Pandora’s Box Opened: Netanyahu’s Double-Tap Fuck-You

[NB: Note the byline. Portions of this post may be speculative. / ~Rayne]

I wrote a while back about Israel, discussing Israel’s repeated intelligence “failures” as not mere fuck-ups but fuck-yous.

This week’s attacks by exploding electronic devices intended for Hezbollah — attributed to Israel without any denial so far — are yet more fuck-yous delivered using an indiscriminate approach and a double tap.

These fuck-yous blew open Pandora’s box — and then some.

~ ~ ~

On Tuesday nearly 3000 pagers blew up in Lebanon. These one-way pagers are believed to have been distributed to Hezbollah members as a means to bypass Israel’s surveillance of cell phone communications. More than 30 people were killed including children.

On Wednesday during funeral services for persons who died the previous day, walkie-talkies or handheld radios were detonated in Lebanon. 12 more people died and approximately 3000 were injured.

The exploding walkie-talkie attack was the double tap: when persons who escaped a targeted attack gather during a response afterward, a second attack is launched retargeting those same persons. We’ve seen this technique employed by Russia in Ukraine, using secondary attacks to take out first responders aiding the injured and dying in a first attack, or at funeral services for the dead.

It’s a questionable practice; former President Obama had been criticized for its use with drone attacks as double taps may violate the Geneva Conventions and U.S. War Crimes Act of 1996.

But both Tuesday and Wednesday’s attacks may have violated the U.N. Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons regardless of the double tap on Wednesday, as the armed devices constituted booby traps which are prohibited.

These attacks are yet more proof that Israel under Benjamin Netanyahu’s leadership has gone rogue having repeatedly refused to comply with multiple treaties including the Geneva Conventions.

~ ~ ~

This time, though, Israel doesn’t have the excuse that IDF may have made a mistake.

These attacks were premeditated, planned out and executed over months if not years. Front companies were used to obtain components and distribute assembled devices; in the case of the pagers, it’s believed a Hungarian registered firm BAC Consulting may have been a key intermediary between a Taiwanese manufacturer and the ultimate distribution of the devices.

Nonprofit OSINT investigator Bellingcat followed evidence between the pagers and Taiwan electronics firm Gold Apollo, noting that BAC Consulting listed as an employee a “ghost”; this person can’t be traced to any real human, suggesting strongly BAC is an intelligence front.

The operation’s timeline needs to be fleshed out more fully; it’s not clear whether some actions believed to be related to the operation behind this week’s attacks are intended solely for plausible deniability.

02-MAY-2020 — BAC Consulting appears in Hungarian business records but appears now to have been shuttered the same year.

21-MAY-2022 — BAC Consulting registered as a new company in Hungary, according to Hungarian Justice Ministry records. It was listed as a retailer of telecommunications products, management consulting, jewelry making, and fruit cultivator — a rather odd assortment of goods and services.

The business was not engaged in manufacturing according to a spokesperson for Hungary’s prime minister; they also said “the referenced devices have never been in Hungary,” suggesting BAC acted as a broker or trade intermediary.

XXX-2022 to AUG 2024 — Taiwanese electronics manufacturer Gold Apollo exported exported approximately 260,000 pagers over a two-year timeframe. The majority shipped to the EU and US with no records of pagers shipped to Lebanon during that same timeframe. The company received no reports of Gold Apollo pagers exploding.

SUMMER 2022 — Modified pagers containing PETN-adulterated batteries for which BAC was an intermediary began shipping into Lebanon.

APR-MAY 2024 — A Lebanese security source said the pagers had been imported to Lebanon five months ago.

The pagers may have been imported into Lebanon months ago, but they must have been planned out well before that given the prevailing description of the handheld improvised exploding devices (IEDs).

Acceptance of the pagers must have been worked out far earlier — which brand would the users be willing to use, how would they be distributed without raising questions, what could go wrong tipping off the plot between the time the first pagers were fitted up with explosive PETN and detonators, where could the IEDs be assembled without intelligence leaks, so on.

Which brings us to leaks by a pro-Palestinian hacktivist group Handala whose attacks on websites were first noted by computer security expert Kevin Beaumont back in May this year.

After the pager IED explosions on Tuesday, Handala published information about the pagers’ production claiming they had exfiltrated data from Israeli sources Vidisco and Israeli Industrial Batteries Ltd. (IIB).

Vidisco is an Israeli-based developer and manufacturer of X-ray inspection systems; IIB is a manufacturer of batteries which is 51% owned by Sunlight Group as of February 2023. Both appear to be contractors to Israel’s military. Breachsense indicates both firms were hacked and credentials of employees at both firms were leaked though no customer credentials have been.

