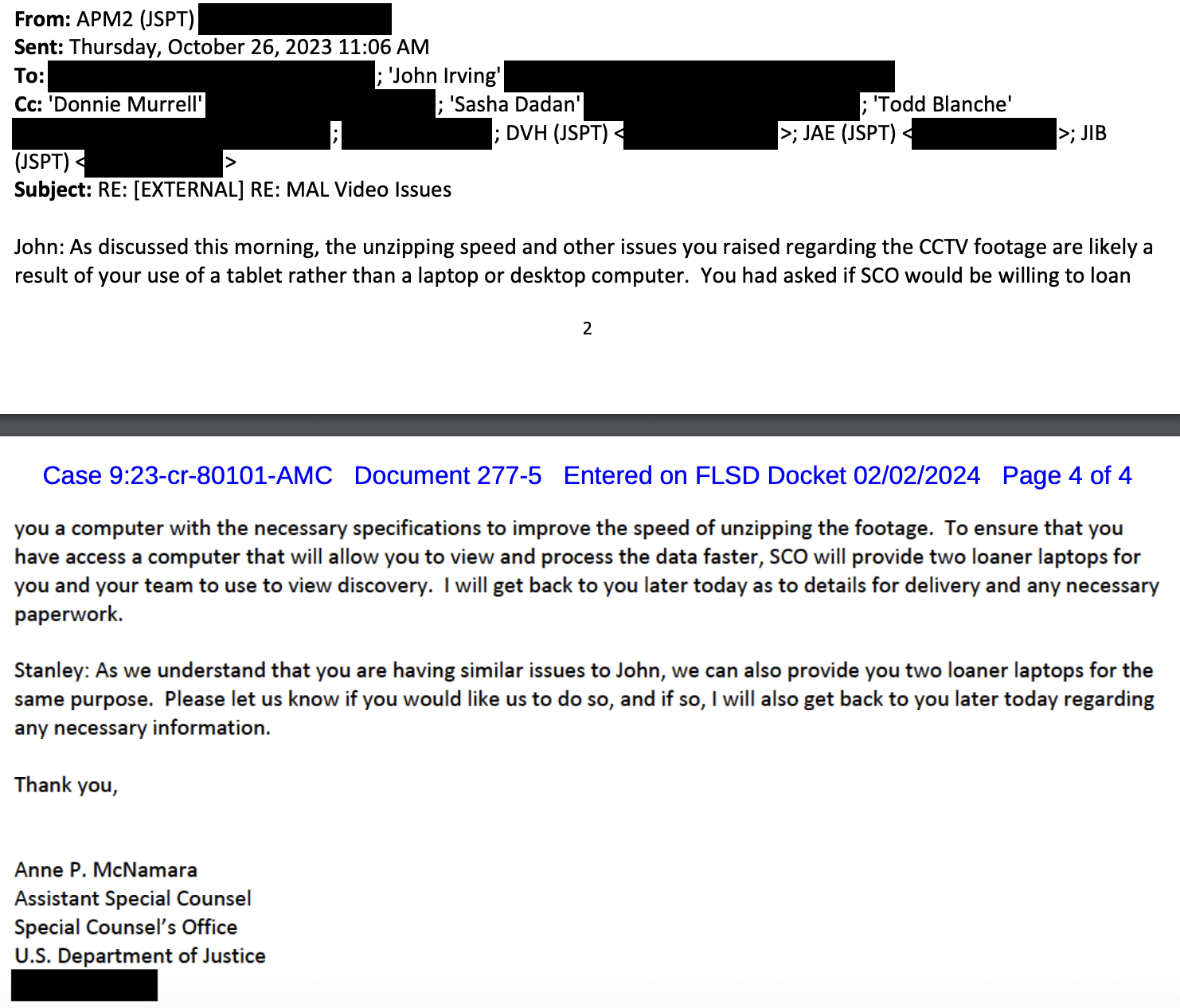

Then, Julie nods to, but does not cite, Stan Woodward’s description of the appearance of slip sheets in boxes of unclassified documents when she describes Bratt as, “being busted recently by defense attorneys.” I quoted Woodward’s filing at length here.

She then quotes from Jay Bratt’s description of something other than that photo: of how, as the FBI searched individual boxes, the FBI inserted a replacement — sometimes a classified cover sheet, but after they ran out of those, a handwritten piece of paper — when it pulled the classified documents from the boxes. Here’s more of what Bratt said.

