What Is DOJ Really After in Raiding Hannah Natanson?

I shuddered when I read this article from Hannah Natanson in real time, in December, which was the first I really took notice of the name behind a flood of important reporting on Trump’s attack on the government. A chronicle of the hell Trump had subjected government workers to, it was a great article.

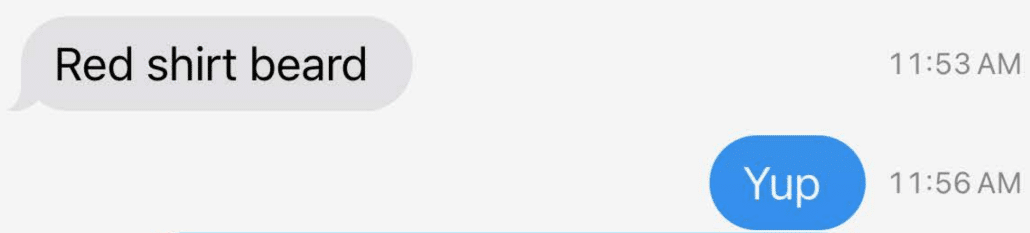

Signal message sent Feb. 23

I think about jumping off a bridge a couple times a day.Signal message sent March 21

I want to die. It’s never been like this.Signal message sent May 21

I have been looking at how much I am worth alive, as opposed to dead.

But in telling that story, Natanson told how she protected the anonymity of her sources.

Colleagues told me to join our internal tip-sharing Slack channel #federal-workers, then talk to Washington economics editor Mike Madden, who was coordinating our DOGE coverage. I started copying and pasting tips there as fast as I could, scraping out identifying details. Then, phone buzzing every few seconds, I speed-walked around the building until I found Mike. Skipping with grace over the fact we’d never met (and I didn’t work for him), he ferried me to every corner of the seventh floor: Meet the team covering technology. The team covering national security. The White House editors. Eventually, The Washington Post created a beat for me covering Trump’s transformation of government, and fielding Signal tips became nearly my whole working life.

[snip]

