DOJ and Mike Flynn responded to Amicus John Gleeson’s filing arguing that Judge Emmet Sullivan should reject DOJ’s motion to dismiss Flynn’s prosecution today.

Sidney Powell claims Bill Priestap’s attempt to shield Flynn is misconduct

Sidney Powell’s brief was like all her other ones, legally a shit-show, at times making false claims, at others rolling out a word salad designed to impress the frothy right. It did not substantively address Gleeson’s filing but instead mostly repeated the arguments made in support of the petition for mandamus.

Two details are important, however. First, Powell repeatedly argued that both the FBI and DOJ’s prosecutors engaged in misconduct, in the latter case arguing the prosecutors withheld information covered by Brady.

Given the substantial briefing and documentation by the Justice Department of the reasons for dismissal here, based primarily on the Government’s proper recognition that it should correct its own misconduct which included suppression of extraordinary exculpatory evidence, this court has no further role to play than to grant dismissal forthwith. Smith, 55 F.3d at 159; United States v. Hamm, 659 F.2d 624, 631 (5th Cir. 1981).

[snip]

In its ninety-two-page decision denying General Flynn all exculpatory Brady material he requested, the court distinguished this case from United States v. Stevens, Criminal Action No. 08-231 (EGS) (D.D.C Apr. 1, 2009), because in Stevens, the government moved to dismiss the case upon admitting misconduct in the suppression of Brady evidence. ECF No. 144 at 91. That distinction is eviscerated with the Government’s Motion to Dismiss here. Moreover, in Stevens, the government filed a mere two-page motion to dismiss. Ex. 4. Here, the Government has moved to dismiss in a hundred-page submission that includes 86 pages of new documentation that completely destroys the premise for any criminal charges. This evidence was long sought by General Flynn but withheld by the prior prosecution team and its investigators and wrongly denied to him by this court.

[snip]

Amicus elides the reality of the egregious government misconduct of the FBI Agents—particularly that of Comey, McCabe, Strzok, Page, Pientka, Priestap and others who met repeatedly to pursue the targeted “take-out” of General Flynn for their political reasons and those of the “entirety lame duck usic.”

