Who Cooked Adam Smith’s Dinner?

Who Cooked Adam Smith’s Dinner? is the title of a 2012 (2016 in the US) book by Katrine Marçal, a Swedish journalist. The title question is based on a famous bit from Adam Smith’ The Wealth of Nations*:

It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest.

But the butcher, the brewer and the baker did not cook for Smith. That job went to his mother, Margaret Douglas, later joined by his cousin, Jane Dauglas. These women took care of Smith’s household until they died. Smith never mentions their labor.

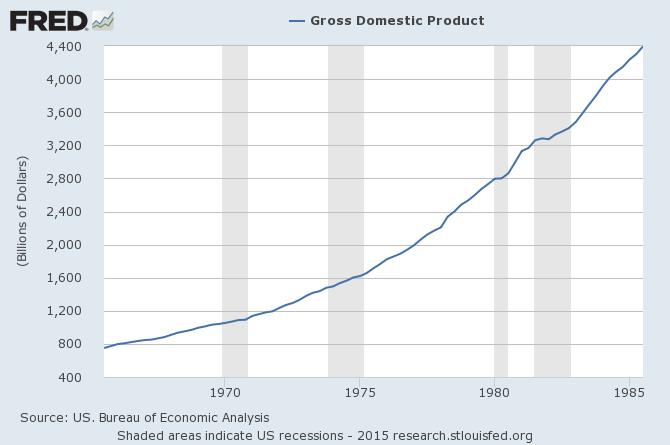

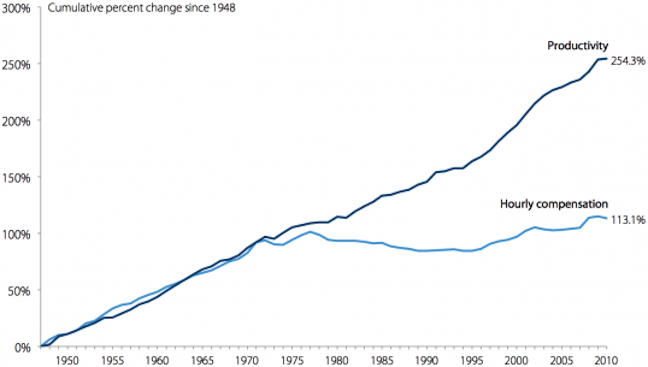

Marçal explores the impact of Smith’s omission on the study of economics. One thread is the feminist story: much of the crucial work of care is provided through benevolence, not for money, and so it not considered part of the economy or part of the field studied by economists. Marçal points out that when an economist marries his housekeeper, the GDP goes down.

Smith’s omission makes ti possible to make “markets” the center of the study of economics. Eventually theorists dreamed up the silly story of Homo Economicus with his rational calculation of individual advantage as the essential human characteristic. We identify that rationality as masculine as opposed to feminine in the context of male-centered history and culture. In feminist terms, homo economicus is ungendered and dominant; women are the other in every way.

Instead of this stunted theory, Marçal shows that the economy isn’t just about the production of things for the market. A huge part of the work of any society is care for one another. We care for children, for the aged, the sick, the abandoned, the orphan and the widow, those injured in war and those injured in mind. We care for our planet, our air, our parks and our public spaces, our cities, our lakes and rivers. Much of that care has nothing to do with markets. We do it solely out of benevolence, in direct contradiction to Smith.

If economists are ignoring the importance of care in the functioning of an economy, what are they doing? They tell us that they study the allocation of scarce resources. This is from the introductory textbook Economics by Samuelson and Nordhaus, 18th Ed. 2005:

Economics is the study of how societies use scarce resources to produce valuable commodities and distribute them among different people. Id. at 4.

Scarcity and efficiency are the important elements of this definition. Care for the vulnerable must not involve a scarce resource under this definition, probably because everyone blithely assumes that women will do it for free, and there are plenty of women. Importantly, care isn’t controlled by the demands of efficiency. If the baby cries, what does it even mean to talk about efficiency? We do whatever it takes and for as long as it takes. So taking care of each other is excluded from the study of economics from the outset under Samuelson’s definition.

