At a hearing on July 25, accused Vault 7 leaker Joshua Schulte’s lawyer, Sabrina Shroff, argued that it’s possible if the government provides some forensic evidence that the CIA maintains is too classified to share, this case might avoid trial, either by identifying alternate culprits or leading her to advise her client to plead.

Mr. Kamaraju says that I would be forced anyway to then make a Section 5 motion to show relevance, etc. Well, maybe not. Maybe if I got the forensics, I would be able to say, hey, I think the government is completely wrong, Mr. Schulte is completely innocent, and you should go back and relook at your charging decisions because of X, Y, and Z in the forensics.

On the flip side, I could look at the forensics and say to my client, you know, maybe this isn’t the strongest case. Maybe we shouldn’t be going to trial. Not all discovery is asked for or relevant because it is only going to be used at trial. We asked for discovery because it is proper Rule 16 information that the defendant should have that would tell him about the charges and help him make proper decisions in the most serious or the most benign of cases.

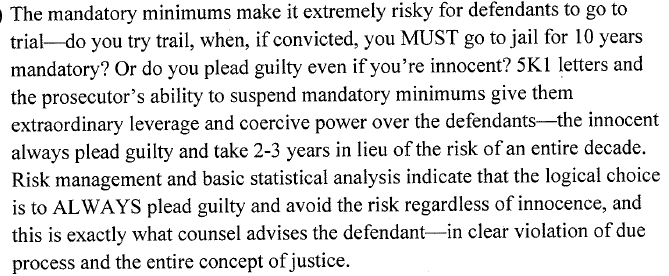

At issue, per an order Judge Paul Crotty issued days before the hearing (but which got released publicly afterwards) is evidence that would exist if a narrative Schulte seeded before he left the CIA were true. In addition to all the email he wrote at CIA (the government is giving him what he wrote, but not the responses), he wants “a complete forensic copy of the Schulte Workstation and DevLAN, so that his expert can conduct a comprehensive forensic analysis.” Ultimately, Crotty did not grant Schulte’s request, noting that he “has been accused of leaking information he obtained from his employment at CIA both before he was arrested and from his cell at MCC after his arrest.” Instead, he directed the defense to “submit[] a more tailored request [that] provides good reason for further forensic discovery in a motion to compel. In this context, it would also be helpful, for example, if Schulte would communicate his thinking of how others are responsible for the theft.”

Yet that didn’t work, at least not immediately. In the aftermath of that order, Schulte’s team said the Wall Counsel hasn’t responded substantively to a previously written request. That seems to be a justifiable complaint about the difficulties of working with Classified Information Protect Act and Wall Counsel (to say nothing of really complex technical issues which none of the lawyers fully understand). It’s like a giant game of telephone and Schulte’s right to a fair trial is at stake.

Which is why the government should take this offer from Shroff more seriously than they appear to have done: giving Schulte’s expert direct access to the full set of data he seeks.

We have offered to limit the access to either counsel or go even further and limit the access to just the expert. We have even offered that the CIA need not give it to us. We would go to the CIA or the expert would go to the CIA to review the forensics.

Even while it could use CIPA to limit what they give Schulte’s team, it would serve the government to give his expert this access.

I say that, first of all, because of who Schulte’s expert is: Columbia University CompSci professor Steve Bellovin. He’s not just some forensics guy with clearance. He’s someone who has served in governmental positions (most notably as PCLOB’s tech expert for a year). That means he has already seen government spying in action, and what he’d see here would be a server that got replaced, probably before April, and some hacking tools and targets there were in no way exceptional.

Just as importantly, Bellovin is well-respected in the activist community, both on technical matters and judgment. If Bellovin were to test Schulte’s alternative explanation for the leak of the Vault 7 files and Schulte subsequently pled (suggesting that Shroff had counseled that he not take his theories to trial), it would suggest that Schulte’s story didn’t hold up to Bellovin’s scrutiny.

If that happened, it would be a key statement about not just what Schulte has claimed, but about what WikiLeaks did, in releasing the files in 2017.

As the government tells it, Schulte got in a fight with a colleague in December 2015, which led him to sour on the CIA as early as February 2016. When the agency didn’t respond in the way he wanted to Schulte’s claim that the colleague had threatened him, he started to retaliate in April 2016 by first copying the backup server holding all the CIA’s hacking tools, then sending it to WikiLeaks. In short, the government’s story is that Schulte simply burned the CIA’s hacking capabilities to the ground because he felt like they wronged him, a fairly breathtaking claim for one of the most damaging leaks to the government in history.

