Charlie Savage Plays with His Magic Time Machine To Avoid Doing Journalism

Charlie Savage just did something astonishing in the name of press freedom. He said that the truth doesn’t matter now, in 2021, because he reported a different truth eleven years ago.

He took issue with my headline to this piece, noting that he was obfuscating the facts about the Julian Assange prosecution so as to shoehorn it into a story about actual journalists.

Charlie made several obfuscations or clear errors in that piece:

- He didn’t explain (as he hasn’t, to misleading effect, in past stories on Assange) the nature of the 2nd superseding indictment and the way it added to the most problematic first superseding one

- He said the 2019 superseding indictment (again, he was silent about the 2020 superseding indictment) raised the “specter of prosecuting reporters;” this line is how Charlie shoehorned Assange into a story about actual journalists

- He claimed that the decision to charge Assange for “his journalistic-style acts” arose from the change in Administrations, Obama to Trump (and specifically to Bill Barr), not the evidence DOJ had obtained about Assange’s actions over time

Charlie presented all this as actual journalism about the Assange prosecution, but along the way, he made claims that were either inflammatory and inexact — a veritable specter haunting journalism — or, worse, what I believe to be false statements, false statements that parrot the propaganda that Wikileaks is spreading to obscure the facts.

The “specter” comment, I take to be a figure of speech, melodramatic and cynical, but mostly rhetorical.

The silence about the 2020 superseding indictment is a habit I have called Charlie on before, but one that is an error of omission, rather than of fact.

It’s this passage that I objected to at length:

But the specter of prosecuting reporters returned in 2019, when the department under Attorney General William P. Barr expanded a hacking conspiracy indictment of Julian Assange, the WikiLeaks founder, to treat his journalistic-style acts of soliciting and publishing classified information as crimes.

Obama-era officials had weighed charging Mr. Assange for publishing leaked military and diplomatic files, but worried about establishing a precedent that could damage mainstream news outlets that sometimes publish government secrets, like The Times. The Trump administration, however, was undeterred by that prospect.

As presented, this passage made several claims:

- “Obama-era officials” had considered charging Assange for publishing activities, but “Obama-era officials” did not do so because it might damage “mainstream news outlets” like the NYT

- The reason that the Trump administration was willing to charge Assange for publishing was because they were “undeterred” from the prospect of doing damage to the NYT

- DOJ under Billy Barr expanded a hacking conspiracy “to treat his journalistic-style acts of soliciting and publishing classified information as crimes”

I believe the last claim is largely factual but misleading, as if the operative issue were Barr’s involvement or as if Barr deliberately treated Assange’s “journalistic-style acts” — as distinct from that of actual journalists — as a crime. There may be evidence that Barr specifically had it in for WikiLeaks or that Barr (as distinct from Trump’s other Attorneys General) treated Assange as he did out of the same contempt with which he treated actual journalists. There may be evidence that Barr — whose tenure as AG exhibited great respect for some of the journalists he had known since his first term as AG — was trying to burn down journalism, as an institution. But Charlie provides no evidence of that, nor has anyone else I know. (Indeed, Charlie’s larger argument presents evidence that Barr’s attacks on journalism, including subpoenas that may or may not have been obtained under Barr in defiance of guidelines adopted under Eric Holder, may only differ from Obama’s in their political tilt.)

Of course, one of the worst things that the Trump Administration did to a journalist, obtaining years of Ali Watkins’ email records, happened under Jeff Sessions, not Barr.

The first and second claims together set up a clear contrast. Obama-era officials — and by context, this means the entirety of the Obama Administration — did not prosecute Assange for publication because of what became known — based off a description that DOJ’s spox Matthew Miller gave publicly in 2013 — as the NYT problem, the risk that prosecuting WikiLeaks would endanger NYT. But the Trump Administration was willing to charge Assange for publication because they didn’t think the risk that such charges posed to the NYT were all that grave or damaging or important.

There’s no way to understand these two points except as a contrast of Administrations, to suggest that Obama’s Administration — which was epically shitty on leak investigations — wouldn’t do what the Trump Administration did do. It further involves treating the Department of Justice as an organization entirely subject to the whims of a President and an Attorney General, rather than as the enormous bureaucracy full of career professionals who guard their independence jealously, who even did so, with varying degrees of success, in the face of Barr’s unprecedented politicization of the department.

It’s certainly possible that’s true. It’s possible that Evan Perez and three other CNN journalists who reported in 2017 that what actually changed pertained to Snowden simply made that report up out of thin air. It’s certainly possible that under a President who attempted to shut down the Russian hacking investigation to protect Assange even after his CIA Director declared war on Assange, who almost blew up the investigation into Joshua Schulte, who entertained pardoning Assange in 2016, in 2017, in 2018, and in 2020, at the same time viewed the Assange prosecution as a unique opportunity to set up future prosecutions of journalists. It’s certainly possible that Billy Barr, who sabotaged the Mike Flynn and Roger Stone prosecutions to serve Trump’s interests, went rogue on the Assange case.

