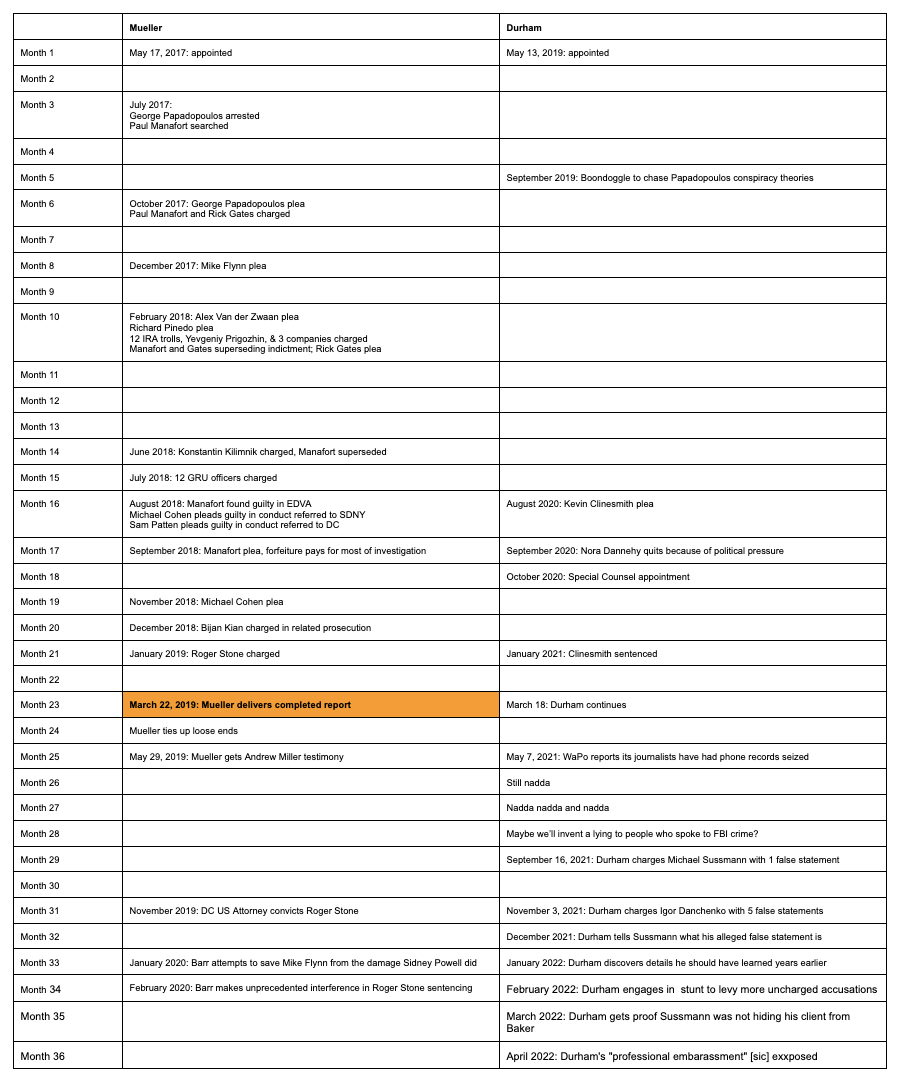

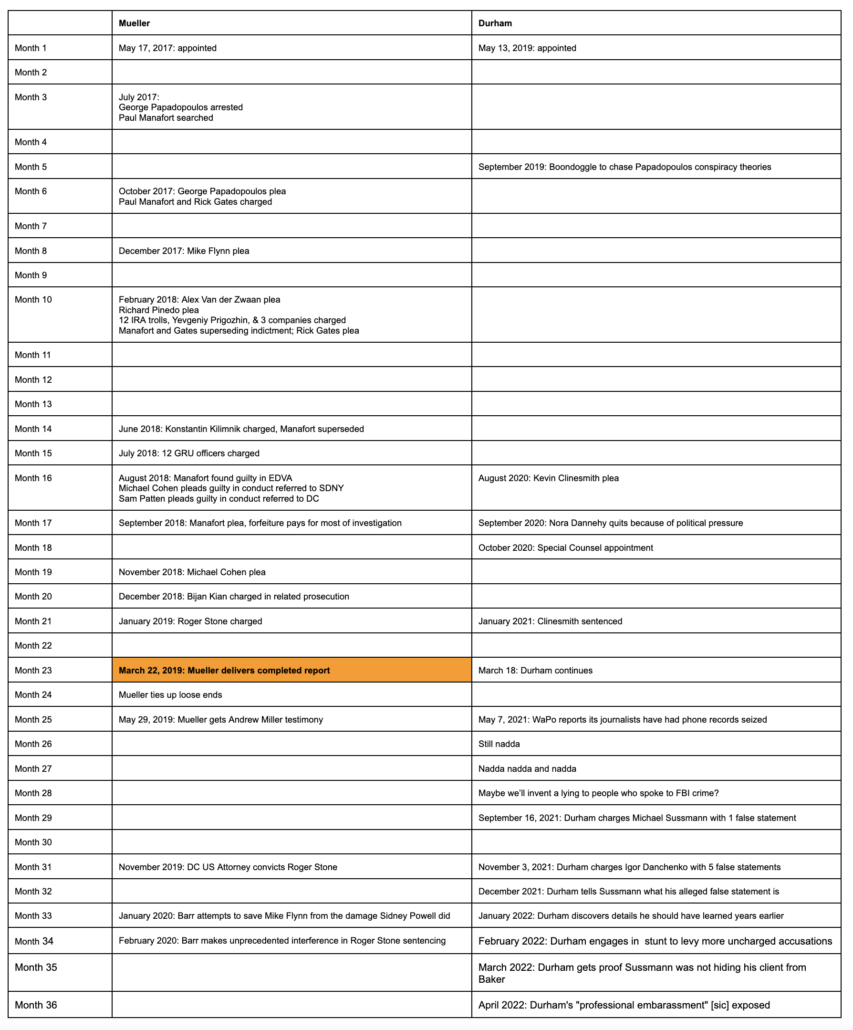

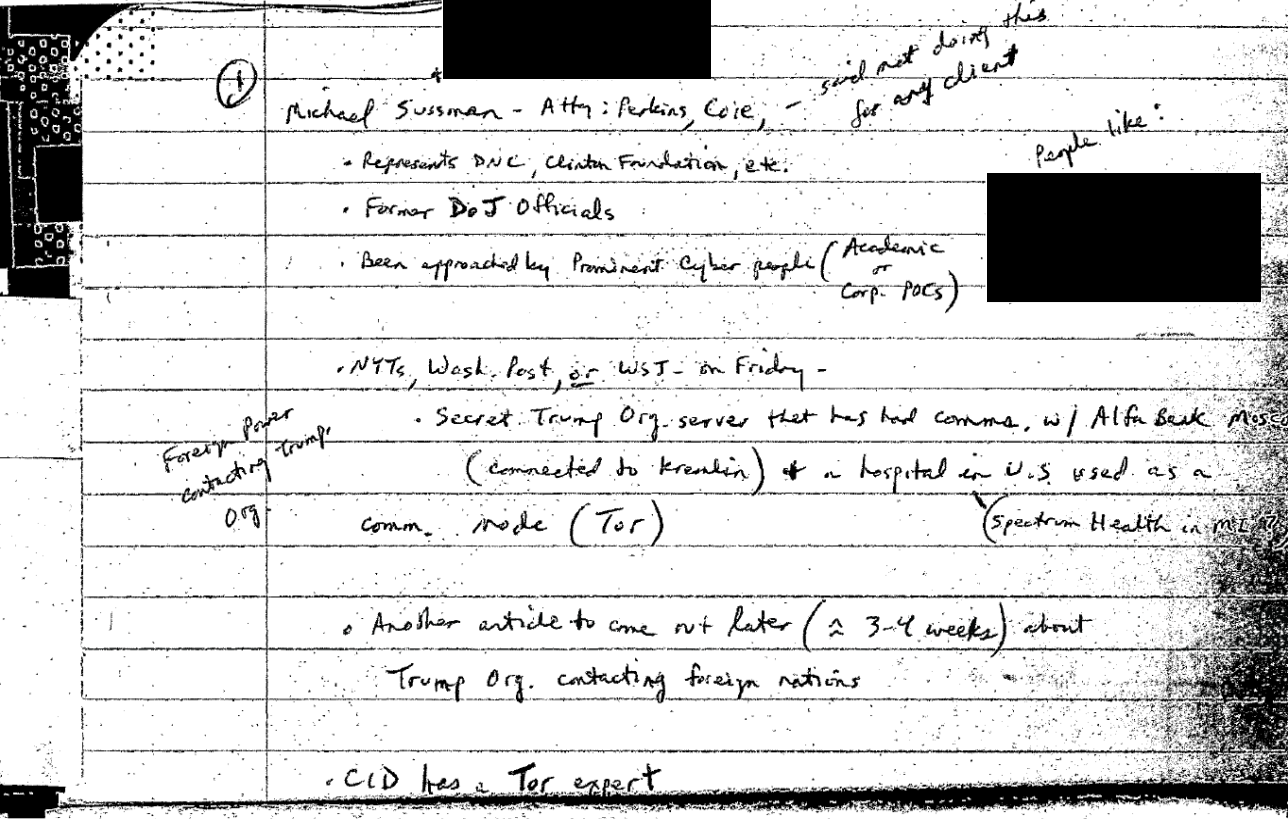

There have been a slew of developments in the Michael Sussmann case, and in advance of two of them, I wanted to lay out what the posture of the case is. One thing that those swooping in for the conspiracy theories seem to miss is that what happens between now and the trial — scheduled to start on May 16, though Durham is trying a number of stunts to delay it — will be dictated by a bunch of rules, and no matter how guilty or innocent or sleazy-but-not-criminal you think Sussmann is (and I think one can make the case for any of the three), the evidence the jury will see will be decided in the next few weeks according to the rules of criminal procedure.

The questions to be decided in the next few weeks are, generally, the following:

- Whether to penalize Durham for breaking the rules

- Whether the Alfa Bank DNS anomaly is real and whether the inferences about it are reasonable

- Whether Judge Christopher Cooper will review privilege claims

- How much of Durham’s conspiracy theories will be admitted

- Whether to immunize Rodney Joffe

Whether to penalize Durham for breaking the rules

A question that won’t be decided until after a status conference next Friday, but which dictates the answer to many of the others, will be whether John Durham will be penalized for ignoring deadlines and other rules. To a greater or lesser degree, even after getting an extension on his discovery and CIPA deadlines, Durham blew off the following deadlines without asking for permission:

