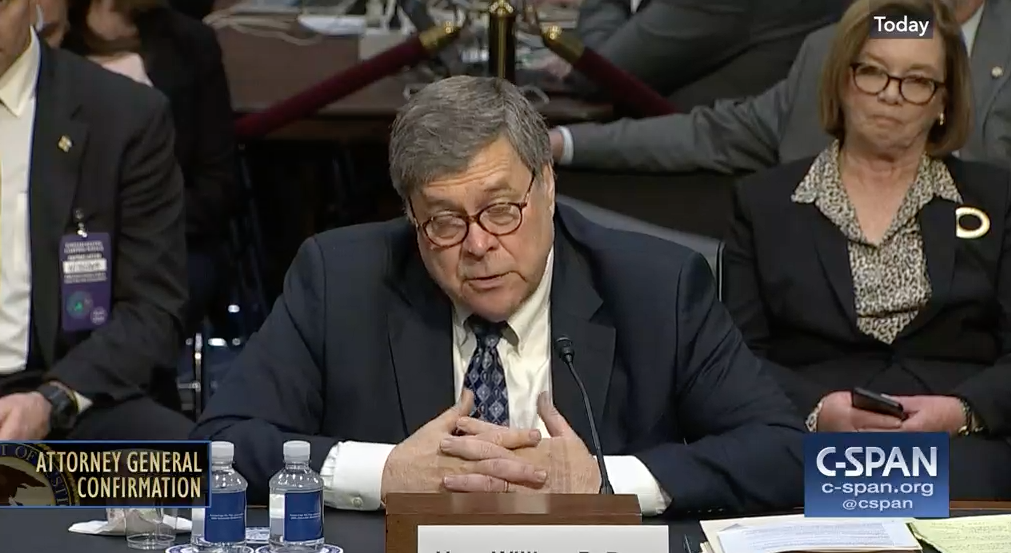

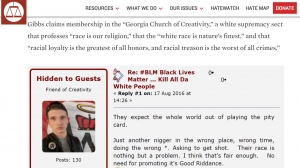

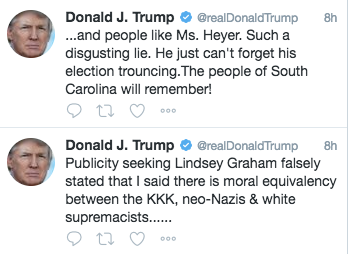

As pointed out first by Nick Watson in the Gainesville (Georgia) Times and then fleshed out further by Chris Joyner in the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, US District Judge Richard Story on September 21 dismissed a charge of possession of the deadly poison ricin against William Christopher Gibbs. Gibbs had been identified after his arrest by the Southern Poverty Law Center’s Hatewatch as a member of the bizarre Georgia Church of Creativity:

As pointed out first by Nick Watson in the Gainesville (Georgia) Times and then fleshed out further by Chris Joyner in the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, US District Judge Richard Story on September 21 dismissed a charge of possession of the deadly poison ricin against William Christopher Gibbs. Gibbs had been identified after his arrest by the Southern Poverty Law Center’s Hatewatch as a member of the bizarre Georgia Church of Creativity:

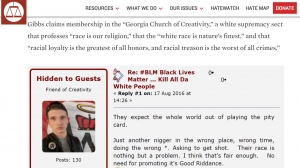

Gibbs claims membership in the “Georgia Church of Creativity,” a white supremacy sect that professes “race is our religion,” that the “white race is nature’s finest,” and that “racial loyalty is the greatest of all honors, and racial treason is the worst of all crimes.”