Schulte’s story is harder to suss out for a number of reasons: the defense has avoided putting this in writing, in part in an attempt to protect their theory of defense, some of what Schulte has argued is classified and still sealed, and other parts consist of rants he has published online or in dockets, not coherent arguments. Plus, some of Schulte’s claims are clearly lies, most demonstrably his claim that, “Federal Terrrorists [sic] had no evidence of plaintiff actually using cell phone” before they got a warrant relying on an affidavit that included pictures of him using the phone he had in MCC.

Schulte’s story is harder to suss out for a number of reasons: the defense has avoided putting this in writing, in part in an attempt to protect their theory of defense, some of what Schulte has argued is classified and still sealed, and other parts consist of rants he has published online or in dockets, not coherent arguments. Plus, some of Schulte’s claims are clearly lies, most demonstrably his claim that, “Federal Terrrorists [sic] had no evidence of plaintiff actually using cell phone” before they got a warrant relying on an affidavit that included pictures of him using the phone he had in MCC.

Schulte’s theory, as available, consists of three parts:

- More people had access to the backup server from which the files were stolen than the government claims

- The files were relatively easier to steal from an offsite backup server than the onsite one the government alleges Schulte stole them from

- The likely culprits used security vulnerabilities he (claims to have) identified to CIA managers to steal the files

Evidence he’s making the first argument appears in his lawsuit against the Attorney General, where he claims the government has lied about the number of people who could access the server with the hacking tools.

AG lies about the number of people who had access to the classified information

Given a passage from the government’s response to his motion to suppress, Schulte must be referring to the claim that 200 people had access to the servers themselves, not the claim that 3-5 people had access to the backup server from which FBI claims the files were stolen. Schulte’s sealed filing appears to have argued that a second CIA group had access to the server.

Schulte does not dispute that the CIA Group was responsible for using and maintaining the LAN, that as of March 2016 fewer than 200 employees were assigned to the CIA Group, or that only these employees had access to the LAN. (See id. ,r 8(b)). Rather, Schulte argues that Agent Donaldson failed to note in the Covert Affidavit that a second CIA group (“CIA Group-2”), [redacted], allegedly also had access to the LAN.

For what it’s worth, the government disputes this claim outright. They introduce and conclude an otherwise redacted discussion by twice asserting this claim is false.

Schulte’s assertions about CIA Group-2’s access to the LAN are untrue [seven lines redacted] In short, Schulte is simply wrong.

Schulte’s claim that the files were more easily stolen from an offsite backup server may be more of a throwaway, based on what the government provided in discovery, reflecting what a contractor said almost a year into the investigation. (Remember that the government is not meaning to restate Schulte’s theories here, but instead to refute his claim that the initial affidavit against him included reckless errors.)

Schulte does not challenge that the Classified Information was taken from a back-up file, but instead argues that the back-up files were also stored at an offsite location (the “Offsite Server”), based on a network diagram of the LAN, and that, in one CIA Group contractor’s opinion, the “easiest” way to steal those back-up files was from the Offsite Server. None of this information, however, renders Agent Donaldson’s assessment misleading. Initially, while it is true that the back-up files were also stored in an Offsite Server, Agent Donaldson never suggested that the only place that the back-up files existed was the Back-up Server. Nor did Agent Donaldson opine in the abstract on the easiest method of exfiltrating the Classified Information from the LAN. Rather, he merely stated that it was “likely” that the Classified Information had come from the Back-Up Server, an eminently reasonable conclusion, given that the Back-Up Server contained the back-up files that mirrored the Classified Information, and Schulte–whom the FBI properly identified as a likely perpetrator of the theft–had access to it. Gates, 462 U.S. at 230-31 (courts do not isolate each factor of suspicion but look at the totality of the circumstances). The opinion of the contractor–who did not have access to all of the information and who had no relevant investigatory experience–in no way undermines that assessment, particularly when (i) that opinion is contradicted by [redacted], a LAN system administrator and a witness upon whom Schulte relies in his motion, who stated that “the easiest way to steal the data leaked by WikiLeaks” was for someone with administrative access to the LAN to “simply remov[e] the backup file from the network application” (i.e., the Back-Up Server) (Shroff C. Decl., Ex. I); and (ii) even if the contractor’s opinion was relevant, it was not conveyed to the FBI until February 2018, nearly a year after the date of the Covert Affidavit, see Garrison, 480 U.S. at 85.

