The March 6, 2017 Notes: Proof about Materiality

Update: Read this post on the March 6, 2017 notes before this one.

I want to return to John Durham’s objection to Michael Sussmann’s plan to offer notes from an FBI Agent and notes from a March 6, 2017 meeting as evidence.

The defense also may seek to offer (i) multiple pages of handwritten notes taken by an FBI Headquarters Special Agent concerning his work on the investigation of the Russian Bank-1 allegations, (including notes reflecting information he received from the FBI Chicago case team), and (ii) notes taken by multiple DOJ personnel at a March 6, 2017 briefing by the FBI for the then-Acting Attorney General on various Trump-related investigations, including the Russian Bank-1 allegations. See, e.g., Defense Ex. 353, 370, 410. The notes of two DOJ participants at the March 6, 2017 meeting reflect the use of the word “client” in connection with the Russian Bank-1 allegations.1 The defendant did not include reference to any of these notes – which were taken nearly six months after the defendant’s alleged false statement – in its motions in limine. Moreover, the DOJ personnel who took the notes that the defendant may seek to offer were not present for the defendant’s 2016 meeting with the FBI General Counsel. And while the FBI General Counsel was present for the March 6, 2017 meeting, the Government has not located any notes that he took there.

The Government respectfully submits that the Court should require the defense to proffer a non-hearsay basis for each portion of the aforementioned notes that they intend to offer at trial. The defendant has objected to the Government’s admission of certain notes taken by FBI officials following the defendant’s September 19, 2016 meeting with the FBI General Counsel, and the Government has explained in detail its bases for admitting such notes. Accordingly, the defendant should similarly proffer a legal basis to admit the notes he seeks to offer at trial. Fed. R. Evid. 801(c).

1. The notes of the March 6, 2017 briefing do not appear on the defendant’s Exhibit List, but the Government understands from its recent communications with counsel that they may intend to offer the notes at trial.

As I noted here, attempting to introduce the notes achieves some tactical purpose for Sussmann: presumably, the rules Judge Christopher Cooper adopted in his motions in limine order will apply to these two potential exhibits. So putting these exhibits out there provide a way to hem Durham in on that front.

But they may be more central to Sussmann’s defense. Sussmann may be preparing these exhibits (and one or more witnesses to introduce them) to prove that his alleged lie was not material.

We know a bit about the meeting in question and the potential note-takers.

The DOJ IG Report on Carter Page explains that, after Dana Boente became acting Attorney General after Sally Yates’ firing, he asked for regular briefings because he believed that, “the investigation had not been moving with a sense of urgency,” and that, “it was extraordinarily important to the Department and its reputation that the allegations of Russian interference in the 2016 U.S. elections were investigated.” DOJ IG may have muddled the scope of these meetings (as they did the scope of Bruce Ohr’s actions), because Boente was obviously talking about all the Russian interference allegations, and Alfa Bank was, as far as we know, always separate from Crossfire Hurricane (and in any case never became part of the Mueller investigation).

On January 30, 2017, Boente became the Acting Attorney General after Yates was removed, and ten days later became the Acting DAG after Jefferson Sessions was confirmed and sworn in as Attorney General. Boente simultaneously served as the Acting Attorney General on the FBI’s Russia related investigations after Sessions recused himself from overseeing matters “arising from the campaigns for President of the United States.” Boente told the OIG that after reading the January 2017 Intelligence Community Assessment (ICA) report on Russia’s election influence efforts (described in Chapter Six), he requested a briefing on Crossfire Hurricane. That briefing took place on February 16, and Boente said that he sought regular briefings on the case thereafter because he believed that it was extraordinarily important to the Department and its reputation that the allegations of Russian interference in the 2016 U.S. elections were investigated. Boente told us that he also was concerned that the investigation lacked cohesion because the individual Crossfire Hurricane cases had been assigned to multiple field offices. In addition, he said that he had the impression that the investigation had not been moving with a sense of urgency-an impression that was based, at least in part, on “not a lot” of criminal legal process being used. To gain more visibility into Crossfire Hurricane, improve coordination, and speed up the investigation, Boente directed ODAG staff to attend weekly or bi-weekly meetings with NSD for Crossfire Hurricane case updates.

