How the Wyden/Khanna Espionage Act Fix Works (But Not for Julian Assange)

Last week, Ron Wyden and Ro Khanna released a bill that they say will eliminate much of the risk of prosecution that people without clearance would face under they Espionage Act. They claim the bill would limit the risk that:

- Whistleblowers won’t be able to share information with appropriate authorities

- Those appropriate authorities (including Congress) won’t be able to do anything with that information

- National security journalists will be prosecuted for publishing classified information

- Security researchers will be prosecuted for identifying and publishing vulnerabilities

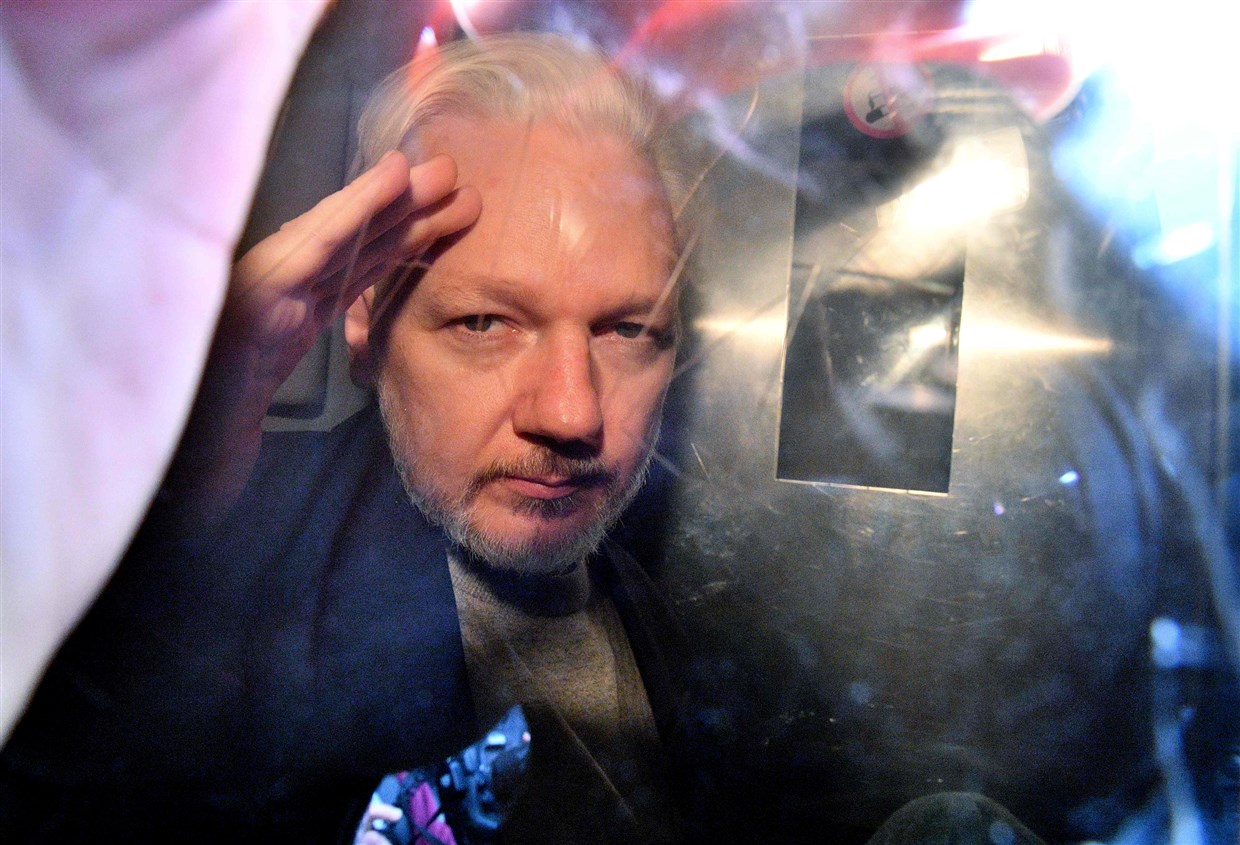

I want to look at how the bill would do that. But I want to do so against the background of claims about how the bill would affect the ability to prosecute Julian Assange.