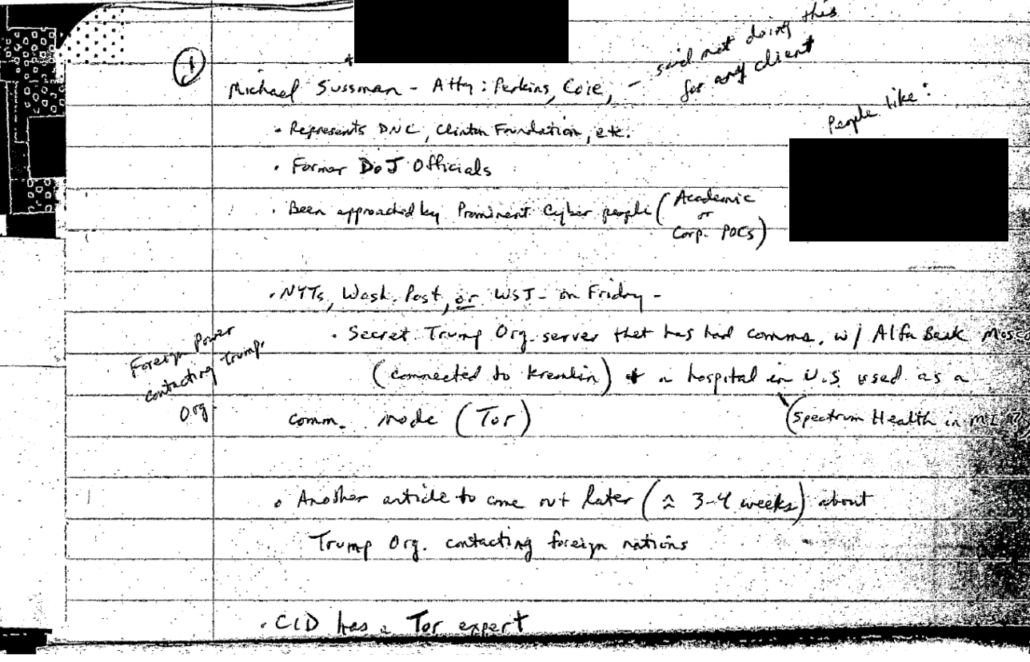

The identity of his expert testimony and the scope of his testimony: In this case, Durham didn’t blow off a hard deadline imposed by Cooper, but he broke the rules of comity by ignoring repeated requests for a description of his use of expert testimony and, thus far, providing only cursory description of what his expert, Special Agent David Martin, will testify to. Durham has tacitly admitted he didn’t provide this in timely fashion; his defense of Martin stated, “the Government intends to provide defense with a supplemental disclosure regarding his training and experience with DNS and TOR.” That description is what should have been provided to Sussmann months ago, so he could find a better expert — and with all due respect to the investigative expertise of Martin, there are far better qualified experts out there.

According to Durham’s filing, Martin has not tried to replicate the DNS anomaly, nor does it appear he plans to, which is the basis every other expert has used to test theories about the anomaly. Further, as Durham describes it, Martin will explain the sources of DNS data generally, not the DNS data available to the various researchers who worked on the anomaly. This latter point is a big tell, because Durham has made all sorts of misleading claims about the sources of the data.

There will, undoubtedly, be some kind of expert to explain what DNS and Tor are; Cooper has said he needs that information himself. But Cooper would be in his right to use Durham’s late notice to limit Martin’s testimony to those topics. Some of this is likely to get decided in a hearing today, so Sussmann can get an expert of his own accordingly.

404(b) notice for two claims: Durham submitted one 404(b) notice (of evidence he’d like to submit but which may not be direct evidence of a crime) in timely fashion, on March 18. It was very cursory, but it listed 4 topics he wanted to introduce:

- Sussmann’s February 9, 2017 meeting at the CIA

- Perkins Coie’s 2018 statements to the press about Sussmann’s meeting with James Baker

- Sussmann’s 2017 testimony about the meeting to HPSCI

- Durham’s now disproven accusation that Sussmann got rid of texts he was required to keep under Perkins Coie’s retention policy

But then, five days later, Durham submitted what he called a “supplement.” That expanded the description — and with the expanded description, expanded the scope — of the four topics he had already noticed, and then added two more:

- The origins of the data

- Evidence about whether the inferences researchers made about the data were reliable

Those last two topics failed to meet Cooper’s deadline, and he could reject their admission on that basis alone.

Communications over which Sussmann’s clients claimed privilege: Sussmann’s opposition to Durham’s effort to pierce privilege lists three rules Durham broke when he told Sussmann a month before trial he wanted to pierce privileged communications:

- A failure to meet either Durham’s original discovery deadline or his expanded one

- A failure to go through Beryl Howell as part of the (secret) grand jury investigation

- Use of a grand jury to get evidence on an already-charged indictment

Normally, such privilege fights take place over the course of months (like the thus far four months that January 6 Committee has been trying to get John Eastman’s documents over which he has made weaker privilege claims or the year that SDNY spent doing a privilege review of Rudy Giuliani’s devices). Here, Durham attempted to pull a stunt to find a way to do this at the last minute. Cooper even called him out for that stunt, noting that this effort requires a motion to compel, not the motion in limine Durham claimed he was going to use. And Cooper called him out (after putting Durham on notice in response to his inflammatory conflicts motion earlier this year), before being presented with the other ways Durham has abused process in an attempt to pierce privilege claims on the eve of trial. While the third of these is less serious than the other two (Durham will claim he was investigating additional crimes), Cooper could deny Durham’s entire effort based on these rule violations.

