ShadowBrokers’ Kiss of Death

In the ShadowBrokers’ latest post, I got a kiss of death. At the end of a long rambling post, TSB called me out — misspelled “EmptyWheel” with initial caps — as “true journalist and journalism is looking like.”

TSB special shouts outs to Marcy “EmptyWheel” Wheeler, is being what true journalist and journalism is looking like thepeoples!

TheShadowBrokers, brokers of shadows.

Forgive me for being an ingrate, but I’m trying to engage seriously on Section 702 reform. Surveillance boosters are already fighting this fight primarily by waging ad hominem attacks. Having TSB call me out really makes it easy for surveillance boosters to suggest I’m not operating in the good faith I’ve spent 10 years doing.

Way to help The Deep State, TSB.

Worse still, TSB lays out a load of shit. A central focus of the post (and perhaps the reason for my Kiss of Death) is the latest fear-mongering about Russian AV firm, Kaspersky.

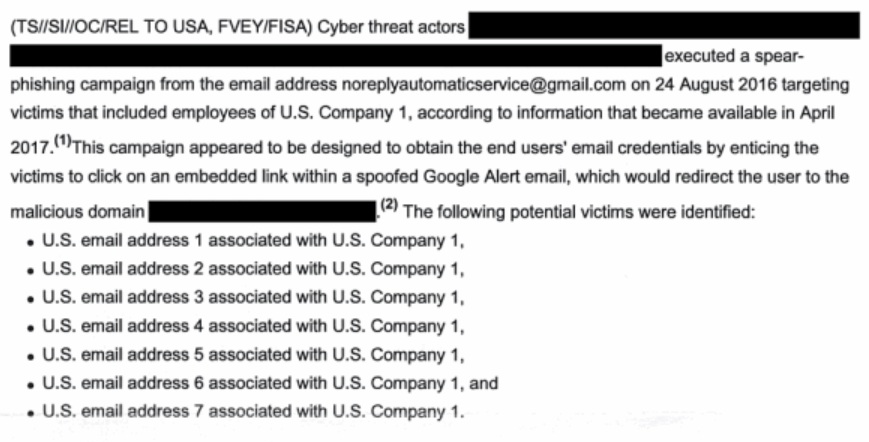

Are ThePeoples enjoying seven minutes of hate at Russian hackers and Russian security company? Is after October 1st, new moneys is being in US government budgets for making information warfares payments. Is many stories of NSA + lost data. Is all beings true? Is NSA chasing shadowses? Is theequationgroup still not knowing hows thems getting fucked? Is US government trying out storieses to be seeing responses? TheShadowBrokers be telling ThePeoples year ago how theshadowbrokers is getting data. ThePeoples is no believing. ThePeoples is got jokes. ThePeoples is making shits up. So TheShadowBrokers then saying fucks it, theshadowbrokers can be doings that too.

TheShadowBrokers is thinkings The Peoples is missings most important part of storieses. Corporate media company (WSJ) publishes story with negative financial impacts to foreign company (Kaspersky Labs) FROM ANONYMOUS SOURCE WITH NO PHYSICAL EVIDENCE. WTF? Can they being doing that? Libel law suits? But is ok, Kaspersky is Russian security peoples. Russian security peoples is being really really, almost likes, nearly sames as Russian hackers. Is like werewolves. Russian security peoples is becoming Russian hackeres at nights, but only full moons. AND AMERICA HATES RUSSIAN HACKERS THEY HACKED OUR ELECTION CIA, GOOGLE, AND FACEBOOK SAID. If happening to one foreign company can be happening to any foreign company? If happening to foreign company can be happen to domestic? Microsoft Windows 10 “free” = “free” telemetry in Microsoft cloud.

TSB tries to claim that the Kaspersky stories are a US government attempt to explain how TSB got the files he is dumping. But as I have pointed out — even the NYT story on this did — it doesn’t make sense. That’s true, in part because if the government had identified the files the TAO hacker exposed to Kaspersky in spring 2016 as Shadowbrokers’, they wouldn’t have gone on to suggest the files came from Hal Martin when they arrested him. Mind you, Martin’s case has had a series of continuations, which suggests he may be cooperating, so maybe he confessed to be running Kaspersky on his home machine too? But even there, they’d have known that long before now.

Plus, TSB was the first person to suggest he got his files from Kaspersky. TSB invoked Kaspersky in his first post.

We find cyber weapons made by creators of stuxnet, duqu, flame. Kaspersky calls Equation Group. We follow Equation Group traffic.

And TSB more directly called out Kaspersky in the 8th message, on January 8, just as the US government was unrolling its reports on the DNC hack.

Before go, TheShadowBrokers dropped Equation Group Windows Warez onto system with Kaspersky security product. 58 files popped Kaspersky alert for equationdrug.generic and equationdrug.k TheShadowBrokers is giving you popped files and including corresponding LP files.