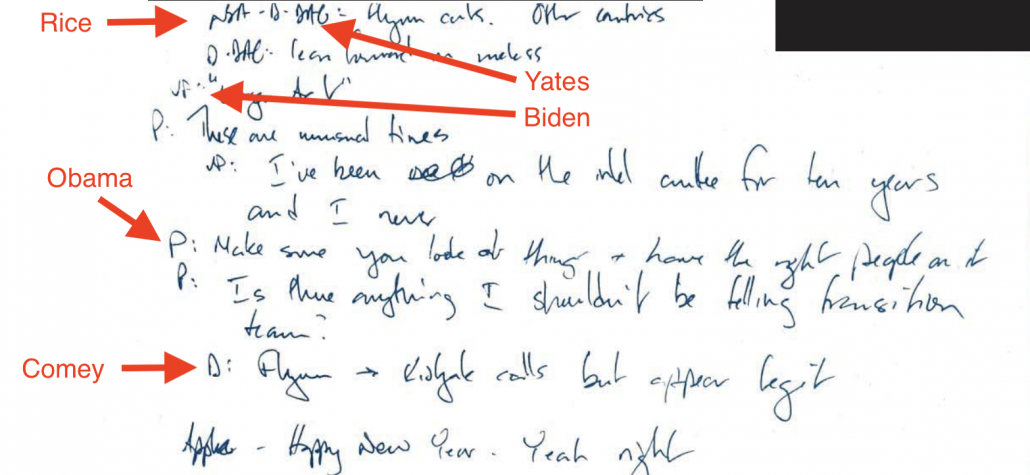

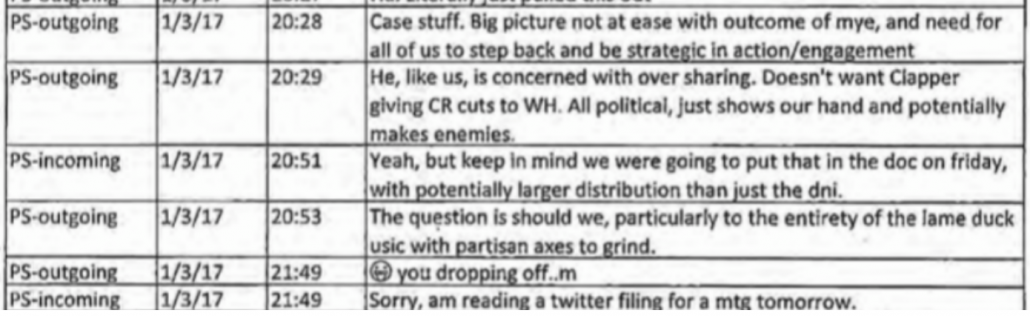

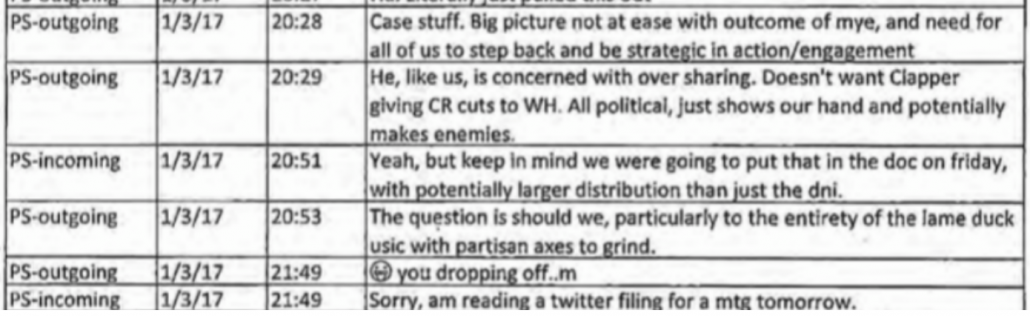

That last reference to the “entirely lame duck usic” refers to some text messages involving Strzok which, she claims, “the defense recently found that were never produced to it by the Government,” which given how the government provided the text messages probably means only that she didn’t look before. The text messages show Strzok describing a conversation with Bill Priestap about withholding the full transcripts of Flynn’s calls with Sergey Kislyak from the Obama White House to avoid having Obama dead-enders politicizing them — precisely the opposite of what her entire argument is premised on!!!.

So Powell’s new smoking gun–the thing she’s using to rile up the frothers–is proof that Strzok tried really hard to protect Flynn from precisely what she claims did him in, a politicized prosecution led by Obama people. In doing so, she presents evidence (and not for the first time) that Strzok tried really hard to protect Flynn.

Jocelyn Ballantine invents entirely new reasons why DOJ is moving to dismiss

The government’s response is the least-shitty argument DOJ has made in defense of abandoning Flynn’s prosecution, yet it still presents new problems for their case.

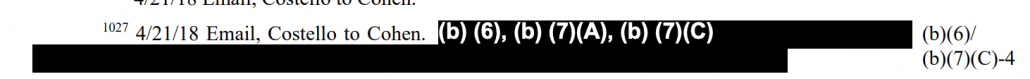

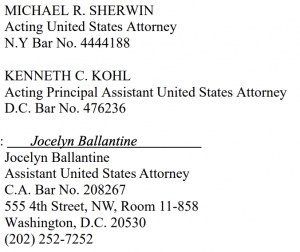

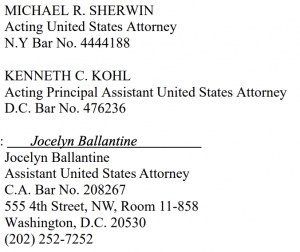

The government response was signed by a different team of people than have signed anything submitted thus far. Whereas only Timothy Shea — since promoted to be acting DEA Administrator — signed the initial motion to dismiss, and a team including five people from the Solicitor General’s office, including outgoing Solicitor General Noel Francisco himself, outgoing Criminal Division head Brian Benczkowski, in addition to people from the DC US Attorney’s office and career National Security Division prosecutor Jocelyn Ballantine signed the response on the DC Circuit petition for mandamus, this filing includes only the the latter three:

Whereas the Circuit filing necessarily argued a constitutional issue — the limits of a judge’s authority to deny a motion to dismiss the prosecution, this one argued an admittedly overlapping criminal one, one that makes the third different argument justifying the motion to dismiss. Significantly, this is a defense of the motion to dismiss that (unlike the original one) Jocelyn Ballantine, one of the two prosecutors on the case, was willing to sign.

Along the way, Ballantine presents new reasons to substantiate the claim that DOJ couldn’t convince a jury Flynn was guilty, including describing two things that she now claims weren’t in the notes but were in Flynn’s final 302.