After explaining that under the bill Edward Snowden could still be prosecuted, the summary of the bill states in no uncertain terms that the government could still prosecute Julian Assange under the bill.

Q: How would this bill impact the government’s prosecution of Julian Assange?

A: The government would still be able to prosecute Julian Assange.

It doesn’t say how, but immediately after that question, it explains that the government could still prosecute hackers who steal government secrets.

Q: What about hackers who break into government systems and steal our secrets?

A: The Espionage Act is not necessary to punish hackers who break into U.S. government systems. Congress included a special espionage offense (U.S.C § 1030(a)(1)) in the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, which specifically criminalizes this.

Khanna, in an interview with The Intercept, seems to confirm that explanation — that Assange could still be prosecuted under CFAA.

Khanna told The Intercept that the new bill wouldn’t stop the prosecution of Assange for his alleged role in hacking a government computer system, but would make it impossible for the government to use the Espionage Act to charge anyone solely for publishing classified information.

Indeed, that is sort of what Charge 18 against Assange is, conspiracy to commit computer intrusion, though, as written, it invokes the Espionage Act and theft of government secrets as part of the conspiracy (the Wyden/Khanna bill would limit the theft of government property bill in useful ways). Never mind that as charged it’s a weak charge for evidentiary reasons (though that may change in Assange’s May extradition hearing); it would still be available, if not provable given existing charged facts, under this bill.

But given the claims the US government makes about Assange, that may not be the only way he could be prosecuted under this bill. That’s because the bill works in two ways: first, by generally limiting its application to “covered persons,” who are people who’ve been authorized to access classified or national defense information by an Original Classification Authority. Then, it defines “foreign agent” using the definition in FISA (though carving out foreign political organizations) and says that anyone who is not a foreign agent “shall not be subject to prosecution” under the Espionage Act unless they commit a felony under the act — by aiding, abetting, or conspiring in the act — or pays for the information and wants to harm the US. The bill further carves out providing advice (for example, on operational security) or an electronic communication or remote computing service (such as a secure drop box) to the public.

So:

- If you don’t have clearance or are sharing information not obtained illegally or via your clearance and

- If you aren’t an agent of a foreign power and

- If you’re not otherwise paying for, conspiring or aiding and abetting in some way beyond offering operational security and drop boxes with the specific intent to harm the US or help another government

Then you shouldn’t be prosecuted under the Espionage Act.

Below, I’ve written up how 18 USC §793 and 18 USC §798 would change under the bill, with changes italicized (18 USC §794 already includes the foreign government language added by this bill so would not change).

In the wake of the 2016 election operation, where Julian Assange helped a Russian operation hiding behind thin denials, Assange might well meet the definition of “foreign agent.” Three of WikiLeaks’ operations — the Stratfor hack (in which Russians were involved in the chat rooms), the 2016 election year operation, and Vault 7 (in which Joshua Schulte, between the initial leak and the alleged attempts to leak from jail, evinced an interest in Russia’s help) — involved some Russian activity.

And it’s not clear how Congress’ resolution — passed in last year’s NDAA — that WikiLeaks is a non-state hostile intelligence service often abetted by state actors would affect Assange’s potential treatment as a foreign agent.

It is the sense of Congress that WikiLeaks and the senior leadership of WikiLeaks resemble a nonstate hostile intelligence service often abetted by state actors and should be treated as such a service by the United States.

But even with all the new protections for those who don’t have clearance, this bill specifically envisions applying it to someone like Assange. That’s because it explicitly incorporates aiding and abetting (18 USC § 2) — which is how Assange is currently charged in Counts 2-14 — as well as accessory after the fact (18 USC § 3), and misprison of a felony (18 USC § 4) into the bill. That’s on top of the conspiracy to commit an offense against the US (18 USC § 371), which is already implicitly incorporated in 18 USC § 793(g), which is Count 1 in the Assange indictment. Arguably, explicitly adding the accessory after the fact and misprison of a felony would make it easier to prosecute Assange for assistance that WikiLeaks and associated entities routinely provide sources after the fact, such as publicity and legal representation, to say nothing of the help that Sarah Harrison gave Edward Snowden to flee to Russia.