Handala’s brief about the data it hacked published Wednesday explained the operation:

The operation of the last two days was a series of joint actions of the Mossad and Unit 8200 and a number of shell companies of the Zionist regime! Handala’s hackers, during extensive hacking in recent hours, were able to obtain very secret and confidential information from the operations of the past days, and all the documents will be published in the coming hours!

The summary of the operation is as follows:

* This supply chain attack has taken place by contaminating the batteries of Pagers devices with a special type of heat-sensitive explosive material in the country of origin of the producer!

* Batteries have been contaminated with these explosives by IIB (Israeli Industrial Batteries) company in Nahariya!

* Mossad was responsible for transporting contaminated batteries to the country of origin of the producer!

* Due to the sensitivity of explosives detection devices to these batteries and the need to move them in several countries, Mossad, in cooperation with vidisco shell company, has moved the mentioned shipments!

*Vidisco company is an affiliated company of 8200 unit and today more than 84% of airports and seaports in the world use X-rays produced by this company in their security unit, which actually has a dedicated backdoor of 8200 unit and the Zionist regime it can exclude any shipment it considers in the countries using these devices and prevent the detection of sabotage! ( The complete source code of this project will be published in the next few hours! )

* Contaminated shipments have reached Lebanon through the use of Vidisco backdoor and after traveling through several countries!

* All the factors involved in this operation have been identified by Handala and soon all the data will be published!

* Handala has succeeded in hacking Vidisco and IIB and their 14TB data will be leaked!

More details will be published in the coming hours

(Unit 8200: Israeli Intelligence Corps group)

Beaumont published a short write-up about Handala’s information dump to date, noting the likelihood that Handala is connected to Iran through IP addresses, their talking points, and the targets of their efforts.

Beaumont also asks:

Are the claims credible?

Handala has not yet provided proof of data exfiltration of these organisations. On reaching out, one company above said they are suffering from “IT issues”.

In prior claims by Handala, they have been credible around victim names.

If the battery claims are credible; it is not possible to assess as no evidence has been provided to date.

I’ll note that Handala’s English is very good, though in the age of ChatGPT it may be generated for clarity to English-speaking audiences.

There was no mention of specifics related to handheld radios by Handala in these early releases and if they were likewise products produced by the same after-market suppliers, specialized modifiers, and distribution network.

Reports indicate some of the radios were made by Japanese manufacturer ICOM though ICOM said the model IC-V82 identified was discontinued a decade ago. As damage to recovered radios displayed blast damage in the battery area, it’s possible the radios were retrofitted with explosives or replacement batteries were manufactured with explosives. Because radios and their batteries are larger than pagers, this would explain the larger blasts associated with the radios.

~ ~ ~

Do read the essay by American researcher and hacker Andrew “bunnie” Huang at the link embedded at the phrase “Pandora’s box” above. Huang is deeply concerned about these attacks relying on handheld electronics:

Not all things that could exist should exist, and some ideas are better left unimplemented. Technology alone has no ethics: the difference between a patch and an exploit is the method in which a technology is disclosed. Exploding batteries have probably been conceived of and tested by spy agencies around the world, but never deployed en masse because while it may achieve a tactical win, it is too easy for weaker adversaries to copy the idea and justify its re-deployment in an asymmetric and devastating retaliation.

…

I fear that if we do not universally and swiftly condemn the practice of turning everyday gadgets into bombs, we risk legitimizing a military technology that can literally bring the front line of every conflict into your pocket, purse or home.

I share this concern, one I’ve had for over a decade beginning with reports in 2009-2010 of Chinese-made counterfeit electronics ending up in the U.S. military’s supply chain, compounded by reports in 2018 of unauthorized chips added to server motherboards.

Oversight and investigation into these problems were thwarted by geopolitical, intelligence, and corporate interests.

