Threshold issues

The very last thing Judge Michael Nachmanoff asked Michael Dreeben in Wednesday’s hearing on Jim Comey’s bid to throw out his indictment for vindictive prosecution, before turning to prosecutors’ argument, was whether he should wait and address all of Comey’s challenges at once or deal with vindictive prosecution on its own.

THE COURT: All right. Thank you. But before you sit down, let me just ask you, do you think that the other pending motions, including the issue of literal truth and ambiguity and the other matters that are yet to be litigated, are so wrapped up in vindictive prosecution that the Court should deal with them all at one time, or do you think that the Court can and should deal with vindictive prosecution separately?

MR. DREEBEN: I think vindictive prosecution, like our motion based on the appointment of the U.S. attorney, are threshold matters that the Court should resolve as a threshold. Mr. Comey would like to see both of those motions resolved because they both go to the very heart of whether a prosecution in this case is permissible, one by virtue of a challenge to the official who brought it, the other by virtue of whether it complies with the Constitution to bring a prosecution at all.

Our other motions are very important, and we have a series of them that challenge other aspects of the prosecution. As I’m sure the Court is well aware, there are issues relating to the conduct of the prosecutor in the grand jury. But this one and the appointments issue stand at the threshold. They’re the gateway to all further motions, and those should be resolved at the outset of the case, in our view.

Dreeben, calling vindictive prosecution and disqualification (which Judge Cameron Currie had heard the week before) “threshold” matters, said they should be decided at the outset.

That may explain Nachmanoff’s decision at the very end of the hearing to deny Jessica Carmichael’s request to move up the next motions hearing — the one that would address the other issues Nachmanoff asked Dreeben about — from December 9, what would be almost three weeks (including the Thanksgiving holiday) from that day, to the prior week.

There’s also a motion to move up the next oral argument, which is set on December 9th. I commend everyone’s enthusiasm for trying to move this even faster, but the Court is reluctant to do that. I believe that it was Ms. Carmichael that had a conflict, and I will permit counsel to appear without Ms. Carmichael, who’s local counsel, so that she doesn’t have that issue, but I will keep the current schedule that we have.

If Nachmanoff does treat the vindictive prosecution challenge as a threshold issue, then he may hope to rule before holding another hearing. If Nachmanoff were to rule for Comey on vindictive prosecution (or Currie were to disqualify Lindsey Halligan, as is likely), the December hearing might be delayed anyway during an appeal, possibly all the way to SCOTUS.

It’s worth noting that Comey’s appellate lawyers — Ephraim McDowell in the disqualification hearing and Dreeben in the vindictive prosecution one — argued these District level motions hearings. As I noted when they were added, Comey walked into these challenges preparing to fight this all the way to SCOTUS.

The Comey prosecution may go away, pending appeal, in less than 20 days, via one of at least two ways. Indeed, given Judge Currie’s promise to rule before Thanksgiving, it could go away in the next week (again, pending appeal).

I lay that out as a way to understand some other things that have happened since Nachmanoff’s hearing.

The drama

But first, the drama, which started shortly after Dreeben answered that question about threshold issues.

Loaner AUSA Tyler Lemons had barely started his argument when Nachmanoff questioned the prosecutor’s claim that the grand jury, “returned a true bill.”

THE COURT: Well, we’ll have some questions about that —

MR. LEMONS: That’s correct, Your Honor.

THE COURT: — but I’ll let you get through your argument.

Shortly thereafter, Nachmanoff challenged Lemons’ claim that Comey was relying on, “newspaper articles, anonymous sources, innuendo, [and] conjecture.”

THE COURT: Well, let me stop you there. With regard to the words of the president, whether it’s the post from September 20th or his answers to questions from reporters, you’re not suggesting that those aren’t things the president has said, are you?

Immediately before the drama of the declination memo, Nachmanoff bristled at Lemons’ insinuation that Erik Siebert, whom — the EDVA judge noted — had been appointed as US Attorney by the judges of EDVA, was involved in “machinations.”