The latter is a point fsyourmoms made in a post and an Anon made on Twitter; I had made it in an unfinished post I accidentally briefly posted on September 15.

But I don’t think the Kaspersky call-out in January is as simple as people make it out to be.

First, as Dan Goodin and Jake Williams noted collectively at the time, the numbers were off, particularly with regards to whether all of them were detected by Kaspersky products.

The post included 61 Windows-formatted binary files, including executables, dynamic link libraries, and device drivers. While, according to this analysis, 43 of them were detected by antivirus products from Kaspersky Lab, which in 2015 published a detailed technical expose into the NSA-tied Equation Group, only one of them had previously been uploaded to the Virus Total malware scanning service. And even then, Virus Total showed that the sample was detected by only 32 of 58 AV products even though it had been uploaded to the service in 2009. After being loaded into Virus Total on Thursday, a second file included in the farewell post was detected by only 12 of the 58 products.

Most weren’t uploaded to Virus Total, but that’s interesting for another reason. The dig against Kaspersky back in 2015 — based off leaked emails that might have come from hacking it — is that in 2009 they were posting legit files onto Virus Total to catch other companies lifting its work.

At that level, then, the reference to Kaspersky could be another reference to insider knowledge, as TSB made elsewhere.

But there are several other details of note regarding that January post.

First, it was a huge headfake. It came four days after TSB had promised to post the guts of the Equation Group warez — Danderspritz and the other powerful tools that would eventually get released in April in the Lost in Translation post, which would in turn lead to WannaCry. Having promised some of NSA’s best and reasonably current tools (which may have led NSA to give Microsoft the heads up to patch), TSB instead posted some older ones that mostly embarrassed Kaspersky.

And that was supposed to be the end of things. TSB promised to go away forever.

So long, farewell peoples. TheShadowBrokers is going dark, making exit. Continuing is being much risk and bullshit, not many bitcoins.

As such, the events of that week were almost like laying an implicit threat as the US intelligence community’s Russian reports came out and the Trump administration began, but backing off that threat.

But I’m not sure why anyone would have an incentive to out Kaspersky like this. Why would TSB want to reveal the real details how he obtained these files?

Two other things may be going on.

First, the original TSB post was accompanied by the characters shi pei.

I haven’t figured out what that was supposed to mean. It might mean something like “screw up,” or it might be reference using the wrong characters to Madame Butterfly (is this even called a homophone in Mandarin, where intonations mean all?), Shi Pei Pu, the drag Chinese opera singer who spied on France for 20 years. [Update: Google Translate says it is “loser”.] I welcome better explanations for what the characters might mean in this context. But if it means either of those things, they might be a reference to the December arrest, on treason charges, of Kaspersky researcher Ruslan Stoyanov, who along with cooperating with US authorities against some Russian spammers, may have also received payment from foreign companies. That is, either one might have been a warning to Kaspersky as much as an expose of TSB’s sources.

[Update on shi pei, from LG’s comment: “It’s a polite formula meaning: “excuse me (I must be going)” or simply “goodbye”, which would make sense given that the post indicated that they intended to retire.”]

All of which is to say, I have no idea what this January post was really intended to accomplish (I have some theories I won’t make public), but it seems far more complex than an early admission that Russia was stealing NSA files by exploiting Kaspersky AV. And if it was meant to expose TSB’s own source, it was likely misdirection.

For what it’s worth, with respect to my Kiss of Death, my post on the possibility TSB shares “the second source” with Jake Appelbaum got at least as much interesting attention as my briefly posted post on the earlier TSB Kaspersky post.

In any case, I think the far more interesting call out than mine in TSB’s post is that he gives Matt Suiche. Ostensibly, TSB apologizes for missing his Black Hat talk.

TheShadowBrokers is sorry TheShadowBrokers is missing you at theblackhats or maybe not? TSB is not seeing hot reporter lady giving @msuiche talk, was that not being clear required condition? TheShadowBrokers is being sures you understanding, law enforcements, not being friendly fans of TSB. Maybe someday. Dude? “…@shadowbrokerss does not do thanksgiving. TSB is the real Infosec Santa Claus…” really? “Trick or Treet”, cosplay and scarring shits out of thepeoples? TheShadowBrokers favorite holiday, not holiday, but should be being, Halloween!

Of course, TSB could have done that in last month’s post. Instead, this reference is a response to this thread on whether he might dump something on Thanksgiving to be particularly disruptive. In which case, it seems to be a tacit threat: that he will dump on Halloween, just a few weeks away.

![[Photo: National Security Agency, Ft. Meade, MD via Wikimedia]](https://www.emptywheel.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/NationalSecurityAgency_HQ-FortMeadeMD_Wikimedia.jpg)