Thirty Months after Disputing Michael Horowitz, Durham’s Team Suggests They’ve Never Looked at the Evidence

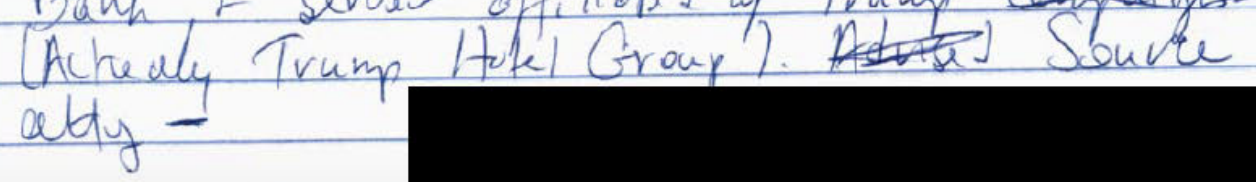

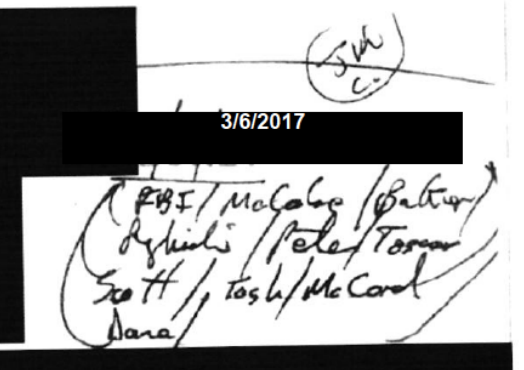

In Michael Sussmann’s filing explaining that he couldn’t include highly exculpatory notes — written by Tashina Gaushar, Mary McCord, and Scott Schools — from a March 6, 2017 meeting in his motion in limine because John Durham had provided them to him too late to include, Sussmann claimed that the files were not among those for which Durham had gotten permission to provide late.

The Special Counsel neglects to mention that these handwritten notes were buried in nearly 22,000 pages of discovery that the Special Counsel produced approximately two weeks before motions in limine were due. Specifically, the Special Counsel produced the March 2017 Notes as part of a March 18, 2022 production. The Special Counsel included the March 2017 Notes in a sub-folder generically labeled “FBI declassified” and similarly labeled them only as “FBI/DOJ Declassified Documents” in his cover letter. See Letter from J. Durham to M. Bosworth and S. Berkowitz (Mar. 18, 2022). And although the Special Counsel indicated on a phone call of March 18, 2022 that some of the 22,000 pages were documents that made references to “client,” he did not specifically identify the March 2017 Notes or otherwise call to attention to this powerful exculpatory material in the way that Brady and its progeny requires.

[snip]

[T]he Special Counsel has also failed to explain why this powerful Brady material was produced years into their investigation, six months after Mr. Sussmann was indicted, and only weeks before trial.3

Sussmann was wrong.

When Durham got an extension to his discovery deadlines, he got special permission to turn over (among other things) materials from DOJ IG at a later date.

DOJ Office of Inspector General Materials. On October 7, 2021, at the initiative of the Special Counsel’s Office, the prosecution team met with the DOJ Inspector General and other OIG personnel to discuss discoverable materials that may be in the OIG’s possession. The Special Counsel’s office subsequently submitted a formal written discovery request to the OIG on October 13, 2021, which requested, among other things, all documents, records, and information in the OIG’s possession regarding the defendant and/or the Russian Bank-1 allegations.

[I]n January 2022, the OIG informed the Special Counsel’s Office for the first time that it would be extremely burdensome, if not impossible, for the OIG to apply the search terms contained in the prosecution team’s October 13, 2021 discovery request to certain of the OIG’s holdings – namely, emails and other documents collected as part of the OIG’s investigation. The OIG therefore requested that the Special Counsel’s Office assist in searching these materials. The Government is attempting to resolve this technical issue as quickly as possible and will keep the defense (and the Court as appropriate) updated regarding its status.

In the pre-trial hearing on Monday, Andrew DeFilippis explained that the files came from DOJ IG (and therefore were subject to that later discovery deadline).

We located those statements in the notes in February or early March, when we received a huge production from the DOJ Inspector General’s office. As soon as we noticed that in the notes, we put them on very rapid declassification at the FBI and turned them over to the defense about a week later.