Significantly, the government bases its claim that Schulte leaked classified information from jail in part on him sharing a “Network Structure Document” with someone (probably a reporter); given that some of the other information he is alleged to have leaked in violation of classification or protective orders was meant to sustain his claims of innocence, this probably does too. If so, that would suggest he was floating this theory about a year ago.

Finally, in his Presumption of Innocence blog, Schulte maintains that the CIA network was vulnerable in ways that he claims he raised with the CIA before he left.

I reported numerous security vulnerabilities that I discovered within our network and particularly issues with system administration, backup, and protection of some of our prominent tool sets. I was continually met with pushback and retaliatory responses that ultimately forced me to resign. My final acts were to file complaints with the OIG and the House Select Committee on Intelligence to hopefully prevent future retaliatory actions against others.

So while the government claims that Schulte retaliated by leaking the CIA’s hacking tools because the CIA wasn’t treating him with the respect he thought he deserved, Schulte appears to be claiming that possibly members of CIA’s Group-2 or perhaps even outsiders stole the files via vulnerabilities he identified before he left.

While not exactly the same, WikiLeaks made related claims when they released the files, in part as rationale for publishing them.

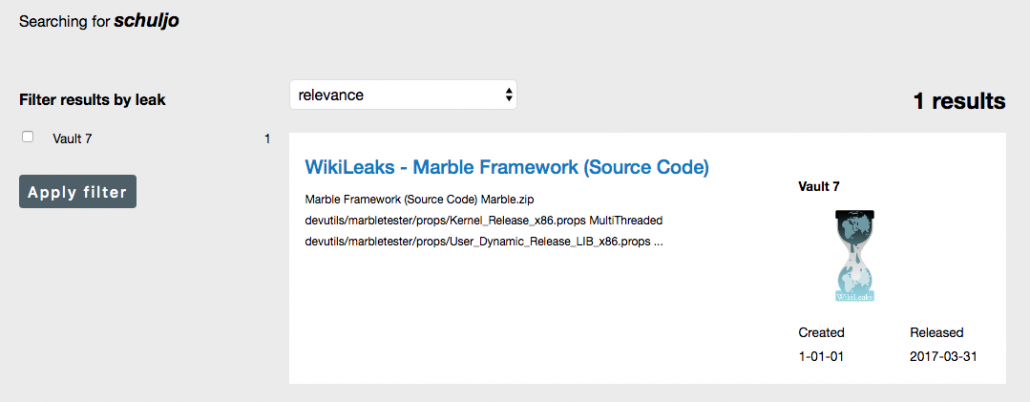

Compare what we can make out of Schulte’s defense with what WikiLeaks published in its “press release” accompanying the first Vault 7 release. WikiLeaks describes CIA “losing control” of its hacking tools, not someone leaking them.

Recently, the CIA lost control of the majority of its hacking arsenal including malware, viruses, trojans, weaponized “zero day” exploits, malware remote control systems and associated documentation. This extraordinary collection, which amounts to more than several hundred million lines of code, gives its possessor the entire hacking capacity of the CIA. The archive appears to have been circulated among former U.S. government hackers and contractors in an unauthorized manner, one of whom has provided WikiLeaks with portions of the archive.

While it mentions former US government hackers (which could include Schulte), it also invokes contractors (the press release elsewhere mentions Hal Martin), and contractors were the presumed source for Vault 7 files at the time. While WikiLeaks acknowledges that the files came from “an isolated, high-security network situated inside the CIA’s Center for Cyber Intelligence in Langley, Virgina [sic]” the description of the archive circulating in unauthorized fashion suggests that WikiLeaks is claiming the files were more broadly accessible.

The “press release” also suggests CIA’s hacking division had 5,000 users, implying all were involved in the production of hacking tools.

By the end of 2016, the CIA’s hacking division, which formally falls under the agency’s Center for Cyber Intelligence (CCI), had over 5000 registered users and had produced more than a thousand hacking systems, trojans, viruses, and other “weaponized” malware.

While that may or may not be the CIA Group-2 Schulte claims had access to the servers, it certainly suggests a far larger universe of potential sources for the stolen files than the 200 the government claims, much less the around 5 SysAdmins who had privileges to the backup server.

The purported motive for releasing these tools — both that of the source and of Assange — is partly the insecurity of having such tools lying around.

In a statement to WikiLeaks the source details policy questions that they say urgently need to be debated in public, including whether the CIA’s hacking capabilities exceed its mandated powers and the problem of public oversight of the agency. The source wishes to initiate a public debate about the security, creation, use, proliferation and democratic control of cyberweapons.

Once a single cyber ‘weapon’ is ‘loose’ it can spread around the world in seconds, to be used by rival states, cyber mafia and teenage hackers alike.

