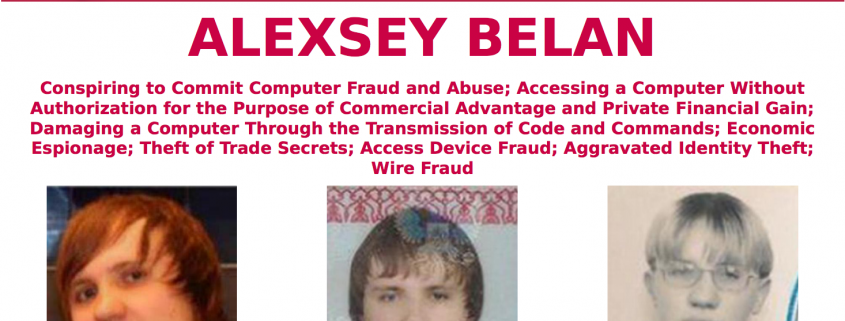

With much fanfare today, DOJ indicted four men for pawning Yahoo from 2014 to 2016. The indictment names two FSB officers, Dmitry Dokuchaev (who was charged by Russia with treason in December) and Igor Sushchin (who worked undercover at a Russian financial company), and two other hackers, Alexsey Belan (who has been indicted in the US twice and was named in December’s DNC hack sanctions) and Karim Baratov (who, because he lives in Canada, was arrested and presumably will be extradited).

Among the charged crimes, they accused Belan of using his access to the Yahoo network to game search results for erectile dysfunction drugs, for which he got commission from the recipient of the redirected traffic.

BELAN leveraged his access to Yahoo’s network to enrich himself: (a) through an online marketing scheme, by manipulating Yahoo search results for erectile dysfunction drugs; (b) by searching Yahoo user email accounts for credit card and gift card account numbers and other information that could be monetized; and (c) by gaining unauthorized access to the accounts of more than 30 million Yahoo users, the contacts of whom were then stolen as part of a spam marketing scheme.

But almost the entirety of the rest of the indictment — forty-seven charges worth — consist of stuff the FBI and NSA do both lawfully in this country and under EO 12333 in other countries (almost certainly including Russia).

Collect metadata and then collect content over time

Consider the details the indictment provides about how these Russians obtained information from Yahoo and other email services, including Google.

First, they collected a whole bunch of metadata.

[T]he conspirators stole non-content information regarding more than 500 million Yahoo user accounts as a result of their malicious intrusion.

The US did this in bulk under the PRTT Internet dragnet program from 2004 to 2011, and now conducts similar metadata collection overseas (as well as — in more targeted fashion — under PRISM). Mind you, the Russians got far more types of metadata than the US did under the PRTT program.

account users’ names; recovery email accounts and phone numbers, which users provide to webmail providers, such as Yahoo, as alternative means of communication with the provider; password challenge questions and answers; and certain cryptographic security information associated with the account, i.e. the account’s “nonce”

But this likely gives you an understanding of the kinds of things the US does collect overseas, as well as via the PRISM program.

The Russians then either accessed the accounts directly or created fake cookies to access accounts (note, the US also gets cookies lawfully from at least some Internet providers; I suspect they also do so under the new USA Freedom collection).

The indictment provides this comment about how many Yahoo user accounts the Russians accessed by minting cookies over the almost three years they were in Yahoo’s networks (January 2014 to December 1, 2016; this may not represent the entirety of the Yahoo content they accessed).

The conspirators utilized cookie minting to access the contents of more than 6,500 Yahoo user accounts.

Compare that to US requests from Yahoo in just 2015. Yahoo turned over content on at least 40,000 accounts under FISA (first half, second half) and content in response to 2,356 US law enforcement requests during a period when government requests averaged 1.8 account per request (so roughly 4,240 accounts).

Once they accessed the accounts, they maintained access to them, as the government does under PRISM.

The conspirators used their access to the AMT to (among other unauthorized actions) maintain persistent unauthorized access to some of the compromised accounts.