But given the abundant evidence that this prosecution happened in spite of Trump’s feelings about WikiLeaks rather than because of them, you would need to do actual reporting to make that claim.

And, as noted, I asked Charlie whether he had done the reporting to sustain that claim before I wrote the post…

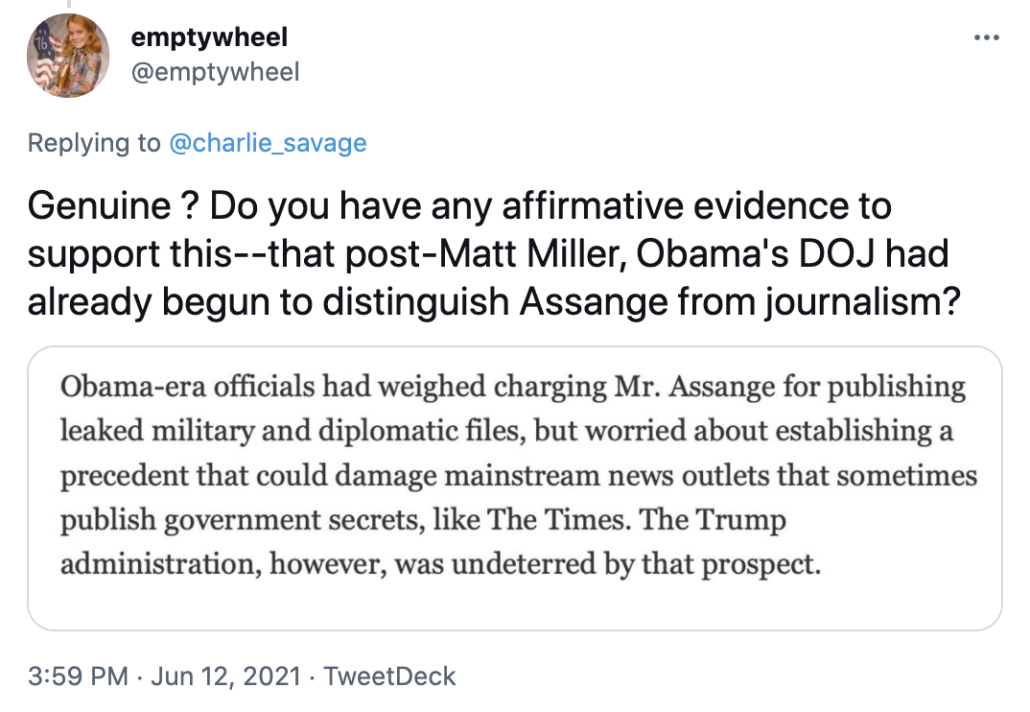

… just as I — months earlier — asked Charlie why he was falsely claiming Assange was charged in 2018 rather than within a day of a Russian exfiltration attempt in 2017, something that probably has far more to do with why DOJ charged Assange when and how they did than who was Attorney General at the time.

After his bullshit attempt to explain that date error away, Charlie removed the date, though without notice of correction, must less credit to me for having to fact check the NYT.

Anyway, Charlie apparently didn’t read the post when I first wrote it, but instead only read it yesterday when I excused Icelandic journalists for making the same error — attributing the decision to prosecute Assange to Billy Barr’s animus rather than newly discovered evidence — that Charlie had earlier made. And Charlie went off on a typically thin-skinned tirade. He accused me (the person who keeps having to correct his errors) of being confused. He claimed that the thrust of my piece — that he was misrepresenting the facts about Assange — was “false.” He claimed the charges against and extradition of Assange was a precedent not already set by Minh Quang Pham’s extradition and prosecution. He accused me of not grasping that this was a First Amendment argument and not the journalism argument he had shoehorned it into. He suggested my insistence on accurate reporting about the CFAA overt acts against Assange (including the significance of Edward Snowden to them) was a “hobbyhorse,” and that I only insisted on accurate reporting on the topic in an effort to, “us[e] something [Charlie] said as a peg to artificially sex it up (dumb NYT!) even though it doesn’t actually fit.” He then made a comment that still treats the prosecution of Assange as binary — the original indictment on a single CFAA charge or the first superseding indictment that added the dangerous Espionage Act charges — rather than tertiary, the second superseding indictment that, at least per Vanessa Baraitser, clearly distinguished what Assange did from what journalists do.