Julian Assange, WikiLeaks editor stated that “There is an extreme proliferation risk in the development of cyber ‘weapons’.

[snip]

Securing such ‘weapons’ is particularly difficult since the same people who develop and use them have the skills to exfiltrate copies without leaving traces — sometimes by using the very same ‘weapons’ against the organizations that contain them.

[snip]

Once a single cyber ‘weapon’ is ‘loose’ it can spread around the world in seconds, to be used by peer states, cyber mafia and teenage hackers alike.

In other words, WikiLeaks justified posting development notes for a significant portion of CIA’s hacking tools — and ultimately the source code for one — to prevent “teenage hackers” from obtaining such weapons and using them. (By this February, a security researcher had made his own hacking module based off what WikiLeaks had released.) A key part of that claim is the risk that CIA itself had not sufficiently secured its own tools, that they were “circulat[ing] … in an unauthorized manner.” That is, WikiLeaks purports to be the fulfillment of and remedy for precisely the risk Schulte claims — in his Presumption of Innocence blog — he warned the CIA about.

Except the government claims that’s not true.

It is true, as the affidavit in dispute in Schulte’s motion to suppress lays out, that Schulte wrote a “draft resignation letter” purporting to warn about these dangers and, on his last day, sent the CIA’s Inspector General a letter raising the same issues. The government reviews what he did at length in their response to his motion to suppress.

Agent Donaldson discussed the circumstances of Schulte’s resignation from the CIA in November 2016, including a letter and email he wrote complaining about his treatment. (Id. ,i,i 19-20). On October 12, 2016, Schulte sent an email to another CIA Group employee with the subject line “ROUGH DRAFT of Resignation Letter *EYES ONLY*,” which attached a three-page, single-spaced letter (the “Letter”). (Id. ,i 19(a)). In the Letter, Schulte stated that the CIA Group management had unfairly “veiled” CIA leadership from various of Schulte’s “concerns about the network security of the CIA Group’s LAN” and that “[t]hat ends now. From this moment forward you can no longer claim ignorance; you can no longer pretend that you were not involved.” (Id. ~ 19(a)(ii)). The Letter also stated that Schulte was resigning because management had “‘ignored'” issues he had raised about ‘”security concerns,”‘ including that the LAN was ‘”incredibly vulnerable’ to the theft of sensitive data.” (Id. ~ 19(a)(iii)). In particular, Schulte stated that the “inadequate CIA security measures had ‘left [the CIA Group’s LAN] open and easy for anyone to gain access and easily download [from the LAN] and upload [sensitive CIA Group computer code] in its entirety to the [public] internet.”‘ (Id.~ 19(a)(iv)).

[snip]

However, on November 10, 2016, Schulte’s last day at the CIA, Schulte sent an internal email to the CIA’s Office of Inspector General (“OIG”), which Schulte marked “Unclassified,” advising that he had been in contact with the U.S. House of Representatives’ Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence regarding his complaints about the CIA (the “OIG Email”). (Id ~ 19(c)). The OIG Email raised many of the same complaints in the Letter, including “the CIA’s treatment of him and its failure to address the ‘security concerns’ he had repeatedly raised in the past.” (Id ~ 19(c)(i)). Although Schulte had labeled the OIG Email “Unclassified,” the CIA determined that the OIG Email did in fact contain classified information. (Id.~ 19(c)(iii)). Schulte nevertheless printed and removed the email from the CIA when he left that day. (Id ~ 19( c )(ii)).

As the government response notes, the affidavit describes that Schulte never actually sent the resignation letter.

Agent Donaldson noted that Schulte did not appear to send the Letter. (Id. ~ 19(b)).

A later discussion of the resignation letter as part of a summary of the probable cause against Schulte goes still further, claiming that there is no record that Schulte raised security concerns with CIA management (which is presumably one reason he asked for all his emails).

(iv) drafted a purported “resignation email,” in which he claimed essentially that he had warned CIA management about security concerns with the LAN7 that were so significant that the LAN’s contents could be posted online–precisely what happened four months later (see id. ,r 19);

7 There is no record of Schulte reporting any such security concerns to CIA management.

The government makes Schulte’s allegedly false claim to have raised concerns about the security of the CIA tools a key part of its short summary of the probable cause against Schulte, insinuating that Schulte wrote both the resignation letter and the letter to the IG (which he wrote five and six months, respectively, after the government alleges he stole the files) as a way to create a cover story for the leaked documents.