MR. LEMONS: Absolutely, Your Honor. What I’m referring to is the newspaper reports that are relying on anonymous sources as to the machinations of former U.S. Attorney Siebert or to other decisions that essentially are not directly quoting the president or someone else.

THE COURT: Well, let me stop you there.

MR. LEMONS: Yes, sir.

THE COURT: I’m not sure what machinations you’re referring to. Are you referring to the fact that Mr. Siebert was the interim U.S. attorney and then appointed by the Court, and then either resigned on September 19th or was fired by the president on September 19th?

MR. LEMONS: Yes, Your Honor. And I guess more specifically referring to any sort of — across, it sounds like multiple cases, not just this case — any reluctance or willingness to pursue cases in this Court.

That’s when Nachmanoff spent several minutes slowly cornering Lemons into admitting, in spite of direction from Todd Blanche’s office to avoid doing so, that he did not just know of a declination memo, but had read it.

THE COURT: Well, was there a declination memo?

“Was there a declination memo?” was question one. Questions ten and eleven in the colloquy, which also included Nachmanoff reminding Lemons he was “counsel of record in this case” and then getting him to explain that Todd Blanche’s office had instructed him to dodge these questions, went this way:

THE COURT: And had one been prepared?

MR. LEMONS: My understanding is that a draft prosecution memo had been prepared.

THE COURT: All right. And did you review that?

MR. LEMONS: I — yes, Your Honor, I did.

That still wasn’t the most dramatic part of the hearing, of course.

Lemons finished his argument, and then Nachmanoff returned to that question, the grand jury presentment. From the start, he mentioned it would be useful to hear from Lindsey, but he did allow Lemons to explain what he thought had happened, first.

THE COURT: Well, I have a couple more questions before you sit down.

MR. LEMONS: Okay.

THE COURT: At the beginning of your remarks, you said that the grand jury had returned an indictment and there’s a presumption of regularity with what happened, but as we know from other litigation in this case, there have been some questions and some attempts to resolve those issues, and Ms. Halligan submitted a declaration on Friday that explained, in part, in response to the question from Judge Currie about what happened after the grand jury began to deliberate, and then what went on —

MR. LEMONS: Yes, Your Honor.

THE COURT: — after that. And I’ll ask you these questions, but it may be more direct to ask Ms. Halligan directly.

In spite of noting that it might be easier if Lindsey explained all this, Nachmanoff let Lemons explain what he understood had happened at length, including that the EDVA grand jury coordinator had had direct communications with the foreperson.

The judge asked Lemons the question about whether the full grand jury had voted on what he referred to as the second indictment three times, which is when he finally invited Lindsey to speak, as counsel of record. She barely said good morning before she interrupted the judge.

THE COURT: And so that the record is clear, when the grand jury return was taken, only the foreperson was in the courtroom, correct, the rest of the grand jurors were not present; is that right?

MR. LEMONS: Can I have a moment, Your Honor?

THE COURT: You can. Ms. Halligan, you can come to the podium. You’re counsel of record. You can address the Court. It might be easier. Good morning.

MS. HALLIGAN: Good morning.

THE COURT: So am I correct that, as is the usual —

MS. HALLIGAN: No, Your Honor.

THE COURT: — practice, that the grand jurors were not present, just the foreperson?

MS. HALLIGAN: The foreperson and another grand juror was also present, and Judge Vaala corrected the record in open court, and the foreperson said in open court, We only no true billed Count One, we want to true bill Count Two and Three, and the foreperson signed that indictment.

THE COURT: I’m familiar with the transcript.

MS. HALLIGAN: Okay.

THE COURT: But I just wanted to make sure that the entire grand jury never had the opportunity to see the second indictment. You may sit down. Thank you.