Boente’s calendar entries and handwritten notes reflect multiple briefings in March and April 2017. Boente’s handwritten notes of the March meetings reflect that he was briefed on the predication for opening Crossfire Hurricane, the four individual cases, and the status of certain aspects of the Flynn case. [my emphasis]

As noted, these meetings focused on ways to “reenergize” the Russian investigations, including the one into Paul Manafort’s corruption.

Additionally, notes from an FBI briefing for Boente on March 6, 2017, indicate that someone in the meeting stated that Ohr and Swartz had a “discussion of kleptocracy + Russian org. crime” in relation to the Manafort criminal case in an effort to “re-energize [the] CRM case.”

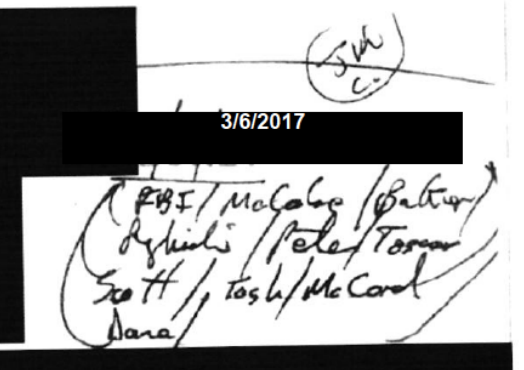

And we know who attended the March 6 meeting, because Jeffrey Jensen released highly redacted notes — with a date added — as part of his effort to blow up the Mike Flynn case.

Jim C[rowell, who took the notes]

FBI/McCabe/Baker/Rybicki/Pete/Toscas

Scott/Tash/McCord/Dana/

For the benefit of the frothers who are sure David Laufman was part of this: sorry, he was not.

Laufman did not attend the meetings in January, February, and March 2017 that were attended by Boente, McCord, and other senior Department officials.

The IG Report describes that in addition to Crowell, Boente, Tashina Gauhar, and Scott Schools took notes of these meetings. We also know Strzok was an assiduous note taker, so it’s likely he took notes as well. People like Crowell (who is now a Superior Court judge) or Boente would make powerful witnesses at trial.

And according to Durham’s objection, among the as many as five sets of notes from this meeting that James Baker attended, two say that the word “client” came up in conjunction with the Alfa Bank allegations.

Durham seems to suspect this is an attempt to bolster possible Baker testimony that, after the initial meeting between him and Sussmann, he came to know Sussmann had a client (which would be proof that Sussmann wasn’t hiding that). He did, and within days! That’s one important part of the communications during which Baker got Sussmann and Rodney Joffe’s help to kill the NYT story: as part of that exchange, he learned that Sussmann had to consult with someone before sharing which news outlet was about to publish the Alfa Bank story. For that purpose, according to the common sense rules just adopted by Cooper, one or some of the ten people at the meeting would need to remember Baker referring to a “client,” and one of the two people who noted that in real time has to remember doing so.

But there’s likely another reason Sussmann would want to introduce this information.

Not only did a contemporaneous record reflect that everyone involved learned if they did not already know that there was a client involved in this Alfa Bank allegation, but by then everyone involved also knew that Glenn Simpson worked first for a GOP and then a Democratic client.

Finally, handwritten notes and other documentation reflect that in February and March 2017 it was broadly known among FBI officials working on and supervising the investigation, and shared with senior NSD and ODAG officials, that Simpson (who hired Steele) was himself hired first by a candidate during the Republican primaries and then later by someone related to the Democratic Party.

The things that, Durham insists, would have led the FBI to shy away from this investigation were known by the time of this meeting.

And, I suspect, that’s why Sussmann wants to introduce the FBI Agent’s notes (and yes, it is possible they are Strzok’s). Because the actions taken in the wake of this meeting provide a way of assessing what the FBI would have done — and did do — after such time as they undeniably knew that Sussmann had a client.

