The other day, I laid out the continuing fight between Director of National Intelligence Dan Coats and Senator Ron Wyden over the former’s unwillingness to explain why he can’t answer the question, “Can the government use FISA Act Section 702 to collect communications it knows are entirely domestic?” in unclassified form. As I noted, Coats is parsing the difference between “intentionally acquir[ing] any communication as to which the sender and all intended recipients are known at the time of acquisition to be located in the United States,” which Section 702 prohibits, and “collect[ing] communications [the government] knows are entirely domestic,” which this exchange and Wyden’s long history of calling out such things clearly indicates the government does.

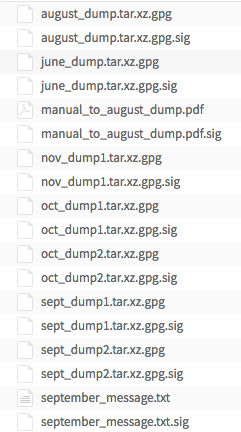

As I noted, the earlier iteration of this debate took place in early June. Since then, we’ve gotten two sets of documents that all but prove that the entirely domestic communication the NSA refuses to tell us about involves communications that obscure their location, probably via Tor or VPNs.

Most Entirely Domestic Communications Collected Via Upstream Surveillance in 2011 Obscured Their Location

The first set of documents are those on the 2011 discussion about upstream collection liberated just recently by Charlie Savage. They show that in the September 7, 2011 hearing, John Bates told the government that he believed the collection of discrete communications the government had not examined in their sampling might also contain “about” communications that were entirely domestic. (PDF 113)

We also have this other category, in your random sampling, again, that is 9/10ths of the random sampling that was set aside as being discrete communications — 45,000 out of the 50,0000 — as to which our questioning has indicataed we have a concern that some of the about communications may actually have wholly domestic communications.

And I don’t think that you’ve really assessed that, either theoretically or by any actual examination of those particular transactions or communications. And I’m not indicating to you what I expect you to do, but I do have this concern that there are a fair number of wholly domestic communications in that category, and there’s nothing–you really haven’t had an opportunity to address that, but there’s nothing that has been said to date that would dissuade me from that conclusion. So I’m looking there for some convincing, if you will, assessment of why there are not wholly domestic communications with that body which is 9/10s of the random sample.

In a filing submitted two days later, the government tried to explain away the possibility this would include (many) domestic communications. (The discussion responding to this question starts at PDF 120.) First, the NSA used technical means to determine that 41,272 of the 45,359 communications in the sample were not entirely domestic. That left 4,087 communications, which the NSA was able to analyze in just 48 hours. Of those, the NSA found just 25 that were not to or from a tasked selector (meaning they were “abouts” or correlated identities, described as “potentially alternate accounts/addresses/identifiers for current NSA targets” in footnote 7, which may be the first public confirmation that NSA collects on correlated identifiers). NSA then did the same kind of analysis it does on the communications that it does as part of its pre-tasking determination that a target is located outside the US. This focused entirely on location data.

Notably, none of the reviewed transactions featured an account/address/identifier that resolved to the United States. Further, each of the 25 communications contained location information for at least one account/address/identifier such that NSA’s analysts were able assess [sic] that at least one communicant for each of these 25 communications was located outside of the United States. (PDF 121)

Note that the government here (finally) drops the charade that these are simply emails, discussing three kinds of collection: accounts (which could be both email and messenger accounts), addresses (which having excluded accounts would significantly include IP addresses), and identifiers. And they say that having identified an overseas location for the communication, NSA treats it as an overseas communication.

The next paragraph is even more remarkable. Rather than doing more analysis on those just 25 communications it effectively argues that because latency is bad, it’s safe to assume that any service that is available entirely within the US will be delivered to an American entirely within the US, and so those 25 communications must not be American.

Given the United States’ status as the “world’s premier electronic communications hub,” and further based on NSA’s knowledge of Internet routing patterns, the Government has already asserted that “the vast majority of communications between persons located in the United States are not routed through servers outside the United Staes.” See the Government’s June 1, 2011 Submission at 11. As a practical matter, it is a common business practice for Internet and web service providers alike to attempt to deliver their customers the best user experience possible by reducing latency and increasing capacity. Latency is determined in part by the geographical distance between the user and the server, thus, providers frequently host their services on servers close to their users, and users are frequently directed to the servers closest to them. While such practices are not absolute in any respect and are wholly contingent on potentially dynamic practices of particular service providers and users,9 if all parties to a communication are located in the United States and the required services are available in the United States, in most instances those communications will be routed by service providers through infrastructure wholly within the United States.

