Posts

Brett Kavanaugh Thinks that Jack Smith Is as Crazy as Ken Starr Was

/91 Comments/in 2020 Presidential Election, 2024 Presidential Election, Hunter Biden, January 6 Insurrection /by emptywheelThere was a subtle moment in yesterday’s SCOTUS hearing on Trump’s absolute immunity claim.

Former Whitewater prosecutor Brett Kavanaugh asked Michael Dreeben whether DOJ had weighed in on this prosecution.

Did the President weigh in? he asked. The Attorney General?

JUSTICE KAVANAUGH: As you’ve indicated, this case has huge implications for the presidency, for the future of the presidency, for the future of the country, in my view. You’ve referred to the Department a few times as having supported the position. Who in the Department? Is it the president, the attorney general?

MR. DREEBEN: The Solicitor General of the United States. Part of the way in which the special counsel functions is as a component of the Department of Justice.

The regulations envision that we reach out and consult. And on a question of this magnitude, that involves equities that are far beyond this prosecution, as the questions of the Court have —

JUSTICE KAVANAUGH: So it’s the solicitor general?

MR. DREEBEN: Yes.

Having been told that Jack Smith consulted with a Senate-confirmed DOJ official on these tough issues, Kavanaugh immediately launched into a screed about Morrison v. Olson, the circuit court decision that upheld the Independent Counsel statute.

JUSTICE KAVANAUGH: Okay. Second, like Justice Gorsuch, I’m not focused on the here and now of this case. I’m very concerned about the future. And I think one of the Court’s biggest mistakes was Morrison versus Olson.

MR. DREEBEN: Mm-hmm.

JUSTICE KAVANAUGH: I think that was a terrible decision for the presidency and for the country. And not because there were bad people who were independent counsels, but President Reagan’s administration, President Bush’s administration, President Clinton’s administration were really hampered —

MR. DREEBEN: Yes.

JUSTICE KAVANAUGH: — in their view —

MR. DREEBEN: Mm-hmm.

JUSTICE KAVANAUGH: — all three, by the independent counsel structure. And what I’m worried about here is that that was kind of let’s relax Article II a bit for the needs of the moment. And I’m worried about the similar kind of situation applying here. That was a prosecutor investigating a president in each of those circumstances. And someone picked from the opposite party, the current president and — usually —

MR. DREEBEN: Mm-hmm.

JUSTICE KAVANAUGH: — was how it worked. And Justice Scalia wrote that the — the fairness of a process must be adjudged on the basis of what it permits to happen —

Kavanaugh slipped here, and described the horror of “Presidents,” not former Presidents, routinely being subject to investigation going forward.

MR. DREEBEN: Mm-hmm.

JUSTICE KAVANAUGH: — not what it produced in a particular case. You’ve emphasized many times regularity, the Department of Justice. And he said: And I think this applied to the independent counsel system, and it could apply if presidents are routinely subject to investigation going forward. “One thing is certain, however. It involves investigating and perhaps prosecuting a particular individual. Can one imagine a less equitable manner of fulfilling the executive responsibility to investigate and prosecute? What would the reaction be if, in an area not covered by this statute, the Justice Department posted a public notice inviting applicants to assist in an investigation and possible prosecution of a certain prominent person? Does this not invite what Justice Jackson described as picking the man and then searching the law books or putting investigators to work to pin some offense on him? To be sure, the investigation must relate to the area of criminal offense” specified by the statute, “but that has often been and nothing prevents it from being very broad.” I paraphrased at the end because it was referring to the judges.

MR. DREEBEN: Mm-hmm. Yes.

JUSTICE KAVANAUGH: That’s the concern going forward, is that the — the system will — when former presidents are subject to prosecution and the history of Morrison versus Olson tells us it’s not going to stop. It’s going to — it’s going to cycle back and be used against the current president or the next president or — and the next president and the next president after that. All that, I want you to try to allay that concern. Why is this not Morrison v. Olson redux if we agree with you? [my emphasis]

Kavanaugh pretended, as he and others did throughout, that he wasn’t really suggesting this was a case of Morrison v. Olson redux; he was just talking hypothetically about the future.

JUSTICE KAVANAUGH: Right. No, I was just saying this is kind of the mirror image of that, is one way someone could perceive it, but I take your point about the different structural protections internally. And like Justice Scalia said, let me — I do not mean to suggest anything of the sort in the present case. I’m not talking about the present case. So I’m talking about the future.

This intervention came long after Kavanaugh suggested that charging Trump with defrauding the US for submitting fake election certificates and charging Trump with obstructing the vote certification after first charging hundreds of others with the same statute amounted to “creative” lawyering.

JUSTICE KAVANAUGH: Okay. For other official acts that the president may take that are not within that exclusive power, assume for the sake of argument this question that there’s not blanket immunity for those official acts but that to preserve the separation of powers, to provide fair notice, to make sure Congress has thought about this, that Congress has to speak clearly to criminalize official acts of the president by a specific reference. That seems to be what the OLC opinions suggest — I know you have a little bit of a disagreement with that — and what this Court’s cases also suggest.

JUSTICE KAVANAUGH: Well, it’s — isn’t — it’s a serious constitutional question whether a statute can be applied to the president’s official acts. So wouldn’t you always interpret the statute not to apply to the president, even under your formulation, unless Congress had spoken with some clarity?

MR. DREEBEN: I don’t think — I don’t think across the board that a serious constitutional question exists on applying any criminal statute to the president.

JUSTICE KAVANAUGH: The problem is the vague statute, you know, obstruction and 371, conspiracy to defraud the United States, can be used against a lot of presidential activities historically with a — a creative prosecutor who wants to go after a president.

But Kavanaugh returned to his insinuation that it was a stretch to prosecute a political candidate for submitting false certificates to Congress and the Archives under 18 USC 371 after his purported complaint about Morrison v. Olson.

Second, another point, you said talking about the criminal statutes, it’s very easy to characterize presidential actions as false or misleading under vague statutes. So President Lyndon Johnson, statements about the Vietnam War —

MR. DREEBEN: Mm-hmm.

JUSTICE KAVANAUGH: — say something’s false, turns out to be false that he says about the Vietnam War, 371 prosecution —

MR. DREEBEN: So —

JUSTICE KAVANAUGH: — after he leaves office?

None of this intervention made any sense; it wouldn’t even have made sense if offered by someone who hadn’t criminalized an abusive, yet consensual, blowjob for years.

After all, contrary to the demands of many, Merrick Garland didn’t appoint a Special Counsel until Trump declared himself a candidate. By that point, hundreds of people had already been charged under 18 USC 1512(c)(2) and DOJ was at least four months into Executive Privilege fights over testimony from Mike Pence’s aides and Trump’s White House counsel. Jack Smith was appointed nine months after Lisa Monaco publicly confirmed that DOJ was investigating the fake electors and six months after overt subpoenas focused on the scheme came out (to say nothing of the treatment of Rudy Giuliani’s phones starting a year earlier).

This is not a Morrison v. Olson issue.

Rather, Kavanaugh is using his well-established hatred for Morrison v. Olson to complain that Trump was investigated at all — and that, after such time that a conflict arose, Garland appointed a non-partisan figure to head the already mature investigation.

It was one of many examples yesterday where the aggrieved white men on the court vomited up false claims made by Trump.

Kavanaugh made no mention of the appointment of Robert Hur — not just a Republican but a Trump appointee who had deprived Andy McCabe of due process — to investigate Joe Biden for precisely the same crime for which Trump was charged. That’ll become pertinent at such time as Donald Trump’s claim to Jack Smith’s appointment gets to SCOTUS. After all, in that case, Trump will have been similarly treated as Joe Biden. In that case, Hur’s distinction between Biden’s actions and Trump’s should (but probably won’t) reassure the right wing Justices that Trump was not selectively prosecuted.

Speaking of things Kavanaugh didn’t mention, his false complaint — and which Clarence Thomas raised as well — comes at a curious time.

Because of Aileen Cannon’s dawdling, Trump’s challenge to Jack Smith’s appointment won’t get to SCOTUS for months, if ever.