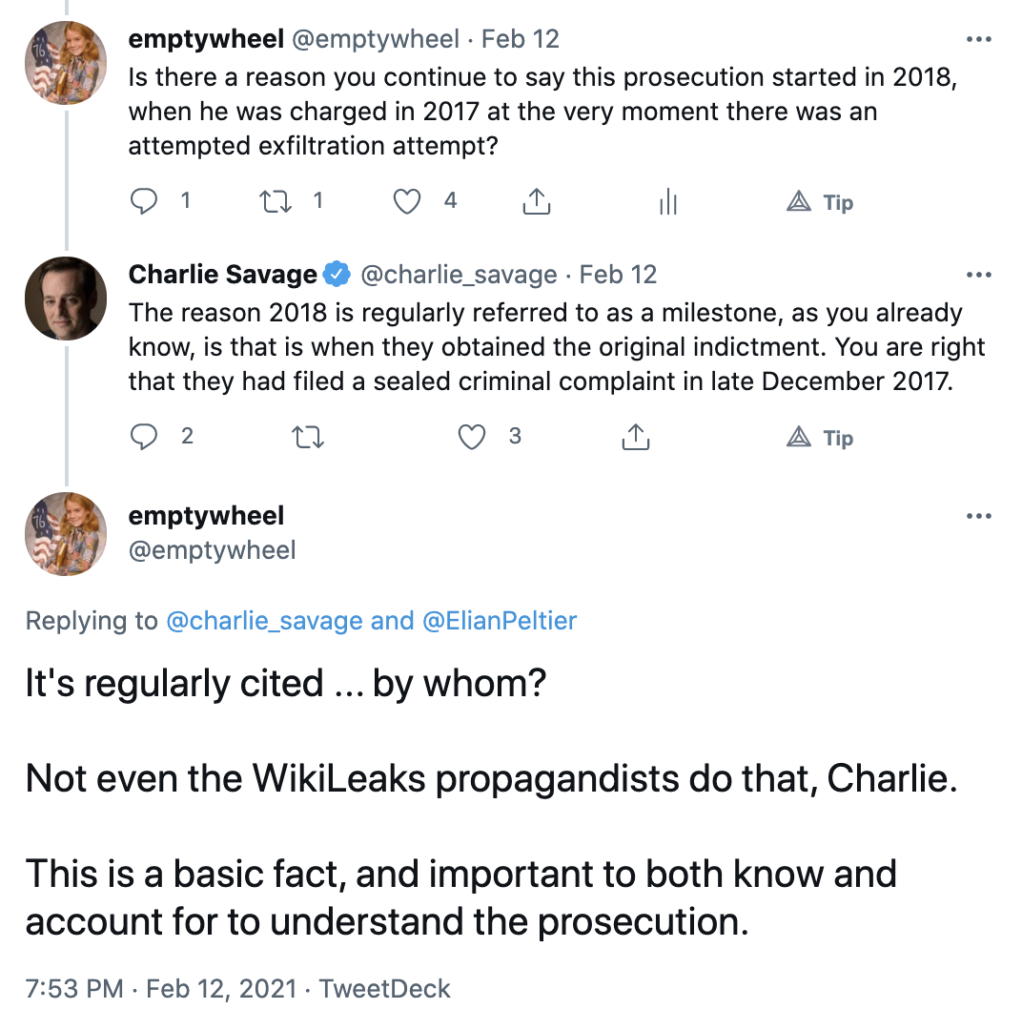

That’s when things went absolutely haywire. Pulitzer prize winning journalist Charlie Savage said that his repeated claim that the charges against Assange arose from a change in Administration rather than a changed understanding of Assange did not rely on what Miller said, because he had “been writing since 2010 about deliberations inside DOJ re wanting to charge Assange/WL,” linking to this story.

That is, Charlie presented as a defense to my complaint that he was misrepresenting what happened in 2016 and 2017 by pointing to reporting he did in 2010, which — I pointed out — is actually before 2013 and so useless in offering a better reason to cling to that 2013 detail rather than rely on more recent reporting. Because DOJ did not have the same understanding of WikiLeaks in 2010 as they got after Julian Assange played a key role in a Russian intelligence operation against the United States, obtained files from a CIA SysAdmin after explicitly calling on CIA SysAdmins to steal such things (in a speech invoking Snowden), attempted to extort the US with those CIA files, and then implicitly threatened the President’s son with them, Charlie Savage says, it’s okay to misrepresent what happened in 2016 and 2017. Charlie’s reporting in 2010 excuses his refusal to do reporting in 2021.

Given his snotty condescension, it seems clear that Charlie hasn’t considered that, better than most journalists in the United States, I understand the grave risks of what DOJ did with Assange. I’ve thought about it in a visceral way that a recipient of official leaks backed by an entire legal department probably can’t even fathom. But that hasn’t stopped me from trying to understand — and write accurately about — what DOJ claims to be doing with Assange. Indeed, as someone whose career has intersected with WikiLeaks far more closely than Charlie’s has and as someone who knows what people very close to Assange claim to believe, I feel I have an obligation to try to unpack what really happened and what the real legal implications of it are, not least because that’s the only way to assess where DOJ is telling the truth and whether they’re simply making shit up to take out Assange. DOJ is acting ruthlessly. But at the same time, at least one person very close to Assange told me explicitly she wanted me to misrepresent the truth in his defense, and WikiLeaks has been telling outrageous lies in Assange’s defense with little pushback by people like Charlie because, I guess, he thinks he’s defending journalism.

As I understand it, the entire point of journalism is to try to write the truth, rather than obfuscate it in an attempt to protect an institution called journalism. It does no good to the institution — either its integrity or the ability to demonstrate the risks of the Assange prosecution — to blame it all on Billy Barr rather than explore how and why DOJ’s institutional approach to Assange has changed over time.