And those charges don’t require someone formally fit the definition of agent of a foreign power so long as the person has “the specific intent to harm the national security of the United States or benefit any foreign government to the detriment of the United States.” (I’ve bolded this language below.) That’s a mens rea requirement that might otherwise be hard to meet — but not in the case of Assange, even before you get into any non-public statements the US government might have in hand.

This is a bill from Ron Wyden, remember. Back in 2017, when he first spoke out when SSCI first moved to declare WikiLeaks a non-state hostile intelligence service, he expressed concerns about the lack of clarity in such a designation.

I have reservations about Section 623, which establishes a Sense of Congress that WikiLeaks and the senior leadership of WikiLeaks resemble a non-state hostile intelligence service. The Committee’s bill offers no definition of “non-state hostile intelligence service” to clarify what this term is and is not. Section 623 also directs the United States to treat WikiLeaks as such a service, without offering further clarity.

To be clear, I am no supporter of WikiLeaks, and believe that the organization and its leadership have done considerable harm to this country. This issue needs to be addressed. However, the ambiguity in the bill is dangerous because it fails to draw a bright line between WikiLeaks and legitimate journalistic organizations that play a vital role in our democracy.

I supported efforts to remove this language in Committee and look forward to working with my colleagues as the bill proceeds to address my concerns.

While this bill does much to protect journalists (and in a way that doesn’t create a special class for journalists or InfoSec researchers that would violate the First Amendment), it provides the clarity that would enable charging Assange, even for things he did after the fact to encourage leakers.

Update: Two more points on this. First, as I understand it, the explicit references to 18 USC §§ 2-4 are designed to protect reporters, meaning the protections apply to those as well.

I also meant to note that the way this bill is written — which is clearly meant to allow for prosecution of people working at state-owned media outlets (Russia, China, and Iran all use their outlets as cover for spies) — would then by design not protect reporters at the BBC or Al Jazeera, both of which have done reporting on stories implicating US classified information in the past.

18 USC § 793

(a) Whoever, for the purpose of obtaining information respecting the national defense with intent or reason to believe that the information is to be used to the injury of the United States, or to the advantage of any foreign nation, goes upon, enters, flies over, or otherwise unlawfully obtains nonpublic information concerning any vessel, aircraft, work of defense, navy yard, naval station, submarine base, fueling station, fort, battery, torpedo station, dockyard, canal, railroad, arsenal, camp, factory, mine, telegraph, telephone, wireless, or signal station, building, office, research laboratory or station or other place connected with the national defense owned or constructed, or in progress of construction by the United States or under the control of the United States, or of any of its officers, departments, or agencies, or within the exclusive jurisdiction of the United States, or any place in which any vessel, aircraft, arms, munitions, or other materials or instruments for use in time of war are being made, prepared, repaired, stored, or are the subject of research or development, under any contract or agreement with the United States, or any department or agency thereof, or with any person on behalf of the United States, or otherwise on behalf of the United States, or any prohibited place so designated by the President by proclamation in time of war or in case of national emergency in which anything for the use of the Army, Navy, or Air Force is being prepared or constructed or stored, information as to which prohibited place the President has determined would be prejudicial to the national defense; or

(b) An individual who, while a covered person, for the purpose aforesaid, and with like intent or reason to believe, copies, takes, makes, or obtains, or attempts to copy, take, make, or obtain, any sketch, photograph, photographic negative, blueprint, plan, map, model, instrument, appliance, document, writing, or note of anything connected with the national defense; or

(c) A foreign agent who, for the purpose aforesaid, and with like intent or reason to believe, receives or obtains or agrees or attempts to receive or obtain from any person, or from any source whatever, any document, writing, code book, signal book, sketch, photograph, photographic negative, blueprint, plan, map, model, instrument, appliance, or note, of anything connected with the national defense, knowing or having reason to believe, at the time the foreign agent receives or obtains, or agrees or attempts to receive or obtain it, that it has been or will be obtained, taken, made, or disposed of by any person contrary to the provisions of this chapter; or

