Did NSA Interpret Adverse FISC Fourth Amendment Ruling as Permission to Search American Contacts?

Finally! The backdoor!

The Guardian today confirms what Ron Wyden and, before him, Russ Feingold have warned about for years. In a glossary updated in June 2012, the NSA claims that minimization rules “approved” on October 3, 2011 “now allow for use of certain United States person names and identifiers as query terms.”

A secret glossary document provided to operatives in the NSA’s Special Source Operations division – which runs the Prism program and large-scale cable intercepts through corporate partnerships with technology companies – details an update to the “minimization” procedures that govern how the agency must handle the communications of US persons. That group is defined as both American citizens and foreigners located in the US.

“While the FAA 702 minimization procedures approved on 3 October 2011 now allow for use of certain United States person names and identifiers as query terms when reviewing collected FAA 702 data,” the glossary states, “analysts may NOT/NOT [not repeat not] implement any USP [US persons] queries until an effective oversight process has been developed by NSA and agreed to by DOJ/ODNI [Office of the Director of National Intelligence].”

The term “identifiers” is NSA jargon for information relating to an individual, such as telephone number, email address, IP address and username as well as their name.

The document – which is undated, though metadata suggests this version was last updated in June 2012 – does not say whether the oversight process it mentions has been established or whether any searches against US person names have taken place.

The Guardian goes on to quote Ron Wyden confirming that this is the back door he’s been warning about for years.

Once Americans’ communications are collected, a gap in the law that I call the ‘back-door searches loophole’ allows the government to potentially go through these communications and conduct warrantless searches for the phone calls or emails of law-abiding Americans.

But the Guardian is missing one critical part of this story.

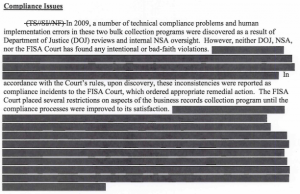

The FISC Court didn’t just “approve” minimization procedures on October 3, 2011. In fact, that was the day that it declared that part of the program — precisely pertaining to minimization procedures — violated the Fourth Amendment.

So where the glossary says minimization procedures approved on that date “now allow” for querying US person data, it almost certainly means that on October 3, 2011, the FISC court ruled the querying the government had already been doing violated the Fourth Amendment, and sent it away to generate “an effective oversight process,” even while approving the idea in general.

And note that FISC didn’t, apparently, require that ODNI/DOJ come back to the FISC to approve that new “effective oversight process.”

Consider one more thing.

As I have repeatedly highlighted, the Senate Intelligence Committee (and the Senate Judiciary Committee, though there’s no equivalent report) considered whether to regulate precisely this issue last year when extending the FISA Amendments Act.

Finally, on a related matter, the Committee considered whether querying information collected under Section 702 to find communications of a particular United States person should be prohibited or more robustly constrained. As already noted, the Intelligence Community is strictly prohibited from using Section 702 to target a U.S. person, which must at all times be carried out pursuant to an individualized court order based upon probable cause. With respect to analyzing the information lawfully collected under Section 702, however, the Intelligence Community provided several examples in which it might have a legitimate foreign intelligence need to conduct queries in order to analyze data already in its possession. The Department of Justice and Intelligence Community reaffirmed that any queries made of Section 702 data will be conducted in strict compliance with applicable guidelines and procedures and do not provide a means to circumvent the general requirement to obtain a court order before targeting a U.S. person under FISA.

But in spite of Ron Wyden and Mark Udall’s best efforts — and, it now appears, in spite of FISC concerns about precisely this issue — the Senate Intelligence Committee chose not to do so.

This strongly suggests that the concerns FISC had about the Fourth Amendment directly pertained to this backdoor search. But if that’s the case, it also suggests that none of NSA’s overseers — not the Intelligence Committees, not ODNI/DOJ, and not FISC — have bothered to actually close that back door.