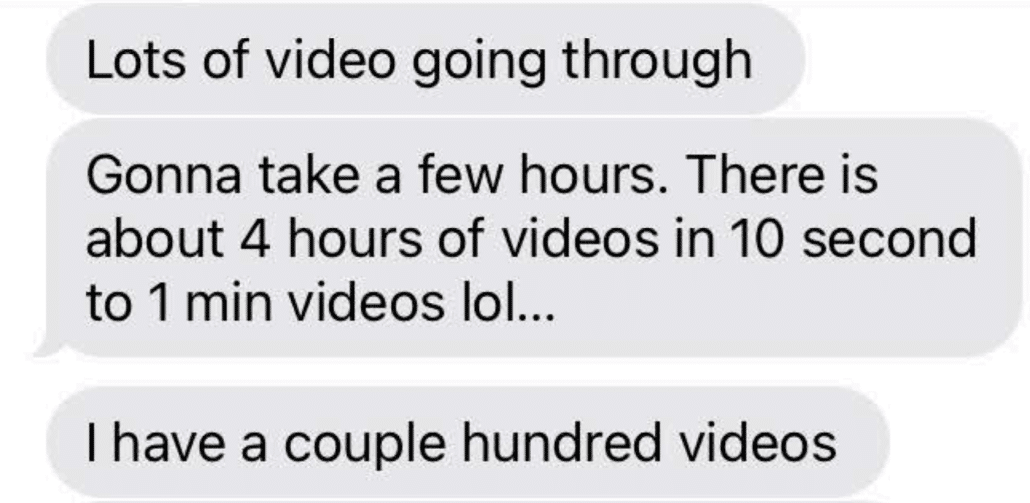

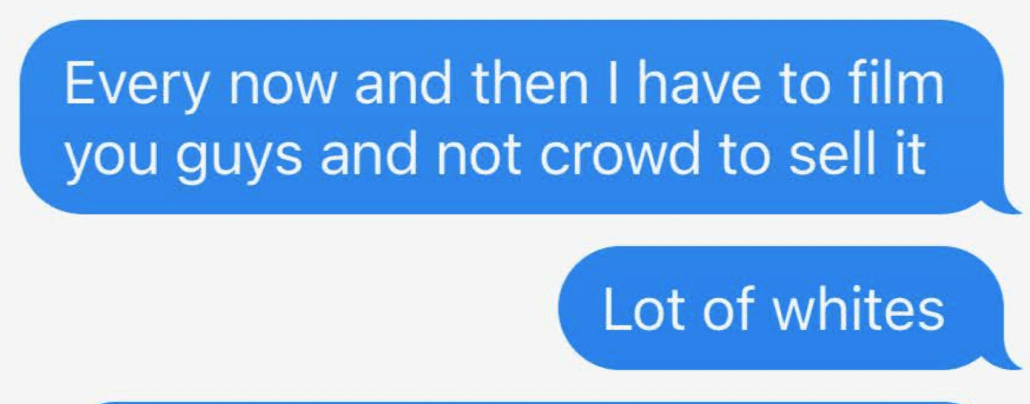

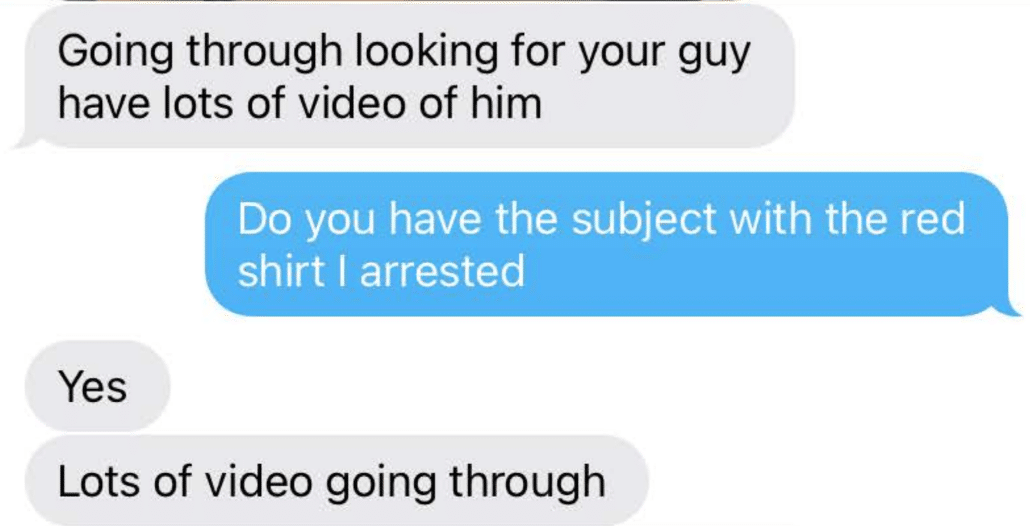

After consulting Post lawyers, I developed what we felt was the safest possible sourcing system. If I planned to use someone in a story, I asked them to send me a picture of their government ID, then tried to forget it. I kept notes from reporting conversations in an encrypted drive, never writing down anyone’s name. To Google-check facts and identities, I used a private browser with no search history. I retitled every Signal chat by agency — “Transportation Employee,” “FDA Reviewer,” “EPA Scientist” — until the app, unable to keep up, stopped accepting new nicknames. (Then I started moving contacts into two-person group chats, which I could still rename.)

Three weeks later, FBI seized the phone on which all those contacts were labeled with aliases. When they searched her home, she was logged into the Slack on which she had shared all those leads with colleagues. They seized the encrypted drive on which she had her notes.

In short, she publicly revealed where to look for everything else, and three weeks later, Trump agents came and took it all.

(For the record, this is not the only time I’ve shuddered about publicly disclosed operational security lately; far too many profiles on anti-ICE activism describe how their Signal trees are structured and what tools the central dispatcher uses to keep everything flowing.)

