Section 702 Reauthorization Bill: The Very Narrowly Scoped Back Door Search Fix

This is my second post on the draft House Judiciary Committee version of the Section 702 reauthorization. In this post, I’ll look at how the bill tries to fix the back door search loophole. In two followup posts I’ll explain why this fix is inadequate legislatively, and why it is inadequate legally.

The back door fix:

- Requires a court order to access content “for evidence of a crime”

- Requires an AG relevance statement to access metadata-plus

- Creates exceptions that swallow the rule

- Prevents reverse targeting

- Mandates simultaneous access to FBI databases

- Permits broad delegation

- Creates auditable records with big loopholes

- Invites the government to define foreign intelligence information

Requires a court order to access content “for evidence of a crime”

Here’s the language that requires the government to obtain a court order when accessing Section 702 data.

(j) REQUIREMENTS FOR ACCESS AND DISSEMINATION OF COLLECTIONS OF COMMUNICATIONS.—

(1) COURT ORDERS AND OTHER REQUIREMENTS.—

(A) COURT ORDERS TO ACCESS CONTENTS.—Except as provided by subparagraph (C), in response to a query for evidence of a crime, the contents of queried communications acquired under subsection (a) may be accessed or disseminated only upon—

(i) an application by the Attorney General to a judge of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court that describes the determination of the Attorney General that—

(I) there is probable cause to believe that such contents may provide evidence of a crime specified in section 2516 of title 18, United States Code (including crimes covered by paragraph (2) of such section);

(II) noncontents information accessed or disseminated pursuant to subparagraph (B) is not the sole basis for such probable cause;

(III) such queried communications are relevant to an authorized investigation or assessment, provided that such investigation or assessment is not conducted solely on the basis of activities protected by the first amendment to the Constitution of the United States; and

(IV) any use of such queried communications pursuant to section 706 will be carried out in accordance with such section;

(ii) an order of the judge approving such application.

The requirement only applies to evidence of crime. It requires the crime to be one of the ones listed in the Wiretap Act, but includes state crimes, which in turn includes drug crimes (and child pornography, which of course is now in Section 702’s minimization procedures).

For some reason, it requires this application to go to FISC, rather than a regular magistrate, which is problematic both from a time management issue for FISC but also for reasons of standardization among magistrates. That’s all the more concerning given that the bill doesn’t explain what kind of review the FISC judge can do — whether the judge can actually review for probable cause, or whether she doesn’t have that authority. This is a big concern, because DOJ has repeatedly told FISC judges in secret that they don’t have authority specifically laid out in law, not even when they were asking judges to approve programmatic spying.

One good part of this language is that it requires something beyond metadata from a 702 search to support a probable cause review.

As I’ll write in a follow-up, though, the limitation of this to criminal purposes makes it absolutely meaningless — it simply misunderstands how FBI conducts these queries (and obviously doesn’t apply to how NSA and CIA do it).

Requires an AG relevance statement to access metadata-plus

In addition to the controls on content, this reauthorization also imposes new controls on access to metadata-plus.

(B) RELEVANCE AND SUPERVISORY APPROVAL TO ACCESS NONCONTENTS INFORMATION.—Except as provided by subparagraph (C), in response to a query for evidence of a crime, the information of queried communications acquired under subsection (a) relating to the dialing, routing, addressing, signaling, or other similar noncontents information may be accessed or disseminated only upon a determination by the Attorney General that—

(i) such queried communications are relevant to an authorized investigation or assessment, provided that such investigation or assessment is not conducted solely on the basis of activities protected by the first amendment to the Constitution of the United States; and

(ii) any use of such queried communications pursuant to section 706 will be carried out in accordance with such section.

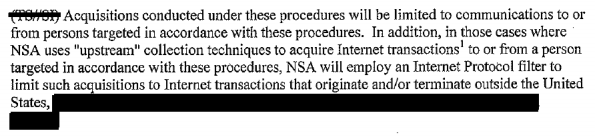

This imposes an Attorney General certification of relevance for access to 702-derived “metadata-plus.” I’m using that term to refer to the broadened definition of metadata that presumably invokes John Bates’ definition adopted in a series of opinions, but which remains entirely redacted.