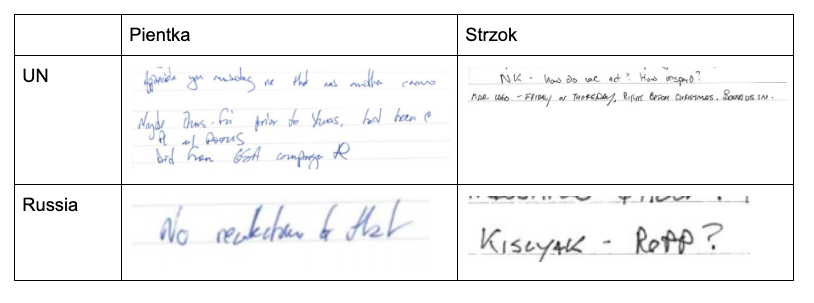

According to the final FD-302, when the agents asked Flynn whether he recalled any conversation with Kislyak in which he encouraged Kislyak not to “escalate the situation” in response to the sanctions, Flynn responded, “Not really. I don’t remember. It wasn’t, ‘Don’t do anything.’” Doc. 198-7, at 6. According to the FD-302, the agents asked Flynn whether he recalled a conversation in which Kislyak stated that Russia had taken the incoming administration’s position into account when responding to the sanctions; Flynn stated that he did not recall such a conversation. Id. The agents’ handwritten notes do not reflect that question being asked or Flynn’s response. See Doc. 198-13, at 2-8.

The final FD-302 also reports that Flynn incorrectly stated that, in earlier calls with Kislyak, Flynn had not made any request about voting on a UN Resolution in a certain manner or slowing down the vote. Doc. 198-7, at 5. Flynn indicated that the conversation, which took place on a day when he was calling many other countries, was “along the lines of where do you stand[ ] and what’s your position.” Id. The final FD-302 also states that Flynn was asked whether Kislyak described any Russian response to his request and said that Kislyak had not, id., although the agents’ handwritten notes do not reflect Flynn being asked that question or giving that response, see Doc. 198-13, at 2-8.

[snip]

The interview was not recorded and the final FD-302 includes two instances where the agents did not record a critical question and answer in their handwritten notes: (1) that agents asked Flynn whether he recalled a conversation in which Kislyak stated that Russia had taken the incoming administration’s position into account when responding to the sanctions, and Flynn stated that he did not recall such a conversation; and (2) that the agents asked whether Kislyak described any Russian response to his request, and Flynn said that Kislyak had not.

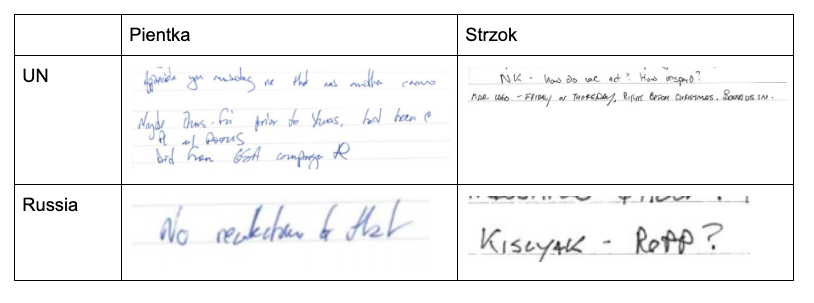

This is actually a claim Sidney Powell has made in the past, though I found notes consistent with those questions here, explicitly so with respect to the sanctions conversation:

[Update: Note that, as I first pointed out, the notes here are reversed; Strzok’s are the ones on the left, Pientka’s are the ones on the right.]

Ballantine herself was on a filing stating that, “The final interview report, just like the agent’s handwritten notes, reflect all of the above material false statements” (though that filing did not address whether Flynn was asked about Russia taking Trump’s stance into account; see especially page 5 for the extended discussion that lacks that). And Judge Sullivan agreed, ruling in December that,

Having carefully reviewed the interviewing FBI agents’ notes, the draft interview reports, the final version of the FD302, and the statements contained therein, the Court agrees with the government that those documents are “consistent and clear that [Mr. Flynn] made multiple false statements to the [FBI] agents about his communications with the Russian Ambassador on January 24, 2017.”

Ballantine–consistent with her past signed filing–does not contest that some of Flynn’s lies are clearly included in the notes, and so doesn’t contest that the notes clearly show Flynn lying at least twice to prosecutors.