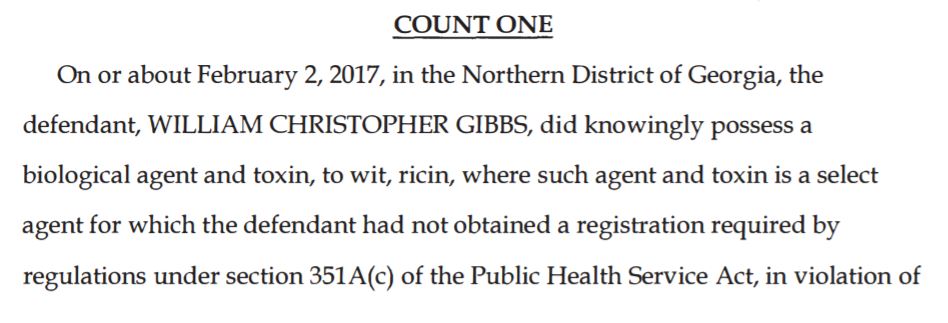

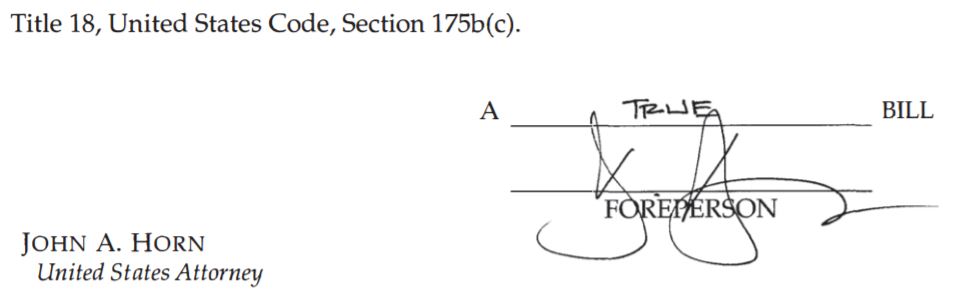

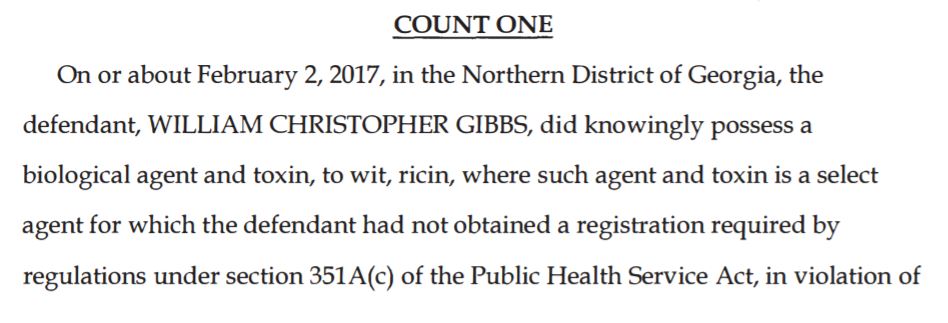

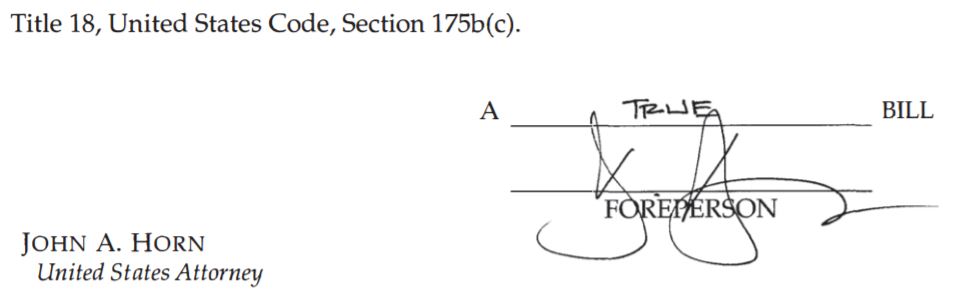

In his indictment, Gibbs was charged by a grand jury:

In his order directing that the charge be dismissed, Judge Story frames his decision as being due to a mere “clerical error” by the government in drawing up the underlying law and fleshing out the details in subsequent publication of rules. As Joyner described it:

A north Georgia white supremacist arrested last year for alleged possession of the deadly toxin ricin is no longer facing federal charges after a judge dismissed the case — on a technicality that exposes a regulatory failure.

In an order signed Sept. 21, U.S. District Court Judge Richard Story agreed with the man’s legal team that changes to federal law in 2004 and regulatory edits in 2005 inexplicably excluded ricin from the criminal charge of possession of illegal biological toxins known as “select agents.”

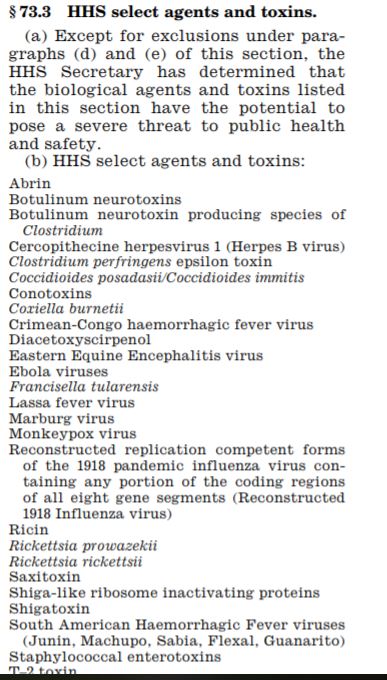

The huge problem here is that ricin is not the only agent that now, due to this error, falls outside the list of those proscribed from possession. Congress delegates the development and maintenance of the list of “select agents” to which this law applies to the Department of Health and Human Service for those agents that are human pathogens or toxins and to USDA for those agents that affect livestock or crops. The law also recognizes that some agents on these two lists will overlap, posing threats both to human and agricultural targets.