But Hunter Biden, whose challenge to David Weiss’ appointment takes the same novel form as Trump’s — an appropriations clause challenge — may be before the Third Circuit as soon as next week. In a passage of Abbe Lowell’s response to Weiss’ demand that the Third Circuit give Lowell, an observant Jew, three days including Passover to establish jurisdiction for his interlocutory appeal, Lowell scolded Weiss for presuming to know the basis of his appeals.

The Special Counsel boasts that it prepared its motion in “two days” (Mot.Exped.3), but the legal errors that permeate its motion to dismiss only underscore why more time is needed to adequately research and thoughtfully brief the jurisdictional issues for this Court. The Special Counsel ignores numerous bases for jurisdiction (e.g., 28 U.S.C. §§ 1291 (collateral order doctrine), 1292(a)(1) (denial of Appropriations Clause injunction), and 1651 (mandamus)) over this appeal, and the legal claims it does make are flatly wrong, compare Mot.6 (falsely claiming “all Circuit Courts” reject reviewing denials of motions to enforce plea agreements as collateral orders), with United States v. Morales, 465 F. App’x 734, 736 (9th Cir. 2012) (“We also have jurisdiction over interlocutory appeals of orders denying a motion to dismiss an indictment on the ground that it was filed in breach of a plea agreement.”)

In addition to mandamus (suggesting they may either attack Judge Noreika’s immunity decision directly or ask the Third Circuit to order Delaware’s Probation Department to approve the diversion agreement that would give Hunter Biden immunity), Lowell also invoked an Appropriations clause injunction — basically an argument that Weiss is spending money he should not be.

Normally, this would never work and it’s unlikely to work here.

But even on the SCO challenge, there are a number of problems in addition to Lowell’s original complaint: that Weiss was appointed in violation of the rules requiring someone outside of DOJ to fill the role.

For example Weiss keeps claiming to be both US Attorney and Special Counsel at the same time (most obviously in claiming that tolling agreements signed as US Attorney were still valid as Special Counsel), or the newly evident fact that Weiss asked for Special Counsel status so that he could revisit a lead he was ordered to investigate — in the wake of Trump’s complaints to Bill Barr that Hunter Biden wasn’t being investigated diligently enough — back in 2020, a lead that incorporated Joe as well as Hunter Biden, a lead that uncovered an attempt to frame Joe Biden, an attempt to frame Joe Biden to which Weiss is a witness.

The oddities of Weiss’ investigation of Joe Biden’s son may even offer another claim that the right wing Justices claim to want to review. Jack Smith claims to have found only two or three charges with which Kavanaugh, who insists (former) Presidents can only be charged under statutes that formally apply to Presidents, would leave available to charge a President. But there’s one he missed: 26 USC 7217, which specifically prohibits the President from ordering up a tax investigation into someone, which Lowell invoked in his selective and vindictive prosecution claim. Lowell has not yet proven that Trump directly ordered tax officials, as opposed to Bill Barr and other top DOJ officials, to investigate Hunter Biden for tax crimes. But there’s a lot of circumstantial evidence that Trump pushed such an investigation. Certainly, statutes of limitation on Trump’s documented 2020 intrusions on the Hunter Biden investigation have not yet expired.

The Hunter Biden investigation has all the trappings of a politicized investigation that Kavanaugh claims to worry about — and with the Alexander Smirnov lead, it included Joe Biden, the Morisson v. Olson problem he claims to loathe.

That’s a made to order opportunity for Brett Kavanaugh to restrict such Special Counsel investigations.

Except, of course, it involves Democrats.

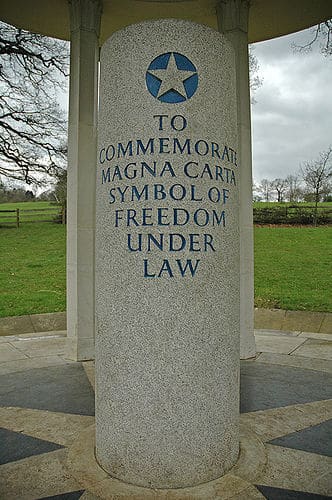

King John Would Like a Word with Justice Alito

/61 Comments/in 2020 Presidential Election, January 6 Insurrection, Law, SCOTUS, Trump Administration /by PeterrI am annoyed by folks who claim to love history and are blind to it. I am disgusted by folks who claim to love history, are willfully blind to it, and in their willful blindness try to use their power to inflict damage on others.

Why yes, I *did* listen to the oral arguments at SCOTUS today. Why do you ask?

sigh

Here’s an exchange between Justice Alito and Michael Dreeben, speaking for the government:

JUSTICE ALITO: Mr. Dreeben, you dispute the proposition that a former president has some form of immunity.

MR. DREEBEN: Mm-hmm.

JUSTICE ALITO: But, as I understand your argument, you do recognize that a former president has a form of special protection, namely, that statutes that are applicable to everybody must be interpreted differently under some circumstances when they are applied to a former president.

Isn’t that true?

MR. DREEBEN: It is true because, Justice Alito, of the general principle that courts construe statutes to avoid serious constitutional questions. And that has been the longstanding practice of the Office of Legal Counsel in the Department of Justice.

JUSTICE ALITO: All right. So this is more, I think, than just a — a quarrel about terminology, whether what the former president gets is some form of immunity or some form of special protection because it involves this difference which I’m sure you’re very well aware of.

If it’s just a form of special protection, in other words, statutes will be interpreted differently as applied to a former president, then that is something that has to be litigated at trial. The — the former president can make a motion to dismiss and may cite OLC opinions, and the district court may say: Well, that’s fine, I’m not bound by OLC and I interpret it differently, so let’s go to trial.

And then there has to be a trial, and that may involve great expense and it may take up a lot of time, and during the trial, the — the former president may be unable to engage in other activities that the former president would want to engage in. And then the outcome is dependent on the jury, the instructions to the jury and how the jury returns a verdict, and then it has to be taken up on appeal.

So the protection is greatly diluted if you take the form — if it takes the form that you have proposed. Now why is that better?

MR. DREEBEN: It’s better because it’s more balanced. The — the blanket immunity that Petitioner is arguing for just means that criminal prosecution is off the table, unless he says that impeachment and conviction have occurred.

Oh, the horrors of forcing a former president to defend himself in a trial! So sayeth Justice Alito, he who cites a 17th century English witchburner of a jurist (who also invented the marital rape exception), in order to justify denying women bodily autonomy.

If Justice Alito is fond of citing old English judicial writings, let me walk him back another 4 centuries and introduce him to John, by the grace of God King of England, Lord of Ireland, Duke of Normandy and Aquitaine, and Count of Anjou.

Once upon a time — long before a bunch of rabble-rousing colonial insurrectionists said that “Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, –That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness.” — there was a little dustup between John, by the grace of God King of England etc., and a bunch of his barons, as well as various bishops and archbishops. The barons and clergy, distressed at what seemed to them to be very ill treatment at the hand of their king, expressed their frustrations in a manner that could not be ignored.

In June 1215, John and the barons negotiated an agreement. In it, after an introduction and 60 separate clauses in which King John agreed to various reforms and promised to make specific restitution in various particular cases that were demanded by his barons, the 1215 version of the Magna Carta ends like this:

* (61) SINCE WE [ed: John] HAVE GRANTED ALL THESE THINGS for God, for the better ordering of our kingdom, and to allay the discord that has arisen between us and our barons, and since we desire that they shall be enjoyed in their entirety, with lasting strength, for ever, we give and grant to the barons the following security:

The barons shall elect twenty-five of their number to keep, and cause to be observed with all their might, the peace and liberties granted and confirmed to them by this charter.

If we, our chief justice, our officials, or any of our servants offend in any respect against any man, or transgress any of the articles of the peace or of this security, and the offence is made known to four of the said twenty-five barons, they shall come to us – or in our absence from the kingdom to the chief justice – to declare it and claim immediate redress. If we, or in our absence abroad the chief justice, make no redress within forty days, reckoning from the day on which the offence was declared to us or to him, the four barons shall refer the matter to the rest of the twenty-five barons, who may distrain upon and assail us in every way possible, with the support of the whole community of the land, by seizing our castles, lands, possessions, or anything else saving only our own person and those of the queen and our children, until they have secured such redress as they have determined upon. Having secured the redress, they may then resume their normal obedience to us.