The government, of course, has now refuted this account, thinking it helps them to claim that Halligan (and Lemons) stood before the judge and misinformed him, all because a confused foreperson said that the entire grand jury had voted for the two-count indictment, which served primarily to corrode any presumption of regularity DOJ is afforded.

From the start (and so when he asked whether he should wait on the other challenges), Nachmanoff had at least those two questions, the grand jury and the declination memo, in mind, and also, probably, how Lindsey could have assessed the case in the three days before indicting.

THE COURT: Well, that’s why I was asking you the questions about the declination memo and the prosecution memo, because she was appointed on September 22nd, and she went into the grand jury on the 25th, and I believe what you’re saying is that she made an independent evaluation of the case and concluded to move forward with it in that time period, in those couple of days. And so my question is, what independent evaluation could she have done in that time period?

MR. LEMONS: Your Honor, I think that — that discussion is inevitably one that we would have if you order expanded discovery.

Michael Dreeben, in rebuttal, asserted that the irregularity with the indictment was obtained is yet another cause to dismiss the indictment, and asserted that Nachmanoff didn’t need to see what the declination memo said to dismiss it.

Nachmanoff closed the hearing not just by denying Carmichael’s request to advance the next motions hearing, but by ordering both parties to brief a case.

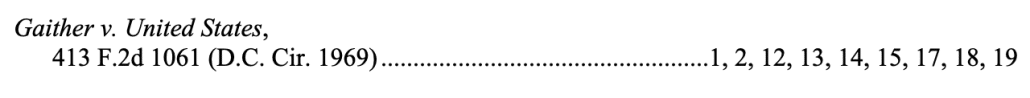

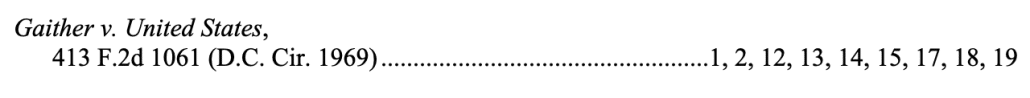

I have some housekeeping matters to address. I would like, especially in light of our argument today, both parties to address the case of Gaither v. United States, 413 F.2d 1061 (D.C. Cir. 1969), and it addresses this issue regarding the foreperson signing an indictment. And I know you have your objections due at 5:00 p.m. today, so I wanted to make sure the government was aware of the Court’s interest in addressing that case, and, of course, the defense can address it in turn when they file their response.

The oddities of a three-judge docket

Now, I’m going through this exercise not to share the drama from the transcript, much of which got covered in real time, but because I want to understand how the hearing on Wednesday — particularly Lindsey’s confession about the grand jury — jumbled what would have happened and will happen in the brief window before December 9, when some or all of this might be launched on its way to appeal, possibly all the way to SCOTUS.

Here’s what happened and will happen in the week since the hearing; I’ve color-coded response chains:

November 19: Vindictive prosecution hearing before Michael Nachmanoff; Nachmanoff denies motions schedule change, orders CIPA schedule, orders briefing on Gaither

November 19: Government objection to Fitzpatrick order giving Comey grand jury transcripts, writing up interactions between grand jury coordinator and grand jury foreperson and seemingly confirming that court reporter left after rest of grand jury left

November 19: Government brief on Gaither (responding to Nachmanoff’s order)