Boente wanted more action taken. Ultimately, whatever action was taken led shortly thereafter to the closure of the investigation.

But Durham’s entire prosecution depends on proving that the FBI would have acted differently if they knew Sussmann had a client. So it is perfectly reasonable for Sussmann to introduce evidence about what the FBI said and did after such time as they provably did know that.

Finally, clarification on the materiality front. Thank you, Dr. Wheeler–I’ve been waiting for this (rebuttal? pre-buttal?) evidence for a long time. I would love to see Strzok’s notes on this issue, on non-issue as it seems to have been.

This accrues to the portrait of Durham taking shape through your posts: the entire enterprise exists for the purpose of spinning off scraps, which rightwing media can dress up in a pantsuit and present as “proof” of a conspiracy.

Drawing the process out as long as possible might be Durham’s best strategy, for the sake of keeping the myth going through midterm elections.

To be clear, I think Sussmann has a good materiality argument in any case. Always remember that Durham didn’t bother chasing down whether or not he really did provide this info to give the FBI maximal options. It does real damage to Durham’s claims of materiality.

Publicity is the point, not prosecution and FWIW it seems doubtful to me that Durham and DeFilippis will get this dragged out to November if voir dire questions are being discussed (IIRC, but IANAL).

On a prior post the adventures of James O’Keefe and Project Veritas were covered. While these are defendants, the beginning statement remains the same.

It’s what allows for the filing of ridiculous claims without any real evidence, in order to keep the RWNM primed with sound bites.

Doesn’t it seem that if the FBI were truly misled into the investigation by the original statement, the appearance of the word, “client,” would be cloaked with a little more concern/shock/”wait ’til we get our hands on that lying SOB”? I guess I’m saying it doesn’t appear to be a surprise, and wouldn’t it have to have been–at least at some point–to have been “material”? I wouldn’t be surprised if Durham was hiding notes that reflect the FBI’s awareness of Sussmann’s atty-client relationship(s) where an attitude of”no shit, Sherlock” was the reaction.

Can anyone explain how materiality works in a trial like this in terms of burden of proof?

Is it likely that Durham will have a major challenge in establishing to the satisfication of a jury that the statement was material? Or is it more likely that the defense will need to go to great lengths to show that it was not?

I realize a lot depends on the composition of the jury, but my understanding is that a lot of times as far as white collar fraud cases it’s been very challenging for prosecutors to prove intent, and simply showing that someone made certain financial transactions is often insufficient.

Is there a parallel situation here where Durham is going to need to work hard to prove materiality? Or is reality that the defense will have to work hard to prove it was not?

You play the cards you’re dealt with. Certainly, “I’m innocent of the crime because I never lied” may be a stronger defense than “I’m innocent of the crime despite lying because the lie was just a little white one that never hurt anyone.”

Materiality is an element of the crime, so it’s fair game. Durham has to prove the materiality impact as part of the case, otherwise Sussmann could likewise file to dismiss case because prosecutors failed to prove any crime occurred.

If this is only place Sussmann can chip away, then chip away he must.

This.

More to the point, has Durham produced a shred of evidence of actual materiality? Not speculation and generic statements with no connection to the particular case that it MIGHT be material, because gee whiz–the FBI has limited resources and has to triage its tips, and of course the potential motives of an informant could inform those decisions, but actual notes–or better, witness testimony–from someone in the Bureau involved with the case that “if we only had known he was Hillary’s lawyer, we would have put this on the bac burner?”

I don’t see anything that demonstrates that the FBI was hoodwinked or otherwise harmed by any of these, even if we were to stipulate that Sussman was knowingly lying through his teeth.

And if the best the prosecution has is general claims of “of course it’s material; anything could be”–would that survive a motion for summary judgment? While Judge Cooper has said materiality must be decided by the jury, one would think/hope that there might be a minimum standard of evidence, particular to the case at hand, that must be satisfied to satisfy the “reasonable jury” standard; and that trying to win this case with no actual evidence of one of the required elements of the crime, just speculation, would get tossed out before the jury gets to deliberate.