DeFilippis offered an unconvincing excuse for burying belatedly provided Brady material two layers deep in file folders without specific notice. He described the decision to flag the materials as an internal Government decision, which is an odd description unless Michael Horowitz’s office — or those involved in declassifying the records — forced the decision:

We then, speaking internally as the Government, decided it would be important to flag those notes for the defense. And so the day that we produced them, we got on a call. We wanted to be in a position to flag it in a way that we didn’t just put it in the end of a paragraph of a discovery letter. We flagged for the defense that we were going to be producing notes and that that included notes in which the word “client” appeared. And we told them that we thought that would be relevant to them.

[snip]

Let me just say that there was absolutely no effort by the Government to delay here or to hide these in a large production. That is precisely why we got on a phone call and flagged it for the defense.

It’s almost like DeFilippis was hoping this would get no notice.

I can understand why. I’ve described how astounding it was that Durham did not go looking for evidence from DOJ IG until — by Durham’s own telling — October 7, more than two weeks after indicting Sussmann (and likely not long enough before indicting Igor Danchenko to learn key details that undermine at least one charge against him).

But this late provision of exculpatory evidence means one of two things:

- Durham has always had the files, but did such a poor job of looking for it in discovery he didn’t find it in his own files even as he started hunting Michael Sussmann

- Durham never had these files

The latter is the more likely possibility, which, as a threshold matter, would mean Durham never reviewed key files that DOJ IG had used in high level witness interviews before disputing Michael Horowitz’ conclusion that the investigation was predicated appropriately. Durham is, literally, only reviewing key files three years into his investigation.

Along the way, he’s learning that conspiracy theories he has been chasing for months and years are false.

The revelation that Durham is discovering exculpatory information in DOJ IG’s files is as important to the efforts to blow up the Mike Flynn prosecution two years ago as it is to the Sussmann prosecution. That’s because the Jeffrey Jensen review of the Flynn prosecution and the Durham investigation were believed to be closely aligned. Indeed, I have shown that the handwritten notes from the FBI that Durham will rely on at trial show the same markers of unreliability that documents that were altered in the Flynn case had.

As I explained in this post, Jensen’s documents started with the Bates stamp used throughout the Flynn prosecution.

But after a period of time, they used a Bates stamp with a different typeface, albeit continuing the same series, suggesting someone else was doing the document sharing.

But if they’re drawing on the same source documents, Durham should at least know notes of that meeting exists. Jeffrey Jensen received and relied on at least one set of notes — Jim Crowell’s notes — from the March 6, 2017 meeting. Those notes, along with Tashina Gauhar’s notes of an earlier briefing and all those that got altered, also have the fat typeface.