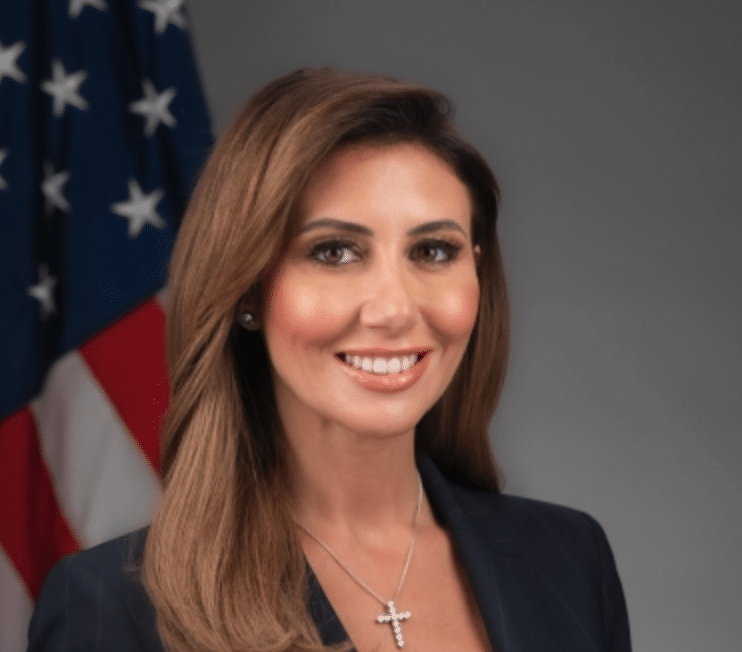

November 19: Insanely stupid Lindsey Halligan interview with NYPost misrepresenting record and attacking Judge Nachmanoff

November 20: Comey Reply on fundamental ambiguity

November 20: Comey Reply on Bill of Particulars (including exhibits on discovery, kicking off graymail)

November 20: Government notice “correcting” record, including return transcript

Later November 20: Comey Reply on his motion for grand jury materials

November 21: Consent motion to set CIPA hearing on December 9 instead of filing CIPA 5

November 21: Comey Response to government objection to Fitzpatrick order

November 21: Motion to dismiss because there is no indictment

November 21: Amended motion to dismiss because there is no indictment

November 24: Comey requested response date on MTD no indictment

November 26: Expected Cameron Currie ruling on disqualification

November 26: Comey motion to suppress due

Start from the end: with a motion to dismiss because there is no indictment, which Comey almost immediately amended. As the citations page makes clear, this is substantially Comey’s response to Nachmanoff’s request for briefing on Gaither.

As Comey explains in a footnote, rather than just responding to Gaither, he’s using belated disclosures — from the discovery about the Fourth Amendment and attorney-client violations, from William Fitzpatrick’s opinion on the grand jury transcript, and regarding the failure to present the second indictment — to submit a separate motion to dismiss to be considered along with the other ones.

Mr. Comey respectfully submits that the Court can and should consider this motion along with Mr. Comey’s other dispositive motions. ECF Nos. 59 [vindictive], 60 [disqualification], 105 [fundamental ambiguity]. Those motions are fully briefed, and the government has filed its notice concerning Gaither v. United States, 413 F.2d 1061 (D.C. Cir. 1969). See ECF No. 201. The defense requests that the Court direct the government to file its response to this Motion—if any—by November 24, 2025.

He is effectively attempting to squish this motion to dismiss into the window when Nachmanoff will be deciding the vindictive prosecution motion and Judge Cameron Currie will be deciding the disqualification motion, with the unrealistic request that the government have to respond over the weekend to also squish it into that same window.

Dreeben did say he was going to file another motion to dismiss and Nachmanoff did not object, but he’s trying to squish that motion into this window when the judges are deliberating.

The new motion to dismiss overlaps in significant part with two other filings submitted since the hearing: Comey’s reply on his request to get grand jury transcripts, and Comey’s response to the government’s objection to William Fitzpatrick’s order that he get those transcripts.

In his reply, Comey explains how all of these documents fit together.

1 The absence of a valid charging instrument will be the basis of a forthcoming motion to dismiss [that is, the Gaithner briefing as motion to dismiss].