Whether the anomaly is real and whether the inferences about it are reasonable

Sussmann has argued that the only thing that matters to the false statement charge against him is his own state of mind of whether the anomaly was real and the inferences in the white papers he shared were reasonable. Durham is using a variety of late-hour tactics to insinuate both the anomaly itself and the inferences drawn from it were a set-up designed to impugn Trump. Importantly, he appears to want to do so not by calling the various researchers who found the inferences reasonable, but instead to talk about what other people looking at other (and usually, far less) data thought of it. He is attempting to do this in three ways:

- Introducing hearsay documents to which Sussmann was not a party

- Asking his late-notice expert to talk about the topic without having done the research to address it

- Calling FBI and CIA witnesses, who also did not replicate the claims, to ask their opinions about it

One way Durham could get to this is by calling Rodney Joffe. He’s literally the only one who would know whether he, Joffe, believed the data were reliable and asked Sussmann to share it believing it represented a national security threat, or whether he knew it was a cock-up and cared more about getting Donald Trump investigated. Joffe is also far more expert than Special Agent Martin. But to do that, Durham would have to immunize Joffe, and he is refusing to do that.

Sussmann has raised really good reasons why the way Durham wants to present the question of the reliability of the data is not only irrelevant to his own state of mind, but also violates rules of criminal procedure. Cooper could reject at least some of these efforts based on those rules. And he could put real limits on these claims at a hearing today.

Whether Cooper will review privilege claims

Right now, Durham has only asked Cooper to review privilege claims behind a bunch of documents he wants to enter, though if Cooper were to do that, it would delay the trial considerably (which may be part of Durham’s intent). If Cooper did review the documents, then there’d be a separate fight about whether the documents are admissible in this trial.

But given the explanations in the court filings, most of the communications in question are totally irrelevant to the false statement charge against Sussmann. Many would count as hearsay, inadmissible unless Cooper accepts Durham’s claims that this amounts to a (legal) conspiracy. Just four — communications with Fusion’s Laura Seago — involve Rodney Joffe, the one person who could speak to Sussmann’s own understanding of the reliability of the data. And many if not most of the documents post-date the date of Sussmann’s meeting with James Baker. So in addition to Durham’s rampant rule violations in making this request, Cooper could reject the effort (at least with respect to most of the documents) based on procedural reasons.

