The Two Smear Attacks against Jeff Bezos and His Partner

Jeff Bezos doesn’t tweet much.

On July 14, he proclaimed that, “Our former President showed tremendous grace and courage” after being shot.

On November 6, shortly after spiking a WaPo editorial describing how unfit Trump is to be President, Bezos congratulated “our 45th and now 47th President on an extraordinary political comeback and decisive victory.”

On November 21, Bezos debunked Elon Musk’s claim that Bezos, “was telling everyone that @realDonaldTrump would lose for sure, so they should sell all their Tesla and SpaceX stock.” “100% not true,” Bezos replied, without noting how Elon had conflated Trump’s success with his own, including the rocket company that directly competes with Bezos’ own spaceship project.

By December 20, Bezos had found common cause with his rival. Both shifting people from the “low productivity” government sector to the “high productivity” private sector and deregulation “results in greatly increased prosperity,” the richest man in the world said. “Both of these are correct and the first is widely under appreciated,” the second richest man replied. Neither clarified whether the “greatly increased prosperity” in question was their own, or that of the people out o f their secure government job.

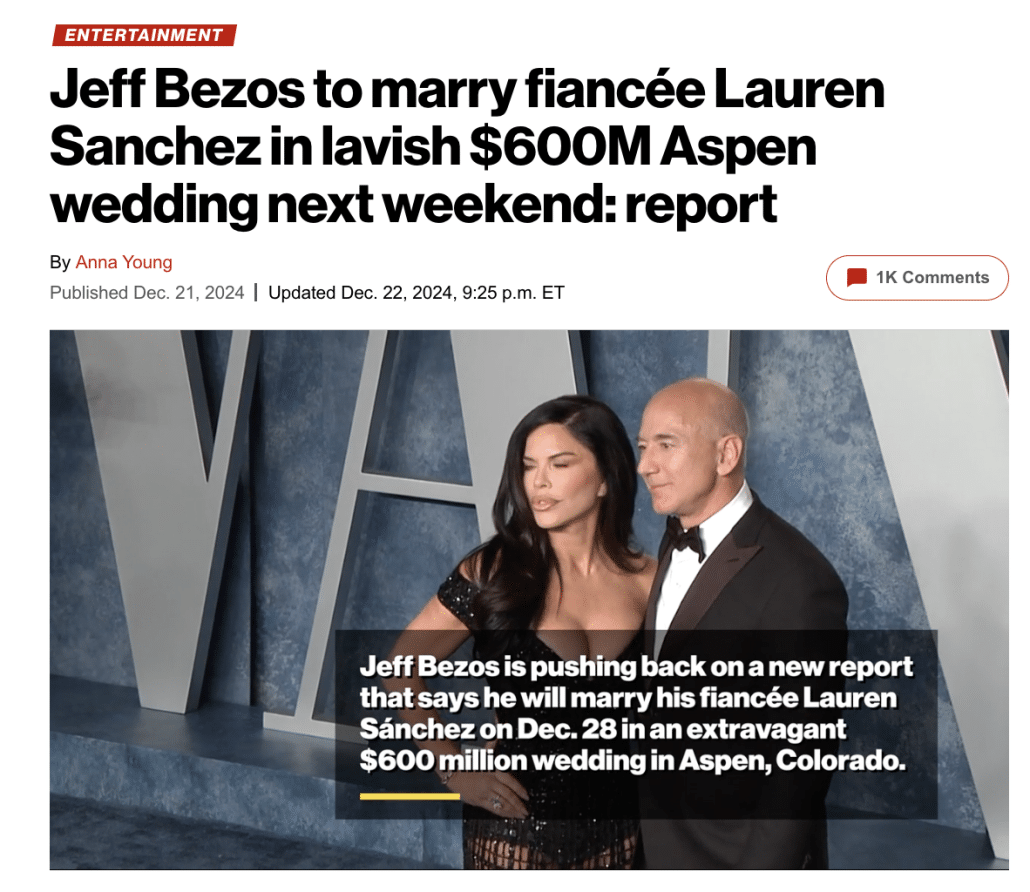

When Bezos RTed Bill Ackman’s explanation of why a New York Post story claiming” Jeff Bezos to marry fiancée Lauren Sanchez in lavish $600M Aspen wedding next weekend” was not credible. “Unless you are buying each of your guests a house, you can’t spend this much money,” then, it was just his fifth tweet since February.

The owner of the Washington Post engaged in a bit of press criticism in that tweet, apparently denying not just that he’s dropping $600M on a party, but that the party would happen this week at all (I believe the date of the purported wedding has now passed with no wedding).

Furthermore, this whole thing is completely false — none of this is happening. The old adage “don’t believe everything you read” is even more true today than it ever has been. Now lies can get ALL the way around the world before the truth can get its pants on. So be careful out there folks and don’t be gullible.