The Russians used both the metadata and content stolen from Yahoo to obtain access to other accounts, both in the US and in Russia.

the conspirators used the stolen Yahoo data to compromise related user accounts at Yahoo, Google, and other webmail providers, including the Russian Webmail Provider

Again, this is a key function of metadata requests by the US — to put together a mosaic of all the online accounts of a given target, so they can access all the accounts that may be of interest.

Like PRISM (but reportedly unlike the scan of all Yahoo emails FBI had done in 2015), the Russians were not able to search all of Yahoo’s email for content. Instead they searched metadata to find content of interest.

The AMT did not permit text searches of underlying data. It permitted the conspirators to access information about particular Yahoo user accounts. However, by combining their control of the stolen UDE copy and access to the AMT, the conspirators could, for example, search the UDE contents to identify Yahoo user accounts for which the user had provided a recovery email account hosted by a specific company of interest to the conspirators (e.g., “[email protected]”) showing that the user was likely an employee of the company of interest-and then use information from the AMT to gain unauthorized access to the identified accounts using the means described in paragraph 26.

And, as we’ll see below, the Russians “hunted SysAdmins,” as we know NSA does, to get further access to whatever networks they managed.

In other words, aside from the Viagra ads and credit card theft, the Russians were doing stuff that America’s own spies do all the time, using many of the same methods.

Let me be clear: I’m not saying this means America is just as evil as Russia. Indeed, as the list of targets suggests, a lot of this collection serves for internal spying purposes, something the US primarily does under the guise of Insider Threat analysis. Rather, I’m simply observing that except for some of the alleged actions of Belan, this indictment is an indictment for spying, not typical hacking.

The US didn’t indict anyone in China when it hacked Google in 2013. Nor did China indict the US when details of America’s far greater sabotage of Huawei networks emerged under the Snowden leaks. But the US chose to indict not just Belan, but also three people engaged in nation-state spying. Why?

Redefine economic espionage

I find all this particularly interesting given that the government included four charges — counts 2 and 4 through 6 — related to economic espionage for stealing the following:

a. Yahoo’s UDB and the data therein, including user data such as the names of Yahoo users, identified recovery email accounts and password challenge answers, and Yahoo-created and controlled data regarding its users’ accounts;

b. Yahoo’s AMT, its method and manner of functioning and capabilities, and the data it contained and provided; and

c. Yahoo’s cookie minting source code.

The US always justifies its global spying by claiming that it does not engage in industrial espionage, based on the flimsy explanation that it doesn’t share any information with allegedly private companies (including government contractors like Lockheed) they can use to compete unfairly.

But here we are, treating nation-state information collection — the kinds of actions our own hackers do all the time — as economic espionage. The only distinction here is that Belan also used his Yahoo access for personal profit. And yet Sushchin and Dokuchaev are also named in those counts.

Which raises the question of why DOJ decided to indict this as they did, especially since it risks an escalation of spying-related indictments. If I were Russia (maybe even China) I’d draw up indictments of American spies who’ve accessed Vkontakte or Yandex and accuse them of economic espionage.

I’ve got several suggestions:

- To leverage Baratov to learn more about the other three indictees (and FSB Officer 3, who is also mentioned prominently in the indictment)

- To expose Russia’s targets

- To expose FSB’s internal spying

Leverage Baratov to learn more about the other three indictees (and FSB Officer 3)

The US is almost certainly never going to get custody of Sushchin, Dokuchaev, or Belan, who are all in Russia safe from any extradition requests. That’s not true of Baratov, who was arrested and whose beloved Aston Martin and Mercedes Benz will be seized. These charges are larded on in such a way as to incent cooperation from Baratov.

Which means the government probably hopes to use the indictment to learn more about the other three indictees.

Remember: Belan was named in the sanctions on the DNC hack. So it may be that DOJ wants more information about those he works with, possibly up to and including on the DNC hack.

Expose Russia’s targets

Then there are the very long descriptions of the kind of people the accused collected on. The indictment highlights these three examples.