Any man who so desires may take an oath to obey the commands of the twenty-five barons for the achievement of these ends, and to join with them in assailing us to the utmost of his power. We give public and free permission to take this oath to any man who so desires, and at no time will we prohibit any man from taking it. Indeed, we will compel any of our subjects who are unwilling to take it to swear it at our command.

If one of the twenty-five barons dies or leaves the country, or is prevented in any other way from discharging his duties, the rest of them shall choose another baron in his place, at their discretion, who shall be duly sworn in as they were.

In the event of disagreement among the twenty-five barons on any matter referred to them for decision, the verdict of the majority present shall have the same validity as a unanimous verdict of the whole twenty-five, whether these were all present or some of those summoned were unwilling or unable to appear.

The twenty-five barons shall swear to obey all the above articles faithfully, and shall cause them to be obeyed by others to the best of their power.

We will not seek to procure from anyone, either by our own efforts or those of a third party, anything by which any part of these concessions or liberties might be revoked or diminished. Should such a thing be procured, it shall be null and void and we will at no time make use of it, either ourselves or through a third party.

* (62) We have remitted and pardoned fully to all men any ill-will, hurt, or grudges that have arisen between us and our subjects, whether clergy or laymen, since the beginning of the dispute. We have in addition remitted fully, and for our own part have also pardoned, to all clergy and laymen any offences committed as a result of the said dispute between Easter in the sixteenth year of our reign (i.e. 1215) and the restoration of peace.

In addition we have caused letters patent to be made for the barons, bearing witness to this security and to the concessions set out above, over the seals of Stephen archbishop of Canterbury, Henry archbishop of Dublin, the other bishops named above, and Master Pandulf.

* (63) IT IS ACCORDINGLY OUR WISH AND COMMAND that the English Church shall be free, and that men in our kingdom shall have and keep all these liberties, rights, and concessions, well and peaceably in their fullness and entirety for them and their heirs, of us and our heirs, in all things and all places for ever.

Both we and the barons have sworn that all this shall be observed in good faith and without deceit. Witness the abovementioned people and many others.

Given by our hand in the meadow that is called Runnymede, between Windsor and Staines, on the fifteenth day of June in the seventeenth year of our reign (i.e. 1215: the new regnal year began on 28 May).

Note the third paragraph, that begins “If we, our chief justice, . . .” In that paragraph, King John, by the grace of God King of England etc., is agreeing that he and his administration are not immune from accountability.

John and the barons agreed on a process for adjudicating disputes. They agreed on a panel that could both bring charges and judge them. They agreed on how the panel should be chosen, and how the panel should select new members at the death of old ones. They agreed on how many members of the panel needed to agree in order for a judgment to be final. They agreed on a time frame for restitution. Most importantly, should John be found to have violated the terms of this document and yet refuse restitution, John, by the grace of God King of England etc., agreed that his castles and lands could be seized under order of the panel to make restitution for what he had done, or his officials had done on his behalf.

To be fair, the Magna Carta was changed and altered in the years and centuries that followed. But the original text of the original version makes it clear that even the King of England, Lord of Ireland, Duke of Normandy and Aquitaine, and Count of Anjou does not enjoy absolute immunity.

Trump may wish to be a monarch with absolute immunity and not a president.

Alito may wish to treat him as a monarch with absolute immunity and not a president.

But in a meadow at Runnymede, between Windsor and Staines, John, by the grace of God King of England, Lord of Ireland, Duke of Normandy and Aquitaine, and Count of Anjou, said no. That’s not how even a divinely appointed monarch is to be treated.

Sam Alito Says that Donald Trump Is a Maligned Ham Sandwich

/197 Comments/in 2020 Presidential Election, January 6 Insurrection /by emptywheelI’m not, now, as full of despair as I was at one point in the SCOTUS hearing on Presidential immunity. (Here’s my live thread.) I believe that a majority of the court will rule that for private conduct — adopting the Blassingame rule that a President acting as candidate acts in a private role — a former President can be prosecuted.

But whooboy, Sam Alito really really believes everything Trump has said about this being a witch hunt. He repeatedly said that the protections that we assume ensure rule of law in the US — DOJ guidelines on prosecutions, the role of a grand jury, the role of a judge — are not enough in the case of Donald Trump. Sam Alito believes that Donald Trump should not have to be inconvenienced by a trial while he could be doing something else. Sam Alito also believes that January 6 was a mostly peaceful protest.

Alito even suggested that a President would be more likely to engage in violence after a closely contested election if he knew he might be prosecuted for it than not.

It was fairly insane.

Meanwhile, while I think there’s a majority (though Steve Vladeck is not as convinced) — with at least all the women in a majority — to let this case proceed at least on the private acts alleged in the indictment (with the huge caveat that Trump’s demands of Pence would not be considered a private act!), it’s clear that Neil Gorsuch doesn’t see how 18 USC 1512(c)(2) could be applied to Trump because we don’t know what corrupt purpose is, even though, of all the January 6 defendants, his corrupt purpose — his effort to obtain a improper private benefit — is most clearcut.

But there’s a whole lot of garbage that will come out of this decision, including immunity for core actions, like pardons and appointments, that could clearly be part of a bribe.

Notably, both Clarence Thomas and Brett Kavanaugh appear to be gunning for Special Counsels (though possibly only with respect to Presidents, not the sons of Presidents).

Michael Dreeben backtracked and backtracked far enough to preserve a case. But it’s not sure what else there will be.

When Michael Dreeben Accepted John Sauer’s Invitation to Talk about Speech and Debate

/107 Comments/in 2020 Presidential Election, January 6 Insurrection /by emptywheelTrump’s appeal of Judge Tanya Chutkan’s immunity opinion is interesting for the personnel involved. The briefs repeat the very same arguments — and in some instances, include the same passages almost verbatim — made less than three months ago. But first Trump brought in John Sauer to argue his appellate cases, then in the last few weeks, former Deputy Solicitor General Michael Dreeben quietly joined the Special Counsel team (importantly, the Solicitor General appointed by Joe Biden has no role in this appeal).

That makes any changes in the arguments of particular interest, because accomplished appellate lawyers saw fit to add them.

Admittedly, two things happened in the interim to change the landscape significantly. In Blassingame, issued hours before Chutkan released her order, DC Circuit Chief Judge Sri Srinivasan laid out how a President running for reelection does not act in his official duty. In Meadows, 11th Circuit Chief Judge William Pryor adopted that analysis in the criminal context with regards to Mark Meadows in the Georgia case.

That provided both sides the opportunity to address what I had argued, on October 21, was a real weakness in Jack Smith’s first response: the relative silence on the extent to which Trump’s actions were not part of his official duties.

In total, DOJ’s more specific arguments take up just six pages of the response. I fear it does not do as much as it could do in distinguishing between the role of President and political candidate, something that will come before SCOTUS — and could get there first — in the civil suits against Trump.

Citing both Blassingame and Meadows, Smith and Dreeben invited the DC Circuit to rule narrowly if it chose, finding that the crimes alleged in the indictment all pertain to Trump’s role as candidate.

The Court need not address those issues here, however. The indictment alleges a conspiracy to overturn the presidential election results, JA.26, through targeting state officials, id. at 32-44; creating fraudulent slates of electors in seven states, id. at 44-50; leveraging the Department of Justice in the effort to target state officials through deceit and to substitute the fraudulent elector slates supporting his personal candidacy for the legitimate ones, id. at 50-54; attempting to enlist the Vice President to fraudulently alter the election results during the certification proceeding on January 6, 2021, and directing supporters to the Capitol to obstruct the proceeding, id. at 55-62; and exploiting the violence and chaos that transpired at the United States Capitol on January 6, 2021, id. at 62-65. The indictment thus alleges conspiracies to advance the defendant’s prospects as a candidate for elective office in concert with private persons as well as government officials, cf. Blassingame, 87 F.4th at 4 (the President’s conduct falls beyond the outer perimeter of his official duties if it can only be understood as having been undertaken in his capacity as a candidate for re-election), and the defendant offers no plausible argument that the federal government function and official proceeding that he is charged with obstructing establish a role—much less an exclusive and conclusive role—for the President, see Georgia v. Meadows, No. 23-12958, 2023 WL 8714992, at *11 (11th Cir. Dec. 18, 2023); United States v. Rhodes, 610 F. Supp. 3d 29, 41 (D.D.C. 2022) (Congress and the Vice President in his role as President of the Senate carry out the “laws governing the transfer of power”) (internal quotation marks omitted).

