Tom Bossert Brings You … Axis of CyberEvil!

I was struck, when reviewing the NYT article on the KT McFarland email, how central Homeland Security Czar Tom Bossert was to the discussion of asking Russia not blow off Obama’s Russia sanctions.

“Key will be Russia’s response over the next few days,” Ms. McFarland wrote in an email to another transition official, Thomas P. Bossert, now the president’s homeland security adviser.

[snip]

Mr. Bossert forwarded Ms. McFarland’s Dec. 29 email exchange about the sanctions to six other Trump advisers, including Mr. Flynn; Reince Priebus, who had been named as chief of staff; Stephen K. Bannon, the senior strategist; and Sean Spicer, who would become the press secretary.

[snip]

Mr. Bossert replied by urging all the top advisers to “defend election legitimacy now.”

[snip]

Obama administration officials were expecting a “bellicose” response to the expulsions and sanctions, according to the email exchange between Ms. McFarland and Mr. Bossert. Lisa Monaco, Mr. Obama’s homeland security adviser, had told Mr. Bossert that “the Russians have already responded with strong threats, promising to retaliate,” according to the emails.

There Tom Bossert was, with a bunch of political hacks, undercutting the then-President as part of an effort to “defend election legitimacy now.”

Which is one of the reasons I find Bossert’s attribution of WannaCry to North Korea — in a ridiculously shitty op-ed — so sketchy now, as Trump needs a distraction and contemplates an insane plan to pick a war with North Korea.

The guy who — well after it was broadly known to be wrong — officially claimed WannaCry was spread by phishing is now offering this as his evidence that North Korea is the culprit:

We do not make this allegation lightly. It is based on evidence.

A representative of the government whose tools created this attack, said this without irony.

The U.S. must lead this effort, rallying allies and responsible tech companies throughout the free world to increase the security and resilience of the internet.

And the guy whose boss has, twice in the last week, made googly eyes at Vladimir Putin said this as if he could do so credibly.

As we make the internet safer, we will continue to hold accountable those who harm or threaten us, whether they act alone or on behalf of criminal organizations or hostile nations.

Much of the op-ed is a campaign ad falsely claiming a big break with the Obama Administration.

Change has started at the White House. President Trump has made his expectations clear. He has ordered the modernization of government information-technology to enhance the security of the systems we run on behalf of the American people. He continued sanctions on Russian hackers and directed the most transparent and effective government effort in the world to find and share vulnerabilities in important software. We share almost all the vulnerabilities we find with developers, allowing them to create patches. Even the American Civil Liberties Union praised him for that. He has asked that we improve our efforts to share intrusion evidence with hacking targets, from individual Americans to big businesses. And there is more to come.

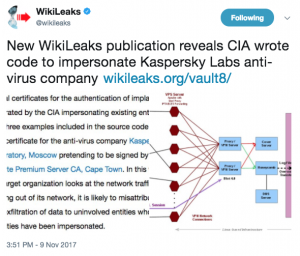

A number of the specific items Bossert pointed to to claim action are notable for the shoddy evidence underlying them, starting with the Behzad Mesri case and continuing to Kaspersky — which has consistently had more information on the compromises we blame it for than the US government.

When we must, the U.S. will act alone to impose costs and consequences for cyber malfeasance. This year, the Trump administration ordered the removal of all Kaspersky software from government systems. A company that could bring data back to Russia represents an unacceptable risk on federal networks. Major companies and retailers followed suit. We brought charges against Iranian hackers who hacked several U.S. companies, including HBO. If those hackers travel, we will arrest them and bring them to justice. We also indicted Russian hackers and a Canadian acting in concert with them. A few weeks ago, we charged three Chinese nationals for hacking, theft of trade secrets and identity theft. There will almost certainly be more indictments to come.

The Yahoo case, which is backed by impressive evidence, was based on evidence gathered under Obama, from whose Administration Bossert claims to have made a break.

And this kind of bullshit — in an op-ed allegedly focused on North Korea — is worthy of David Frum playing on a TRS-80.

Going forward, we must call out bad behavior, including that of the corrupt regime in Tehran.

Especially ending as it does with a thinly disguised call for war.

As for North Korea, it continues to threaten America, Europe and the rest of the world—and not just with its nuclear aspirations. It is increasingly using cyberattacks to fund its reckless behavior and cause disruption across the world. Mr. Trump has already pulled many levers of pressure to address North Korea’s unacceptable nuclear and missile developments, and we will continue to use our maximum pressure strategy to curb Pyongyang’s ability to mount attacks, cyber or otherwise.

I mean, maybe dirt poor North Korea really did build malware designed not to make money. But this is not the op-ed to credibly make that argument.

![[Photo: National Security Agency, Ft. Meade, MD via Wikimedia]](https://www.emptywheel.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/NationalSecurityAgency_HQ-FortMeadeMD_Wikimedia.jpg)