2 As the Court is aware, Mr. Comey will file his response to the government’s appeal of Magistrate Judge Fitzpatrick’s order for the government to disclose the grand jury proceedings on Friday, November 21, 2025. This reply brief responds to the government’s arguments in opposition to the motion (ECF No. 184) to disclose the grand jury proceedings and highlights additional irregularities that have surfaced further warranting disclosure. Mr. Comey’s response to the government’s appeal of Magistrate Judge Fitzpatrick’s order will explain why Judge Fitzpatrick’s ruling is well supported by fact and law warranting affirmance and address the government’s opposition to that ruling. These litigation streams present two related, but separate, avenues to order the government to produce the grand jury proceedings.

And the seeming cause for amendment to the motion to dismiss — a replacement of one claim about how Lindsey Halligan integrated privileged material in the grand jury…

Ms. Halligan referred to those materials in her presentation to the grand jury and elicited extensive testimony about privileged materials from Agent-3. ECF No. 192 at 14.

With another…

In turn, Ms. Halligan extensively questioned Agent-3 about communications between Mr. Comey and Mr. Richman during Agent-3’s testimony before the grand jury. ECF No. 192 at 14.

… reveals one of the things going on. In all three documents, Comey aggressively accuses the government of purposely seeking out privileged material in advance of the presentment.

Agents knowingly reviewed and printed out dozens of pages of privileged communications between Mr. Comey and his lawyers and appear to have presented at least certain of those privileged communications to the grand jury in this matter.

Thus the delicate balance Comey tried to correct with the amendment: they’re pretty sure Miles Starr did not just present tainted testimony, but that Lindsey cued him with tainted questions, but that overstates what they can say without seeing the grand jury transcript.

Both those sentences must rely on this passage of Fitzpatrick’s opinion (they cite the unredacted version rather than this one; the redacted discussion starts on the next page).

The government’s position is that the grand jury materials “confirm the baselessness of the defendant’s claim that privileged information may have been shared with the grand jury.” ECF 172. While it is true that the undersigned did not immediately recognize any overtly privileged communications, it is equally true that the materials seized from the Richman Warrants were the cornerstone of the government’s grand jury presentation. The government substantially relied on statements involving Mr. Comey and Mr. Richman in support of its proposed indictment. Agent3 referred to these statements in response to multiple questions from the prosecutor and from grand jurors and did so shortly after being given a limited overview of privileged communications between the same parties. The government’s position that privileged materials were not directly shared with the grand jurors ignores the equally unacceptable prospect that privileged materials [page break] were used to shape the government’s presentation and therefore improperly inform the grand juror’s deliberations.

Both sides are working at a disadvantage in this argument. The government complained that it couldn’t see what Comey shared in ex parte submission to Fitzpatrick (and, generally, complained that it hadn’t been able to get its filter protocol).

2 Although the docket indicates the government provided the materials for in camera review, Dkt. No. 179, the docket does not reflect that defendant submitted ex parte information to the Magistrate Judge. However, the magistrate judge referenced the defendant’s ex parte notice in its opinion. See Dkt. 191 at 7.

In his response, Comey described some of what was included in that.

Pursuant to Judge Fitzpatrick’s order during the hearing, the defense filed an ex parte sealed submission to guide Judge Fitzpatrick’s review, which was supplemented with evidence that the government had produced to the defendant, such as the privileged communications the government’s agents printed out and used in September 2025 after their warrantless search of the materials seized from Daniel Richman.

[snip]

Mr. Comey plainly had an expectation of privacy in his communications with his lawyer, which was clear from the face of the communications the government agents reviewed and printed in September 2025, ECF No. 172-2 at 2,2 as set forth in the ex parte submission the defense submitted to Judge Fitzpatrick.

But unlike the government, Comey doesn’t know precisely what was said about the Richman texts to the grand jury, in particular whether Halligan’s promise of more evidence — a reference the government did no more than to confirm in its response by saying, “the government anticipated presenting additional evidence were the case to proceed to trial” — pertains specifically to the Comey side of the Richman texts.

Plus, both seem to be trying to hold their fire. Perhaps Comey is waiting on the motion to suppress — which may be held in abeyance if Judge Currie rules for him. Surely, he is guarding his privilege claim.