And that’s one of many reasons the unusual openness of the indictment against Aurelio Perez-Lugones — the pretext FBI used for raiding Natanson — terrifies me.

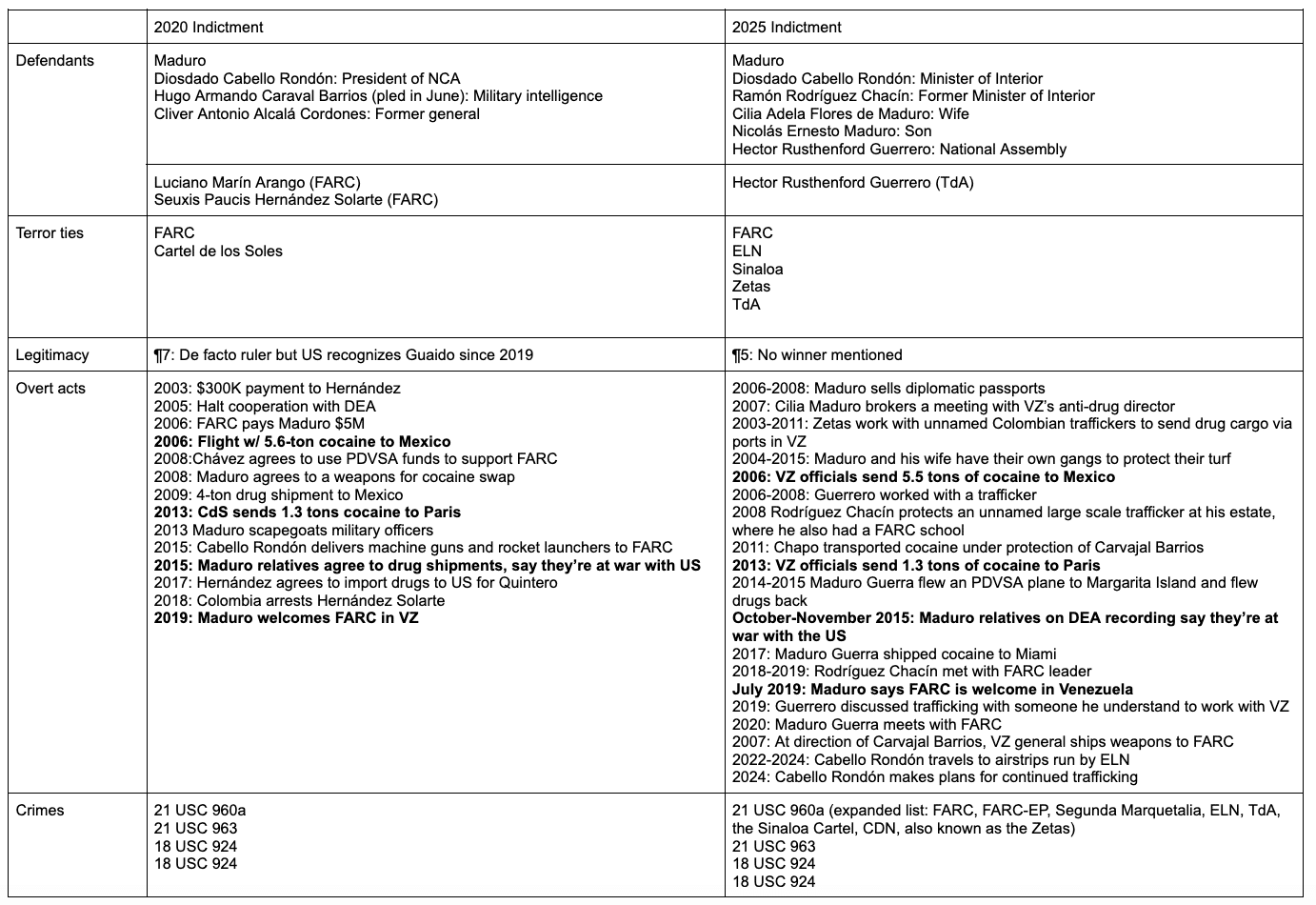

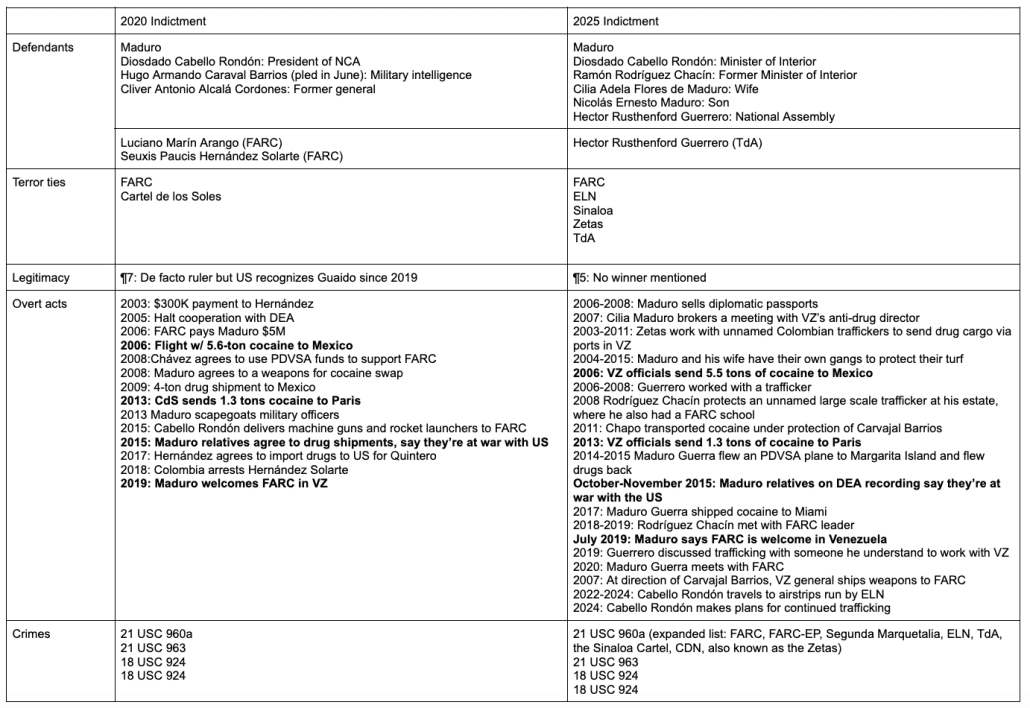

As I laid out here, I find it exceedingly unusual that DOJ laid out precisely what information got leaked and its classification level, described to be the following stories to which Natanson contributed.