Will be interesting to see if all the outlets that “covered” and re-reported on this issue a correction when it comes and goes and doesn’t happen.

Bezos — whose rag (according to a Will Lewis interview with Ben Smith) specifically pointed to brainless dick pic sniffing about Hunter Biden that didn’t correct WaPo’s past errors to rebut claims of bias — believed he’d get “corrections” to salacious stories from Daily Mail and NY Post of the kind that made Hunter Biden dick pics A Thing.

Let me state that more clearly. A man whose newspaper chose to respond to political pressure by letting the Daily Mail and NYPost and Fox News serve as assignment editors for his journalists demanded that the Daily Mail and NYPost adhere to a higher standard than the still-uncorrected WaPo.

That’s why I decided to revisit this incident after watching this exchange, about the problems with traditional journalistic efforts to achieve objectivity in the face of asymmetric approaches to truth.

Bezos, of course, tried to explain his decision to intervene in the content of his rag (by spiking the Kamala Harris endorsement) by suggesting WaPo simply isn’t being realistic about perceptions of bias, then adding to perceptions of bias by failing to disclose all the conflicts that might have led him to curry favor with Trump.

In the annual public surveys about trust and reputation, journalists and the media have regularly fallen near the very bottom, often just above Congress. But in this year’s Gallup poll, we have managed to fall below Congress. Our profession is now the least trusted of all. Something we are doing is clearly not working.

[snip]

Likewise with newspapers. We must be accurate, and we must be believed to be accurate. It’s a bitter pill to swallow, but we are failing on the second requirement. Most people believe the media is biased. Anyone who doesn’t see this is paying scant attention to reality, and those who fight reality lose. Reality is an undefeated champion. It would be easy to blame others for our long and continuing fall in credibility (and, therefore, decline in impact), but a victim mentality will not help. Complaining is not a strategy. We must work harder to control what we can control to increase our credibility.

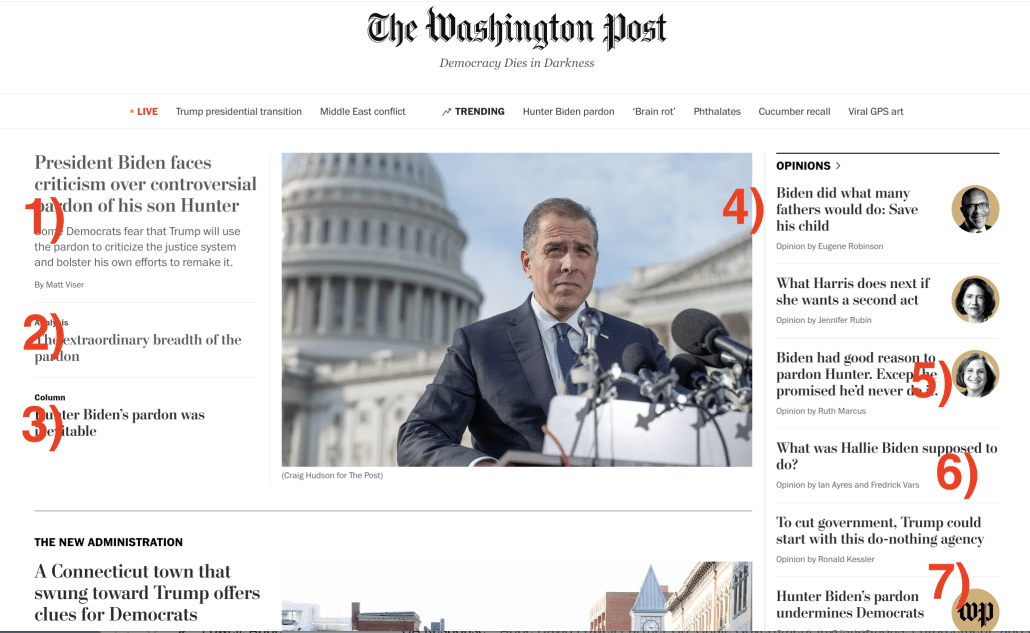

Weeks later, after sucking up to Trump post-election, Bezos’ rag buried news of the unfitness of Trump’s nominees behind 7 pieces on the Hunter Biden pardon.

The continued reliance on dick pic sniffing to convince right wingers the WaPo is not biased is particularly rich [cough] coming from Bezos, newly targeted by gossip from the Daily Mail picked up by NYP.

