David Weiss Is a Direct Witness to the Crimes on Which He Indicted Alexander Smirnov

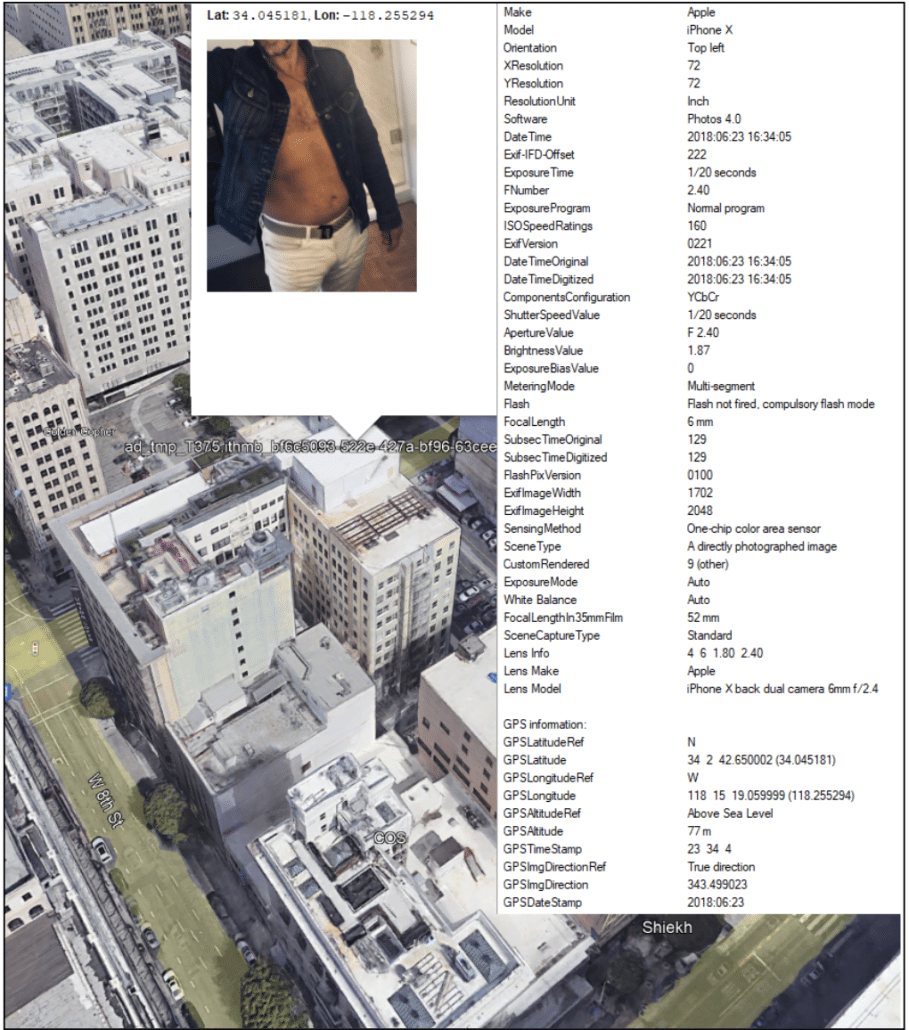

On the day that Bill Barr aggressively intervened in the parallel impeachment inquiry and Hunter Biden prosecutions last summer, David Weiss’ office sent out a final deal that would resolve Hunter’s case with no jail time and no further investigation. Within weeks, amid an uproar about claims in an FD-1023 that David Weiss now says were false, Weiss reneged on that deal. With the indictment yesterday of Alexander Smirnov, the source of those false claims, Weiss confesses he is a direct witness in an attempt to frame Joe Biden, even as he attempts to bury it.

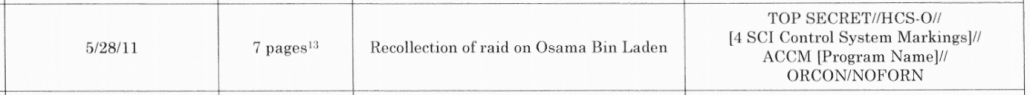

On June 7, 2023, Bill Barr went on the record to refute several things that Jamie Raskin described learning about Smirnov’s FD-1023. Specifically, the former Attorney General insisted that the investigation into the allegations Smirnov made continued under David Weiss.