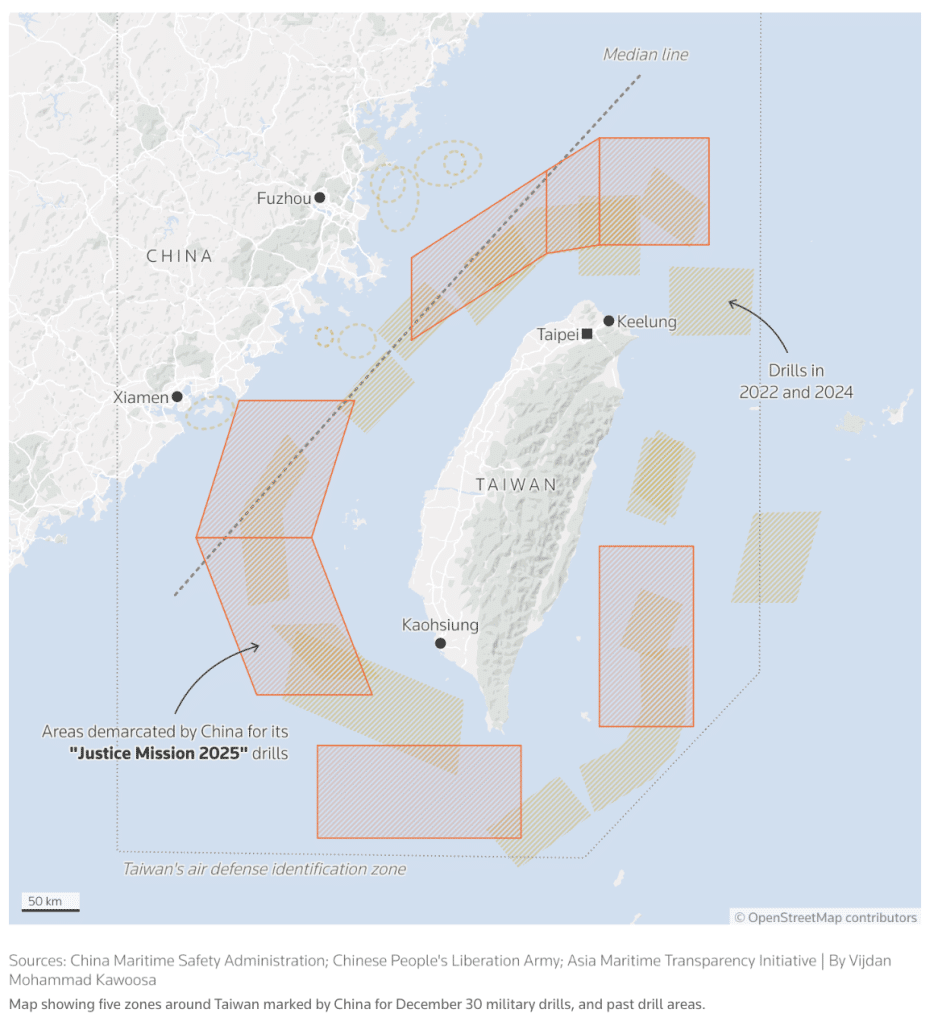

- This October 31, 2025 story about Venezuela asking Russia and China for security assistance included Top Secret/SCI/NOFORN information.

- This November 11, 2025 story about potential targets in a US attack included Secret/NOFORN information.

- This December 8, 2025 story about Maduro’s plans includes Confidential information.

- This January 6, 2026 story tallying 75 dead in Trump’s invasion includes Secret information.

- This January 9, 2026 story about an unsuccessful attempt to find an escape for Maduro includes Secret/NOFORN information.

Even as a legal issue, identifying the specific information that got leaked and how sensitive it is only serves to further compromise the information. It undermines prosecutors’ ability to prove that DOD (which is obscured in the indictment but which Pam Bondi freely identified) was trying to protect this information, a necessary element of the offense.

Seizing two MacBook Pros, an iPhone, a portable hard drive, her Garmin running watch, and a voice recorder from a journalist (while also sending WaPo a subpoena) when you already had proof that Perez-Lugones sent her classified information is more than overkill.

It’s the Garmin that really gets me. According to the declaration Natanson submitted in a bid to get her stuff back, she only communicated with Perez-Lugones via Signal or phone. The FBI is trying to obtain evidence about other people she met with, face-to-face.

So I want to consider what else DOJ might be looking for.

Did Perez-Lugones obtain proof of what Trump is really pursuing in Venezuela?

First, Garmin watch aside, it’s possible that Perez-Lugones took things that did not show up in Natanson’s reporting, yet, that DOJ is attempting to remove from her custody. The only thing classified at TS/SCI that Perez-Lugones is accused of leaking is a report based on an intercept of a letter Nicolás Maduro sent to Putin.

In mid-October, [Ramón Celestino] Velásquez, the transportation minister, traveled to Moscow for a meeting with his Russian counterpart, according to Russia’s Transport Ministry. According to documents obtained by The Post, he was also meant to deliver the letter from Maduro to Putin.