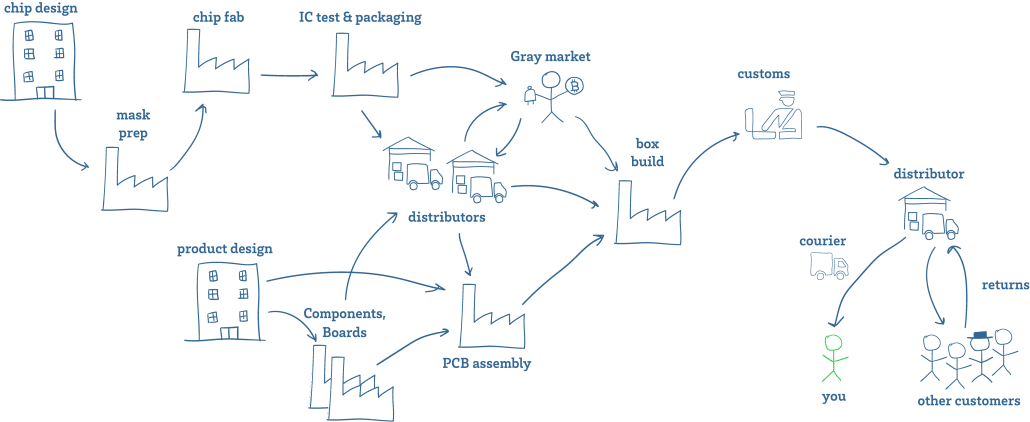

Huang included a nifty visual representation of an electronics supply chain with his essay:

Every point along the supply chain can be breached, whether the items are new or used or refurbished. Huang’s 2019 presentation at BlueHat in Israel on supply chain security looks in detail at the likely points in chip and board production for unauthorized modifications; he doesn’t look far outside manufacturing, though.

What terrifies me is that Israel’s operation revealed far more than supply chains are now threatened. They’ve shown every hostile entity in the world how to wreak massive chaos in ways we haven’t fully imagined.

~ ~ ~

The IEDs have and will continue to attract attention. This week’s double tap attacks made it clear that the proliferation of small electronic devices on which we rely so heavily are the means to destroy both individuals and groups of people.

The information leaked by Handala makes it easy for hostile entities to attempt the same for their own aims.

The attacks have already spurred renewed discussion about onshoring more of our supply chain.

But what concerns me the most is what we’ve learned about the application of X-ray devices in our supply chain and elsewhere.

If Handala could obtain information about this operation — assuming everything revealed so far is truthful and in no way distorted — what other entities may have preceded Handala in breaching Vidisco’s data? How much lead time do they already have toward something similar to this week’s double tap attacks?

If the public and leaked information about Vidisco is accurate, just how badly are U.S. scanning systems compromised? Have we already been allowing Israel (or other opportunists using Israel’s methods and means) to distribute IEDs inside the U.S.? Have our U.S. tax dollars doled out as aid to Israel paid for both the violation of Geneva Conventions, the War Crimes Act, the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons, and now the wholesale compromise of our own national security?

If hostile entities have obtained this same information about Vidisco’s X-ray systems, how badly have our import scanning capabilities been compromised?

If the public and leaked information about Vidisco is accurate and 84% of the world’s airports use its scanning equipment, how badly are our screening systems at U.S. airports compromised?

Imagine for a moment phones and radios on planes containing PETN-adulterated batteries triggered with a single call.

Imagine laptops and tablets triggered with a single remote prompt over onboard WiFi or wireless networks.

~ ~ ~

In June 2017 amid the WannaCry and modified Petya attacks, the Department of Homeland Security and the Travel Safety Administration rolled out heightened security measures including increased scanning of electronic devices.

By the end of July 2017, handling of smaller electronics changed:

… The TSA will now require “all electronics larger than a cell phone” to be removed from carry-on bags and placed in their own separate bin for X-ray screening with nothing on top or below, similar to how laptops have been screened for years. …

At the time the measures appeared to be related to potential threats related to cyber attacks.

Now one might wonder if the changes were intended to increase the use of X-ray screening related specifically to explosives and not just cyber attacks.

We aren’t likely to receive any answers to inquiries about the triggers for these changes.

What we should understand now, though, is that much of this could be performative. The X-ray scanning systems, if tampered with the way they were to admit pagers and radio IEDs into Lebanon, could be absolutely useless for detecting rigged devices.

~ ~ ~

It’s clear we are going to have to rethink our entire screening system at all ports after Netanyahu’s latest fuck-you.

He surely must have known he was opening Pandora’s box when he authorized the detonation of pagers and handheld radios.

I must admit the first thought I had after the initial shock upon hearing about the attacks was this: if Netanyahu had this capability to take out a group of targets this neatly, why didn’t he try this approach with Hamas?

If Netanyahu felt he could expend political capital on violations of international law, why instead is he systematically overseeing the destruction of Gaza’s hospitals, schools, humanitarian aid systems, women and children instead of having neatly excised Hamas in Gaza using these handheld IEDs?

Why? Because fuck you is a likely answer.