It’s not true. It wasn’t closed down,” William Barr told The Federalist on Tuesday in response to Democrat Rep. Jamie Raskin’s claim that the former attorney general and his “handpicked prosecutor” had ended an investigation into a confidential human source’s allegation that Joe Biden had agreed to a $5 million bribe. “On the contrary,” Barr stressed, “it was sent to Delaware for further investigation.”

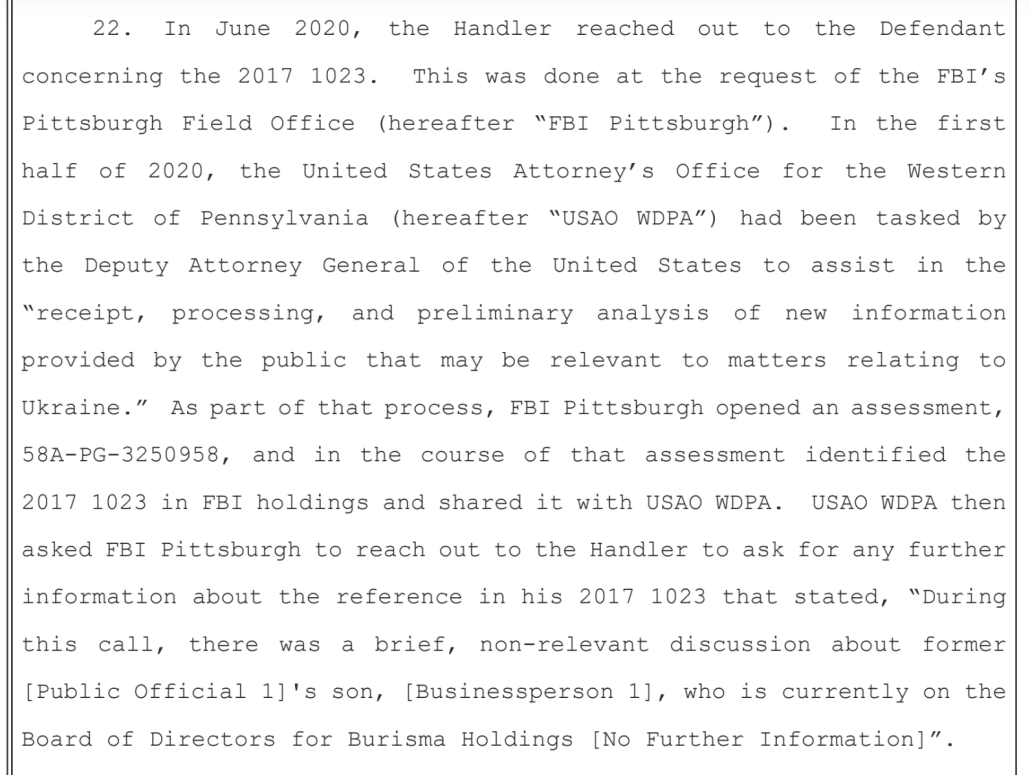

“It wasn’t closed down,” Bill Barr claimed. As I’ll show below, according to the indictment obtained under David Weiss’ authority yesterday, that’s a lie. “It was sent to [David Weiss] for further investigation,” Bill Barr claimed, not confessing that it was sent to Delaware on October 23, 2020, days after Trump had yelled at him personally about the investigation into Hunter Biden. According to Barr, Weiss was tasked with doing more investigation into the Smirnov claims than Scott Brady had already done.

In the Smirnov indictment, Weiss now says that he only did that investigation last year, and almost immediately discovered the allegations were false.

The same day the Federalist published those Barr claims, June 7, and one day after Hunter Biden attorney Chris Clark spoke personally with David Weiss, Lesley Wolf sent revised language for the diversion agreement that strengthened Hunter Biden’s protection against any further prosecution.