Consider the absurdity of the proposition that the government can search “just metadata” but metadata is so sensitive it can’t be publicly defined. And Congress chooses not to define it here either.

If we need to revisit the definition of metadata, then Congress should do it here, not just nod blindly to redacted opinions at FISC.

And, again, this applies only to crimes.

Creates exceptions that swallow the rule

As I keep saying, the back door search fix only applies to criminal searches. Here’s what is not included.

(C) EXCEPTIONS.—The requirement for an order of a judge pursuant to subparagraph (A) and the requirement for a determination by the Attorney General under subparagraph (B), respectively, shall not apply to accessing or disseminating queried communications acquired under subsection (a) if one or more of the following conditions are met:

(i) Such query is reasonably designed for the primary purpose of returning foreign intelligence information.

(ii) The Attorney General makes the determination described in subparagraph (A)(i) and

(I) the person related to the queried term is the subject of an order or emergency authorization that authorizes electronic surveillance or physical search under this Act or title 18 United States Code; or

(II) the Attorney General has a reasonable belief that the life or safety of a person is threatened and such contents are sought for the purpose of assisting that person.

(iii) Pursuant to paragraph (5), the person related to the queried term consents to such access or dissemination.

First, the bill exempts emergency or threat to life queries.

But before it does that, it exempts all requests “designed for the primary purpose of returning foreign intelligence information.” In a different section, HJC punts on the issue of defining what “foreign intelligence information” means, directing the government to do that in minimization procedures.

It punts on more than that. How can you have one category for “primary purpose” FI information, but then not treat criminal searches as primary? Where does that line end? Especially given that this is permitted, for both criminal and intelligence purposes, at the assessment level, which is before the government has any evidence.

In short, even where it is writing exceptions, the bill does it in such a way as to let the split swallow the rule.

Prevents reverse targeting

I think this language prohibits reverse targeting.

(D) LIMITATION ON ELECTRONIC SURVEILLANCE OF UNITED STATES PERSONS.—If the Attorney General determines that it is necessary to conduct electronic surveillance on a known United States person who is related to a term used in a query of communications acquired under subsection (a), the Attorney General may only conduct such electronic surveillance using authority provided under other provisions of law.

As I read it, if the FBI queries 702 data and finds evidence of a crime, they cannot then develop that evidence using already collected (or newly targeted) 702 data. They have to get a criminal warrant to do it.

Mind you, this is the kind of authorities laundering they do anyway, but this prohibition is worthwhile.

Mandates simultaneous access to FBI databases

The most interesting — and potentially dangerous — language in this section mandates that when the FBI does queries, all the data they have be accessible.

(E) SIMULTANEOUS ACCESS OF FBI DATABASES.—The Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation shall ensure that all available investigative or intelligence databases of the Federal Bureau of Investigation are simultaneously accessed when the Bureau properly uses an information system of the Bureau to determine whether information exists in such a database. Regardless of any positive result that may be returned pursuant to such access, the requirements of this subsection shall apply.

I say it’s dangerous, because it might require very compartmented data to be more broadly accessible.

But the other thing that’s interesting about it is it will ensure that if there’s any multiplicitous data in the databases, FBI will have options to bypass the intent of the back door fix.

Consider: a great deal of individually targeted FISA data will replicate data obtained using 702 (which may in fact be the data the government used to obtain a targeted FISA order). A search on such data will return both the traditional FISA data and the 702 data. In cases where the FBI can use the former, they don’t have to bother with a “warrant” from FISC. As FBI obtains more and more raw EO 12333 data, that will be even more true there.

So while there may be an interesting operational reason for this — perhaps FBI even missed information in some sensitive investigation because not all data was accessible? — there are also clear downsides and the likelihood this will turn into a workaround to make the back door search even less meaningful.

Permits broad delegation

Another thing HJC doesn’t bother to specify is how broadly the Attorney General can delegate the authority for these various declarations.