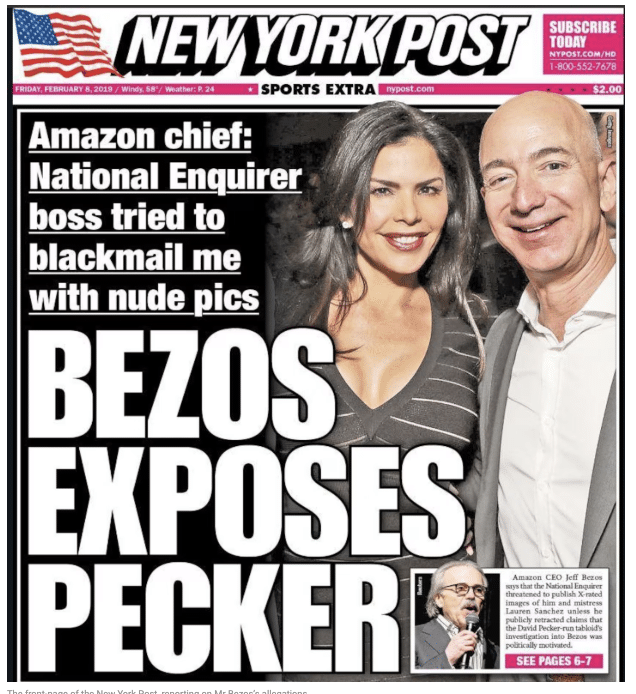

Bezos, of all people, should have known better than to exploit a guy targeted with revenge porn by hostile nation-states and political partisans. In 2019, the NY Enquirer, while under Non-Prosecution Agreement for its past Kill and Capture activities, tried to extort him with … dick pics. As a Dylan Howard email described when trying to get Bezos to call off an investigation into Saudi ties in all this, the rag that had intervened in 2016 to help elect Trump had ten damning pictures disclosing what was then an affair with Lauren Sanchez while Bezos was still married.

In addition to the “below the belt selfie — otherwise colloquially known as a ‘d*ck pick’” — The Enquirer obtained a further nine images. These include:

· Mr. Bezos face selfie at what appears to be a business meeting.

· Ms. Sanchez response — a photograph of her smoking a cigar in what appears to be a simulated oral sex scene.

· A shirtless Mr. Bezos holding his phone in his left hand — while wearing his wedding ring. He’s wearing either tight black cargo pants or shorts — and his semi-erect manhood is penetrating the zipper of said garment.

When Bezos preemptively exposed that effort (an effort that mysteriously didn’t turn into charges for a violation of National Enquirer’s past NPA), he attributed the attack to his ownership of the WaPo. But, the same guy spiking endorsements of Trump’s opponent and relying on dick pic sniffing to stave off claims of bias said then, his stewardship of the WaPo would remain unswerving.

Here’s a piece of context: My ownership of the Washington Post is a complexifier for me. It’s unavoidable that certain powerful people who experience Washington Post news coverage will wrongly conclude I am their enemy.

President Trump is one of those people, obvious by his many tweets. Also, The Post’s essential and unrelenting coverage of the murder of its columnist Jamal Khashoggi is undoubtedly unpopular in certain circles.

(Even though The Post is a complexifier for me, I do not at all regret my investment. The Post is a critical institution with a critical mission. My stewardship of The Post and my support of its mission, which will remain unswerving, is something I will be most proud of when I’m 90 and reviewing my life, if I’m lucky enough to live that long, regardless of any complexities it creates for me.)

It turns out, as happened the last time someone tried to start a scandal about Bezos’ relationship with Sanchez, the second richest man in the world didn’t have to rely on journalistic ethics to combat the dick pic sniffing.

Both the Daily Mail and the NYP prominently (including in a blurb added to the NYP video, above) added Bezos’ denial to their original stories.

Sources told the DailyMail.com that the billionaire Amazon founder, 60, and his ex-TV news anchor fiancée, 55, had bought out ritzy sushi restaurant Matsuhisa in the Colorado ski town for December 26 or 27, and have their nuptials planned for Saturday 28.

Three sources told DailyMail.com they had been made aware of the Bezos wedding taking place on December 28.

However, after the Daily Mail published the story, Bezos’s team, denied the wedding was going ahead next weekend.

The billionaire took to X on Sunday to slam the wedding claims as ‘completely false’.

‘This whole thing is completely false – none of this is happening,’ he posted on X. ‘The old adage “don’t believe everything you read” is even more true today than it ever has been.’

And by the time I returned to this exchange on Xitter, the link Ackman had RTed had been disabled, as if Xitter had [gasp!] throttled a link to a NYP story!

It didn’t even take the date of the alleged marriage passing for everyone to have cleaned up a story about the second richest man in the world!

Must be nice not to have to rely on corrections.

The problem is so, so much worse than an asymmetric relationship with the truth.

But it has a happy ending for defense contractor Jeff Bezos, whose Blue Origin rocket company was the most obvious hint of payback for his sycophancy, launched yesterday. Bezos posted rocket launch porn on his account at rival rocket man Elon’s site, and accepted the congratulations of numerous people, including his rocket man rival.

We are so beyond the stratosphere of symmetrical relationships to the truth.