The United States agrees not to criminally prosecute Biden, outside of the terms of this Agreement, for any federal crimes encompassed by the attached Statement of Facts (Attachment A) and the Statement of Facts attached as Exhibit 1 to the Memorandum of Plea Agreement filed this same day.

That language remains in the diversion agreement Leo Wise signed on July 26, 2023.

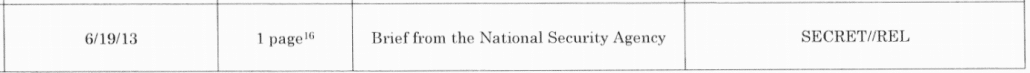

According to an unrebutted claim from Clark, on June 19, 2023, Weiss’ First AUSA Shannon Hanson assured him there was no ongoing investigation into his client.

36. Shortly after that email, I had another phone call with AUSA Hanson, during which AUSA Hanson requested that the language of Mr. Biden’s press statement be slightly revised. She proposed saying that the investigation would be “resolved” rather than “concluded.” I then asked her directly whether there was any other open or pending investigation of Mr. Biden overseen by the Delaware U.S. Attorney’s Office, and she responded there was not another open or pending investigation.

That day, June 19, was the first day Wise made an appearance on the case.

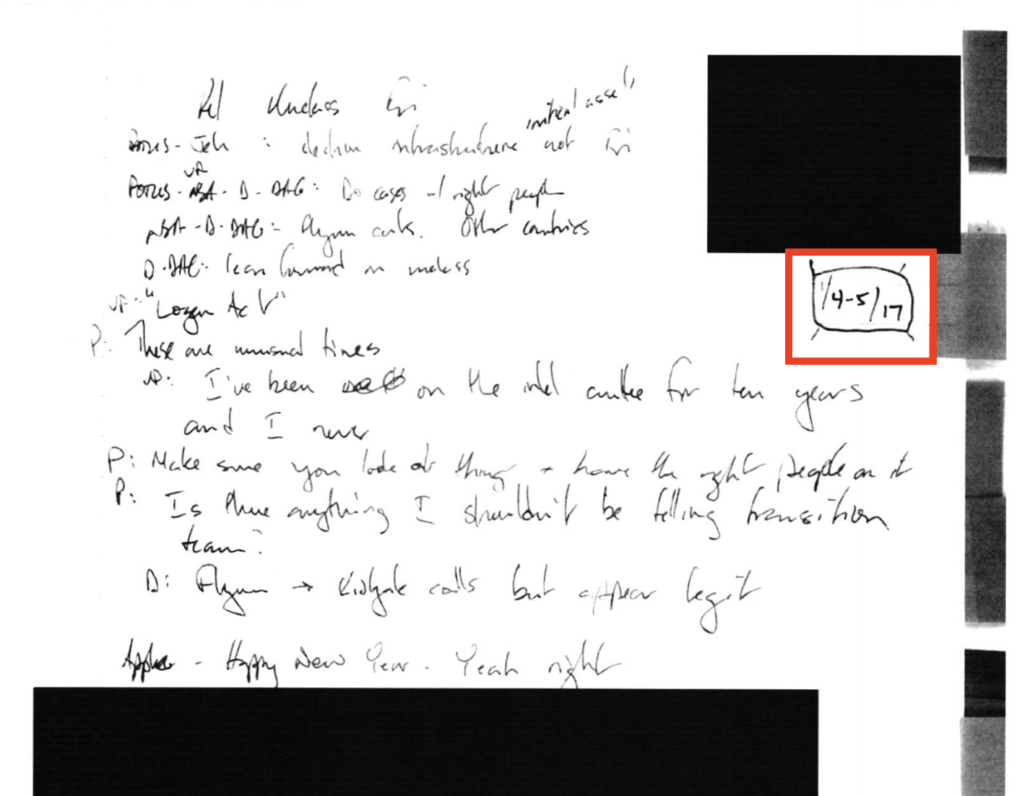

On July 10, a month after the former Attorney General had publicly claimed that his office sent the Smirnov FD-1023 to Weiss’ office for further investigation in 2020, Weiss responded to pressure from Lindsey Graham explaining why he couldn’t talk about the FD-1023: “Your questions about allegations contained in an FBI FD-1023 Form relate to an ongoing investigation.” The next day, Hanson fielded a request from Clark, noting she was doing so because “the team” was in a secure location unable to do so themselves. “The team” should have had no purpose being in a secure location; they should have been preparing for the unclassified plea deal.