The filter team took care to ensure that no documents were moved from one box to another, but it was not focused on maintaining the sequence of documents within each box. If a box contained potentially privileged material and fell within the scope of the search warrant, the filter team seized the box for later closer review. If a box did not contain potentially privileged documents, the filter team provided the box to the investigative team for on-site review, and if the investigative team found a document with classification markings, it removed the document, segregated it, and replaced it with a placeholder sheet. The investigative team used classified cover sheets for that purpose, until the FBI ran out because there were so many classified documents, at which point the team began using blank sheets with handwritten notes indicating the classification level of the document(s) seized. The investigative team seized any box that was found to contain documents with classification markings or presidential records.

So Julie relies on (1) a description of a photo of the documents with classification markings removed from box 2 on August 8, 2022, (2) Woodward’s description of what boxes from which documents with classification markings have been removed currently look like, and then (3) Bratt’s description of the search process used in August 2022. From that, she declares that Bratt’s description of some contents of a single box doesn’t match his description of a process used to search boxes and therefore the evidence in the picture must have been doctored.

Already, poor Julie has a problem. First, Bratt’s descriptions are of different things. The August 2022 declaration describes what they found at Mar-a-Lago after pulling documents with classification markings from boxes. The recent response describes what the FBI did when pulling documents with classification markings from boxes.

Woodward, too, describes something different than what Bratt described in August 2022. In the filing that Julie doesn’t cite, Woodward describes what boxes from which documents with classification markings have already been removed currently look like. Again, there is a difference between what remains in boxes versus what got pulled from boxes.

Plus, Bratt’s description is consistent with the picture; Julie’s is not.

Bratt said that a subset of the documents did have cover-sheets — the bit that she italicizes. Julie simply asserts, as fact, that the FBI attached the seven cover sheets that appear in the picture (but for what she imagines is a doctored photo, did not attach cover sheets to the other documents in the picture). To match Bratt’s later description, all the documents with classification markings in the picture would have cover sheets, which also would have made a more damning photo. Julie doesn’t consider the possibility that the seven or so cover sheets in the picture which she describes to be attached to documents were among those documents that Bratt described that did have cover sheets. She doesn’t puzzle through why, if the FBI were trying to make things look as bad as possible, they didn’t put cover sheets on everything.

And to reiterate, this picture does not depict what Julie thinks she’s describing at all; what she’s describing is what got left after the classified documents were segregated from ones without classification markings. What the picture shows on the floor is only documents with classification markings.

It gets worse.

Poor Julie the propagandist states as fact that, “Classified cover sheets were not ‘recovered’ in the container.”

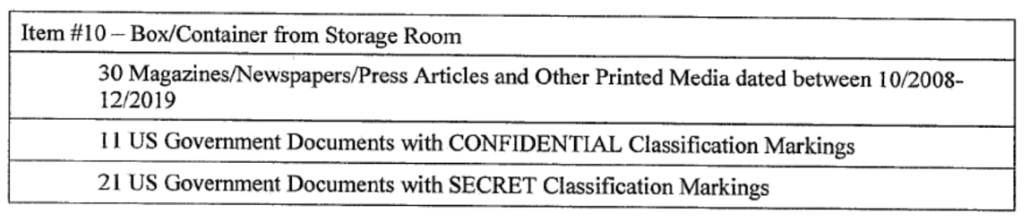

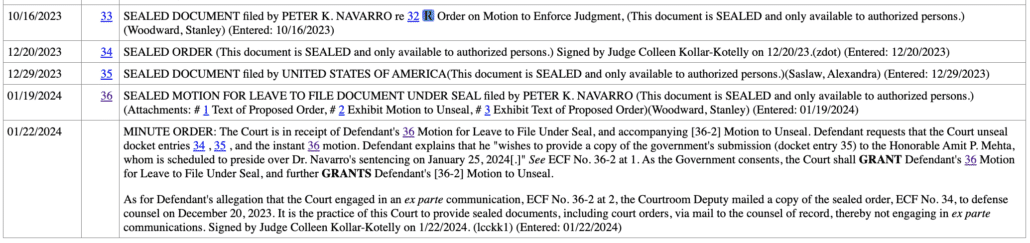

As I noted here, Stan Woodward bases his description of the troubling box with documents out of place as item 10. He describes, “Box A-15 is a box seized from the Storage Room and is identified by the FBI as Item 10.”

