Thursday: Bad Girls

One thing before I go any further…look just above these words, below this post’s title and to the right of the date of publication. See the name ‘Rayne’? That’s me, that’s my byline. Please note there are multiple contributors here at emptywheel. The entire site is eponymously named for its owner, Marcy Wheeler, whose online name and byline is the same as this blog. Check the byline on our posts if you haven’t done so in the past. You’ll note we have different voices and opinions, different writing styles. I tend to be the most open about my dislike for what the Republican Party has become since 1978, when I last toyed with being Republican. Marcy and the rest of the crew tend to be more generous or less open in their vituperation. Take note of the byline when when you read and comment, thanks.

Still indulging in female artist K-pop, choosing this video for a very specific reason…

TWO DAYS

That’s it, what’s left of today and all day tomorrow — that’s all the U.S. House will be in session for July. Outstanding job this week trashing the EPA with bullshit riders, GOP members. Way to fucking go with extending your run serving corporations ahead of the people.

Tick-tock.

BAD GIRL (UK edition)

After today’s wash list of badness, I can hardly wait to hear what comes of May’s visit on Friday to Scotland.

- New UK PM Theresa May doubles down on the stupid naming Priti Patel to Dept of International Development (The Independent) — In spite (or because) of Priti Patel’s 2013 opinion that the DofID should be eliminated and focus aimed solely on trade. Patel’s been referred to as a “Tory ‘robot’.”

- David Davis, named ‘Brexit Czar’, already beating drums for trade negotiations now () — taking an offensive stance on Article 50, wanting deals BEFORE executing the article, in essence extending the two-year period for negotiations. That’s not what the Lisbon Treaty specifies, though. And European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker has already warned the UK the EU won’t negotiate at all before Article 50 has been filed.

- May abolished the Department for Energy and Climate Change, absorbing it into the new Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy (The Independent) — Wow. Pure climate denialism combined with fascism. Stunning level of stupidity.

- Anna Leadsom, new Environment Secretary, advocates burning everything down (The Independent) — Not really, but bloody close to that given her support for fox hunting, selling national forests, and climate change denialism.

BAD GIRL (domestic edition)

- Michigan Gov. Snyder appoints former BP external affairs pro to Environmental Quality (Detroit Free Press) — In a move mimicking UK PM Theresa May’s oppositional defiance and idiocy on the environment and climate change, Snyder does the exact opposite of what’s needed to save the environment and picks someone with background in environmental damage. Keep in mind there’s an ongoing conflict about an ruptured Enbridge Energy oil pipeline* running beneath the Mackinaw Straits between two of the largest bodies of fresh water in the world. [* not ruptured but at risk of rupture, and very little accountability on its operation in spite of its age and sensitivity of the water and land it travels. Enbridge is responsible for the largest inland oil leak in the U.S., near Kalamazoo MI.]

PokéGone

The list of accidents resulting from distraction by Pokémon GO grows by leaps and bounds. These are among the worst so far. Just a matter of time before a fatality occurs.

- Two guys fall over a 90-foot oceanfront bluff chasing Pokémon characters (LAT) — How do you miss a cliff that high, let alone the roar of the ocean below?

- Guy glances at his phone to check for Pokémon, wraps his car around a tree (Consumerist) — Wakes up in hospital, lucky to be alive. Just look at the car.

- Guy falls into Prospect Park pond while chasing a Pokémon (Cosmopolitan) — Hey, do you see a pattern here, besides Pokémon?

Wheels

- California regulator nixes Volkswagen’s 3.0L passenger diesel fix (Ars Technica) — No surprise to me whatsoever. I’ve said repeatedly there’s no clean diesel technology. Still isn’t. Just buy the cars back and tell consumers to buy a hybrid instead if they want clean passenger transportation.

- Consumers Reports tells Tesla to eliminate “Autopilot” label on self-driving technology (Phys.org) — Too confusing to so-called drivers in spite of warnings they should pay attention to driving at all times.

- New bug bounty offered by Fiat Chrysler (Naked Security) — First of its kind offered by any Detroit automakers, the bounty comes after Chrysler vehicles featuring the wireless UConnect entertainment system were hacked by white hats last year.

Keep an eye on this topic

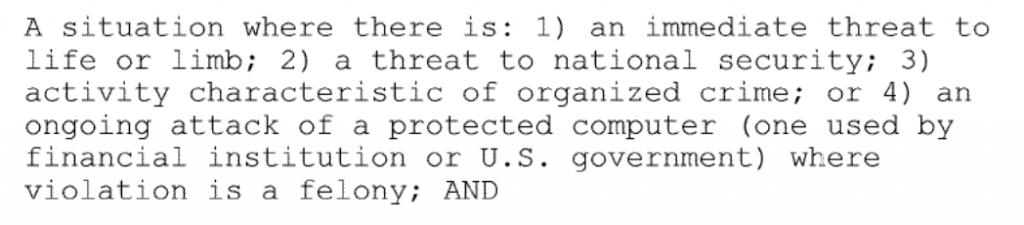

- U.S. SDNY’s Judge William Pauley ruled evidence collected by DEA using Stingrays is inadmissible (New York Law Journal) — Pauley wrote,

Absent a search warrant, the Government may not turn a citizen’s cell phone into a tracking device. Perhaps recognizing this, the Department of Justice changed its internal policies, and now requires government agents to obtain a warrant before utilizing a cellsite simulator.

I’m sure there will be more on this case in the near future.

Catch you tomorrow for the last in-session day in U.S. House.