Amid a bunch of redactions (including footnote 9, which is around 16 lines long and entirely redacted), the government then claims that its IP filters would ensure that it wouldn’t pick up any of the entirely domestic exceptions to what I’ll call its “avoidance of latency” assumption and so these 25 communications are no biggie, from a Fourth Amendment perspective.

Of course, the entirety of this unredacted discussion presumes that all consumers will be working with providers whose goal is to avoid latency. None of the unredacted discussion admits that some consumers choose to accept some latency in order to obscure their location by routing it through one (VPN) or multiple (Tor) servers distant from their location, including servers located overseas.

For what it’s worth, I think the estimate Bates did on his own to come up with a number of these SCTs was high, in 2011. He guessed there would be 46,000 entirely domestic communications collected each year; by my admittedly rusty math, it appears it would be closer to 12,000 (25 / 50,000 comms in the sample = .05% of the total; .05% of the 11,925,000 upstream transactions in that 6 month period = 5,962, times 2 = roughly 12,000 a year). Still, it was a bigger part of the entirely domestic upstream collection than those collected as MCTs, and all those entirely domestic communications have been improperly back door searched in the interim.

Collyer claims to have ended “about” collection but admits upstream will still collect entirely domestic communications

Now, if that analysis done in 2011 were applicable to today’s collection, there shouldn’t be a way for the NSA to collect entirely domestic communications today. That’s because all of those 25 potentially domestic comms were described as “about” collection. Rosemary Collyer has, according to her IMO apparently imperfect understanding of upstream collection, shut down “about” collection. So that should have eliminated the possibility for entirely domestic collection via upstream, right?

Nope.

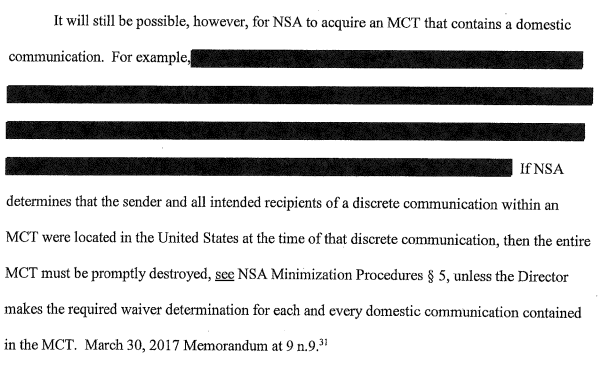

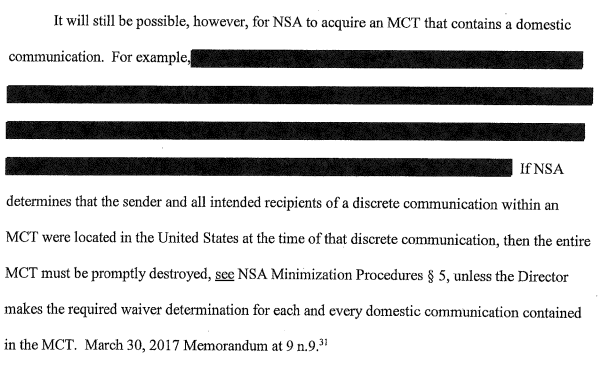

As she admits in her opinion, it will still be possible for the NSA to “acquire an MCT” (that is, bundled collection) “that contains a domestic communication.”

So there must be something that has changed since 2011 that would lead NSA to collect entirely domestic communications even if that communication didn’t include an “about” selector.