For example, SUSHCHIN, DOKUCHAEV, and BARATOV sought access to the Google, Inc. (“Google”) webmail accounts of:

a. an assistant to the Deputy Chairman of the Russian Federation;

b. an officer of the Russian Ministry of Internal Affairs;

c. a physical training expert working in the Ministry of Sports of a Russian republic;

Then provides this list of people hacked at Yahoo:

- a diplomat from a country bordering Russia who was posted in a European country

- the former Minister of Economic Development of a country bordering Russia (“Victim A”) and his wife (“Victim B”)

- a Russian journalist and investigative reporter who worked for Kommersant Daily

- a public affairs consultant and researcher who analyzed Russia’s bid for World Trade Organization membership

- three different officers of U.S. Cloud Computing Company 1

- an account of a Russian Deputy Consul General

- a senior officer at a Russian webmail and internet-related services provider

And this list of people targeted by Belan (who may or may not have been related to his own efforts rather than FSB’s):

- 14 employees of a Swiss bitcoin wallet and banking firm

- a sales manager at a major U.S. financial company

- a Nevada gaming official

- a senior officer of a major U.S. airline

- a Shanghai-based managing director of a U.S. private equity firm

- the Chief Technology Officer of a French transportation company

- multiple Yahoo users affiliated with the Russian Financial Firm

And this list of people Baratov hacked at Gmail and other ISPs:

- an assistant to the Deputy Chairman of the Russian Federation

- a managing director, a former sales officer, and a researcher, all of whom worked for a major Russian cyber security firm;

- an officer of the Russian Ministry of Internal Affairs assigned to that Ministry’s “Department K,” its “Bureau of Special Technical Projects,” which investigates cyber, high technology, and child pornography crimes;

- a physical training expert working in the Ministry of Sports of a Russian republic;

- a Russian official who was both Chairman of a Russian Federation Council committee and a senior official at a major Russian transport corporation

- the CEO of a metals industry holding company in a country bordering Russia

- a prominent banker and university trustee in a country bordering Russia

- a managing director of a finance and banking company in a country bordering Russia

- a senior official in a country bordering Russia

For those who weren’t alerted by Yahoo or Google they’d been hacked, these descriptions provide enough detail (as well as partial email addresses for some targets) to figure it out from the indictment.

Expose FSB’s internal spying

As these descriptions make clear, some of these targets are potentially well-connected people in Russia: a Russian Deputy Consul General, someone from Department K, the office of the Deputy Chairman of the Russian Federation, the Chairman of a Russian Federation Council committee (who also happens to be a businessman). Perhaps those people were targeted for sound political reasons — perhaps counterintelligence or corruption, for example. Or perhaps FSB was just trying to gain leverage in the political games of Russia.

Remember: One of the guys — Dokuchaev — is already being prosecuted in Russia for treason. These details might give Russia more details to go after him.

Sushchin is a special example. As the indictment explains, he was working undercover at some Russian financial firm, but it’s unclear whether his firm knew he was FSB or not.

SUSHCHIN was embedded as a purported employee and Head of Information Security at the Russian Financial Firm, where he monitored the communications of Russian Financial Firm employees, although it is unknown to the grand jury whether the Russian Financial Firm knew of his FSB affiliation.

But it’s clear that Sushchin’s role here was largely to conduct some very focused spying on the firm that he worked for.

In one instance, in or around April 2015, SUSHCHIN ordered DOKUCHAEV to target a number ofindividuals, including a senior board member ofthe Russian Financial Firm, his wife, and his secretary; and a senior officer ofthe Russian Financial Firm (“Corporate Officer l “).

[snip]

[I]n or around April 2015, SUSHCHIN sent DOKUCHAEV a list of email accounts associated with Russian Financial Firm personnel and family members to target, including Google accounts. During these April 2015 communications, SUSHCHIN identified a Russian Financial Firm employee to DOKUCHAEV as the “main target.” Also during these April 2015 communications, SUSHCHIN forwarded to DOKUCHAEV an email sent by that “main target’s” wife to a number of other Russian Financial Firm employees. SUSHCHIN added the cover note “this may be of some use.”

Maybe that operation was known by his employers; maybe it wasn’t. Certainly, his cover has now been blown.

All of which is to say that — splashy as this indictment is — the unstated reasons behind it are probably far more interesting than the actual charges listed in it.