(d) Whoever, lawfully having possession of, access to, control over, or being entrusted with any document, writing, code book, signal book, sketch, photograph, photographic negative, blueprint, plan, map, model, instrument, appliance, or note, or information relating to the national defense, which document, writing, code book, signal book, sketch, photograph, photographic negative, blueprint, plan, map, model, instrument, appliance, note, or information the possessor has reason to believe could be used to the injury of the United States or to the advantage of any foreign nation, willfully communicates, delivers, transmits or causes to be communicated, delivered, or transmitted or attempts to communicate, deliver, transmit or cause to be communicated, delivered or transmitted the same to any person not entitled to receive it, or willfully retains the same and fails to deliver it on demand to the officer or employee of the United States entitled to receive it; or

(e) An individual who—

(1) while a covered person, gains unauthorized possession of, access to, or control over any non public document, writing, code book, signal book, sketch, photograph, photographic negative, blueprint, plan, map, model, instrument, appliance, or note of anything connected with the national defense; and

(2)(A) with reason to believe such information could be used to the injury of the United States or to the advantage of any foreign nation, willfully communicates, delivers, transmits, or causes to be communicated, delivered, or transmitted, or attempts to communicate, deliver, transmit, or cause to be communicated, delivered, or transmitted, the same to any person not entitled to receive it; or

(B) willfully—

(i) retains the same at an unauthorized location; and

(ii) fails to deliver the same to the officer or employee of the United States entitled to receive it; or’

(f) Whoever, being entrusted with or having lawful possession or control of any document, writing, code book, signal book, sketch, photograph, photographic negative, blueprint, plan, map, model, instrument, appliance, (1) through gross negligence permits the same to be removed from its proper place of custody or delivered to anyone in violation of his trust, or to be lost, stolen, abstracted, or destroyed, or (2) having knowledge that the same has been illegally removed from its proper place of custody or delivered to anyone in violation of its trust, or lost, or stolen, abstracted, or destroyed, and fails to make prompt report of such loss, theft, abstraction, or destruction to his superior officer—

Shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than ten years, or both.

(g)(1) A foreign agent who—

(A) aids, abets, counsels, commands, induces, or procures the commission of an offense under this section shall be subject to prosecution under this section by virtue of section 2 of this title;

(B) knowing that an offense under this section has been committed by another person, receives, relieves, comforts, or assists such other person in order to hinder or prevent the apprehension, trial, or punishment of such other person shall be subject to prosecution under section 3 of this title;

(C) having knowledge of the actual commission of an offense under this section, conceals and does not as soon as possible make known the same to some judge or other person in civil or military authority under the United States shall be subject to prosecution under section 4 of this title; or

(D) conspires to commit an offense under this section shall be subject to prosecution under section 371 of this title.

(2) Any person who is not a foreign agent shall not be subject to prosecution under this section by virtue of section 2 of this title or under section 3, 4, or 371 of this 7 title, unless the person—

(A) commits a felony under Federal law in the course of committing an offense under this section (by virtue of section 2 of this title) or under section 3, 4, or 371 of this title;

(B) was a covered person at the time of the 13 offense; or

(C) subject to paragraph (3), directly and materially aids, or procures in exchange for anything of monetary value, the commission of an offense under this section with the specific intent to—

(i) harm the national security of the United States; or

(ii) benefit any foreign government to the detriment of the United States.

(3) Paragraph (2)(C) shall not apply to direct and material aid that consists of—

(A) counseling, education, or other speech activity; or

(B) providing an electronic communication service to the public or a remote computing service (as such terms are defined in section 2510 and 2711, respectively).

(h)

(1)Any person convicted of a violation of this section shall forfeit to the United States, irrespective of any provision of State law, any property constituting, or derived from, any proceeds the person obtained, directly or indirectly, from any foreign government, or any faction or party or military or naval force within a foreign country, whether recognized or unrecognized by the United States, as the result of such violation. For the purposes of this subsection, the term “State” includes a State of the United States, the District of Columbia, and any commonwealth, territory, or possession of the United States.

(2)The court, in imposing sentence on a defendant for a conviction of a violation of this section, shall order that the defendant forfeit to the United States all property described in paragraph (1) of this subsection.