The short term goal here is to convince Judge Karen Henderson, the Poppy Bush appointee on this panel whose judicial views have grown as radical as any Trump appointee’s, to reject Trump’s claims. Ultimately, Jack Smith is arguing against Presidential immunity even for official acts, but a ruling limited to acts taken as a candidate might provide a way to get Judge Henderson to join the two Biden appointees on the panel, Florence Pan and Michelle Childs, in rejecting Trump’s immunity claims.

In both his briefs, Trump had — ridiculously! — argued that Nixon’s Watergate actions were private acts yet Trump’s January 6 actions were part of his official duties. Smith swatted that claim away in a passage noting that Nixon’s acceptance of a pardon served as precedent for the notion that a President could be tried for actions done as President.

That President Nixon was named as an unindicted coconspirator in a plot to defraud the United States and obstruct justice, Nixon, 418 U.S. at 687, entirely refutes the defendant’s efforts (Br.27-28, 41) to distinguish that case as involving private conduct. See United States v. Haldeman, 559 F.2d 31, 121-22 (D.C. Cir. 1976) (en banc) (per curiam) (explaining that the offense conduct included efforts “to get the CIA to interfere with the Watergate investigation being conducted by the FBI” and “to obtain information concerning the investigation from the FBI and the Department of Justice”) (internal quotation marks omitted). And President Nixon’s acceptance of the pardon represents a “confession of guilt.” Burdick v. United States, 236 U.S. 79, 90-91 (1915).

Again, once the categorization adopted by Srinivasan is available, it makes the comparison with Nixon far more damning.

One of the most interesting additions to the earlier arguments, however, is that Sauer added a second kind of immunity to Trump’s earlier discussion that the principles of judicial immunity carry over to Presidential immunity: Speech and Debate. In two cursory paragraphs, Sauer claimed that, like members of Congress, Trump should enjoy both civil and criminal immunity for their official, “legislative” acts.

Legislative immunity. Legislative immunity encompasses the “privilege … to be free from arrest or civil process” for legislative acts, i.e., criminal and civil proceedings alike. Tenney, 341 U.S. at 372. Such immunity enables officials “to execute the functions of their office without fear of prosecutions, civil or criminal.” Id. at 373–74 (quoting Coffin v. Coffin, 4 Mass. 1, 27 (Mass. 1808)).

Thus, legislative immunity “prevent[s]” legislative acts “from being made the basis of a criminal charge against a member of Congress.” Johnson, 383 U.S. at 180. A legislative act “may not be made the basis for a civil or criminal judgment against a Member [of Congress] because that conduct is within the sphere of legitimate legislative activity.” Gravel v. United States, 408 U.S. 606, 624 (1972) (emphasis added). Speech and Debate immunity “protects Members against prosecutions that directly impinge upon or threaten the legislative process.” Id. at 616.

Did I say two developments have changed the landscape of this discussion? I’m sorry, I should have added a third: In response to the September DC Circuit remand of Scott Perry’s appeal of Judge Beryl Howell’s decision that Jack Smith could have some stuff from his phone — in a panel including Henderson — on December 19, Howell’s successor at Chief Judge, James Boasberg reviewed the contested files anew and ruled that Smith could have most of them, including communications pertaining to “efforts to work with or influence members of the Executive Branch.”

Subcategories (c), (d), (e), and (f) comprise communications about non-legislative efforts to work with or influence members of the Executive Branch. Even if such activities are “in a day’s work for a Member of Congress,” the Speech or Debate Clause “does not protect acts that are not legislative in nature.”

Kyle Cheney (who snagged an accidentally posted filing before it was withdrawn) described what many of those communications would include, including Perry’s advance knowledge of Trump’s efforts to install Jeffrey Clark as Attorney General.

Boasberg’s order required Perry to turn over those communications by December 27; if he appealed that decision, I’m not aware of it. So as you read this Speech and Debate section, consider the likelihood that Jack Smith finally obtained records from a member of Congress DOJ has been seeking for 17 months, since before Smith was appointed.

The DC Circuit opinion in Perry is not mentioned in any of these briefs. But the developments provide an interesting backdrop for Dreeben’s much longer response to Sauer’s half-hearted Speech and Debate bid. Much of it is an originalist argument, noting that whereas Speech and Debate was explicitly included in the Constitution, immunity for Presidents was not, not even in a landscape where Delaware and Virginia had afforded their Executive such immunity.

Along the way, Dreeben includes two citations that weren’t in Jack Smith’s original submission: One from Clarence Thomas making just that originalist argument about Presidential immunity: “the Constitution explicitly addresses the privileges of some federal officials, but it does not afford the President absolute immunity.” And one from Karen Henderson, the key vote in this panel, noting that, contra Sauer’s expansive immunity claim, “it is well settled that a Member is subject to criminal prosecution and process.”

Unlike the explicit textual immunity granted to legislators under the Speech or Debate Clause, U.S. Const. art. I, § 6, cl. 1, which provides that “for any Speech or Debate in either House,” members of Congress “shall not be questioned in any other Place,” the Constitution does not expressly provide such protection for the President or any executive branch officials. See Vance, 140 S. Ct. at 2434 (Thomas, J., dissenting) (“The text of the Constitution explicitly addresses the privileges of some federal officials, but it does not afford the President absolute immunity.”); JA.604-06. By contrast, state constitutions at the time of the founding in Virginia and Delaware did grant express criminal immunity to the state’s chief executive officer. JA.605 (citing Saikrishna Bangalore Prakash, Prosecuting and Punishing Our Presidents, 100 Tex. L. Rev. 55, 69 (2021)). To be sure, the federal Constitution’s “silence . . . on this score is not dispositive,” Nixon, 418 U.S. at 705 n.16, but that silence is telling when placed against the Constitution’s Impeachment Judgment Clause, which presupposes and expressly preserves the availability of criminal prosecution following impeachment and conviction. See U.S. Const. art. I, § 3, cl. 7.

[snip]

The defendant suggests (Br.16-17, 18-19) that common-law principles of legislative immunity embodied in the Speech or Debate Clause, U.S. Const. art. I, § 6, cl. 1, inform the immunity analysis here, but that suggestion lacks support in constitutional text, history, or purpose. The Framers omitted any comparable text protecting executive officials, see Vance, 140 S. Ct. at 2434 (Thomas, J., dissenting), and no reason exists to look to the Speech or Debate Clause as a model for the defendant’s immunity claim.

In contrast to the defendant’s sweeping claim of immunity for all Presidential acts within the outer perimeter of his duties, the Speech or Debate Clause’s scope is specific: it is limited to conduct “within the ‘sphere of legitimate legislative activity.’” Gravel v. United States, 408 U.S. 606, 624 (1972). “Legislative acts are not all-encompassing,” and exclude a vast range of “acts in [a Member’s] official capacity,” such as outreaches to the Executive Branch. Id. Beyond that limitation, the Clause “does not purport to confer a general exemption . . . from liability . . . in criminal cases.” Id. at 626. Nor does it “privilege [Members or aides] to violate an otherwise valid criminal law in preparing for or implementing legislative acts.” Id. Courts have therefore recognized for more than 200 years that a Representative “not acting as a member of the house” is “not entitled to any privileges above his fellow-citizens” but instead “is placed on the same ground, on which his constituents stand.” Coffin v. Coffin, 4 Mass. 1, 28-29 (1808); see Rayburn House Off. Bldg., 497 F.3d at 670 (Henderson, J., concurring in the judgment) (observing that “it is well settled that a Member is subject to criminal prosecution and process”). The Speech or Debate Clause does not “make Members of Congress super-citizens, immune from criminal responsibility.” United States v. Brewster, 408 U.S. 501, 516 (1972). The defendant’s immunity claim, however, would do just that, absent prior impeachment and conviction.