In his textbook Introduction to Macroeconomics, 6th Ed. 2012, N. Gregory Mankiw quotes the 19th C. British economist Alfred Marshall: “Economics is a study of mankind in the ordinary business of life.”. Id. at viii. I’d guess Marshall meant “Malekind”. Mankiw adds that The word economics springs from a Greek word meaning household, and he talks about how households have to make decisions about who goes to work and who cooks, and who gets the extra dessert. Then he drops the idea that cooking dinner is part of the economy. Apparently when Mankiw talks about the ordinary business of life, he means “male business”, not changing poopy diapers or making dinner. It’s funny when you see it from the perspective Marçal demonstrates.

Of course Marçal is right to say that economics ignores a huge chunk of the work necessary to maintain us in the ordinary business of our lives. That doesn’t make it useless, to be sure. Marçal points out the utility of the data and statistics gathered by economists. But it does mean that the models economists are creating are likely to be useless because they purposefully ignore a crucial element of ordinary life. And it means that economics isn’t a plausible basis for thinking about human nature.

The book is informed by feminist theory, but it isn’t theoretical. It is an application of feminist theory to economics. Marçal uses uses words like “gendered”; and she writes:

It’s only woman who has a gender. Man is human. Only one sex exists. The other is a variable, a reflection, complementary. P. 159.

Then she gives concrete examples that make the meanings perfectly clear for people like me who don’t know anything about feminist theory. The result is that I began to leann a little about the theory, and it was much easier than trying to learn it on my own from primary sources**.

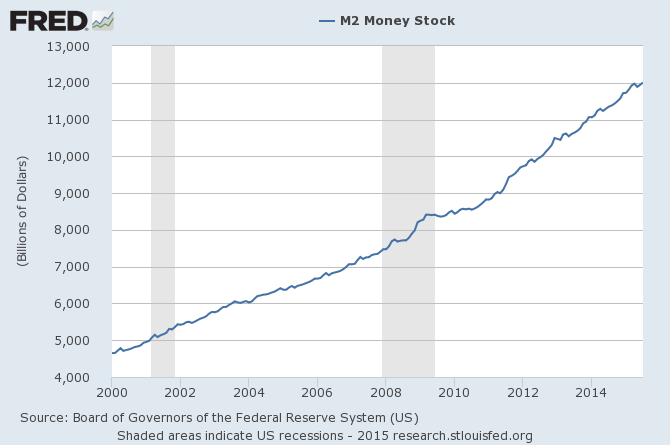

Marçal devotes several chapters to eviscerating the economists dream person, Homo Economicus, the ungendered center of their universe, the Man we all must become. These chapters expose the shallow thinking that neoliberal economists like Gary Becker bring to the discussion of human nature. She makes neoliberalism look childish and silly. I particularly liked the discussion of the hidden emotional vulnerabilities of neoliberal Man. We have to coddle Mr. Market, and steady him when he gets the jitters, which happens all the time, and which, of course, requires tons of money.

Marçal writes clear, direct and engaging prose. Like every good book this one clarified several inchoate ideas that have been floating around in my head, and it gave me several new ideas I hope to take up in future posts. I am grateful to my excellent daughter who gave me this book.

==========

* Here it is in context. I leave for my skeptical readers the pleasure of picking at the holes in this passage.

// In almost every other race of animals, each individual, when it is grown up to maturity, is entirely independent, and in its natural state has occasion for the assistance of no other living creature. But man has almost constant occasion for the help of his brethren, and it is in vain for him to expect it from their benevolence only. He will be more likely to prevail if he can interest their self-love in his favour, and shew them that it is for their own advantage to do for him what he requires of them. Whoever offers to another a bargain of any kind, proposes to do this. Give me that which I want, and you shall have this which you want, is the meaning of every such offer; and it is in this manner that we obtain from one another the far greater part of those good offices which we stand in need of. It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest. We address ourselves, not to their humanity, but to their self-love, and never talk to them of our own necessities, but of their advantages.//

**Another good book for this purpose is Possession, by A.S. Byatt.