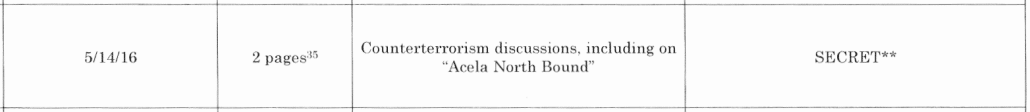

By July 26, the same day Leo Wise signed a diversion agreement that said Hunter wouldn’t be further charged, he made representations that conflicted with the document he had signed, claiming Hunter could still be charged with FARA. That was how, with David Weiss watching, Wise reneged on a signed plea deal and reopened the investigation into Hunter Biden, leading to two indictments charging six felonies and six misdemeanors.

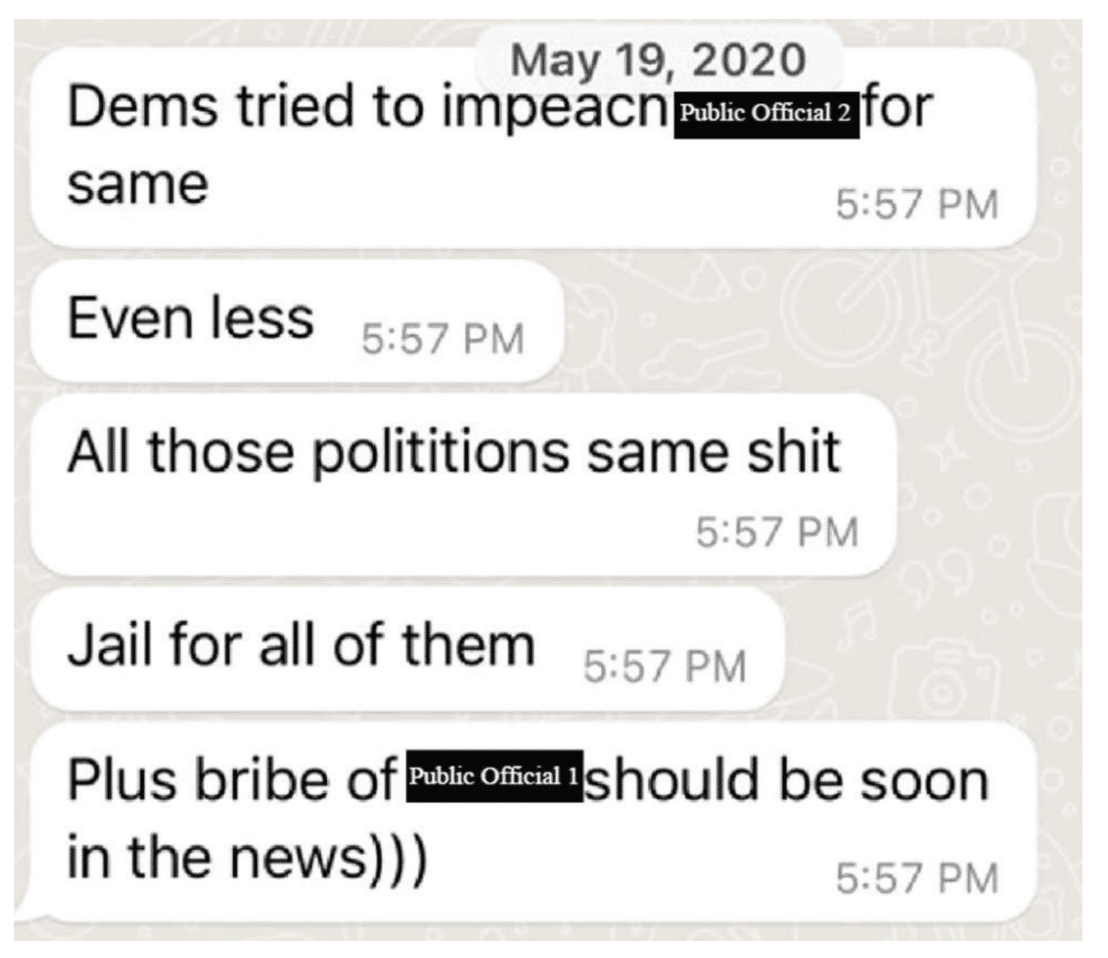

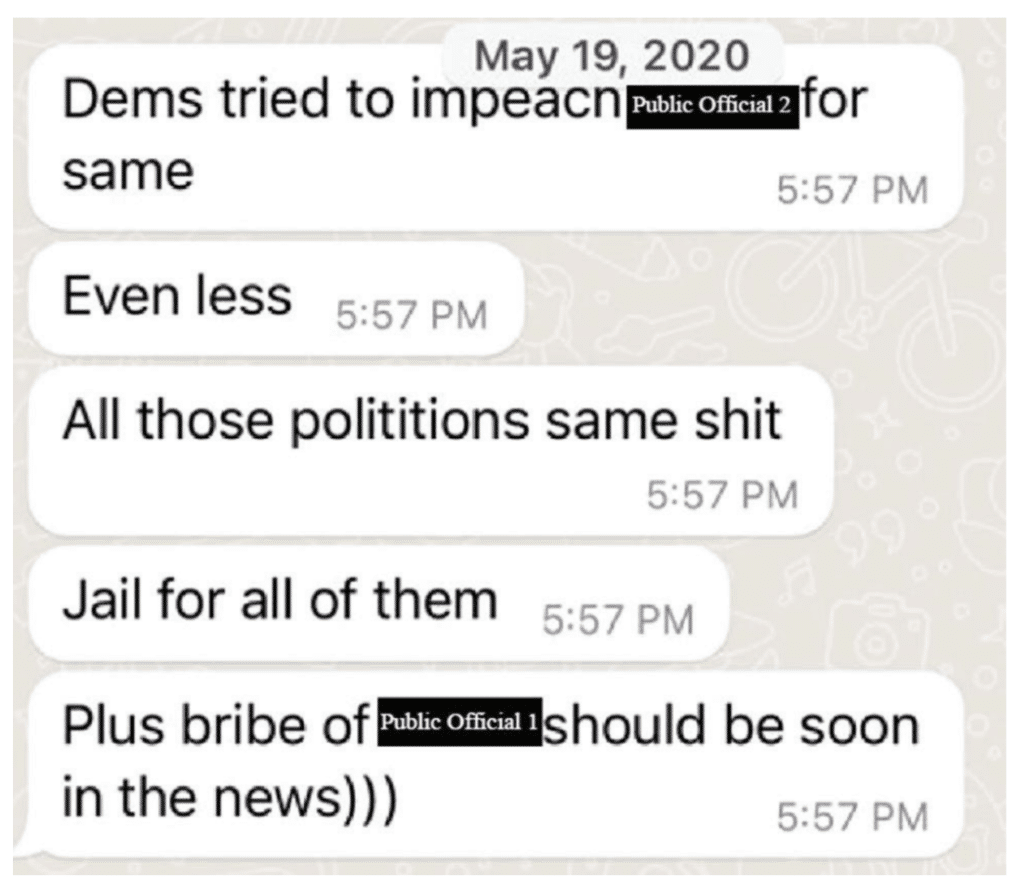

According to the Smirnov indictment, sometime in July (tellingly, Weiss does not reveal whether this preceded his letter to Lindsey Graham, whether it preceded the plea colloquy where Leo Wise reneged on a signed deal), the FBI asked Weiss’ office to help in an investigation regarding the FD-1023.