In the letter, Maduro requested that the Russians help boost his country’s air defenses, including restoring several Russian Sukhoi Su-30MK2 aircraft previously purchased by Venezuela. Maduro also asked for assistance overhauling eight engines and five radars in Russia, acquiring 14 sets of what were believed to be Russian missiles, as well as unspecified “logistical support,” according to the documents.

Maduro emphasized that Russian-made Sukhoi fighters “represented the most important deterrent the Venezuelan National Government had when facing the threat of war,” according to the U.S. records.

Maduro asked Russia for a “medium-term financing plan of three years” through Rostec, the Russian state-owned defense conglomerate. The documents did not specify an amount.

The documents also indicate that Velásquez was slated to meet with and deliver a second letter to Russian First Deputy Prime Minister Denis Manturov. They do not state whether or how the Russian government responded to Maduro’s outreach or whether the trip took place.

Nevertheless, DOJ successfully defeated an initial release order by citing all the TS/SCI information in Perez-Lugones’ brain.

Perez-Lugones is similarly positioned as the defendants in these cases: he has had decades of access to TS/SCI systems and, like these other defendants, what he knows is not erased simply because his access to the information ended. Further, like these defendants, because Perez-Lugones has “transcribed” and “photographed” highly classified information, it is likely he can recall it. Therefore, as the Government argued at the detention hearing, Perez-Lugones will be able to disseminate this information if released.

There is one document, classified Secret/Rel to NATO and identified as Document E, which Perez-Lugones allegedly photographed and sent to Natanson, that the indictment does not describe to be incorporated in this story including an account of an effort by the Pope to arrange an off-ramp for Maduro, the last of Natanson’s stories before his arrest.

On Christmas Eve, Cardinal Pietro Parolin, second-in-command to the pope and a longtime diplomatic mediator, urgently summoned Brian Burch, the U.S. ambassador to the Holy See, to press for details on America’s plans in Venezuela, according to government documents obtained by The Washington Post.

[snip]

For days, the influential Italian cardinal had been seeking access to Secretary of State Marco Rubio, the documents show, desperate to head off bloodshed and destabilization in Venezuela. In his conversation with Burch, a Trump ally, Parolin said Russia was ready to grant asylum to Maduro and pleaded with the Americans for patience in nudging the strongman toward that offer.

[snip]

In his Dec. 24 meeting with Burch, according to the documents obtained by The Post, Parolin said Russia was prepared to receive Maduro. He also shared what is described in the documents as a “rumor”: that Venezuela had become a “set piece” in Russia-Ukraine negotiations, and that “Moscow would give up Venezuela if it were satisfied on Ukraine.”

The materials Perez-Lugones shared are consistent with Trump having a quid pro quo with Russia, a swap of Venezuela for Ukraine. If he had obtained proof that he may or may not have shared, it might explain the need to seize any shred that he shared; but if so, the raid has nothing to do with national security, but instead with covering up Trump’s secret alliance with Russia.

A potentially related story describes that State was going to blow $50 million protecting Greenland’s polar bears, basically slush in support of Trump’s bid to conquer the entire hemisphere.

Is DOJ targeting specific whistleblowers, including Chuck Borges?

Remember how I noted that the new disclosures about DOGE’s unlawful access to Social Security data referenced an ongoing investigation?

“SSA first learned about this agreement during a review unrelated to this case in November 2025.”

WaPo was not the first outlet to report on Borges’ allegations of grave compromise of Social Security data, allegations that were partly confirmed by these recent disclosures; NYT was.

But WaPo, including Natanson, was the first outlet to interview Borges after he quit in October.

“Prove me wrong,” Borges told The Washington Post last week in his first media interview since his disclosure. “The only way I feel like we’re going to get to that point is with continued public interest, continued public pressure, and I’m willing to lend my name.”