And, after admonishments from Fitzpatrick, the Loaner AUSAs dropped their reliance on the Richman texts in their Bill of Particulars response, so they’re probably trying to avoid knowing Fourth Amendment violations.

So neither will say what I keep saying: On the morning before the grand jury presentment, Spenser Warren provided others with a two page printout of Richman texts, all of which preceded the moment when the FBI knew Comey had retained Richman. But someone went back into that unscoped material they knew to include privileged texts and printed out at least eight pages of texts, going well beyond the time Comey had retained Richman.

And whatever the reason for the reticence on both sides, unless you are misrepresenting the questions at issue (and remember, there is no transcript of the exchange Comey had with Ted Cruz included among the 14 exhibits that appear to have been presented to the grand jury), there is no sound reason to present any of these texts. None could be proof that Comey had authorized Richman to share this information while at FBI, because Richman had left months earlier. None could be proof that Comey lied to Chuck Grassley on May 3, 2017 about serving as a source for stories on the Russian investigation (which Grassley called the Trump investigation), because they all postdated Grassley’s question. None could be proof that Comey intended to obscure all this in September 2020, because he had already told Susan Collins about all of this on June 8, 2017. Contrary to what Loaner AUSAs claimed in their urgent bill for a filter protocol (authored by James Hayes), nothing in the public record supports a claim that Comey and Richman (and Patrick Fitzgerald) were conspiring to leak classified information.

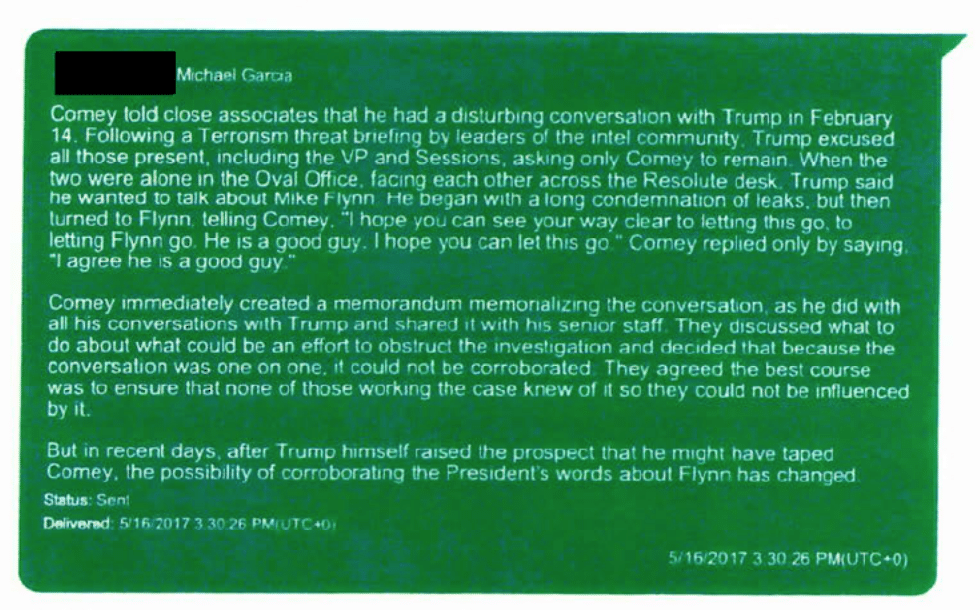

The only crime Comey committed was exposing Donald Trump’s corruption, which led to a Special Counsel investigation that showed abundant evidence Trump obstructed the investigation into his ties with Russia.

But in his effort to mislead a grand jury to believe that was a crime, Miles Starr may have knowingly and unlawfully surveilled attorney-client communications without a warrant much less a filter protocol.

