Verizon Counsel Speaks Out Against “Outsourcing” Intelligence

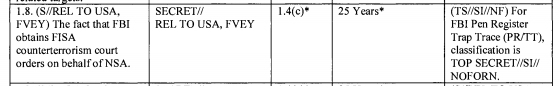

One of the concerns I’ve raised about HR 3361 — AKA USA Freedumber — regards who will do some of the data analysis that the NSA “data integrity analysts” currently do before the contact-chaining stage. As I’ve noted, the most privacy protective thing would be to have the telecoms do it, but that would put them in an inappropriate role of performing analysis for the intelligence community.

Apparently, Verizon agrees with that. As part of Verizon Associate General Counsel Michael Woods’ testimony to the Senate Intelligence Committee the other day, he emphasized how inappropriate it would be for the telecoms to serve as surrogates for the intelligence community. (He emphasized this in his answers as well.)

Included in the reform discussions has been the idea that the collection, searching, and perhaps even analysis, of potentially relevant data is best done not by the government, but by the private holders of that data. One recommendation that garnered particular attention was that bulk collection of telephony metadata might be replaced by a system in which such metadata is held instead either by private providers or by a private third party.

This proposal opens a very complex debate, even when that debate is restricted to just traditional telephony, but the bottom line is this: national security is a fundamental government function that should not be outsourced to private companies.

Verizon is in the business of providing communications and other services to our customers. Data generated by that process is held only if, and only for long as, there is a business purpose in doing so. Outside of internal business operations, there typically is no need for companies to retain data for extended periods of time.

If a company is required to retain data for the use of intelligence agencies, it is no longer acting pursuant to a business purpose. Rather, it is serving the government’s purpose. In this context, the company has become an agent or surrogate of the government. Any Constitutional benefit of having the data held by private entities is lost when, by compelling retention of that data for non-business purposes, the private entity becomes a functional surrogate of the government. Public trust would exist to the extent that companies are believed to be truly independent of the government. When the companies are seen as surrogates for intelligence agencies, such trust will dissipate.

Nor would outsourcing offer any promise of efficiency. Technology is changing too rapidly — telecommunications networks are evolving beyond traditional switched telephony. Voice over Internet Protocol (VoIP) technologies handle voice traffic over the Internet (as opposed to the public switched telephone networks) and already account for a substantial portion of voice traffic. Even more dramatic has been the rise of “over-the-top” applications that use peer to peer or other technologies to establish direct connections between users over the Internet. In 2012, one such application accounted for 34% of all international voice calling minutes. VoIP and over-the-top applications traverse IP networks as Internet traffic and thus do not generate CDRs or similar telephony business records. U.S. intelligence agencies would need to approach application owners to establish access equivalent to the CDRs they obtain under the existing program. The technical difficulties multiply if the intelligence agencies were to eventually seek the same sort of access to IP metadata from Internet Service Providers.

Finally, the commercial effect on U.S. companies of outsourcing collection ought to be considered. No company will be eager to undertake the increased responsibility, scrutiny, and liability entailed by having its employees become surrogates for the government in the collection of intelligence. More troubling for large companies is the negative effect in the international market of overt association with a U.S. intelligence agency.

H.R. 3361 does not include any provisions which would require data retention by telecommunications companies. For all the foregoing reasons, that is a good thing. A framework under which intelligence agencies retain and analyze data that has been obtained from telecommunications companies in a “arms length” transaction compelled by a FISA order should continue. [my emphasis]

I quote this in full not to make you laugh at the prospect of Verizon balking at “becoming” a surrogate of the government.

I think this statement was clearly meant to lay out some clear principles going forward (and I suspect Verizon is by far the most important player in USA Freedumber, so Congress may well listen). Whatever Verizon has done in the past — before Edward Snowden and after him, ODNI exposed it, alone among the telecom companies, as turning over all our phone records to the government — it has made several efforts, some half-hearted and some potentially more significant to establish some space between it and the government. If Verizon has decided it’s time to set real boundaries in its cooperation with the government I’m all in favor of that going forward.

Much of this statement is just a clear warning that Verizon won’t abide by requests to extend their data retention practices, which it terms acting as an agent of the government. That will, by itself, limit the program. As Woods explained, they don’t really need Call Detail Records that long (and I assume they need smart phone data even less). What they keep the required 18 months is just billing records, which doesn’t provide the granular data the government would want. So if Verizon refuses to change its data retention approach, it will put a limit on what the government can access.

That said, that’s clearly what a number of Senators would like to do — mandate the retention of CDRs 18 months, which would in turn significantly raise the cost of this (about which more in a later post). So this could actually become a quite heated battle, aside from what privacy activists do.

There are a few more details of this I’m particularly intrigued by (aside from Woods’ warning that the records of interest will all be Internet-based calls within very short order).

Note that Woods admits there has been some discussion of having telecoms do “analysis” (and I assume he’s not talking just about me). Given his statements, it seems Verizon would refuse that too (good!). But remember: the last round of USA Freedumbing included compensation and immunity for Booz-type contractors in addition to the telecoms, so NSA may still be outsourcing this analysis, just to other contractors (and given that this was a late add, it may have come in response to Verizon’s reluctance to do NSA’s analysis for it).

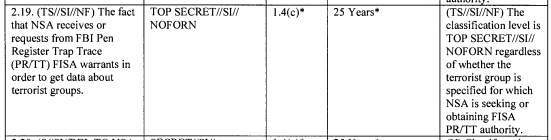

When Woods claims this is difficult, “even when that debate is restricted to just traditional telephony,” he suggests the debate may not be restricted to traditional telephony. Obviously, Verizon must still be involved in upstream production. And it either is or may well be asked to resume its involvement in Internet metadata collection, because USA Freedumber doesn’t hide the intent to return to Internet dragnet collection. Then there’s the possibility Mark Warner’s questions elicited, that the telecoms will be getting hybrid orders asking for telephony metadata as well as other things, not limited to location.

When we talk about the various ways the NSA may try to deputize the telecoms, the possibilities are very broad — and alarming. So I’m happy to hear that Verizon, at least, is claiming to be unwilling to play that role.