Although he had until now avoided talking to the media, Borges told Post reporters that he had decided to go public to draw attention to his concerns about the safety of Americans’ data and his hope that the agency will share documentation to prove that the data wasn’t put at risk. At his Maryland home — decorated with photos of his family, his prolific board game collection and Navy paraphernalia — the self-described “data geek” said his fears while working at Social Security had kept him up at night.

And that interview linked several earlier WaPo articles, including an earlier Natanson one.

At the same time, the agency was exploring plans to lay off workers, and others were getting reassigned to jobs they were unfamiliar with or choosing to voluntarily leave. In those especially taxing days, Borges said, he saw co-workers breaking down in meetings or while sitting at their desks.

“I cannot count how many employees I saw cry, and that is at all levels of the agency, from executives downward,” Borges said.

In the summer, Borges first heard from colleagues that DOGE had transferred sensitive data to a cloud environment. He began to ask questions but got little information in response.

In Natanson’s Christmas Eve piece, she cited both a Social Security employee (the interview with Borges cites multiple others who back Borges’ claims, one of whom is Leland Dudek) and an IRS official who sent data to DOGE.

A Social Security employee: “Every piece of our data may be at the mercy of unscrupulous people.”

An IRS staffer: There is “a team figuring out how to get … data sent to Doge,” referring to the U.S. DOGE Service, Elon Musk’s cost-cutting team.

In short, DOJ may have raided Natanson in attempt to target a different whistleblower, one who went through formal channels to reveal an unprecedented assault on US person privacy.

Natanson’s sustained reporting of Trump’s dragnet

But it’s not just the Social Security data.

An earlier Natanson story described DOGE’s effort to effectively merge a bunch of massive government databases.

The U.S. DOGE Service is racing to build a single centralized database with vast troves of personal information about millions of U.S. citizens and residents, a campaign that often violates or disregards core privacy and security protections meant to keep such information safe, government workers say.

The team overseen by Elon Musk is collecting data from across the government, sometimes at the urging of low-level aides, according to multiple federal employees and a former DOGE staffer, who all spoke on the condition of anonymity for fear of reprisals. The intensifying effort to unify systems into one central hub aims to advance multiple Trump administration priorities, including finding and deporting undocumented immigrants and rooting out fraud in government payments. And it follows a March executive order to eliminate “information silos” as DOGE tries to streamline operations and cut spending.

At several agencies, DOGE officials have sought to merge databases that had long been kept separate, federal workers said. For example, longtime Musk lieutenant Steve Davis told staffers at the Social Security Administration that they would soon start linking various sources of Social Security data for access and analysis, according to a person briefed on the conversations, with a goal of “joining all data across government.” Davis did not respond to a request for comment.

Natanson was part of a story revealing the Postal Service is involved in the migrant dragnet.

The law enforcement arm of the U.S. Postal Service has quietly begun cooperating with federal immigration officials to locate people suspected of being in the country illegally, according to two people familiar with the matter and documents obtained by The Washington Post — dramatically broadening the scope of the Trump administration’s government-wide mass deportation campaign.

The U.S. Postal Inspection Service, a little-known police and investigative force for the mail agency, recently joined a Department of Homeland Security task force geared toward finding, detaining and deporting undocumented immigrants, said the people, who spoke on the condition of anonymity for fear of professional reprisals.

She revealed the effort to use Medicare data to target immigrants.

Trump immigration officials and the U.S. DOGE Service are seeking to use a sensitive Medicare database as part of their crackdown on undocumented immigrants, according to a person familiar with the matter and records obtained by The Washington Post.

And another describing how DOGE was using HUD data for a similar purpose.

At the Department of Housing and Urban Development, for example, officials are working on a rule that would ban mixed-status households — in which some family members have legal status and others don’t — from public housing, according to multiple staffers who spoke on the condition of anonymity out of fear of retribution.

These are some of Trump’s most egregious privacy violations, potentially the cornerstone of vast new data mining on Americans, including both immigrants (the ostensible focus) and citizens (clearly implicated in Borges’ allegations). If the Trump Administration believes Natanson has details about the real purpose of these data grabs, it might explain their raid of her devices: to prevent her from building on this reporting.