As of now, Nachmanoff has not ruled on either parallel request to grant Comey grand jury access (he said he would rule on the filings, without a hearing), though a footnote to the motion to dismiss, “reserves the right to supplement this Motion with further facts and argument if and when the grand jury materials are disclosed to the defense.” So unless and until he does, the record will remain what it is, with vague gestures from both sides about a conflict at the heart of this case, potentially excluded from the record if this thing gets appealed.

When caught lying, troll

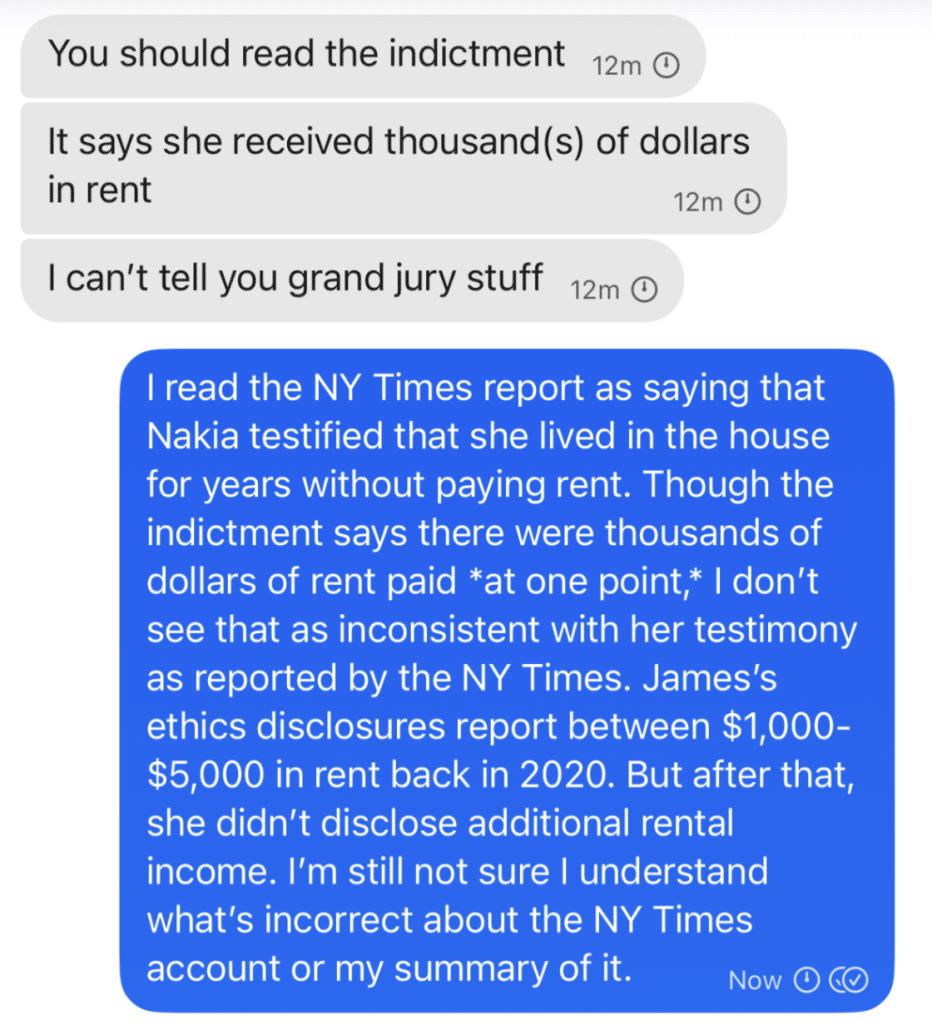

Meanwhile, of course, Lindsey Halligan is already resorting to the tactics she learned from her boss, falsely misrepresenting a question Nachmanoff posed about Dreeben’s belief, laid out in Comey’s reply to prosecutors’ arguments about imputation (which I laid out here)…