(3)The provisions of subsections (b), (c), and (e) through (p) of section 413 of the Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act of 1970 (21 U.S.C. 853(b), (c), and (e)–(p)) shall apply to—

(A)property subject to forfeiture under this subsection;

(B)any seizure or disposition of such property; and

(C)any administrative or judicial proceeding in relation to such property, if not inconsistent with this subsection.

(4)Notwithstanding section 524(c) of title 28, there shall be deposited in the Crime Victims Fund in the Treasury all amounts from the forfeiture of property under this subsection remaining after the payment of expenses for forfeiture and sale authorized by law.

(i) In this section—

(1) the term “covered person” means an individual who—

(A) receives official access to classified information granted by the United States Government;

(B) signs a nondisclosure agreement with regard to such classified information; and

(C) is authorized to receive documents, writings, code books, signal books, sketches, photographs, photographic negatives, blueprints, plans, maps, models, instruments, appliances, or notes of anything connected with the national defense by—

(i) by the President; or

(ii) the head of a department or agency of the United States Government which is expressly designated by the President to engage in activities relating to the national defense; and

(2) the term “foreign agent”—

(A) has the meaning given the term “agent of a foreign power” under section 101 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act of 1978 (50 U.S.C. 1801); and

(B) does not include a person who is an agent of a foreign power (as so defined) with respect to a foreign power described in section 101(a)(5) of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act of 1978 (50 U.S.C. 1801(a)(5)).

18 USC §798

(a)Any individual who knowingly and willfully communicates, furnishes, transmits, or otherwise makes available to an unauthorized person, or publishes, or uses in any manner prejudicial to the safety or interest of the United States or for the benefit of any foreign government to the detriment of the United States any classified information obtained by the individual while the individual was a covered person and acting within the scope of his or her activities as a covered person—

(1) concerning the nature, preparation, or use of any code, cipher, or cryptographic system of the United States or any foreign government; or

(2) concerning the design, construction, use, maintenance, or repair of any device, apparatus, or appliance used or prepared or planned for use by the United States or any foreign government for cryptographic or communication intelligence purposes; or

(3) concerning the communication intelligence activities of the United States or any foreign government; or

(4) obtained by the processes of communication intelligence from the communications of any foreign government, knowing the same to have been obtained by such processes—

Shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than ten years, or both.

(b)As used in subsection (a) of this section:

(1) The term ‘classified information’—

(A) means information which, at the time of a violation of this section, is known to the person violating this section to be, for reasons of national security, specifically designated by a United States Government Agency for limited or restricted dissemination or distribution and;

(B) does not include any information that is specifically designated as ‘Unclassified’ under any Executive Order, Act of Congress, or action by a committee of Congress in accordance with the rules of its House of Congress.

(2) The terms ‘code’, ‘cipher’, and ‘cryptographic system’ include in their meanings, in addition to their usual meanings, any method of secret writing and any mechanical or electrical device or method used for the purpose of disguising or concealing the contents, significance, or meanings of communications.

(3) The term “communication intelligence” means all procedures and methods used in the interception of communications and the obtaining of information from such communications by other than the intended recipients.

(4) The term ‘covered person’ means an individual who—

(A) receives official access to classified information granted by the United States Government;

(B) signs a nondisclosure agreement with regard to such classified information; and

(C) is authorized to receive information of the categories set forth in subsection (a) of this section—

(i) by the President; or

(ii) the head of a department or agency of the United States Government which is expressly designated by the President to engage in communication intelligence activities for the United States

(5) The term “foreign government” includes in its meaning any person or persons acting or purporting to act for or on behalf of any faction, party, department, agency, bureau, or military force of or within a foreign country, or for or on behalf of any government or any person or persons purporting to act as a government within a foreign country, whether or not such government is recognized by the United States.

(6) The term “unauthorized person” means any person who, or agency which, is not authorized to receive information of the categories set forth in sub10 section (a) of this section by—

(A) the President;

(B) the head of a department or agency of the United States Government which is expressly designated by the President to engage in communication intelligence activities for the United States; or

(C) an Act of Congress.