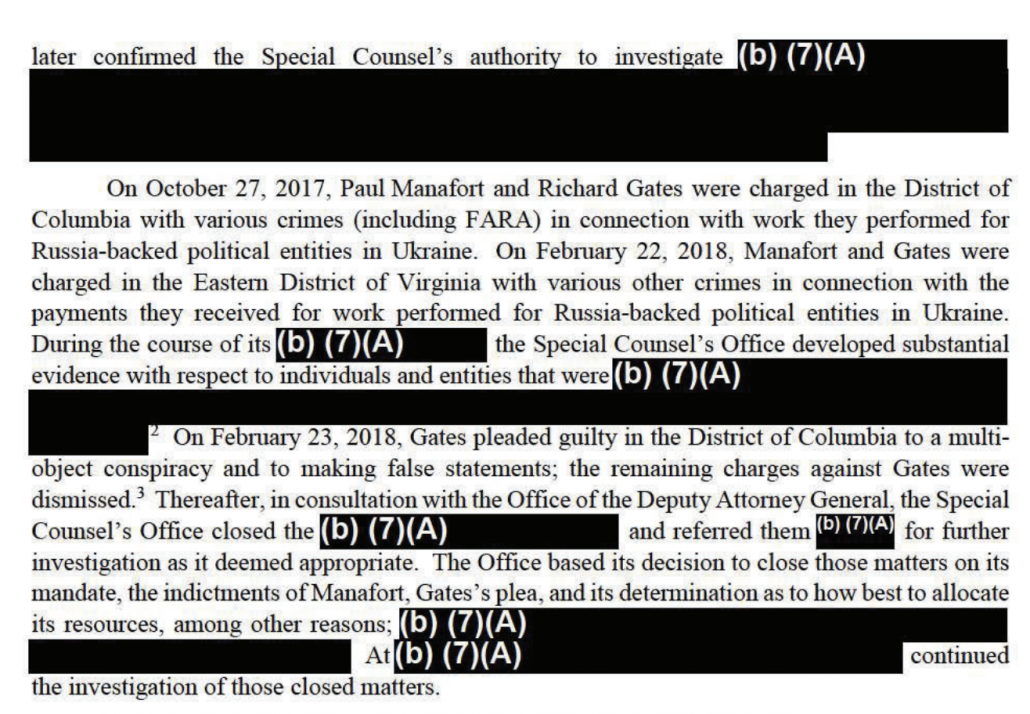

Ballantine also further develops the “new thing” that the motion to dismiss relied on to justify flip-flopping on past DOJ stances (though it is the same “new thing” presented in the Circuit filing): the new developments involving essential participants in Flynn’s prosecution:

Furthermore, since the time of the plea, extensive impeaching materials had emerged about key witnesses the government would need to prove its case. Strzok was fired from the FBI, in part because his text messages with Page revealed political bias against the current administration and “implie[d] a willingness to take official action to impact the presidential candidate’s electoral prospects.” U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Office of the Inspector General, A Review of Various Actions by the Federal Bureau of Investigation and Department of Justice in Advance of the 2016 Election xii (December 2018). The second interviewing agent has been accused of acting improperly in connection with the broader investigation. McCabe, who authorized Flynn’s interview without notifying either the Department of Justice or the White House Counsel, was fired for conduct that included lying to the FBI and lying under oath. U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Office of the Inspector General, A Report of Investigation of Certain Allegations Relating to Former FBI Deputy Director Andrew McCabe 2 (February 2018). In addition, significant witnesses have pending investigations or lawsuits against the Department of Justice, which could create further questions about their testimony at trial. See Strzok v. Barr, Civ. No. 19-2367 (D.D.C. Aug. 6, 2019); McCabe v. Barr, Civ. No. 19-2399 (D.D.C. Aug. 8, 2019); Page v. Dep’t of Justice, Civ. No. 19-3675 (D.D.C. Dec. 10, 2019). Those developments further support the government’s assessment about the difficulty it would have in proving its case to a jury beyond a reasonable doubt.

While this information would definitely make it harder (but in no way impossible, not least because there are witnesses like Mike Pence and KT McFarland to Flynn’s lies) to prove DOJ’s case, as Gleeson pointed out in his brief, DOJ didn’t have to do that — they already have two allocutions of guilt, including one that affirmed Flynn could never again raise such issues! Moreover, all but one of these new “new things” happened before Flynn reallocuted his guilty plea, meaning Ballantine is in no position to argue they justify abandoning the prosecution. Plus, they conflict with the “new things” cited in the Shea motion to dismiss explaining the DOJ flip-flop.

Ballantine creates a case and controversy over whether prosecutorial misconduct occurred

Ballantine presents some things she’s willing to buy off on to argue why DOJ was right to dismiss the prosecution.

But along the way, she contested the central point in Flynn’s argument, that any of this amounted to prosecutorial misconduct.