MR. DREEBEN: That is certainly correct, and that is an additional obstacle that supported the court’s factual conclusion that imputation was not appropriate on the facts of the case. But we, of course, have a very different situation. In the hierarchy, the president stands at the top, and he has declared himself to be the chief law enforcement officer of the United States. He has vested in him executive power, which includes supervision of the Department of Justice. The U.S. attorneys help him carry out his responsibility to see that the laws are faithfully executed, and as we argued in the brief, that is not just a theoretical constitutional structural argument; it is actually an argument that applies to the facts of this case because the president has taken on the responsibility and the authority to direct the Justice Department to take actions in the investigatory and prosecutorial realm that he thinks should be taken, and he has, in effect, substituted himself for the U.S. attorney as the decision-maker, and the facts of this case reveal that that’s why his vindictive motive is imputed to the prosecution. No, he didn’t go into the grand jury, but exercising the authority that’s vested in him, he brought about the prosecution through the chain of causation that we described earlier.

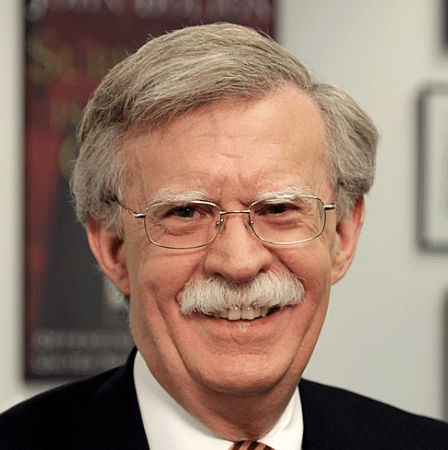

THE COURT: So your view is that Ms. Halligan is a stalking horse or a puppet, for want of a better word, doing the president’s bidding?

MR. DREEBEN: Well, I don’t want to use language about Ms. Halligan that suggests anything other than she did what she was told to do. The president of the United States has the authority to direct prosecutions. She worked in the White House. She was surely aware of the president’s directive. She didn’t have prosecutorial experience, but she took on the job to come to the U.S. Attorney’s Office and carry out the president’s directive, and this was a directive to the attorney general. I think we know that the attorney general is highly responsive to the president’s directives. She doesn’t say, Excuse me, Mr. President, this is my job.

The makebelieve US Attorney for EDVA instead falsely claimed this was a direct expression of Nachmanoff’s own opinion.

Interim US Attorney Lindsey Halligan suggested Wednesday that the Biden-appointed judge overseeing the criminal case against former FBI Director James Comey violated judicial conduct rules by asking if she was a “puppet” of President Trump.

District Judge Michael Nachmanoff asked Comey’s defense lawyer if he thought Halligan, the prosecutor who brought the indictment against the former FBI boss, was acting as a “puppet” or “stalking horse” of the commander in chief, during a hearing in an Alexandria, Va., courtroom.

“Personal attacks — like Judge Nachmanoff referring to me as a ‘puppet’ — don’t change the facts or the law,” Halligan exclusively told The Post.

“The Judicial Canons require judges to be ‘patient, dignified, respectful, and courteous to litigants, jurors, witnesses, lawyers, and others with whom the judge deals in an official capacity’ … and to ‘act at all times in a manner that promotes public confidence in the integrity and impartiality of the judiciary,’” she continued.

Lindsey’s attack in the NYP was similar to the one prosecutors made in their response to Fitzpatrick’s order (which Comey addressed in response).

Federal courts have an affirmative obligation to ensure that judicial findings accurately reflect the evidence. Canon 2(A) of the Code of Conduct for United States Judges requires every judge to “act at all times in a manner that promotes public confidence in the integrity and mpartiality of the judiciary” and to avoid orders that “misstate or distort the record.” Canon 3(A)(4) requires courts to ensure that factual determinations are based on the actual record, not assumptions or misrepresentations. Measured against these obligations and the rule of law, the magistrate’s reading of the transcript cannot stand.

They’re trolling.

They’re doing precisely what Trump always does when caught in a crime: he trolls and attacks rule of law.