There will be a significant fight over the definition of “material” in jury instructions, but the two elements in the DC Circuit will come in:

And from there it’s up to the jury.

The standard is very low.Sussmann is just trying to assemble to rebut Durham’s arguments from sympathetic FBI agents.

As I said in another post, Baker’s role was as recipient and then to distribute the Sussman material to the proper FBI cyber experts. To my knowledge, he had no role in assessing the info. Does he act any differently depending on what Sussman did or didn’t say about a client? Is there a memo or document by Baker that accompanied the Sussman data that in any way references the remark about clients?

Were the FBI cyber experts briefed on whether or not Sussman said something about a client? How is their analysis of the meaning of the data affected in any way about what Sussman said to Baker about clients?

I understand Durham’s assertion that allegedly Sussman’s alleged remarks affected how the FBI did its job, but that assertion is not evidence. Someone has to testify as to how it affected the FBI’s examination of the data. What is the alleged proof that it affected the FBI examination of the DNS data?

Exactly. Where’s the paperwork upon which Durham is basing his case? For this to go forward, (were I the judge) I’d want to see notes taken by someone who was at Sussman’s meeting with Baker. Was the question asked? Was it answered? If it wasn’t asked is this something Sussman would have been legally required to volunteer?

Once again, I don’t see a case.

Eh, that is what trials are for.

I thought Baker took no notes at the time of the meeting and only gave his recollection of the meeting after the fact to someone else in the FBI.

Materiality, National Security tip, client representation…..none of that will matter in the end.

Once the jury finds out Sussmann was working for the Hillary campaign when he gave Baker the Alfa docs his fate is sealed. If Durham is also able to tell the jury that Sussmann consulted with Fusion GPS, Christopher Steele and many news outlets before the FBI, then its over even quicker.

The jury is not dumb, they know the HRC campaign made a concerted dirty tricks effort to tie Trump to Russia and Sussmann’s questionable reach out to the Bureau was just more of the same.

Is it dirty tricks if it is true? Trump seems to believe telling the truth about him is worse than lying because lies are his common currency. His own kid gave up the Russian connection in an interview. It is public knowledge Trump and Putin have interacted in suspicious circumstances.

That only works if Durham is able to seat 12 Durham clones. How likely do you think that is? I would say about as likely as Sussman being able to seat 12 Sussman clones. To repeat: working for a political campaign is not a crime, and juries are given instructions on how to assess what they are being told.

Even the sort of ratfucking operation that Pedro alleges took place, is not a crime.

Eh, neither side ever gets that and, yet, juries very rarely hang up. So, I would expect a verdict, and we shall see how it goes.

Not a persuasive argument, unless you’re addicted to watching Faux Noise.

Pedro:

If I didn’t assume you were a troll who can’t read, I would assume you’ve read nothing that appears in recent posts, including something that lays out what can and cannot come in, much less a description of what the evidence actually shows.

We don’t mind smart trolls here. But stupid ones? Nuh uh.

Lol.

Just for the record, I can read and I think I am a troll.

I have not read every post about what might be allowed for evidence but I gotta believe that the prosecutor will be able to say to the jury that Sussmann worked for and billed the HRC campaign when he met with Baker. I also think that the jury will hear that there is a discrepancy about whether or not Sussmann told Baker that he was representing a client.

In my post, I said when the jury hears that, they will suspect that he lied, so it wouldn’t look like he was peddling opposition research.

-Just my opinion-.

Plus, if the jury hears, oh, he lied but it wasn’t material, that too will not be well received.

– just my opinion-.

The other stuff in my post about Steele, Fusion and the press I prefaced with an “if”.

If that makes me a stupid troll, lmk and I’ll move along.

You did not make a “post” you made a comment, there is a difference. And, yes, you are a troll and now you are annoying me too. Marcy is the nice one here. I would not “vote for Pedro” at this point.