In July 2023, the FBI requested that the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the District of Delaware assist the FBI in an investigation of allegations related to the 2020 1023. At that time, the United States Attorney’s Office for the District of Delaware was handling an investigation and prosecution of Businessperson 1.

It is virtually certain that the FBI asked Weiss to pursue whether any leads had been missed in 2020, not whether Joe and Hunter Biden had been unfairly framed. That’s because Weiss cannot — should never have — led an investigation into how the Bidens were framed. He’s a witness in that investigation.

So it is almost certain that the FBI decided to reopen the investigation into the FD-1023, perhaps based in part on Bill Barr’s false claims. It is almost certain that this investigation, at that point, targeted Joe and Hunter Biden. It is almost certain that this is one thing Weiss used to rationalize asking for Special Counsel authority.

And that’s probably why, when Weiss’ team interviewed Smirnov on September 27, Smirnov felt comfortable adding new false allegations.

51. The Defendant also shared a new story with investigators. He wanted them to look into whether Businessperson 1 was recorded in a hotel in Kiev called the Premier Palace. The Defendant told investigators that the entire Premier Palace Hotel is “wired” and under the control of the Russians. The Defendant claimed that Businessperson 1 went to the hotel many times and that he had seen video footage of Businessperson 1 entering the Premier Palace Hotel.

52. The Defendant suggested that investigators check to see if Businessperson 1 made telephone calls from the Premier Palace Hotel since those calls would have been recorded by the Russians. The Defendant claimed to have obtained this information a month earlier by calling a high-level official in a foreign country. The Defendant also claimed to have learned this information from four different Russian officials.

Smirnov seemingly felt safe telling new, even bigger lies. In his mind, Hunter and Joe were still the target! Again, that is consistent with the investigation into Hunter Biden being reopened based off Bill Barr’s public pressure.

According to the Smirnov indictment, David Weiss’ team found evidence that proves Bill Barr lied and Scott Brady created a false misimpression — the former, to pressure him — Weiss — and the latter, in testimony to Congress that was also part of the pressure campaign against the Bidens.

Compare Bill Barr’s claim made on the day when Weiss agreed that Hunter would face no further charges with what the Smirnov indictment states as fact. The Smirnov indictment says that Scott Brady’s office closed the assessment, with the concurrence of David Bowdich and Richard Donoghue, which is what Jamie Raskin said (though Raskin said Barr himself concurred).

40. By August 2020, FBI Pittsburgh concluded that all reasonable steps had been completed regarding the Defendant’s allegations and that their assessment, 58A-PG-3250958, should be closed. On August 12, 2020, FBI Pittsburgh was informed that the then-FBI Deputy Director and then-Principal Associate Deputy Attorney General of the United States concurred that it should be closed.

But Barr told the Federalist that it was not closed down, it was forwarded — by Richard Donoghue, days after the President yelled at Barr about this investigation (though he didn’t say that) — to David Weiss for more investigation.

It’s not true. It wasn’t closed down,” William Barr told The Federalist on Tuesday in response to Democrat Rep. Jamie Raskin’s claim that the former attorney general and his “handpicked prosecutor” had ended an investigation into a confidential human source’s allegation that Joe Biden had agreed to a $5 million bribe. “On the contrary,” Barr stressed, “it was sent to Delaware for further investigation.”

Had it been forwarded to David Weiss for more investigation, had he taken those additional investigative steps Barr claims he was ordered to do, Weiss would have discovered right away the key things that proved Smirnov was lying, the claims that Scott Brady had claimed to investigate, the things that the Smirnov indictment suggest he newly discovered months ago.

According to Scott Brady’s testimony to Congress, his team asked Smirnov’s handler about things like travel records and claimed that it was consistent.

Mr. Brady. So we attempted to use opensource material to check against what was stated in the 1023. We also interfaced with the CHS’ handler about certain statements relating to travel and meetings to see if they were consistent with his or her understanding.

Q And did you determine if the information was consistent with the handler’s understanding?