1 Before Flynn’s 2017 guilty plea, the government provided Flynn with (1) the FBI report for Flynn’s January 24 interview; (2) notification that the DOJ Inspector General, in reviewing allegations regarding actions by the DOJ and FBI in advance of the 2016 election, had identified electronic communications between Strzok and Page that showed political bias that might constitute misconduct; (3) information that Flynn had a sure demeanor and did not give any indicators of deception during the January 24 interview; and (4) information that both of the interviewing agents had the impression at the time that Flynn was not lying or did not think he was lying.

The government subsequently provided over 25,000 pages of additional materials pursuant to this Court’s broad Standing Order, which it issues in every criminal case, requiring the government to produce “any evidence in its possession that is favorable to [the] defendant and material either to [his] guilt or punishment.” Doc. 20, at 2. The majority of those materials, over 21,000 pages of the government’s production, pertain to Flynn’s statements in his March 7, 2017 FARA filing, for which the government agreed not to prosecute him as part of the plea agreement. The remainder are disclosures related to Flynn’s January 24, 2017, statements to the FBI, and his many debriefings with the SCO.

The government disclosed approximately 25 pages of documents in April and May 2020 as the result of an independent review of this case by the United States Attorney for the Eastern District of Missouri. While those documents, along with other recently available information, see, e.g., Doc. 198-6, are relevant to the government’s discretionary decision to dismiss this case, the government’s motion is not based on defendant Flynn’s broad allegations of prosecutorial misconduct. Flynn’s allegations are unfounded and provide no basis for impugning the prosecutors from the D.C. United States Attorney’s Office. [my emphasis]

Ballantine directly contradicts the suggestion made in the Shea motion to dismiss, that any of the documents turned over were new or Brady material; they’ve been demoted to “relevant to.” More importantly, she says that Flynn is wrong to claim either that DOJ said there was misconduct (it did not) or that any misconduct occurred.

Now there’s a case and controversy between DOJ and Flynn. DOJ says no DOJ abuse occurred, in this filing quite explicitly. Flynn says it’s why his prosecution must be dismissed.

While it’s not central to the issue before John Gleeson, it is something he can exploit.

Ballantine dances around DOJ’s shitty materiality claims

Particularly given how Ballantine dances around the main reason DOJ claims it moved to dismiss Flynn’s prosecution, because his lies weren’t material.

This motion was better argued all around than the Main DOJ ones, including the one bearing the Solicitor General’s name. And in numerous places, it presents actual nuance and complexity. One key place it does so is where it admits that DOJ has some motions still pending before Sullivan.

Flynn subsequently retained new counsel. Doc. 88, at 2. He then filed a Brady motion, which the Court denied. Doc. 144, at 2-3. In January 2020, Flynn moved to withdraw his guilty plea, asserting ineffective assistance of prior counsel. Docs. 151, 154, 160. The government has not yet responded to this motion. Flynn also filed a motion to dismiss the case for government misconduct. Doc. 162. In February 2020, the government opposed Flynn’s motion to dismiss. Doc. 169. Flynn repeatedly supplemented the motion after receiving the government’s response, Docs. 181, 188, 189; the government has not submitted a further filing responding to the additional allegations.

On May 7, 2020, while those motions remained pending, the government moved to dismiss the case under Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 48(a). The government first explained a court’s “narrow” role in addressing a Rule 48(a) motion. Doc. 198, at 10 (quoting United States v. Fokker Servs. B.V., 818 F.3d 733, 742 (D.C. Cir. 2016)). The government then set out its reasons for the dismissal, explaining why it had concluded that continued prosecution was not warranted. Id. at 12-20; see pp. 25-32, infra. Flynn consented to the motion. Doc. 202. [my emphasis]

Already this passage presents problems, because Ballantine doesn’t explain why DOJ opposed Flynn’s motion to dismiss in February but does not now, even though none of her “new things” were new in February.

But she doesn’t mention the still-pending DOJ sentencing memorandum, submitted after all the “new things” that Ballantine laid out were already known. That sentencing memorandum not only suggested Flynn should do prison time, but it also argued not only that Flynn’s lies were material, but that Judge Sullivan should consider Flynn’s material FARA lies in his sentencing.