Thus, even if the Covert Affidavit was rewritten to Schulte’s (incorrect) specifications, it would still establish probable cause by showing that Schulte was a CIA employee with a grudge against the CIA and a track record of improperly accessing and taking classified information, who left the CIA claiming that classified information from the LAN would one day be sprayed across the Internet and who worried about the investigation when his “prophecy” came to pass.

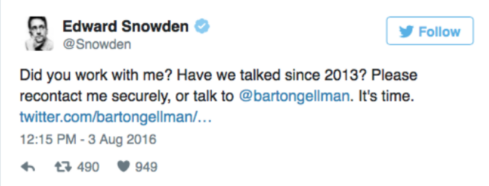

Of course, the government — especially intelligence agencies like the NSA and CIA — always dismiss the claims to be whistleblowers of leakers. The CIA claimed Jeffrey Sterling only leaked details of the Merlin operation because he was disgruntled about an EEOC complaint they had denied. NSA denied that Edward Snowden had raised concerns — first at CIA about its security, then at NSA about the boundaries of EO 12333 and Section 702. In the former case, however, the government knows of at least three other people who thought Sterling’s concerns had merit, and the actual details around Merlin’s own activities were a clusterfuck. In the latter, even a really problematic HPSCI report acknowledges that both incidents occurred, and NSA ultimately released enough of the backup to show that the NSA undersold the latter instance (though Snowden’s claims were not as substantive as he claimed).

Thus far, Schulte has presented no such counterevidence (indeed, the docket does not show his team submitted a reply to the government’s response before their August 16 deadline, though a reply could be held up in classification review). [Update: This letter asking to sever the MCC charges from the WikiLeaks charges says they’re still working on their replies.]

There may be a very good reason why Schulte’s defense didn’t go there: because one of the lies the government claims he told to FBI Agents on March 20 and 21, 2017 involves making CIA systems more vulnerable to the theft of data.

On or about March 20 and 21, 2017, Schulte … denied ever making CIA systems vulnerable to the theft of data.

Aside from this mention, this allegation doesn’t otherwise appear in public documents I’m aware of. But the implication is that before Schulte wrote two documents that — the government claims — served to establish a cover story claiming he leaked the documents because CIA’s server was vulnerable to theft, he tampered with the CIA’s server to make it more vulnerable to theft.

There actually is evidence that the server was vulnerable to theft. In Crotty’s opinion, he overruled the government’s effort to withhold some internal reports on the leak under CIPA. He explained,

These documents [redacted] might help Schulte advance a theory that DevLAN’s vulnerabilities could have allowed someone else to have taken the leaked data. They also support the defense’s theory that Schulte’s behavior while an employee of the CIA was consistent with someone who was trying to help the agency address security flaws, rather than someone who was a disgruntled employee.

That’s why it’d be worthwhile for Bellovin to have access to the server directly: to test not just how vulnerable the servers really were (I bet he’d be willing to help improve their security along the way!), but also to test himself whether there’s any evidence that someone besides Schulte exploited those vulnerabilities.

The government’s reliance on CIPA in this case is an attempt to try Schulte for an unbelievably sensitive leak without (as Crotty laid out) giving him opportunity to leak some more.

But the case goes beyond Schulte’s actions, to implicate WikiLeaks’ actions (court filings make it clear that WikiLeak’s claims around this leak were false in another manner, one which I’m not describing at the government’s request). And while details of CIA’s unexceptional hacking program are useful for researchers to have, it would matter if the stated rationale for releasing them was bullshit manufactured after the fact. That’s all the more true if WikiLeaks — which used to boast its perfect record on verification — knew the claim to be false, particularly given how and when it released these files, with an attempt to extort the US government and in the wake of the Russian hacks, at a time CIA would have needed these tools to prevent follow-ups.

Three months after Schulte’s trial (if this does go to trial), the government will be embroiled in attempting to extradite Julian Assange under charges that are rightly being attacked as an assault on the press. The government is never going to reveal all it knows about Assange (including, pertinent to this case, whether there’s any evidence Assange used some of the CIA’s own tools for his own benefit). Bellovin, if he were permitted to review the CIA server, would never be in a position to reveal what he learned; but his role in this case provides a rare opportunity for a trusted outsider to weigh in on a controversial case.

Effectively, a guy who authored CIA’s obfuscation tool and purportedly planned an information war from jail — complete with fake FBI and CIA personas — may have created the vulnerability he claimed to be exposing by leaking the files. If Bellovin were able to test that possibility, it would go a long way to shift an understanding about WikiLeaks recent intentions with the US government.