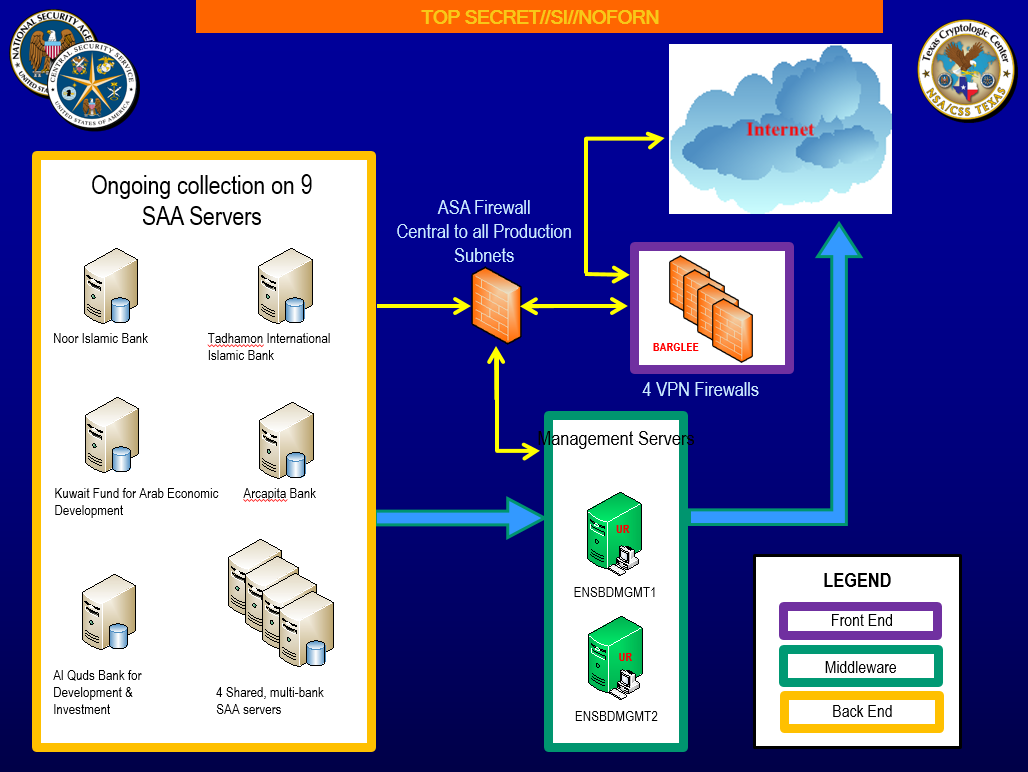

In 2014 Collyer enforced a practice that would expose Americans to 702 collection

Which brings me back to the practice approved in 2014 in which, according to providers newly targeted under the practice, “the communications of U.S. person will be collected as part of such surveillance.”

As I laid out in this post, in 2014 Thomas Hogan approved a change in the targeting procedures. Previously, all users of a targeted facility had to be foreign for it to qualify as a foreign target. But for some “limited” exception, Hogan for the first time permitted the NSA to collect on a facility even if Americans used that facility as well, along with the foreign targets.

The first revision to the NSA Targeting Procedures concerns who will be regarded as a “target” of acquisition or a “user” of a tasked facility for purposes of those procedures. As a general rule, and without exception under the NSA targeting procedures now in effect, any user of a tasked facility is regarded as a person targeted for acquisition. This approach has sometimes resulted in NSA’ s becoming obligated to detask a selector when it learns that [redacted]

The relevant revision would permit continued acquisition for such a facility.

It appears that Hogan agreed it would be adequate to weed out American communications after collection in post-task analysis.

Some months after this change, some providers got some directives (apparently spanning all three known certificates), and challenged them, though of course Collyer didn’t permit them to read the Hogan opinion approving the change.

Here’s some of what Collyer’s opinion enforcing the directives revealed about the practice.

Collyer’s opinion includes more of the provider’s arguments than the Reply did. It describes the Directives as involving “surveillance conducted on the servers of a U.S.-based provider” in which “the communications of U.S. person will be collected as part of such surveillance.” (29) It says [in Collyer’s words] that the provider “believes that the government will unreasonably intrude on the privacy interests of United States persons and persons in the United States [redacted] because the government will regularly acquire, store, and use their private communications and related information without a foreign intelligence or law enforcement justification.” (32-3) It notes that the provider argued there would be “a heightened risk of error” in tasking its customers. (12) The provider argued something about the targeting and minimization procedures “render[ed] the directives invalid as applied to its service.” (16) The provider also raised concerns that because the NSA “minimization procedures [] do not require the government to immediately delete such information[, they] do not adequately protect United States person.” (26)

[snip]

Collyer, too, says a few interesting things about the proposed surveillance. For example, she refers to a selector as an “electronic communications account” as distinct from an email — a rare public admission from the FISC that 702 targets things beyond just emails. And she treats these Directives as an “expansion of 702 acquisitions” to some new provider or technology.

Now, there’s no reason to believe this provider was involved in upstream collection. Clearly, they’re being asked to provide data from their own servers, not from the telecom backbone (in fact, I wonder whether this new practice is why NSA has renamed “PRISM” “downstream” collection).

But we know two things. First: the discrete domestic communications that got sucked up in upstream collection in 2011 appear to have obscured their location. And, there is now a means of collecting bundles of communications via upstream collection (assuming Collyer’s use of MCT here is correct, which it might not be) such that even communications involving no “about” collection would be swept up.