On December 1, 2017, the defendant entered a plea of guilty to a single count of “willfully and knowingly” making material false statements to the Federal Bureau of Investigation (“FBI”) regarding his contacts with the Government of Russia’s Ambassador to the United States (“Russian Ambassador”) during an interview with the FBI on January 24, 2017 (“January 24 interview”), in violation of 18 U.S.C. § 1001(a)(2). See Information, United States v. Flynn, No. 17-cr-232 (D.D.C. Nov. 30, 2017) (Doc. 1); Statement of Offense at ¶¶ 3-4, United States v. Flynn, No. 17-cr-232 (D.D.C. Dec. 1, 2017) (Doc. 4) (“SOF”). In addition, at the time of his plea, the defendant admitted making other material false statements and omissions in multiple documents that he filed on March 7, 2017, with the Department of Justice (“DOJ”) pursuant to the Foreign Agents Registration Act (“FARA”), which pertained to his work for the principal benefit of the Government of Turkey. See SOF at ¶ 5. These additional material false statements are relevant conduct that the Court can and should consider in determining where within the Guidelines range to sentence the defendant.

[snip]

It was material to the FBI’s counterintelligence investigation to know the full extent of the defendant’s communications with the Russian Ambassador, and why he lied to the FBI about those communications.

[snip]

The defendant’s false statements to the FBI were significant. When it interviewed the defendant, the FBI did not know the totality of what had occurred between the defendant and the Russians. Any effort to undermine the recently imposed sanctions, which were enacted to punish the Russian government for interfering in the 2016 election, could have been evidence of links or coordination between the Trump Campaign and Russia. Accordingly, determining the extent of the defendant’s actions, why the defendant took such actions, and at whose direction he took those actions, were critical to the FBI’s counterintelligence investigation.

[snip]

The defendant now claims that his false statements were not material, see Reply at 27-28, and that the FBI conducted an “ambush-interview” to trap him into making false statements, see Reply at 1. The Circuit Court recently stated in United States v. Leyva, 916 F.3d 14 (D.C. Cir. 2019), cert. denied, No. 19-5796, 2019 WL 5150737 (U.S. Oct. 15, 2019), that “[i]t is not error for a district court to ‘require an acceptance of responsibility that extended beyond the narrow elements of the offense’ to ‘all of the circumstances’ surrounding the defendant’s offense.” Id. at 28 (citing United States v. Taylor, 937 F.2d 676, 680-81 (D.C. Cir. 1991)). A defendant cannot “accept responsibility for his conduct and simultaneously contest the sufficiency of the evidence that he engaged in that conduct.” Id. at 29. Any notion of the defendant “clearly” accepted responsibility is further undermined by the defendant’s efforts over the last four months to have the Court dismiss the case. See Reply at 32.

[snip]

Public office is a public trust. The defendant made multiple, material and false statements and omissions, to several DOJ entities, while serving as the President’s National Security Advisor and a senior member of the Presidential Transition Team. As the government represented to the Court at the initial sentencing hearing, the defendant’s offense was serious. See Gov’t Sent’g Mem. at 2; 12/18/2018 Hearing Tr. at 32 (the Court explaining that “[t]his crime is very serious”).

The integrity of our criminal justice depends on witnesses telling the truth. That is precisely why providing false statements to the government is a crime.

[snip]

As the Court has already found, his false statements to the FBI were material, regardless of the FBI’s knowledge of the substance of any of his conversations with the Russian Ambassador. See Mem. Opinion at 51-52. The topic of sanctions went to the heart of the FBI’s counterintelligence investigation. Any effort to undermine those sanctions could have been evidence of links or coordination between the Trump Campaign and Russia. For similar reasons, the defendant’s false statements in his FARA filings were serious. His false statements and omissions deprived the public and the Trump Administration of the opportunity to learn about the Government of Turkey’s covert efforts to influence policy and opinion, including its efforts to remove a person legally residing in the United States.

After the most recent “new thing” Ballantine cited (the DOJ IG Report), in a motion that is still pending before Sullivan, she argued that these lies were material. She doesn’t admit it’s still pending or in any other way deal with it. But Ballantine is making an argument here that conflicts with an argument she signed off on (and spent a great deal of time getting approved by all levels of DOJ) in January.

That presents problems for her claim that the motion to dismiss is the “authoritative position of the Executive.”

The Rule 48(a) motion here represents the authoritative position of the Executive Branch,

A still-pending sentencing memo she signed says Flynn’s lies were material, which conflicts with the pending motion to dismiss. Both are the still-authoritative position of the Executive.

She makes things worse by adopting only one part of Shea’s argument about materiality (though this is consistent with the DC Circuit brief). Shea argued the lies were not material, at all.

The Government is not persuaded that the January 24, 2017 interview was conducted with a legitimate investigative basis and therefore does not believe Mr. Flynn’s statements were material even if untrue.