How much of Durham’s conspiracy theories will be admitted

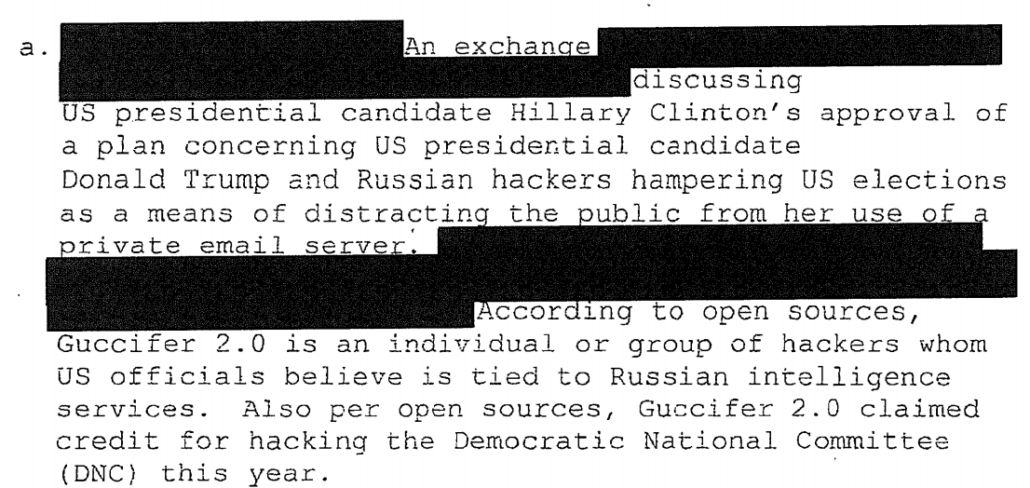

Under the guise of proving a motive wholly incompatible with the now proven willingness on the part of Sussmann and Joffe to help the FBI kill the NYT story, Durham wants to treat the Democrats’ parallel efforts (the Steele dossier and the Alfa Bank anomalies) as one giant conspiracy.

He has not alleged that the conspiracy, if true, amounts to a crime. Indeed, he has ignored that many of the suspicions that he points to as proof of maliciousness — suspicions that Paul Manafort was laundering money from Oligarchs close to Putin, suspicions that family members of Alfa Bank Oligarchs were helping Manafort launder those relations, suspicions that Trump had secret communications directly with the Kremlin — all turned out to be 100% true.

Durham’s ability to make this argument at all really pivots on Joffe’s claims about his relationship with Fusion; he says it was not one of common interest but instead consulting work through Sussmann. That’s undoubtedly the sketchiest claim in this entire house of cards (and because of Joffe’s key role, may be one that Cooper tests).

But even if Cooper finds Joffe’s claims suspect, even if there were a coordinated effort to understand a now-proven effort by Russia to exploit various real relationships with people close to Trump and a now-proven effort to repeatedly hack Hillary, including in response to Trump’s request, it’s not clear that any of that matters to the single false statement charge against Sussmann.

From the very first, I observed that Durham obviously wanted to build a conspiracy charge against the Democrats, and that his case against Sussmann would be stronger if he did. That’s all still true (though evidence submitted thus far make me less convinced the conspiracy is what Durham thinks it is, and more convinced that if he were to charge it, we’d finally get the trial of Donald Trump for 2016 we deserve). But because Putin’s invasion of Ukraine led Durham to lose his trusty Alfa Bank partners in this effort, Durham is left trying to stick a bunch of procedurally square pegs in round holes, and doing so having missed deadlines to do it in proper fashion.

Durham may be legally entitled to get an interlocutory appeal on some of the decisions Cooper is likely to make in the next two weeks. That would delay the trial, something he has been trying to do from day one. But that would also require the assent of Lisa Monaco, and if his appeal was obviously abusive — as an appeal based off his own failure to follow the rules would be — he might not get that chance.

Even if you’re 100% sure there was a conspiracy here, even if you’re 100% sure Durham could find some unlikely hook on which to make that conspiracy criminal, that doesn’t mean he’ll be able to obtain — much less present — the evidence to make his case. Normally, prosecutors take that into account before charging people. Durham rather flamboyantly did not.

And for all the people who’ve spent three years falsely claiming that the Mueller Report showed no evidence that Trump conspired with Russia, you should think a lot more about how much more evidence of a conspiracy Mueller was able to show than Durham has, with an extra year to gather the evidence. Because all that evidence might become admissible if Durham continues to chase his own conspiracy theories.

Whether to immunize Rodney Joffe

As made clear above, some of these questions would be simplified if Joffe were called as a witness. Sussmann says that Joffe is a necessary witness to his defense, and Durham’s claims that he might still charge Joffe are just an abusive attempt to prevent Joffe from providing exculpatory testimony. Durham claims he hasn’t offered use immunity in a discriminatory way (he has given it to David Dagon and may give it to someone at Fusion), and claims that retaining Joffe as a subject of the investigation even after a five year statute of limitation on his actions has expired is not abusive. In a fairly ridiculous passage, Durham further claims that Joffe’s testimony would not be that helpful — but he ignores that Joffe would testify about his joint decision, with Sussmann, to help the FBI kill the NYT story.