(F) DELEGATION.—The Attorney General shall delegate the authority under this paragraph to the fewest number of officials that the Attorney General determines practicable.

(2) AUTHORIZED PURPOSES FOR QUERIES.—A collection of communications acquired under subsection (a) may only be queried for legitimate national security purposes or legitimate law enforcement purposes.

This was a significant problem behind the early NSL abuses. Letting the AG decide how much authority he wants to delegate invites similar abuses and is not why we’re paying Congress.

Creates auditable records with big loopholes

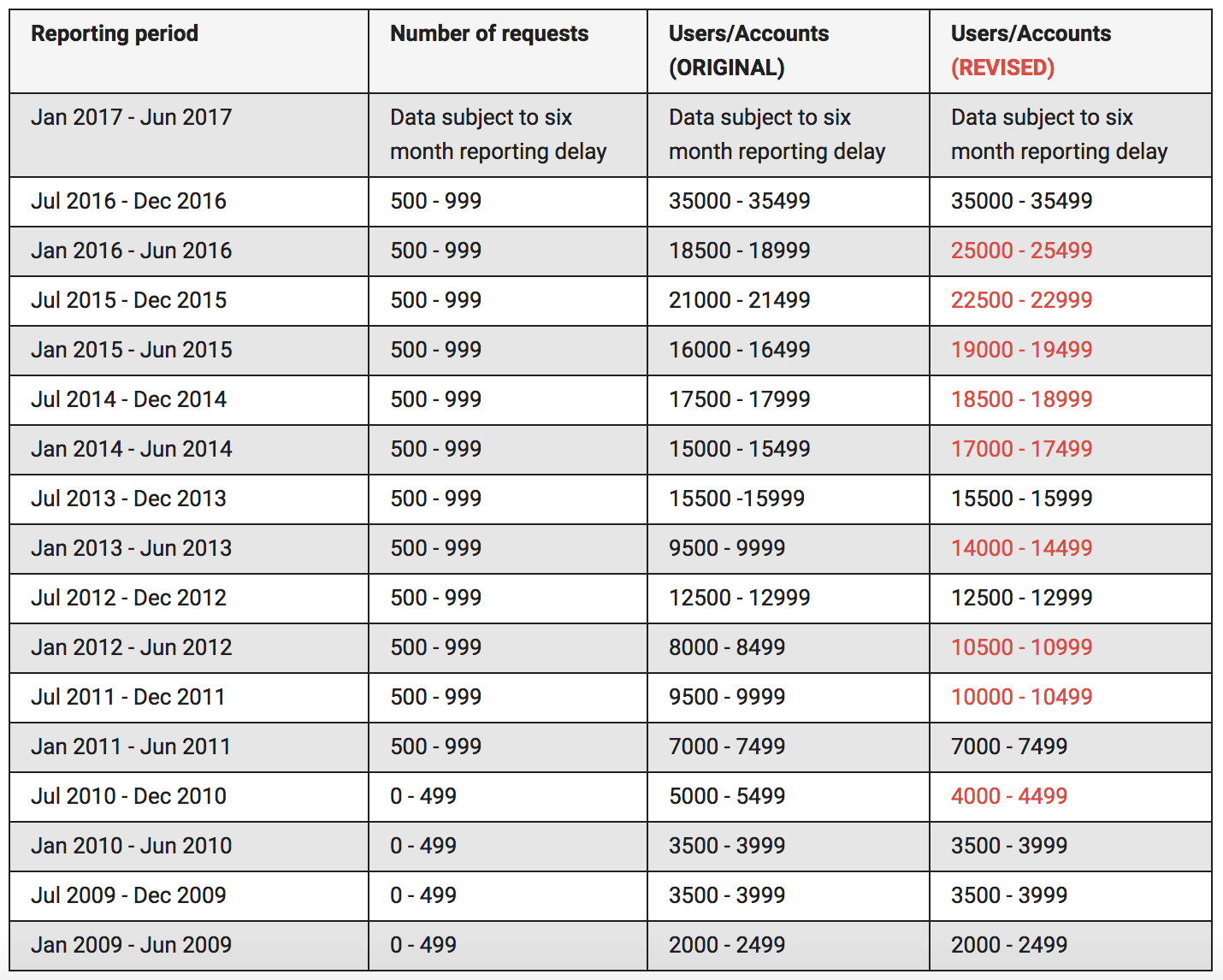

As always with transparency provisions, the loopholes are far more interesting than the provisions themselves, because they reveal where the interesting stuff is hiding. This requirement applies to all four agencies that get raw 702 traffic: NSA, CIA, NCTC, and FBI.

NSA is already doing this kind of record-keeping (sort of, though given the violations discovered last year, there’s reason to doubt it). But once they set the requirement, they create big problematic loopholes.

(3) RETENTION OF AUDITABLE RECORDS.— The Attorney General and each Director concerned shall retain records of queries that return a positive result from a collection of communications acquired under subsection (a). Such records shall—

(A) include such queries for not less than 5 years after the date on which the query is made; and

(B) be maintained in a manner that is auditable and available for congressional oversight.

With this language, HJC exempts Congressional queries (which I’m fine with), but also tech queries.

(4) COMPLIANCE AND MAINTENANCE.—The requirements of this subsection do not apply with respect to queries made for the purpose of—

(A) submitting to Congress information required by this Act or otherwise ensuring compliance with the requirements of this section; or

(B) performing maintenance or testing of information systems.

Until at least 2010, NSA was using tech queries to do metadata searches that weren’t authorized by the phone dragnet (which was facilitated by having tech people co-located with analysts, which made it easy for the analysts to as for help). If you exempt tech people, you will have abuses on any restriction.

In addition, the auditable record requirement doesn’t count for those who’ve given consent, which includes informants.

(5) CONSENT.—The requirements of this subsection do not apply with respect to—

(A) queries made using a term relating to a person who consents to such queries; or