The Speech or Debate Clause’s historical origins likewise reveal its inapplicability in the Presidential context. The Clause arose in response to successive British kings’ use of “the criminal and civil law to suppress and intimidate critical legislators.” United States v. Johnson, 383 U.S. 169, 178 (1966); see United States v. Gillock, 445 U.S. 360, 368-69 (1980) (noting that the English parliamentary privilege arose from “England’s experience with monarchs exerting pressure on members of Parliament” in order “to make them more responsive to their wishes”). In one instance, the King “imprison[ed] members of Commons on charges of seditious libel and conspiracy to detain the Speaker in the chair to prevent adjournment,” and the judiciary afforded no relief because “the judges were often lackeys of the Stuart monarchs.” Johnson, 383 U.S. at 181. That history has no parallel here: the defendant can point to no record of abuses of the criminal law against former Presidents, and the Article III judiciary provides a bulwark against any such abuses. [my emphasis]

Having been invited to discuss congressional immunity, Smith’s brief cites another comment from Henderson’s Rayburn concurrence elsewhere. “[T]he laws of this country allow no place or employment as a sanctuary for crime.”

see United States v. Rayburn House Off. Bldg., 497 F.3d 654, 672-73 (D.C. Cir. 2007) (Henderson, J., concurring in the judgment) (“[T]he laws of this country allow no place or employment as a sanctuary for crime.”) (citing Williamson v. United States, 207 U.S. 425, 439 (1908)). [my emphasis]

Tactically, all this is just an argument — an originalist argument — that even an immunity explicitly defined in the Constitution, Speech and Debate, does not — Judge Karen Henderson observed in 2007, when the question of immunity pertained to Black Democrat William Jefferson, in a case in which she sided with DOJ attorney Michael Dreeben — exempt anyone from criminal prosecution. Read her concurrence! She makes the same arguments about Tudor kings that Smith and Dreeben make!

But much of Jack Smith’s response, in my opinion, lays the ground work for other, future appeals. For example, this brief adopts a slight change in the way it describes the fake elector plot, emphasizing the centrality of Trump, “caus[ing his fake electors] to send false certificates to Congress,” a move that may be a preemptive response to any narrowing of 18 USC 1512(c)(2) that SCOTUS plans in the Fischer appeal of obstruction’s use for January 6.

Ultimately, Smith is still arguing for a broader ruling, rejecting Trump’s presidential immunity claims more generally. Ultimately, I imagine this adoption of language from Clinton v Jones is where Jack Smith would like to end up.

Given that, the Constitution cannot be understood simultaneously (and implicitly) to immunize a former President from criminal prosecution for official acts; rather, the Constitution envisions Presidential accountability in his political capacity through impeachment and in his personal capacity through prosecution. See Clinton, 520 U.S. at 696 (“[F]ar from being above the laws, [the President] is amenable to them in his private character as a citizen, and in his public character by impeachment.”) (quoting 2 J. Elliot, Debates on the Federal Constitution 480 (2d ed. 1863) (James Wilson)).

To get there without possibly fatal delays, though, Dreeben and Smith need to get Henderson to agree to at least a narrow rejection of Trump’s immunity claims.

And so, responding to Sauer’s invitation, Dreeben reminded Henderson of what she said about a case he argued 16 years ago.

But if I were Scott Perry, three days after he was ordered to turn over records about his plotting with Donald Trump to overturn the election, I’d be watching these arguments closely.

What Jack Smith Didn’t Say in His Double Jeopardy Response

/63 Comments/in 2020 Presidential Election, 2024 Presidential Election, January 6 Insurrection /by emptywheelJack Smith just submitted his response to Trump’s immunity claims before the DC Circuit.

While most attention will be on the absolute immunity claims, given the disqualification of Trump in Colorado and Maine, I’m more interested in Smith’s response to Trump’s claim that his impeachment acquittal precludes these charges.

That’s because, depending on how this appeal goes, Jack Smith could make the question of Trump’s (dis)qualification much easier by superseding this indictment with an insurrection charge.

Most of the response argues that impeachment and criminal charges are different things. That argument is likely to prevail by itself.

In addition, though, the response repeated a passage, almost verbatim, that appeared in Smith’s response before Chutkan. In it, Smith said that the elements of offense currently charged do not overlap with the elements of offense for an insurrection charge.

Any double-jeopardy claim here would founder in light of these principles. Without support, the defendant asserts that his Senate acquittal and the indictment in this case involve “the same or closely related conduct.” Br.52. Not so. The single article of impeachment alleged a violation of “Incitement of Insurrection,” H.R. Res. 24, 117th Cong. at 2 (Jan. 11, 2021) (capitalization altered), and charged that the defendant had “incit[ed] violence against the Government of the United States,” id. at 3. The most analogous federal statute is 18 U.S.C. § 2383, which prohibits “incit[ing] . . . any rebellion or insurrection against the authority of the United States or the laws thereof.” A violation of Section 2383 would therefore require proof that the violence at the Capitol on January 6, 2021, constituted an “insurrection against the authority of the United States or the laws thereof” and that the defendant incited that insurrection. Incitement, in turn, requires proof that the speaker’s words were both directed to “producing imminent lawless action” and “likely to incite or produce such action.” Brandenburg v. Ohio, 395 U.S. 444, 447 (1969) (per curiam); NAACP v. Claiborne Hardware Co., 458 U.S. 886, 927-28 (1982). None of the offenses charged here—18 U.S.C. § 371, 18 U.S.C. § 1512(c)(2) and (k), and 18 U.S.C. § 241—has as an element any of the required elements for an incitement offense. And the elements of the charged offenses—e.g., conspiring to defeat a federal governmental function through deceit under Section 371, obstruct an “official proceeding” under Section 1512, and deprive persons of rights under Section 241—are nowhere to be found in the elements of a violation of Section 2383 or any other potential incitement offense. The mere fact that some of the conduct on which the impeachment resolution relied is related to conduct alleged in the indictment does not implicate the Double Jeopardy Clause or its principles. See Dixon, 509 U.S. at 696.

This doesn’t mean that Smith will supersede Trump, if this appeal succeeds. There are a lot of reasons not to do so (including that Trump would get to file a motion to dismiss that charge).

That said, Smith might have another reason to do so if SCOTUS significantly narrowed the obstruction charge in the Fischer appeal, because the obstruction charge is how Smith is presenting the evidence that Trump caused the attack on the Capitol.

In my view, this language keeps options open.

Jack Smith (and Michael Dreeben) Go to SCOTUS

/127 Comments/in 2020 Presidential Election, January 6 Insurrection /by emptywheelJack Smith just skipped the DC Circuit to ask for cert on Trump’s absolutely immunity claim.

Here’s the argument Smith gives for taking the case directly:

A cornerstone of our constitutional order is that no person is above the law. The force of that principle is at its zenith where, as here, a grand jury has accused a former President of committing federal crimes to subvert the peaceful transfer of power to his lawfully elected successor. Nothing could be more vital to our democracy than that a President who abuses the electoral system to remain in office is held accountable for criminal conduct. Yet respondent has asserted that the Constitution accords him absolute immunity from prosecution. The Constitution’s text, structure, and history lend no support to that novel claim. This Court has accorded civil immunity for a President’s actions within the outer perimeter of his official responsibilities, see Nixon v. Fitzgerald, 457 U.S. 731 (1982), and the Executive Branch has long held the view that a sitting President cannot be indicted while in office. But those principles cannot be extended to provide the absolute shield from criminal liability that respondent, a former President, asserts. Neither the separation of powers nor respondent’s acquittal in impeachment proceedings lifts him above the reach of federal criminal law. Like other citizens, he is accountable for criminal conduct.

[snip]

The United States recognizes that this is an extraordinary request. This is an extraordinary case. The Court should grant certiorari and set a briefing schedule that would permit this case to be argued and resolved as promptly as possible.

Posting this here for now. I’ll update in a bit.

An interesting detail: Michael Dreeben somehow snuck into Jack Smith’s office. He was Mueller’s appellate guy.

Bill Barr Defended Yevgeniy Prigozhin Last Night

/48 Comments/in 2016 Presidential Election, Mueller Probe /by emptywheelWhile he didn’t do so explicitly and may not have the clarity of thought to even realize it, but in his screed at radical right wing Hillsdale College, Bill Barr effectively defended Yevgeniy Prigozhin’s attempts to interfere in American elections.

That’s because — in a speech attacking Robert Mueller’s work — he took an extended swipe at exotic interpretations of law.

In recent years, the Justice Department has sometimes acted more like a trade association for federal prosecutors than the administrator of a fair system of justice based on clear and sensible legal rules. In case after case, we have advanced and defended hyper-aggressive extensions of the criminal law. This is wrong and we must stop doing it.