(c)Nothing in this section shall prohibit the furnishing of information to—

(1) any Member of the Senate or the House of Representatives;

(2) a Federal court, in accordance with such procedures as the court may establish;

(3) the inspector general of an element of the intelligence community (as defined in section 3 of the National Security Act of 1947 (50 U.S.C. 3003)), including the Inspector General of the Intelligence Community;

(4) the Chairman or a member of the Privacy and Civil Liberties Oversight Board or any employee of the Board designated by the Board, in accordance with such procedures as the Board may establish;

(5) the Chairman or a commissioner of the Federal Trade Commission or any employee of the Commission designated by the Commission, in accordance with such procedures as the Commission may establish;

(6) the Chairman or a commissioner of the Federal Communications Commission or any employee of the Commission designated by the Com2 mission, in accordance with such procedures as the Commission may establish; or

(7) any other person or entity authorized to receive disclosures containing classified information pursuant to any applicable law, regulation, or executive order regarding the protection of whistleblowers.

(d)

(1) In this subsection, the term ‘foreign agent’—

(A) has the meaning given the term “agent of a foreign power” under section 101 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act of 1978 (50 U.S.C. 1801); and

(B) does not include a person who is an agent of a foreign power (as so defined) with respect to a foreign power described in section 101(a)(5) of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act of 1978 (50 U.S.C. 1801(a)(5)).

(2) A foreign agent who—

(A) aids, abets, counsels, commands, induces, or procures the commission of an offense under this section shall be subject to prosecution under this section by virtue of section 2 of this title;

(B) knowing that an offense under this section has been committed by another person, receives, relieves, comforts, or assists such other person in order to hinder or prevent the apprehension, trial, or punishment of such other person shall be subject to prosecution under section 3 of this title;

(C) having knowledge of the actual commission of an offense under this section, conceals and does not as soon as possible make known the same to some judge or other person in civil or military authority under the United States shall be subject to prosecution under section 4 of this title; or

(D) conspires to commit an offense under this section shall be subject to prosecution under section 371 of this title.

(3) Any person who is not a foreign agent shall not be subject to prosecution under this section by virtue of section 2 of this title or under section 3, 4, or 371 of this title, unless the person—

(A) commits a felony under Federal law in the course of committing an offense under this section (by virtue of section 2 of this title) or under section 3, 4, or 371 of this title;

(B) was a covered person at the time of the offense; or

(C) subject to paragraph (4), directly and materially aids, or procures in exchange for anything of monetary value, the commission of an offense under this section with the specific intent to—

(i) harm the national security of the United States; or

(ii) benefit any foreign government to the detriment of the United States.

(4) Paragraph (3)(C) shall not apply to direct and material aid that consists of—

(A) counseling, education, or other speech activity; or

(B) providing an electronic communication service to the public or a remote computing service (as such terms are defined in section 2510 and 2711, respectively)

(e)

(1)Any person convicted of a violation of this section shall forfeit to the United States irrespective of any provision of State law—

(A)any property constituting, or derived from, any proceeds the person obtained, directly or indirectly, as the result of such violation; and

(B)any of the person’s property used, or intended to be used, in any manner or part, to commit, or to facilitate the commission of, such violation.

(2)The court, in imposing sentence on a defendant for a conviction of a violation of this section, shall order that the defendant forfeit to the United States all property described in paragraph (1).

(3)Except as provided in paragraph (4), the provisions of subsections (b), (c), and (e) through (p) of section 413 of the Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act of 1970 (21 U.S.C. 853(b), (c), and (e)–(p)), shall apply to

(A)property subject to forfeiture under this subsection;

(B)any seizure or disposition of such property; and

(C)any administrative or judicial proceeding in relation to such property,

if not inconsistent with this subsection.

(4)Notwithstanding section 524(c) of title 28, there shall be deposited in the Crime Victims Fund established under section 1402 of the Victims of Crime Act of 1984 (42 U.S.C. 10601) [1] all amounts from the forfeiture of property under this subsection remaining after the payment of expenses for forfeiture and sale authorized by law.

(5)As used in this subsection, the term “State” means any State of the United States, the District of Columbia, the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, and any territory or possession of the United States.