Finally, the defendant fails to plausibly allege – nor could he – that the Government here has “deliberately denied immunity for the purpose of withholding exculpatory evidence and gaining a tactical advantage through such manipulation.” Ebbers, 458 F. 3d at 119 (internal citation and quotations omitted). The defendant’s motion proffers that Tech Executive-1 would offer exculpatory testimony regarding his attorney-client relationship with the defendant, including that Tech Executive-1 agreed that the defendant should convey the Russian Bank-1 allegations to help the government, not to “benefit” Tech Executive-1. But that testimony would – if true – arguably contradict and potentially incriminate the defendant based on his sworn testimony to Congress in December 2017, in which he expressly stated that he provided the allegations to the FBI on behalf of an un-named client (namely, Tech Executive-1). And in any event, even if the defendant and his client did not seek specifically to “benefit” Tech Executive-1 through his actions, that still would not render his statement to the FBI General Counsel true. Regardless of who benefited or might have benefited from the defendant’s meeting, the fact still remains that the defendant conducted that meeting on behalf of (i) Tech Executive-1 (who assembled the allegations and requested that the defendant disseminate them) and (ii) the Clinton Campaign (which the defendant billed for some or all of his work). The proffered testimony is therefore not exculpatory, and certainly not sufficiently exculpatory to render the Government’s decision not to seek immunity for Tech Executive-1 misconduct or an abuse.6 The defendant therefore has not met his burden of demonstrating, among other things, that the evidence provided by an immunized witness would tend to show he is “not guilty.” Ebbers, 458 F.3d at 119.

6 The defendant’s further proffer that Tech Executive-1 would testify that (i) the defendant contacted Tech Executive-1 about sharing the name of a newspaper with the FBI General Counsel, (ii) Tech Executive-1 and his associates believed in good faith the Russian Bank-1 allegations, and (iii) Tech Executive-1 was not acting at the direction of the Clinton Campaign, are far from exculpatory. Indeed, even assuming that all of those things were true, the defendant still would have materially misled the FBI in stating that he was not acting on behalf of any client when, in fact, he was acting at Tech Executive-1’s direction and billing the Clinton Campaign.

Thus far, Cooper has not done the one thing I would imagine he’d do if he’s considering this seriously — to order Durham to provide an ex parte description of what Durham really thinks Joffe is still at risk for.

But even on its face, Durham’s claim that Joffe would not be helpful is particularly problematic given that many of Durham’s evidentiary difficulties would be made easier if Joffe could be called to testify (for example, about documents he was party to but Sussmann was not).

If Cooper were to decide to make Durham choose to immunize Joffe or drop the prosecution — a decision that would not come before next Friday — all the other decisions would fall into place much more easily.

Update: Added Joffe immunity discussion.

Update: No fireworks at the hearing on a tech expert. Andrew DeFilippis did repeatedly misstate the FBI conclusion and did repeatedly backtrack on DOJ’s claim they don’t want to make the veracity of the claimed tie between Trump and Alfa an issue. He also admitted there’s no evidence in the email headers and billing records to prove his case, which is why he wants to talk about the creation of the data. Sean Berkowitz called the third white paper, created by Fusion, the equivalent of a WikiPedia page. There was also a reference to a meeting between Marc Elias and Joffe where the former allegedly talked about pushing the Trump-Russian line.

The most interesting details is that Durham has withdrawn the CIA guy who concluded the data was human created from their witness list; that’s also a conclusion he says the FBI doesn’t necessarily share. In any case, the conclusion sounds like it is about the same complaints others had about missing columns in the CSV tables.

Update, 4/25: Judge Cooper has issued an initial ruling on Durham’s expert witness. It limits what Durham presents to the FBI investigation (excluding much of the CIA investigation he has recently been floating), and does not permit the expert to address whether the data actually did represent communications between Trump and Alfa Bank unless Sussmann either affirmatively claims it did or unless Durham introduced proof that Sussmann knew the data was dodgy.