The rule of law requires that the law be clear, that it be communicated to the public, and that we respect its limits. We are the Department of Justice, not the Department of Prosecution.

We should want a fair system with clear rules that the people can understand. It does not serve the ends of justice to advocate for fuzzy and manipulable criminal prohibitions that maximize our options as prosecutors. Preventing that sort of pro-prosecutor uncertainty is what the ancient rule of lenity is all about. That rule should likewise inform how we at the Justice Department think about the criminal law.

Advocating for clear and defined prohibitions will sometimes mean we cannot bring charges against someone whom we believe engaged in questionable conduct. But that is what it means to have a government of laws and not of men. We cannot let our desire to prosecute “bad” people turn us into the functional equivalent of the mad Emperor Caligula, who inscribed criminal laws in tiny script atop a tall pillar where nobody could see them.

To be clear, what I am describing is not the Al Capone situation — where you have someone who committed countless crimes and you decide to prosecute him for only the clearest violation that carries a sufficient penalty. I am talking about taking vague statutory language and then applying it to a criminal target in a novel way that is, at a minimum, hardly the clear consequence of the statutory text.

[snip]

The Justice Department abets this culture of criminalization when we are not disciplined about what charges we will bring and what legal theories we will bless. Rather than root out true crimes — while leaving ethically dubious conduct to the voters — our prosecutors have all too often inserted themselves into the political process based on the flimsiest of legal theories. We have seen this time and again, with prosecutors bringing ill-conceived charges against prominent political figures, or launching debilitating investigations that thrust the Justice Department into the middle of the political process and preempt the ability of the people to decide.

This criminalization of politics will only worsen until we change the culture of concocting new legal theories to criminalize all manner of questionable conduct. Smart, ambitious lawyers have sought to amass glory by prosecuting prominent public figures since the Roman Republic. It is utterly unsurprising that prosecutors continue to do so today to the extent the Justice Department’s leaders will permit it.

As long as I am Attorney General, we will not.

Our job is to prosecute people who commit clear crimes. It is not to use vague criminal statutes to police the mores of politics or general conduct of the citizenry. Indulging fanciful legal theories may seem right in a particular case under particular circumstances with a particularly unsavory defendant—but the systemic cost to our justice system is too much to bear.

He even ad-libbed a comment to more specifically attack Michael Dreeben, the top member of the Solicitor General’s office, who was a member of the Mueller team.

The Obama administration had some of the people who were in Mueller’s office writing their briefs in the Supreme Court, so maybe that explains something.

Mueller considered a range of exotic applications of law.

He considered charging Don Jr for accessing a private website using the password provided by people associated with WikiLeaks. But he didn’t charge the failson, arguing the intent wasn’t there.

He considered charging Don Jr. for accepting an offer of campaign dirt from a foreigner, Aras Agalarov. He didn’t charge it, in part, because Don Jr is too stupid to know that accepting campaign help from foreigners is illegal.

Mueller considered charging Roger Stone for accepting campaign assistance from foreigners Julian Assange and the GRU in the form of stolen emails. He didn’t charge it, in part for First Amendment reasons.

Every other charge, save one, was a routine application of law:

- George Papadopoulos, for lying to the FBI about when he got offered campaign dirt

- Mike Flynn, for lying to the FBI about undermining sanctions imposed on Russia for interfering in the election and lying to DOJ about having secretly worked for the Turkish government

- Paul Manafort and Rick Gates, for money laundering, cheating his taxes, lying to DOJ on a FARA form, and (in Manafort’s case) trying to get witnesses to lie

- Michael Cohen, for lying to Congress about the lucrative business deal Trump was chasing during the election

- Roger Stone, for lying to Congress about a lot of things, including that he kept the campaign informed of his efforts to optimize the data stolen by Russian intelligence officers, as well as for threatening Randy Credico

- Alex Van der Zwaan, for lying to the FBI about Gates’ ongoing ties to Russian intelligence officer Konstantin Kilimnik

- Richard Pinedo, for stealing the identities of other Americans and selling them, including to Russian trolls

- A bunch of GRU officers, for hacking the DNC and other targets

- A bunch of paid trolls, for stealing the identities of American people and hiding their own true identity while paying for trolling infrastructure

The single indictment that Mueller brought that was a hyperextension of criminal law was against Yevgeniy Prigozhin, his trolls, his troll farm, and his shell companies for engaging in political activities in the US without registering; the theory of the case evolved over time to include getting unsuspecting Americans to engage in politics on behalf of foreign actors. Those are the charges that DOJ dropped (and I defended the decision, even though Barr’s rant makes me think questions about politicization may have merit). My suspicion is that Mueller charged it, in part, to be able to incorporate Prigozhin (and by extension, Vladimir Putin) into the indictment. But it was a stretch. Just what Barr says: a legal theory crafted — probably in part to establish a precedent for future tampering using social media — to go after a bad person, Prigozhin. The two subsequent complaints against Prigozhin’s trolls have not included the FARA charge.

But if Barr is speaking about Prigozhin, here, it raises real questions about why Interpol dropped the Red Notice against Prigozhin. Did Barr drop that request?

There’s one more investigation into foreigners helping Trump that Barr seems to be defending. Barr’s complaint that people in Mueller’s office wrote briefs for the Supreme Court also seems to suggest Barr disapproves of the Mystery Appellant case, which is understood to involve a bribe. That was the only case argued to the Supreme Court.

Mueller won that legal fight, even if the mystery foreign company who challenged a subpoena effectively avoided complying by lying anyway.

But by invoking Dreeben — one of the most respected Appellate lawyers in the country — Barr seems to be complaining that Trump might be investigated for accepting a bribe.

The Parallel Tracks of Disclosure on Why Manafort Shared Campaign Polling Data with His Russian Co-Conspirator

/78 Comments/in 2016 Presidential Election, Mueller Probe /by emptywheelNo one knows what the first half of this sentence says:

[redacted] the investigation did not establish that members of the Trump Campaign conspired or coordinated with the Russian government in its election interference activities.

But it almost certainly includes language acknowledging evidence that might support (but ultimately was not enough to indict on) a conspiracy charge.

I have twice before demonstrated that the Barr Memo — and so this full sentence — is nowhere near as conclusive with respect to exonerating Trump as a number of people have claimed (and Trump’s equivocations about releasing the report). This post showed how little Barr’s Memo actually incorporates from the Mueller Report. And this post shows that the memo ignores Stone’s coordination with WikiLeaks, presumably because he didn’t coordinate directly with the Russian government.

But (as I’ve said elsewhere), the public record on Paul Manafort’s conduct also makes it clear that the Mueller Report includes inconclusive information on whether the Trump campaign conspired with Russians. This came up extensively, in the discussion of Manafort’s sharing of polling data at his August 2, 2016 meeting with Konstantin Kilimnik, at the February 4 breach hearing.

At the beginning of that discussion, ABJ asked whether Manafort had lied to the grand jury about his motives for sharing polling data. [Throughout this, I’m bolding the redactions but including the content where it’s obvious.]

JUDGE AMY BERMAN JACKSON: I think we can go on to the question of the [redacted; sharing of polling data]. And I don’t have that many questions, mainly because I think it’s pretty straightforward what you’re saying.

So, I would want to ask you whether it’s part of your contention that he lied about the reason [redacted; he shared the data]. I know initially he didn’t even agree that that [redacted; he had shared private polling data], and he didn’t even really agree in the grand jury. He said it just was public information. But, I think there’s some suggestion, at least in the 302, as to what the point was of [redacted].

And so, I’m asking you whether that’s part of this, if he was lying about that?

Because Mueller’s team only needed ABJ to rule that Manafort lied, Andrew Weissmann explained they didn’t need her to reach the issue of motive. But they did discuss motive. Weissmann describes that it wasn’t just for whatever benefit sharing the polling data might provide the campaign, but it would also help Manafort line up his next gig and (probably) get out of debt to Deripaska.

MR. WEISSMANN: So, I don’t think the Court needs to reach that issue, and I don’t know that we’ve presented evidence on the — that issue.

THE COURT: You didn’t. So you just don’t want me to think about it, that’s okay.