Oh, and by the way, I do not think you understand dick about evidence, criminal elements or jury trials.

The jury WON’T hear that he billed Hillary for the meeting.

He didn’t bill anyone for the meeting. You’re badly misunderstanding the evidence in this case. Better just reading more than trying to make your conclusions before doing that.

Bzzt wrongo what are you even doing here

The trial will take place in the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia.

You tell me – where is Durham going to find a pool, much less a panel with 12 Hillary hating trumphumpers in Washington D.C?

Don’t feed the trolls!

So Sussman’s defence is

(a) he never lied about not having a client, but

(b) if he had lied, it wasn’t material/influential

But is (b) actually a defence? I thought I’d read that the materiality of the lie was only important to whether the jury chooses to convict (ie that the lie was not important enough to convict someone of a crime). Could the jury still find Sussman guilty even if he proves beyond doubt that his lie had no impact on any FBI decision?

Note, I’m not saying he did lie. I’m asking if that’s the only question that a jury needs to find beyond reasonable doubt for a conviction.

Absolutely. And an extremely common and well grounded defense.

Then Durham really must have been smoking something to bring this charge :)

Thanks for the answer. Sorry for asking such a basic question. I still can’t get my head around what Durham hopes to gain by this nonsense, but he must believe that providing so much material for rightwing conspiracy promoters must be an end in itself. There seems no other point at all.

That’s the thing though, you never know what happens in a trial. And what people think is “evidence” now may or may not be at the actual trial. Things change. Both sides have to make their case. But, yes, it is a legitimate defense. Every element of a crime, and materiality is one for this one, is a legitimate defense point.

He also likely views it as tactical–a way to move closer to the conspiracy case he wants to charge. And on that front he may be successful.

But Durham has not. He is rumbling, bumbling and stumbling toward a trial on a single podunk §1001 charge. You never know, but courts pretty much historically frown on serially dribbling out charges that could have been brought to start with. And Cooper would likely get any next assignment.

But what is the conspiracy case that he wants to charge? As noted elsewhere, “opposing Trump’s candidacy for office” is not illegal; none of the principals in this case have any duty to be neutral, and the only potentially-illegal acts that I’m aware of Durham uncovering, the alleged Sussman lie being the main one, are remotely significant enough to hang a conspiracy charge on.

The only illegality Durham has identified is the alleged lie to the FBI, which he has to prove happened and was material. He has a long row to hoe on both counts. Basically, Durham has squat.

Note that attacking all elements that the prosecution must prove is a standard, accepted, and honorable tactic for the defense.

By attacking materiality, nobody involved in the trial (and the judge will make this clear to the jury) will assume that the defense is conceding that Sussman lied.

If Sussman takes the stand in his defense and testifies, under oath, that he said nothing about the topic on 1/19, Durham will have a hard time rebutting this. It would probably require the prosecution to call Baker and for Baker to say, “no, you told me to my face that you were working for nobody”; I don’t think the judge would allow grand jury testimony (not subject to cross-examination) or third-party notes with slightly dubious provenance to overrule direct testimony by a live witness in court. And the fact that Baker has apparently told different people different stories (not surprising if this is a minor detail he doesn’t remember, and he got pressured into answering a question that he was unsure of the answer of) could be used to attack his credibility; either party would be able to do so were he to take the stand.

Of course, calling the defendant as a witness has its own risks, and the defense would probably prefer to win the case without doing so.

“calling the defendant as a witness has its own risks”

I know that’s true generally, but is it that risky when your defendant is an accomplished, experienced lawyer who isn’t hiding anything?

Yes, it is always true.

It’s a hell of a system when even an innocent defendant is best advised not to give evidence in his own defence :(

Naw, that is a fine system. The client has the final say, and that is appropriate. Lawyers are horrible clients (trust me), so, yeah, he isn’t taking the stand unless absolutely necessary. We’ll see how the trial goes, but it may well be necessary in this case. The defense does not have to decide that until the end of the case though.