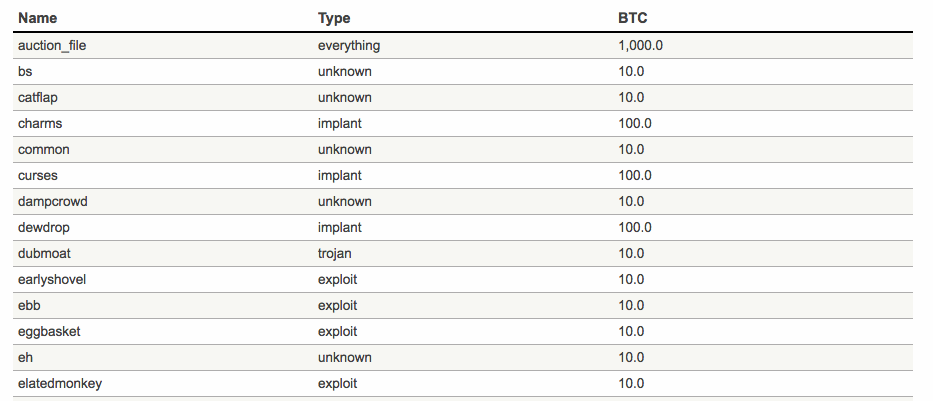

Again, the evidence is still circumstantial, but there is increasing evidence that in 2014 the NSA got approval to collect on servers that obscure location, and that that is the remaining kind of collection (which might exist under both upstream and downstream collection) that will knowingly be swept up under Section 702. That’s the collection, it seems likely, that Coats doesn’t want to admit.

The problems with permitting collection on location-obscured Americans

If I’m right about this, then there are three really big problems with this practice.

First, in 2011, location-obscuring servers would not themselves be targeted. Communications using such servers would only be collected (if the NSA’s response to Bates is to be believed) if they included an “about’ selector.

But it appears there is now some collection that specifically targets those location-obscuring servers, and knowingly collects US person communications along with whatever else the government is after. If that’s right, then it will affect far more than just 12,000 people a year.

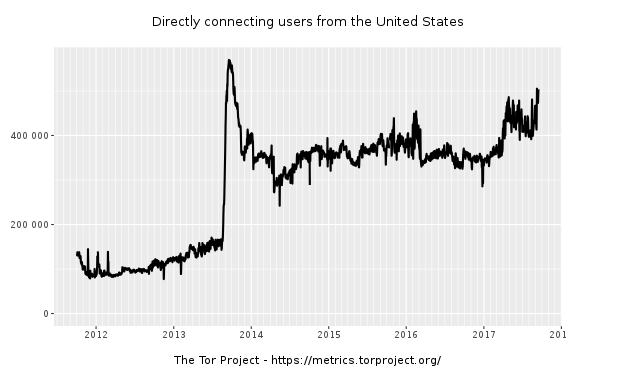

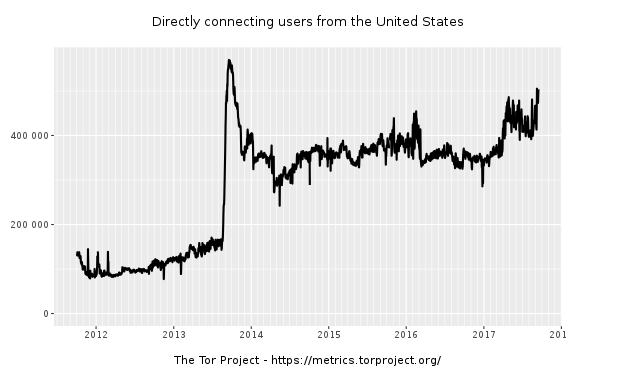

That’s especially true given that a lot more people are using location-obscuring servers now than on October 3, 2011, when Bates issued his opinion. Tor usage in the US has gone from around 150,000 mean users a day to around 430,000 users.

And that’s just Tor. While fewer VPN users will consistently use overseas servers, sometimes it will happen for efficacy reasons and sometimes it will happen to access content that is unavailable in the US (like decent Olympics coverage).

In neither of Collyer’s opinions did she ask for the kind of numerical counts of people affected that Bates asked for in 2011. If 430,000 Americans a day are being exposed to this collection under the 2014 change, it represents a far bigger problem than the one Bates called a Fourth Amendment violation in 2011.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, Collyer newly permitted back door searches on upstream collection, even though she knew that (for some reason) it would still collect US person communications. So not only could the NSA collect and hold location obscured US person communications, but those communications might be accessed (if they’re not encrypted) via back door searches that (with Attorney General approval) don’t require a FISA order (though Americans back door searched by NSA are often covered by FISA orders).

In other words, if I’m right about this, the NSA can use 702 to collect on Americans. And the NSA will be permitted to keep what they find (on a communication by communication basis) if they fall under four exceptions to the destruction requirement.

The government is, once again, fighting Congressional efforts to provide a count of how many Americans are getting sucked up in 702 (even though the documents liberated by Savage reveal that such a count wouldn’t take as long as the government keeps claiming). If any of this speculation is correct, it would explain the reluctance. Because once the NSA admits how much US person data it is collecting, it becomes illegal under John Bates’ 2010 PRTT order.

![[Photo: National Security Agency, Ft. Meade, MD via Wikimedia]](https://www.emptywheel.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/NationalSecurityAgency_HQ-FortMeadeMD_Wikimedia.jpg)