Update: Alexander’s office has conceded Udall and Wyden’s point about the classified inaccuracy. It also notes:

With respect to the second point raised in your 24 June 2013 letter, the fact sheet did not imply nor was it intended to imply “that the NSA has the ability to determine how many American communications it has collected under section 702, or that the law does not allow the NSA to deliberately search for the records of particular Americans.”

He then cites two letters from James Clapper’s office which I don’t believe have been published.

Joshua Foust tries to refute this post and in doing so proves once again he doesn’t understand the meaning of “target” under Section 702.

Out of courtesy to him, I’m going to rewrite this post to help him understand it. The issue is not whether the US can “target” a US person without a warrant. They can’t. The issue is what the US does with US person data they collect incidentally off a legal target (which must be a foreigner overseas collected for a legitimate intelligence purpose).

At issue is this sentence in the Mark Udall/Ron Wyden letter to Keith Alexander.

Separately, this same fact sheet states that under Section 702, “Any inadvertently acquired communication of or concerning a US person must be promptly destroyed if it is neither relevant to the authorized purpose nor evidence of a crime.” We believe that this statement is somewhat misleading, in that it implies that the NSA has the ability to determine how many American communications it has collected under section 702, or that the law does not allow the NSA to deliberately search for the records of particular Americans.

The passage says that the claim, “any inadvertently acquired communication of or concerning a US person must be promptly destroyed” is “somewhat misleading,” for two reasons:

- It implies that the NSA has the ability to determine how many American communications it has collected under section 702

- It implies that the law does not allow the NSA to deliberately search for the records of particular Americans

Now, before I get into bullet point 2, which is the one in question, note that this entire passage is talking about “inadvertently acquired communication of or concerning a US person.” This is not information on someone who has been targeted. It discusses what happens to information collected along with the communications of those who’ve been targeted (say, by emailing the target). Therefore, this entire passage is irrelevant to the issue of what happens with the targeted person’s communication. The Udall/Wyden claim is not about targeting in the least; it is about incidental collection.

Okay, bullet point 2: Udall and Wyden claim that Alexander’s fact sheet is misleading because it implies the law does not allow the NSA to deliberately search for the records of particular Americans. They could be wrong, but their claim is that it is misleading for Alexander to suggest that the law does not allow the NSA to deliberately search for the records of particular Americans. That means they believe the law does allow the NSA to deliberately search for the records of particular Americans, otherwise they wouldn’t think his statement was misleading.

Now, if it were just Udall and Wyden making this claim, it’d be a he-said/he-said. But pointed out that this claim is not new at all. It’s not even one limited to Udall and Wyden. In the FAA report released by Dianne Feinstein last year, it said,

Finally, on a related matter, the Committee considered whether querying information collected under Section 702 to find communications of a particular United States person should be prohibited or more robustly constrained. As already noted, the Intelligence Community is strictly prohibited from using Section 702 to target a U.S. person, which must at all times be carried out pursuant to an individualized court order based upon probable cause. With respect to analyzing the information lawfully collected under Section 702, however, the Intelligence Community provided several examples in which it might have a legitimate foreign intelligence need to conduct queries in order to analyze data already in its possession.

First, the report describes a debate the committee had:

The Committee considered whether querying information collected under Section 702 to find communications of a particular United States person should be prohibited or more robustly constrained.

The committee debated two things:

- Whether querying information collected under Section 702 to find communications of a particular United States person should be prohibited.

- Whether querying information collected under Section 702 to find communications of a particular United States person should be more robustly constrained.

Bullet point 1 makes it clear they were debating whether they should prohibit this activity. If they had to consider that, it means that it is not prohibited (which is precisely what Udall and Wyden say–that the law allows it). Bullet point 2 says they also considered whether they should “more robustly constrain” it, which suggests (though does not prove) that it is going on now, otherwise there’d be nothing to constrain.

The IC IGs won’t tell us how much of this goes on–they claim they have no way of counting it, which ought to alarm you, because it says they’re not actually tracking it via some kind of auditing function.

I defer to his conclusion that obtaining such an estimate was beyond the capacity of his office and dedicating sufficient additional resources would likely impede the NSA’s mission. He further stated that his office and NSA leadership agreed that an IG review of the sort suggested would itself violate the privacy of U.S. persons.

Now, as I already laid out, what we’re talking about is not targeting a US person–focusing collection on that person. What we’re talking about is what you can do with the US person data collected “incidentally” with the communications collected of that targeted person. That information–as the minimization guidelines describe–is lawfully collected. The big question is what you can do with it once you have collected it, and in many but not all cases there are restrictions against circulating that information before you’ve hidden the identity of the US person in question.

The last part of the passage from the SSCI says,

With respect to analyzing the information lawfully collected under Section 702, however, the Intelligence Community provided several examples in which it might have a legitimate foreign intelligence need to conduct queries in order to analyze data already in its possession.