A What we were able to identify, we found that it was consistent. And so we felt that there were sufficient indicia of credibility in this 1023 to pass it on to an office that had a predicated grand jury investigation. [my emphasis]

According to the Smirnov indictment, Weiss’ team asked the handler the same question — about travel records. Only, they discovered that Smirnov’s travel records were inconsistent with the claims the handler himself recorded in the FD-1023.

43. On August 29, 2023, FBI investigators spoke with the Handler in reference to the 2020 1023. During that conversation, the Handler indicated that he and the Defendant had reviewed the 2020 1023 following its public release by members of Congress in July 2023, and the Defendant reaffirmed the accuracy of the statements contained in it.

44. The Handler provided investigators with messages he had with the Defendant, including the ones described above. Additionally, the Handler identified and reviewed with the Defendant travel records associated with both Associate 2 and the Defendant. The travel records were inconsistent with what the Defendant had previously told the Handler that was memorialized in the 2020 1023.

Tellingly, when Brady was asked more specific questions about Smirnov’s travel records, his attorney, former Trump-appointed Massachusetts US Attorney Andrew Lelling, advised him, twice, not to answer.

Q And did you determine that the CHS had traveled to the different countries listed in the 1023?

Mr. Lelling. I would decline to answer that.

[snip]

Q The pages aren’t numbered, but if you count from the first page, the fourth page, the first full paragraph states, following the late June 2020 interview with the CHS, the Pittsburgh FBI Office obtained travel records for the CHS, and those records confirmed the CHS had traveled to the locales detailed in the FD1023 during the relevant time period. The trips included a late 2015 or early 2016 visit to Kiev, Ukraine, a trip a couple months later to Vienna, Austria, and travel to London in 2019. Does this kind of match your recollection of what actions the Pittsburgh FBI Office was taking in regards to this.

Mr. Lelling. Don’t answer that. Too specific a level of detail

Q You had mentioned last hour about travel records.

Did your office obtain travel records, or did you have knowledge that the Pittsburgh FBI Office obtained travel records?

Mr. Lelling. That you can answer yes or no.

Mr. Brady. Yes.

If Brady obtained those travel records, he would have discovered what Weiss did: Neither Smirnov’s travel records nor those of his subsource, Alexander Ostapenko, are consistent with the story Smirnov told.

o. Associate 2’s trip to Kiev in September 2017 was the first time he had left North America since 2011. Thus, he could not have attended a meeting in Kiev, as the Defendant claimed, in late 2015 or 2016, during the Obama-Biden Administration. His trip to Ukraine in September 2017 was more than seven months after Public Official 1 had left office and more than a year after the then-Ukrainian Prosecutor General had been fired.

[snip]

34. Further, the Defendant did not travel to Vienna “around the time [Public Official 1] made a public statement about [the thenUkrainian Prosecutor General] being corrupt, and that he should be fired/removed from office,” which occurred in December 2015.

Paragraph after paragraph of the Smirnov indictment describe how the travel records — the very travel records that the handler and Scott Brady claimed corroborated the allegation — proved Smirnov was lying.

The record is quite clear that Bill Barr and Scott Brady made false representations about activities that directly involved David Weiss in 2020.

And yet Weiss has been playing dumb.

Abbe Lowell made a subpoena request and a discovery request relating to these matters on November 15. Lowell not only laid out this scheme in his selective and vindictive prosecution claim, but he cited the Federalist story in which Barr lied. He cited these matters in his discovery request.

Rather than acknowledging that Weiss’ team had discovered evidence that proved the claims of Barr and Brady were misrepresentations, Weiss’ team lied about the extent of Richard Donoghue’s role — documented in a memo shared by Gary Shapley — in forcing Weiss to accept the FD-1023 on October 23, 2022.

Next, defendant alleges that “certain investigative decisions were made as a result of guidance provided by, among others, the Deputy Attorney General’s office.” ECF 58, at 3 n.4. In fact, the source cited revealed that the guidance was simply not to conduct any “proactive interviews” yet.