[snip]

The particular circumstances of this case militate in favor of terminating the proceedings: Mr. Flynn pleaded guilty to making false statements that were not “material” to any investigation. Because the Government does not have a substantial federal interest in penalizing a defendant for a crime that it is not satisfied occurred and that it does not believe it can prove beyond a reasonable doubt, the Government now moves to dismiss the criminal information under Rule 48(a).

[snip]

In the case of Mr. Flynn, the evidence shows his statements were not “material” to any viable counterintelligence investigation—or any investigation for that matter—initiated by the FBI.

[snip]

In light of the fact that the FBI already had these transcripts in its possessions, Mr. Flynn’s answers would have shed no light on whether and what he communicated with Mr. Kislyak.—and those issues were immaterial to the no longer justifiably predicated counterintelligence investigation. Similarly, whether Mr. Flynn did or “did not recall” (ECF No. 1) communications already known by the FBI was assuredly not material.

[snip]

Even if he told the truth, Mr. Flynn’s statements could not have conceivably “influenced” an investigation that had neither a legitimate counterintelligence nor criminal purpose. See United States v. Mancuso, 485 F.2d 275, 281 (2d Cir. 1973) (“Neither the answer he in fact gave nor the truth he allegedly concealed could have impeded or furthered the investigation.”); cf. United States v. Hansen, 772 F.2d 940, 949 (D.C. Cir. 1985) (noting that a lie can be material absent an existing investigation so long as it might “influenc[e] the possibility that an investigation might commence.”). Accordingly, a review of the facts and circumstances of this case, including newly discovered and disclosed information, indicates that Mr. Flynn’s statements were never “material” to any FBI investigation.6

6 The statements by Mr. Flynn also were not material to the umbrella investigation of Crossfire Hurricane, which focused on the Trump campaign and its possible coordination with Russian officials to interfere with the 2016 presidential election back prior to November 2016. See Ex. 1 at 3; Ex. 2 at 1-2. Mr. Flynn had never been identified by that investigation and had been deemed “no longer” a viable candidate for it. Most importantly, his interview had nothing to do with this subject matter and nothing in FBI materials suggest any relationship between the interview and the umbrella investigation. Rather, throughout the period before the interview, the FBI consistently justified the interview of Flynn based on its no longer justifiably predicated counterintelligence investigation of him alone.

Shea further argued that Sullivan’s past judgment that these lies were material came before DOJ’s view on the case changed.

7 The Government appreciates that the Court previously deemed Mr. Flynn’s statements sufficiently “material” to the investigation. United States v. Flynn, 411 F. Supp. 3d 15, 41-42 (D.D.C. 2019). It did so, however, based on the Government’s prior understanding of the nature of the investigation, before new disclosures crystallized the lack of a legitimate investigative basis for the interview of Mr. Flynn, and in the context of a decision on multiple defense Brady motions independent of the Government’s assessment of its burden of proof beyond a reasonable doubt.

Ballatine does parrot Shea’s claim that “additional information” has emerged since Sullivan ruled.

In any event, additional information that was not before the Court emerged in the months since the decision that significantly alters the analysis.

The problem, here, is that in her filing, that’s as much a false claim as Shea’s claim to have found “new things” were. Ballantine’s “new things” was all known to the government well before Sullivan ruled.

As to materiality itself, the only part of Shea’s argument about materiality that Ballantine adopts pertains to whether she could prove it.

The government expressed concern specifically about its ability to prove materiality.

[snip]

The government’s Rule 48(a) motion accordingly explained that it doubted whether, in light of those aspects of the record, it should attempt to prove to a jury that the information was objectively material.

Which, as Gleeson has pointed out, doesn’t matter given Flynn’s past guilty plea.

Perhaps because of that, Ballantine adopts a different approach than Shea did in arguing that Sullivan’s past ruling didn’t matter. She argues that only a jury can decide materiality.

But as the Supreme Court has held, determining whether information is material is an essential element of the crime that must be determined by a jury, and cannot be determined as a matter of law by a court. United States v. Gaudin, 515 U.S. 506, 511- 512, 522-523 (1995). Indeed, the materiality inquiry is “peculiarly one for the trier of fact” because it requires “delicate assessments of the inferences a reasonable decision-maker would draw from a given set of facts and the significance of those inferences to him.” Id. at 512 (internal quotation marks and brackets omitted). For that reason, the Court’s determination could not resolve the government’s concerns about its materiality case at trial.

But then she imagines what the jury might think about the materiality of Flynn’s lies that — much of the subsequent developments make clear — actually did affect the investigation into him.