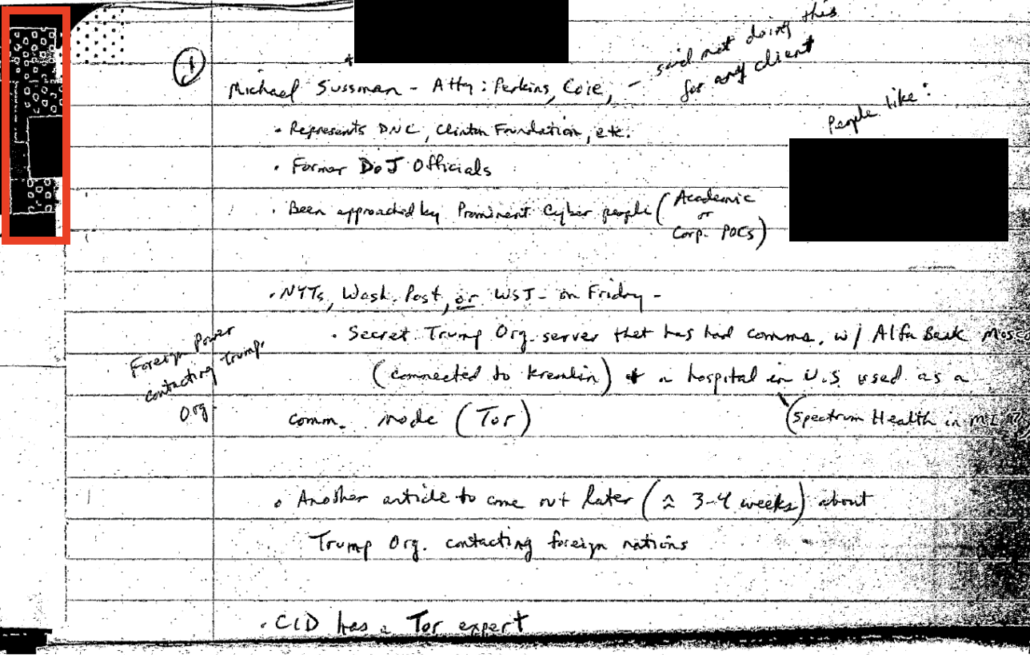

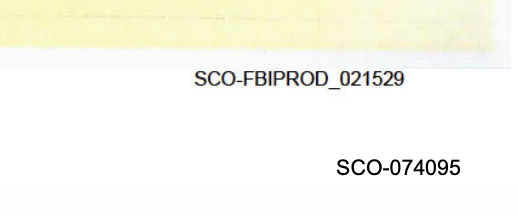

The Tashina Gauhar notes turned over to Sussmann (and the others turned over) not only are based off a scan of her original notes and have no post-it notes on them, but they bear both Durham’s Bates stamp (SCO-074095), but also one that likely comes from DOJ IG (SCO-FBIPROD_021529).

All of which seems to suggest there was the same cherry-picking that went into the Durham investigation and the Jensen “review.” Neither reviewed — neither could have!! — what really happened. They reviewed selected records and then (in the Jensen review) altered those records to make false claims that the former President used in a debate attack.

I’ll come back to the issue of what appears in the notes Sussmann released that conflicts with the Flynn releases.

But I’m also interested that Durham is stalling on providing other notes from the meeting.

2 The defense has requested that the Special Counsel search for any additional records that may shed further light on the meeting and certain of those requests remain outstanding. To date, the Special Counsel has represented that the only additional notes from attendees at the meeting that he has identified do not reference whether or not Mr. Sussmann was acting on behalf of a client. The absence in those notes of any reference to whether Mr. Sussmann was acting on behalf of a client also raises questions regarding materiality of the charged conduct: if the on behalf of information were truly material to the FBI’s investigation, presumably all note takers would have written it down. [my emphasis]

Durham can’t be withholding notes because they don’t mention Sussmann having a client. That’s because Scott Schools’ notes mention that the Alfa Bank tip came from an attorney, but don’t mention that he was there on behalf of a client (Schools’ notes may have been included because they are the only ones of the three provided that attributed this discussion to Andy McCabe).

There are at least two other sets of notes from this meeting that are known or presumed to exist:

- Jim Crowell

- Peter Strzok

And there were at least three other people present at the meeting known to take notes:

- Bill Priestap

- Andy McCabe

- Dana Boente

Importantly, in Durham’s objection to admitting these notes as evidence, he makes it clear that James Baker (inexcusably as a lawyer) did not take notes of this or any other meeting, but he does not say whether Priestap (or Trisha Anderson) took notes.

Moreover, the DOJ personnel who took the notes that the defendant may seek to offer were not present for the defendant’s 2016 meeting with the FBI General Counsel. And while the FBI General Counsel was present for the March 6, 2017 meeting, the Government has not located any notes that he took there.

If Priestap took notes, one copy should be in Durham’s possession, in the notebook of Priestap’s notes already on Durham’s exhibit list.

DOJ has been trying to prevent anyone from looking at Andy McCabe’s notes for some time.

But one thing that turning over the DOJ IG retained notes for the others will show is whether alterations in the Strzok, Priestap, and McCabe notes were made.

It’ll also make it easy to test why Jensen’s review redacted a date and added one — albeit the correct one — in the Jim Crowell notes.

That is, I wonder if Durhams’ reluctance to turn over those materials stems not from any facts about his own investigation, but from an awareness of the cherry-picking — and possibly worse — that having turned over the past one reveals.

Three posts on the altered documents from the Mike Flynn case

The Jeffrey Jensen “Investigation:” Post-It Notes and Other Irregularities (September 26, 2020)

Shorter DOJ: We Made Shit Up … Please Free Mike Flynn (October 27, 2020)

John Durham Has Unaltered Copies of the Documents that Got Altered in the Flynn Docket (December 3, 2020)