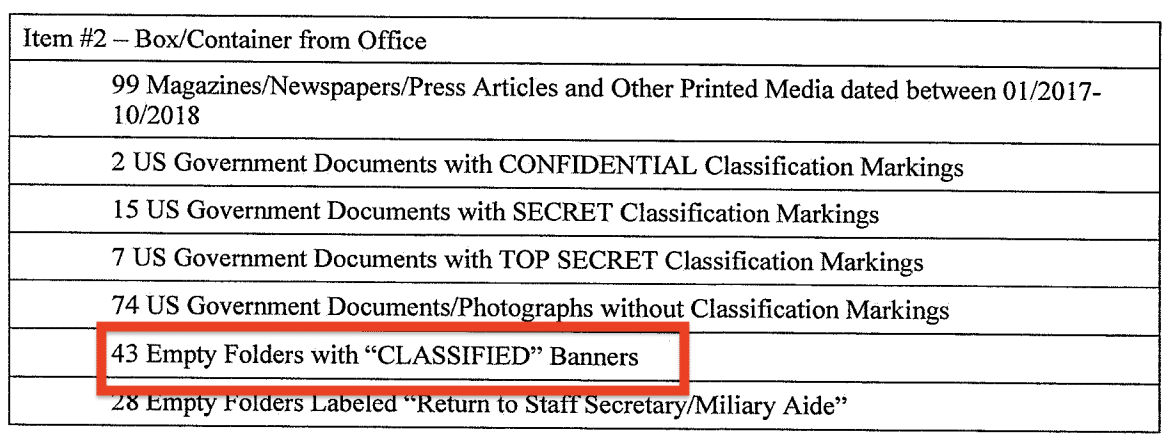

The inventory certified as part of the Special Master process back in September 2022 describes item 10 (identified as box A-15 in the warrant return) this way:

It is, as I noted, the box with the biggest number of classified documents in it, but they were classified at a lower level — Confidential and Secret.

The inventory describes nothing about cover sheets.

But that’s not the box in the picture!! That’s not the box Jay Bratt described back in August 2022!

The box in the picture is box 2, a leatherbound box found in the office.

Here’s how the uncontested description from the Special Master inventory describes that box, the one that Jay Bratt was actually talking about. [my red annotation]

The inventory describes that, in addition to 24 classified documents — 7 of them Top Secret, of which just five are reflected in cover sheets in the picture — there were also 43 empty classified folders.

And yet poor Julie states as fact that, “Classified cover sheets were not “recovered” in the container.” While folders and these cover sheets are different things, they serve to cover classified documents. There were 43 empty classified folders in box 2.

Remember: Tim Parlatore admitted that Trump retained at least one classified cover folder when he was trying to explain why his search team found one marked “Classified Evening Summary” in Trump’s bedroom. Is Julie calling Parlatore a liar now too?

In any case, Julie is talking about an entirely different box, one that the inventory doesn’t record as having any classified cover sheets in it. Based on a claim that item 10 (box A-15) didn’t have cover sheets, Julie stated as fact that item 2 didn’t either.

She simply made it up.

Based on the uncontested inventory, the FBI could have made that picture far more damning than they did, had they paper clipped cover sheets to “each” document with classification marks, as Julie claims they did. They could have put cover sheets on two more Top Secret documents for the picture and added cover sheets on up to 12 more Secret documents. They could have stacked up those 43 empty folders that once had documents in them, but no longer did on August 8, 2022. Instead, they took a picture showing that some of those documents had cover sheets and some did not, which (accurate or not) is precisely what Bratt described, apparently leaving out the 43 damning empty folders altogether.

Poor Julie took a description of a box found in the storage closet, treated it as a description of a box found somewhere else, and then simply never bothered to check what that box — the box Jay Bratt was actually referring to — actually contained.

Julie the propagandist suggests that if the picture were accurate — if there really were seven documents that still had cover sheets in the box that Jay Bratt was actually describing — then it would accurately support an argument that, “the former president is a criminal and threat to national security.” And wow, that may be a problem, conceding that that picture supported an argument that Trump was a national security threat! Because nothing Julie claims in her post describes this box. And her claims that the FBI made this picture as damning as possible is debunked when you look at the actual contents of the box (or even, the picture itself).

So instead, she described something entirely different — something entirely unrelated to the box contents in this picture — and claimed the FBI, and not Julie the propagandist herself, was engaged in deception.

Update: Julie now says that in spite of all the proof she got caught lying, she must still be right because the paperclips in the picture are tidy.