(B) the accessing or the dissemination of the contents of queried communications of a person who consents to such access or dissemination.

From this I assume that a great many of these queries (especially those at CIA that aren’t now being counted) are being done for Insider Threat detection, which tracks a bunch of people who, by obtaining a clearance, have given consent for this kind of searching. I assume there are a great many of them too, since they need to be hidden.

(6) DIRECTOR CONCERNED.—In this subsection, the term ‘Director concerned’ means the following:

(A) The Director of the National Security Agency, with respect to matters concerning the National Security Agency.

(B) The Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, with respect to matters concerning the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

(C) The Director of the Central Intelligence Agency, with respect to matters concerning the Central Intelligence Agency.

(D) The Director of the National Counterterrorism Center, with respect to matters concerning the National Counterterrorism Center.

Invites the government to define foreign intelligence information

Finally, the bill requires the government to adopt a meaning for “query reasonably designed for the primary purpose of returning foreign intelligence information” in yearly certifications, rather than doing it themselves.

(b) PROCEDURES.—Subsection (e) of such section 6 (50 U.S.C. 1881a(e)) is amended by adding at the end the following new paragraph:

(3) CERTAIN PROCEDURES FOR QUERYING.— The minimization procedures adopted in accordance with paragraph (1) shall describe a query reasonably designed for the primary purpose of returning foreign intelligence information pursuant to subsection (j)(1)(C)(i).’’.

Again, it is the job of Congress to do this. Once the IC defines this in such a way that will further swallow up the rule, what then? We wait until 2023 (which is when this law would next get reauthorized) to define the term meaningfully? At some point we need to have an explicit discussion about the foreign intelligence purposes that drive a lot of these queries, and talk about whether they’re permissible under the Fourth Amendment. Now would be a good time, but this language just punts the question.

Other 702 posts

702 Reauthorization Bill: The “About” Fix (What Is A Person?)

![[Photo: National Security Agency, Ft. Meade, MD via Wikimedia]](https://www.emptywheel.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/NationalSecurityAgency_HQ-FortMeadeMD_Wikimedia.jpg)