Again, some amount of US person data is collected under Section 702 along with the data of the targeted person (if it weren’t, they wouldn’t need minimization procedures). It is lawfully collected. The question is what you’re allowed to do with it. And as part of the debate the committee had about whether they were going to “prohibit” or “more robustly constrain” the querying of US person data that was lawfully collected as incidental data, SSCI describes the Intelligence Community (which includes, in part, the NSA, the CIA, and the FBI) providing several reasons why it might need to conduct queries of this data. And the committee agreed that these reasons were “legitimate foreign intelligence needs.”

The minimization procedures from 2009, at least, require destruction of US person data if it is “clearly not relevant to the authorized purpose of the acquisition (e.g., the communication does not contain foreign intelligence information).” (3(b)(1)) What is not immediately destroyed may be kept for up to 5 years. But it only destroys the stuff that is “clearly not relevant,” not data that might be relevant to the purpose of the investigation.

Now, while the language is not exact, the SSCI report’s description of data that has a “legitimate foreign intelligence” surely includes “foreign intelligence information.” This is kind of backwards (which may be part of complaint from Udall and Wyden), but unless the information is clearly not relevant — and the intelligence community says some of this data has legitimate intelligence purposes — then it is retained. This is probably why Udall and Wyden think Alexander’s “must be promptly destroyed” is misleading, because if the IC thinks they might need to query it because it would serve a legitimate foreign intelligence purpose, then it is not.

So who makes this decision whether to keep the data? “NSA analyst(s) will determine whether it … is reasonably believed to contain foreign intelligence information.” (3(b)(4)) The NSA, not FBI or CIA.

And this data cannot just be retained. It can also be “forwarded to analytic personnel responsible for producing intelligence information from the collected data.” (3(b)(2))

Now, in most cases, that information must be anonymized (which is what Kurt Eichenwald discusses here, which Foust cites). But it has always been the case there are exceptions to that rule. Some exceptions are if:

- The Director of NSA specifically determines, in writing, that the communication is reasonably believed to contain significant foreign intelligence information. (5(1)) In that case the information goes to the FBI. [Update: This distribution is permitted with domestic communication–that is, US to US person.]

- A recipient requiring the identity of such person for the performance of official duties needs the identity of the United States person to understand foreign intelligence information or assess its importance. (6(b)(2) This sometimes, but not always, happens after an initial distribution.

There are actually a slew more exceptions but these two should suffice. Again, these rules on distribution (except as they affect technical data base information, which might be relevant here, but not necessary) are not new with FAA. They’ve long been in place.

Again, this is all about what happens to incidentally collected data, not the data of the person actually targeted. Which is why these two passages are irrelevant to the entire point (the second of which Foust thought I was leaving out because it hurt my point).

As already noted, the Intelligence Community is strictly prohibited from using Section 702 to target a U.S. person, which must at all times be carried out pursuant to an individualized court order based upon probable cause.

[snip]

The Department of Justice and Intelligence Community reaffirmed that any queries made of Section 702 data will be conducted in strict compliance with applicable guidelines and procedures and do not provide a means to circumvent the general requirement to obtain a court order before targeting a U.S. person under FISA.

What they say is that the government is prohibited from targeting a US person without a warrant and that any other things done with incidentally collected data must be conducted in strict compliance with applicable guidelines, which are the minimization procedures I just reviewed (though again, those are from 2009 so they may have changed somewhat). The passage very clearly envisions making queries of the data and very clearly considers such queries to be distinct from the targeting of a US person.

And the minimization procedures make it clear that if data is not “clearly not foreign intelligence,” (that is, if it might be foreign intelligence, as this queried data is, according to the IC) then it is retained, at least through the initial (NSA-conducted) review. Where it can be queried, so long as the other minimization procedures are met.

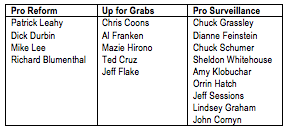

One final thing. Foust is actually wrong when he suggests the IC asked for new authority (in any case, the only conclusion would be that they got it). Rather, in both the SSCI and the Senate Judiciary Committee, Senators tried to limit this authority. In SJC, Mike Lee, Dick Durbin, and Chris Coons submitted an amendment to (among other things) prohibit,

the searching of the contents of communications acquired under this section [702] in an effort to find communications of a particular United States person…

…Except with an emergency authorization.

Dianne Feinstein fought the amendment by arguing such a prohibition would have made it harder to find Nidal Hasan (whom we didn’t find anyway, and whose communications with Anwar al-Awlaki may well have been traditional FISA collection). But at one level that makes sense.

Sheldon Whitehouse said that such a restriction would “kill this program.”

I may not like what Whitehouse stated. But I do trust his judgement about how central to this program is access to US person communications.

That doesn’t say how much of this stuff goes on (though it does seem to suggest it does). But it does say we ought to at least track it.