Relatedly, a Natanson story that should have generated more attention described how Trump is effectively trying to usurp DC’s policing sovereignty by boosting the numbers of Park Police.

The U.S. Park Police is seeking to double its ranks in D.C. over the next six months, according to documents obtained by The Washington Post detailing plans of an expansion that would bolster the federal agency’s role in the Trump administration’s crime crackdown in the nation’s capital.

[snip]

The Park Police website now boasts of a $70,000 hiring bonus, promotion potential and a “streamlined, virtual hiring process with quick turnaround.”

This was a one-off story. But it felt to me when I read it like a parallel to Stephen Miller’s creation of a national paramilitary force at ICE (the expansion of which has also been featured in Natanson reporting).

Like Natanson’s reporting on Trump’s data violations, this could reveal underlying plans for authoritarian power grabs.

Elon Musk’s corruption

Or maybe DOJ is after Natanson’s more general reporting on DOGE.

A number of her stories last year described how DOGE served to benefit Elon Musk and implant Musk’s businesses even more centrally in the Federal government.

One story last year (also relying on court filings and interviews) described all the agencies that Musk gained access while overseeing DOGE.

The Post reviewed court documents and interviewed dozens of current and former U.S. government officials to determine which records DOGE aides were able to examine while Musk led the unit. Reporters also spoke with experts and business competitors about how that information, if improperly shared with Musk’s companies, could give them a competitive advantage.

DOGE aides, for example, were given near-blanket access to records at the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, court records show. The agency holds proprietary information about algorithms used by payment apps similar to ones that Musk has said he wants to incorporate into his social media platform, X.

NASA employees told The Post that DOGE aides were able to review internal assessments of thousands of contracts, including those awarded to rivals of Musk’s SpaceX rocket company, which has already won billions of dollars of government work and is competing for more. (Among SpaceX’s competitors is Blue Origin, a company owned by Jeff Bezos, who also owns The Washington Post. Blue Origin and its executives did not respond to requests for comment.)

And Labor Department employees said in court filings that DOGE aides were allowed to examine any record at the agency, which holds files detailing dozens of sensitive workplace investigations into Tesla and other Musk companies as well as their competitors.

Another broke the story of how State was pushing foreign countries to adopt Starlink (which would put Musk at the center of a global surveillance network).

Less than two weeks after President Donald Trump announced 50 percent tariffs on goods from the tiny African nation of Lesotho, the country’s communications regulator held a meeting with representatives of Starlink.

The satellite business, owned by billionaire and Trump adviser Elon Musk’s SpaceX company, had been seeking access to customers in Lesotho. But it was not until Trump unveiled the tariffs and called for negotiations over trade deals that leaders of the country of roughly 2 million people awarded Musk’s firm the nation’s first-ever satellite internet service license, slated to last for 10 years.

[snip]

A series of internal government messages obtained by The Post reveal how U.S. embassies and the State Department have pushed nations to clear hurdles for U.S. satellite companies, often mentioning Starlink by name. The documents do not show that the Trump team has explicitly demanded favors for Starlink in exchange for lower tariffs. But they do indicate that Secretary of State Marco Rubio has increasingly instructed officials to push for regulatory approvals for Musk’s satellite firm at a moment when the White House is calling for wide-ranging talks on trade.

She was part of a series of stories on Starlink’s bid to replace an existing FAA contract.

So some of her many sources on DOGE last year exposed the corruption at the core of DOGE.

Obviously, DOJ could have targeted Natanson for no other reason than they want to go after all 1200 Signal contacts she had.

But whatever the reason, or reasons, the Aurelio Perez-Lugones seems like a pretext, a convenient national security case DOJ can invoke to try to identify thousands of whistleblowers, including whistleblowers who have firsthand evidence about the increasing authoritarianism of the Trump power grab.