MR. WEISSMANN: No. No. No. I’m going to answer your question.

THE COURT: All right.

MR. [WEISSMANN]: I’m just trying to, first, deal with what’s in the record. And I think that in the grand jury, Mr. Manafort said that from his perspective, [redacted], which he admitted at that point was with — he understood that it was going to be given by [redacted] to the [redacted; Ukrainian Oligarchs] and to Mr. [redacted; possibly Deripaska], both. That from his perspective, it was — there was no downside — I’m paraphrasing — it was sort of a win-win. That there was nothing — there was no negatives.

And I think the Government agrees with that, that that was — and, again, you’re just asking for our — if we are theorizing, based on what we presented to you, that we agree that that was a correct assessment.

But, again, for purposes of what’s before you on this issue, what his ultimate motive was on what he thought was going to be [redacted] I don’t think is before you as one of the lies that we’re saying that he told.

It’s more that what he specifically said was, he denied that he had told Mr. Gates [redacted; to bring the polling data to the meeting]. That he would not, in fact, have [redacted] and that he left it to [redacted].

Weissmann then goes on to allege that Manafort lied about sharing this polling data because if he didn’t, it would ruin his chance of getting a pardon.

And our view is, that is a lie. That that is really under — he knew what the Gates 302s were. It’s obviously an extremely sensitive issue. And the motive, I think, is plain from the [redacted], is we can see — we actually have — we can see what it is that he would be worried about, which is that the reaction to the idea that [long redaction] would have, I think, negative consequences in terms of the other motive that Mr. Manafort could have, which is to at least augment his chances for a pardon.

And the proof with respect to that is not just Mr. Gates. So that I will say there’s no contrary evidence to Mr. Gates, but you don’t have just Mr. Gates’s information. You have a series of emails where we know that Mr. Kilimnik, in fact, is reporting [redacted]

And probably the best piece of evidence is you have Mr. Manafort asking Mr. Gates to [redacted; print out polling data]. So, it’s — there’s — from three weeks ago, saying: [redacted].

In an effort to understand why this lie was important, ABJ returns to Manafort’s motive again, which leads Weissmann to point out that the question of why Manafort shared the polling data goes to the core of their inquiry.

THE COURT: I understand why it’s false. And I’m not sure I understand what you said at the beginning, that you — and I understand why you’ve posited that he might not want to be open about this, given the public scrutiny that foreign contacts were under at the time. But, I’m not sure I understand what you’re saying where you say you agree with him when he said it had no downside.

So, this is an important falsehood because it was false? Or is there some larger reason why this is important?

MR. WEISSMANN: So — so, first, in terms of the what it is that the special counsel is tasked with doing, as the Court knows from having that case litigated before you, is that there are different aspects to what we have to look at, and one is Russian efforts to interfere with the election, and the other is contacts, witting or unwitting, by Americans with Russia, and then whether there was — those contacts were more intentional or not. And for us, the issue of [redacted] is in the core of what it is that the special counsel is supposed to be investigating.

My answer, with respect to the Court’s question about what it is — what the defendant’s intent was in terms of what he thought [redacted] I was just trying to answer that question, even though that’s not one of the bases for saying there was a lie here. And so I was just trying to answer that question.

And what I meant by his statement that there’s no downside, is that can you imagine multiple reasons for redacted; sharing polling data]. And I think the only downside —

Weissmann ultimately explains that there was no downside to Manafort to sharing the polling data during the campaign, but there was a downside (angering Trump and therefore losing any hope of a pardon) to the information coming out now.

THE COURT: You meant no downside to him?

MR. WEISSMANN: Yes.

THE COURT: You weren’t suggesting that there was nothing — there’s no scenario under which this could be a bad thing?

MR. WEISSMANN: Oh, sorry. Yes. I meant there was no downside — Mr. Manafort had said there was no downside to Mr. Manafort doing it.

THE COURT: That was where I got confused.

MR. WEISSMANN: Sorry.

THE COURT: All right.

MR. WEISSMANN: And meaning all of this is a benefit. The negative, as I said, was it coming out that he did this.

In her breach ruling, ABJ agreed that Manafort’s sharing of polling data was a key question in Mueller’s inquiry, as it was an intentional link to Russia. She establishes this by noting that Manafort knew the polling data would be shared with someone in Russia (probably Deripaska; though note, this is where ABJ gets the nationality of the two Ukranian oligarchs wrong, which Mueller subsequently corrected her on).

Also, the evidence indicates that it was understood that [redacted] would be [redacted] from Kilimnik [redacted] including [redacted], and [redacted]. Whether Kilimnik is tied to Russian intelligence or he’s not, I think the specific representation by the Office of Special Counsel was that he had been, quote, assessed by the FBI, quote, to have a relationship with Russian intelligence, close quote. Whether that’s true, I have not been provided with the evidence that I would need to decide, nor do I have to decide because it’s outside the scope of this hearing. And whether it’s true or not, one cannot quibble about the materiality of this meeting.

In other words, I disagree with the defendant’s statement in docket 503, filed in connection with the dispute over the redactions, that, quote, the Office of Special Counsel’s explanation as to why Mr. Manafort’s alleged false statements are important and material turns on the claim that he is understood by the FBI to have a relationship with Russian intelligence.

I don’t think that’s a fair characterization of what was said. The intelligence reference was just one factor in a series of factors the prosecutor listed. And the language of the appointment order, “any links,” is sufficiently broad to get over the relatively low hurdle of materiality in this instance, and to make the [redacted] Kilimnik and [redacted] material to the FBI’s inquiry, no matter what his particular relationship was on that date.

Elsewhere, in discussing Manafort’s efforts to downplay Kilimnik’s role in his own witness tampering, ABJ refers to Kilimnik as Manafort’s “Russian conspirator.”

Earlier in the hearing ABJ notes that Manafort’s excuse for why he forgot details of the August 2 meeting only reinforce the likelihood that he shared the polling data to benefit the campaign.

You can’t say you didn’t remember that because your focus at the time was on the campaign. That relates to the campaign. And he wasn’t too busy to arrange and attend the meeting and to send Gates [redacted] that very day. It’s problematic no matter how you look at it.

If he was, as he told me, so single-mindedly focused on the campaign, then the meeting he took time to attend and had [redacted] had a purpose [redacted; to benefit the campaign]. Or, if it was just part of his effort to [redacted; line up the next job], well, in that case he’s not being straight with me about how single-minded he was. It’s not good either way.

She further notes that Manafort took this meeting with his Russian partner in Ukrainian influence peddling even though he was already under press scrutiny for those Ukrainian ties.

[T]he participants made it a point of leaving separate because of the media attention focused at that very time on Manafort’ relationships with Ukraine.

Her ruling also explains at length why sharing polling data would be useful to Kilimnik, citing from Rick Gates’ 302s at length.

In other words, these two filings — to say nothing of the backup provided in the January 15 submission, which includes all but one of Gates’ 302s describing the sharing of the polling data — lay out in some detail the evidence that Manafort clandestinely met with Konstantin Kilimnik on August 2, 2016, in part to share polling data he knew would be passed on to at least one other Russian, probably Deripaska.

And here’s why that’s interesting.

Back in early March, the WaPo moved to liberate all the documents about Manafort’s breach determination. On March 19, Mueller attorneys Adam Jed and Michael Dreeben asked for an extension to April 1, citing the “press of other work.”

The government respectfully requests an extension of time—through and including April 1, 2019—to respond to the motion. The counsel responsible for preparing the response face the press of other work and require additional time to consult within the government.

Three days later, Mueller announced he was done, and submitted his report to Barr. Then, on March 25, all of Mueller’s attorneys withdrew from Manafort’s case, which they haven’t done in other cases (the main pending cases are Mike Flynn, Concord Management, and Roger Stone). Then, on March 27, Mueller and Jonathan Kravis, the AUSA taking over a bunch of Mueller’s cases, asked for another extension, specifically citing the hand-off to Kravis and two others in the DC US Attorney’s Office.

The government respectfully requests a further two-week extension of time—to and including April 15, 2019—to respond to the motion. The Special Counsel’s Office has been primarily handling this matter. On March 22, the Special Counsel announced the end of his investigation and submitted a report to the Attorney General. This matter is being fully transitioned to the U.S. Attorney’s Office. Because of this transition, additional time will be required to prepare a response.