And now, on the eve of Abbe Lowell submitting a reply on his motion to compel and a selective prosecution and discovery request in California, David Weiss has unveiled a belated indictment proving that Lowell’s allegations were entirely correct. The indictment may well provide excuse to withhold precisely the discovery materials Lowell has been demanding for months, and it may create the illusion that Barr’s pressure led Weiss to renege on a plea deal. But it is a confession that there was an attempt to frame Joe Biden and his son in 2020.

What David Weiss discovered — if he didn’t already know about it — is that he was part of an effort to frame Joe Biden in 2020, an effort that involved the Attorney General of the United States. If Merrick Garland is going to appoint Special Counsels for these kinds of things, one should be appointed here, especially given that Donoghue required the briefing on the FD-1023 days after Trump personally intervened with Bill Barr.

But David Weiss can’t lead that investigation. He’s a witness to that investigation.

Update: Fixed how long it took Weiss to renege on the deal after Bill Barr’s false claim.

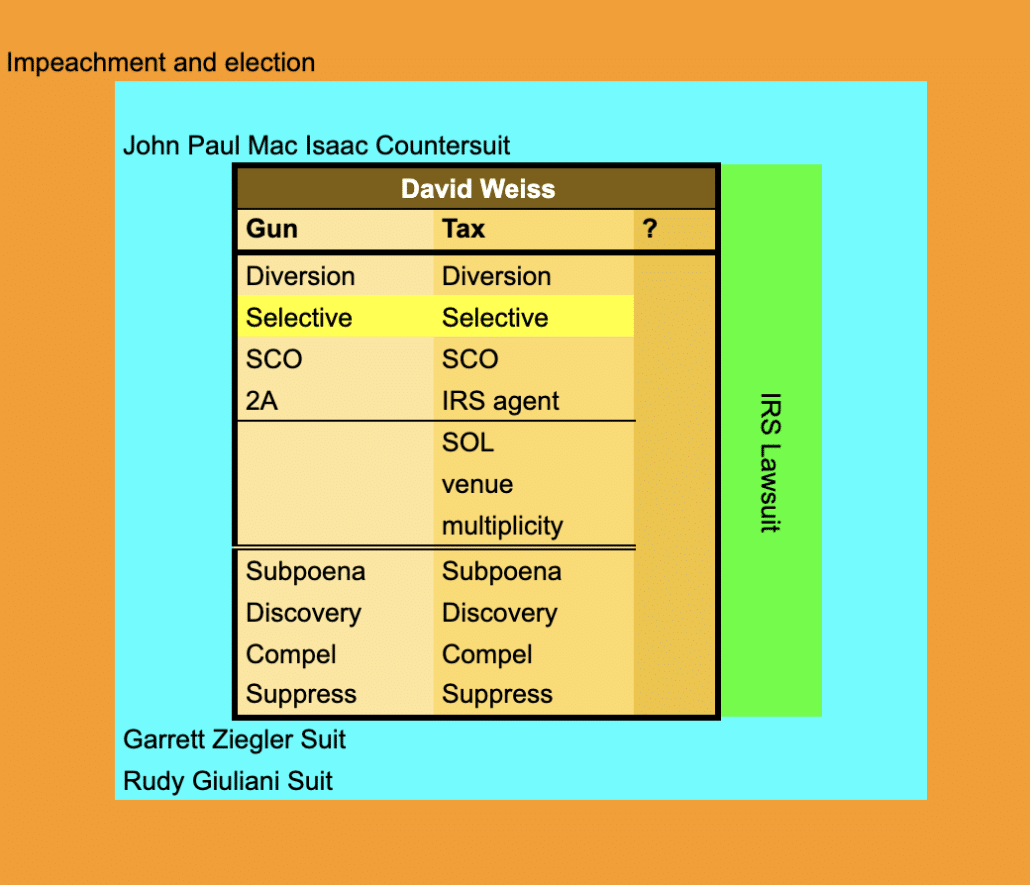

See Hunter Biden’s Eight Legal Chessboards for links to all the filings.