Amicus makes much of the fact that a defendant’s false statements can be material even when the investigators are not deceived by them, accusing the government of asking for “the suspension of settled law for this case, but not for any others.” Gleeson Br. 46-47 (citing United States v. Safavian, 649 F.3d 688, 691-692 (D.C. Cir. 2011) (per curiam)). Contrary to amicus’s assertion (at 46-47), however, that is entirely consistent with the government’s analysis. In Safavian, the D.C. Circuit rejected a defendant’s argument that his false statements were not material where the interviewing FBI agent “knew, based upon his knowledge of the case file, that the incriminating statements were false when [the defendant] uttered them.” 649 F.3d at 691. As the government recognized in its motion to dismiss, the fact that the FBI knew at the time it interviewed Flynn the actual contents of his conversations with Kislyak does not render them immaterial. See Doc. 198, at 17 (citing Safavian, 649 F.3d 688 at 691-692). Rather, the fact that the FBI knew the content of the conversations is relevant because it would allow a jury to assess the significance the FBI in fact attached to that truthful information when the FBI learned it; and, absent reason to think that the FBI’s reaction was objectively unreasonable, that would inform the jury’s assessment of the significance a reasonable decision-maker would attach to the information.

Shea’s argument was — as Gleeson made clear — legally indefensible. Ballantine’s is legally more defensible. Except that she has already argued more persuasively against herself, in a still-pending filing that is, like the motion to dismiss, the authoritative position of the Executive Branch.

Ballantine’s argument here is more persuasive then — though inconsistent with — Shea’s. Except that she’s arguing with a still more persuasive Ballantine memorandum that remains before Sullivan.

Not only is DOJ arguing with DOJ, but Jocelyn Ballantine is arguing with Jocelyn Ballantine

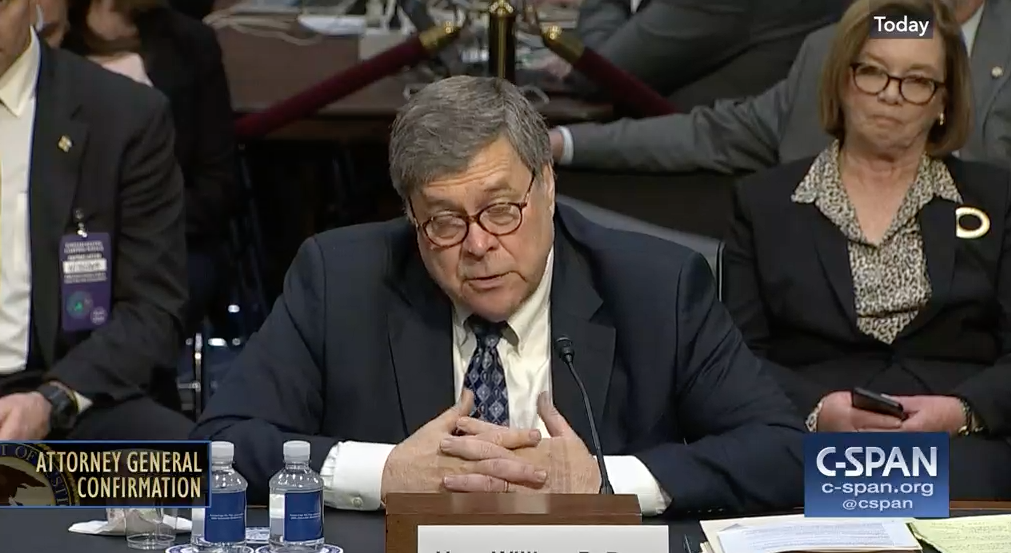

With DOJ’s motion to dismiss, Bill Barr’s DOJ argued against what Bill Barr’s DOJ argued in a still pending sentencing memo submitted in January. DOJ’s response in the DC Circuit mandamus petition argued against Bill Barr’s admission that Emmet Sullivan has a say in whether to dismiss the case or not. Now, Jocelyn Ballantine is arguing that DOJ’s past (but still-pending) statements about materiality conflict with its current statements.

The DC Circuit filing and this one conflict with Shea about what the “new things” are justifying such flip-flops.

But crazier still, Ballantine argues that these conflicting statements are the authoritative view, singular, of the Executive.

Ballantine has laid out a case and controversy with Sullivan here — whether her own conduct amounted to misconduct. Sullivan’s amicus, John Gleeson, may well be able to use that to argue that the many conflicting statements from DOJ make it clear there is no authoritative view from the Executive, because it can’t agree with itself — its prosecutor can’t even agree with herself — on a week to week basis.

And if there is no one authoritative authoritative view of the Executive, Sullivan will have a much easier time arguing all this overcomes any presumption of regularity.