On March 29, Barr wrote the Judiciary Leadership and told them he’d release his redacted version of the Mueller report — which he’ll be redacting with the Mueller’s team — by mid-April, so around April 15.

So there are currently two parallel efforts considering whether to liberate the details of Manafort’s sharing of polling data with Kilimnik and through him Russia:

- The Barr-led effort to declassify a report that Mueller says does not exonerate Trump for obstruction, including the floating of a pardon to Manafort that (in Weissmann’s opinion) led Manafort to lie that and why he shared Trump campaign polling data to be passed on to Russians, which will be done around April 15

- The DC USAO-led effort to unseal the materials on Manafort’s lies, for which there is a status report due on April 15

Kevin Downing — the Manafort lawyer whose primary focus has been on preserving Manafort’s bid for a pardon — already expressed some concern about how the breach documents would be unsealed, to which ABJ sort of punted (while suggesting that she’d entertain precise the press request now before her.

MR. DOWNING: Your Honor, just one other general question: How are we going to handle the process of unredacted down the road? I mean, there’s been a lot of redactions in this case, and the law enforcement basis for it or ongoing grand jury investigations. What is going to be the process to — is the Office of Special Counsel going to notify the Court that the reason stated for a particular redaction no longer exists, or still survives? Is it going to be some sort of process that we can put in place?

THE COURT: Well, in one case, I know with all the search warrants, it was an evolving process. There were things that were withheld from you and then you got them but they were still withheld from the press and then the press got them. But usually things have to be triggered by a motion or request by someone. There may be reasons related to the defense for everything to stay the way it is.

I, right now, without knowing with any particularity what it is that you’re concerned about, or if — and not having the press having filed anything today, asking for anything, I don’t know how to answer that question. But I think that is something that comes up in many cases, cases that were sealed get unsealed later. And if there’s something that you think should be a part of the public record that was sealed and there’s no longer any utility for it, obviously you could first find out if it’s a joint motion and, if not, then you file a motion.

But for now, the prosecutors in DC will be in charge of deciding how much of the information — information that Barr might be trying to suppress, not least because it’s the clearest known evidence how a floated pardon prevented Mueller from fully discovering whether Trump’s campaign conspired with Russia — will come out in more detail via other means.

Update: And now, over a month after Mueller’s correction, three weeks after sentencing, and a week after the entire Mueller team moved on, Manafort submitted his motion for reconsideration from Marc. They’re still fighting about redactions.

As I disclosed last July, I provided information to the FBI on issues related to the Mueller investigation, so I’m going to include disclosure statements on Mueller investigation posts from here on out. I will include the disclosure whether or not the stuff I shared with the FBI pertains to the subject of the post.

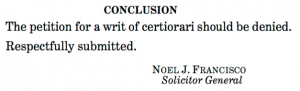

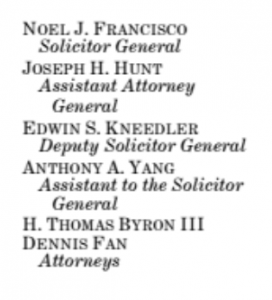

Yesterday Noel Francisco Raised the Stakes on the Mystery Appellant

/92 Comments/in 2016 Presidential Election, Mueller Probe /by emptywheelBack when President Trump fired Jeff Sessions, there was a CNN report describing how two competing groups of people discussed what to do in response. It described that Solicitor General Noel Francisco was in the Sessions huddle, a huddle focused, in part, on how to protect the Mueller investigation.

Eventually, there were two huddles in separate offices. Among those in Sessions’ office was Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein, his deputy Ed O’Callaghan, Solicitor General Noel Francisco and Steven Engel, who heads the Office of Legal Counsel.

[snip]

The fact that Whitaker would become acting attorney general, passing over Rosenstein suddenly raised concerns about the impact on the most high-profile investigation in the Justice Department, the Russia probe led by Mueller.

The Mueller probe has been at the center of Trump’s ire directed at Sessions and the Justice Department. Whitaker has made comments criticizing Mueller’s investigation and Rosenstein’s oversight of it, and has questioned the allegations of Russian interference.

Rosenstein and O’Callaghan, the highest-ranked officials handling day-to-day oversight of Mueller’s investigation, urged Sessions to delay the effective date of his resignation.

Francisco’s presence in the Sessions/Rosenstein huddle was significant for a number of reasons: If Rosenstein had been fired while Big Dick Toilet Salesman was Acting Attorney General, he would be the next superior officer, confirmed by the Senate, in the chain of command reviewing Mueller’s activities. As Michael Dreeben testified in the days after the firing, Francisco would have (and has had) to approve any appeals taken by Mueller’s team. In addition, it was significant that someone who is pretty fucking conservative was huddling with those who were trying to protect the investigation.

That’s why I’m interested in several details from the Mueller response to the Mystery Appellant challenge to a Muller subpoena submitted to SCOTUS yesterday.

First, as I expected, the government strongly rebuts Mystery Appellant’s claim that they are a foreign government (which was the spin in their own brief). Rather they are a commercial enterprise that a foreign government owns.

As the petition acknowledges (Pet. 1 n.1), petitioner is not itself a foreign government, but is a separate commercial enterprise that a foreign government owns.

That makes a ton of difference to the analysis, because the government has a much greater leeway in regulating businesses in this country than it does foreign governments.

Indeed, in one of the key parts of the brief, the government lays out the import of that: because if foreign owned companies were immune from subpoena, then on top of whatever problems it would create for regulating the foreign-owned corporation, it would also mean American citizens could deliberately use those foreign-owned corporations to shield their own criminal behavior.

Petitioner’s interpretation would, as the court of appeals recognized, lead to a result that Congress could not have intended—i.e., that “purely commercial enterprise[s] operating within the United States,” if majority- owned by a foreign government, could “flagrantly violate criminal laws” and ignore criminal process, no matter how domestic the conduct or egregious the violation. Supp. App. 10a. Banks, airlines, software companies, and similar commercial businesses could wittingly or unwittingly provide a haven for criminal activity and would be shielded against providing evidence even of domestic criminal conduct by U.S. citizens. See id. at 10a-11a. Although petitioner declares that result to be “precisely what Congress intended,” Pet. 25, it cannot plausibly be maintained that Congress and the Executive Branch—which drafted the FSIA—would have adopted such a rule “without so much as a whisper” to that effect in the Act’s extensive legislative history, Samantar, 560 U.S. at 319.8

In an unbelievably pregnant footnote to that passage, the government then notes that Mystery Appellant’s suggestion that the President could retaliate if foreign-owned corporations engaged in crime via something like sanctions ignores what tools are available if foreign-owned corporations don’t themselves engage in crime, but instead serve as a shield for the criminal activity of US citizens.

8 Petitioner suggests (Pet. 26) that Congress would not have been troubled by barring federal criminal jurisdiction over foreign state-owned enterprises because the President could use tools such as economic sanctions to address foreign instrumentalities “that commit crimes in the United States.” That overlooks not only the legal and practical limits on sanctions, but also the threshold need to acquire evidence through grand jury subpoenas in order to determine whether a crime has been committed—including by U.S. citizens.

Consider: There is significant evidence to believe that a foreign country — Russia — bribed Trump to give them sanctions relief by floating a $300 million business deal. There is also evidence that, after a series of back channel meetings we know Zainab Ahmed was investigating, such funds may have come through a Middle Eastern proxy, like Qatar. There is not just evidence that Qatar did provide funds no one in their right mind would have provided to the President’s family, in the form of a bailout to Jared Kushner’s albatross investment in 666 Fifth Avenue. But they’re already laying the groundwork to claim they accidentally bailed him out, without realizing what they were doing.

So if Russia paid off a bribe to Trump via Qatar, and Qatar is trying to hide that fact by claiming Qatar Investment Authority is a foreign government that can only be regulated in this country by sanctions imposed by the guy who is trading sanctions to get rich … well, you can see why that’s a non-starter.

Finally — going back to why I’m so interested that Francisco was in the Sessions/Rosenstein huddle — just Francisco’s name is on the brief, even though Dreeben and Scott Meisler surely had a role in drafting it.

This was noted to me by Chimene Keitner, who is an actual expert in all this (and did her own very interesting thread on the response).