Finally, the Court takes a moment to explain what could open the door to further evidence about the accuracy of the data Mr. Sussmann provided to the FBI. As the defense concedes, such evidence might be relevant if the government could separately establish “what Mr. Sussmann knew” about the data’s accuracy. Data Mot. at 3. If Sussmann knew the data was suspect, evidence about faults in the data could possibly speak to “his state of mind” at the time of his meeting with Mr. Baker, id., including his motive to conceal the origins of the data. By contrast, Sussmann would not open the door to further evidence about the accuracy of the data simply by seeking to establish that he reasonably believed the data were accurate and relied on his associates’ representations that they were. Such a defense theory could allow the government to introduce evidence tending to show that his belief was not reasonable—for instance, facially obvious shortcomings in the data, or information received by Sussmann indicating relevant deficiencies.

Ultimately, Cooper is treating this (as appropriate given the precedents in DC) as a question of Sussmann’s state of mind.

Importantly, this is what Cooper says about Durham blowing his deadline (which in this case was a deadline of comity, not trial schedule): he’s going to let it slide, in part because Sussmann does not object to the narrowed scope of what the expert will present.

Mr. Sussmann also urges the Court to exclude the expert testimony on the ground that the government’s notice was untimely and insufficiently specific. See Expert Mot. at 6–10; Fed. R. Crim. P. 16(a)(1)(G). Because the Court will limit Special Agent Martin’s testimony largely to general explanations of the type of technical data that has always been part of the core of this case—much of which Mr. Sussmann does not object to—any allegedly insufficient or belated notice did not prejudice him. See United States v. Mohammed, No. 06-cr-357, 2008 WL 5552330, at *3 (D.D.C. May 6, 2008) (finding that disclosure nine days before trial did not prejudice defendant in part because its subject was “hardly a surprise”) (citing United States v. Martinez, 476 F.3d 961, 967 (D.C. Cir. 2007)).

This suggests Cooper may be less willing to let other deadlines slide, such as the all-important 404(b) one.

Deadlines for recent and coming days:

March 31: Status hearing at which Cooper catches Durham trying to do a motion to compel as a motion in limine

April 4: Sussmann submits MIL to exclude privileged documents, MIL to exclude hearsay FBI records, and Durham’s theories of conspiracy; Sussmann moves to immunize Rodney Joffe or dismiss the case; Durham omnibus MIL to do everything Sussmann objects to, plus include 404(b) broadly defined

April 6: Government moves to compel privileged documents

April 8: Sussmann moves to exclude government expert

April 11: Judge Christopher Cooper sets April 27 hearing for motions (making it clear he won’t dismiss case)

April 13: Cooper denies Sussmann’s motion to dismiss case

April 14: Sealed CIPA 6 hearing (for Durham to argue for substitutions)

April 15: Exchange of case-in-chief exhibits and exhibit lists by both parties

April 15: Production of trial witness list by the Special Counsel to the Defendant

April 15: Sussmann submits omnibus MIL response and opposition to government expert; Durham submits omnibus MIL response and defense of expert witness

April 18: Sussmann response to Durham’s bid to compel privileged documents

April 19: Motions to intervene by privilege holders: Hillary for America, Rodney Joffe, Perkins Coie, Fusion; subpoena to Hillary and DNC witnesses

April 20: At request of Sussmann, Cooper schedules hearing to address how much of Durham’s treatment of validity of claims (expert witness and accuracy of data); Cooper reiterates April 27 hearing for other topics

April 25: Government reply on motion to compel due

April 27: Motions hearing — specific topics TBD

April 29: Production of trial witness list by the Defendant to the Special Counsel

May 4: Hearing on privilege issues

May 5: Objections to case-in-chief exhibits due

May 9: Proposed jury instructions and verdict form due

May 9: Pre-trial conference and CIPA Section 6 hearing (if necessary)

May 10: Placeholder for further hearing (if necessary)

May 11: Administration of jury questionnaire

May 16: Jury selection