As Story details in his order, Congress revised the underlying law in late 2004. The list of select agents at that time showed clearly that ricin fell squarely within the purview of the law. But just a few months later, in early 2005, HHS revised its list and in this process, the entire non-overlapping list of human agents suddenly moved to a differently numbered section as it was published. That section number is not listed in the language in the 2004 revision, and so in ruling that Gibbs did not violate the law in possessing ricin, he is in effect making the entire HHS non-overlapping list exempt from the law. That means that under his interpretation, possessing the worst of the worst of the human pathogens or toxins, including even smallpox, cannot be charged under this law.

Here is the language of 18 US Code§ 175b(c), the section cited by the grand jury in the Gibbs indictment:

(c)UNREGISTERED FOR POSSESSION.—

(1)SELECT AGENTS.—

Whoever knowingly possesses a biological agent or toxin where such agent or toxin is a select agent for which such person has not obtained a registration required by regulations under section 351A(c) of the Public Health Service Act shall be fined under this title, or imprisoned for not more than 5 years, or both.

(2)CERTAIN OTHER BIOLOGICAL AGENTS AND TOXINS.—

Whoever knowingly possesses a biological agent or toxin where such agent or toxin is a biological agent or toxin listed pursuant to section 212(a)(1) of the Agricultural Bioterrorism Protection Act of 2002 for which such person has not obtained a registration required by regulations under section 212(c) of such Act shall be fined under this title, or imprisoned for not more than 5 years, or both.

This part of the law was from the 2004 revision we discussed earlier. In his decision, Story notes that the reading of the whole of

18 US Code§ 175b directs us to the first part of it to find where the list of select agents can be found. It reads:

(a)

(1)

No restricted person shall ship or transport in or affecting interstate or foreign commerce, or possess in or affecting interstate or foreign commerce, any biological agent or toxin, or receive any biological agent or toxin that has been shipped or transported in interstate or foreign commerce, if the biological agent or toxin is listed as a non-overlap or overlap select biological agent or toxin in sections 73.4 and 73.5 of title 42, Code of Federal Regulations, pursuant to section 351A of the Public Health Service Act, and is not excluded under sections 73.4 and 73.5 or exempted under section 73.6 of title 42, Code of Federal Regulations.

(2)

Whoever knowingly violates this section shall be fined as provided in this title, imprisoned not more than 10 years, or both, but the prohibition contained in this section shall not apply with respect to any duly authorized United States governmental activity.

The problem is when we move to the current version of these lists, found

here, the numbering for the sections is off when we look at the lists, we see that the entire HHS non-overlapping list is found in section 73.3 and not in 73.4 or 73.5. The agents found in 73.3 are the worst of the worst of agents feared as biological weapons. Even smallpox is on that part of the list, and so, by Story’s ruling, now excluded from prosecution.

In his order, Story relies on this garbled numbering to dismiss the charge:

As described above, § 175b defines “select agent,” as a “biological agent

or toxin” that is listed in 42 C.F.R. § 73.4 or § 73.5. This language is

unambiguous. And in defining “select agent,” the statute does not reference a

non-exhaustive list or provide examples; rather, it says what the term “means.”

42 U.S.C. § 175b(d)(l) (emphasis added). ‘”[M]eans’ denotes an exhaustive

defmition[.]” StanselL 704 F.3d at 915 filth Cir. 2013) (citing United States v.

Probel. 214 F.3d 1285, 1288-89 (11th Cir.2000)). Thus, “[w]hen a statutory

definition declares what a term ‘means’ rather than ‘includes/ any meaning not

stated is excluded.” Id, (citing Colautti v. Franklin, 439 U.S. 379, 392-93 &

n. 10 (1979)). Here, neither 42 C.F.R. § 73.4 nor § 73.5 include ricin. The

statute does not reference-and thereby excludes-any other sections of the

C.F.R. So, applying the statutory definition, as the Court is bound to do, the

unavoidable conclusion is that “select agent” under 18 U.S.C. § 175b does not

include ricin.2

Story even knows how the garbled numbering came about:

In 2004, as part of the Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention

Act, Congress changed the reference from “Appendix A of part 72” to Part 73.

Pub. L. 108-458, 118 Stat. 3638, § 6802(d). This had the effect of

criminalizing the possession of “a non-overlap or overlap select biological

agent or toxin in sections 73.4 and 73.5 of Title 42” of the C.F.R. However,

three months later, HHS re-formatted its regulations, which, in relevant part,

resulted in its list of select agents and toxins-including ricin-being moved to a

section of the C.F.R. (§ 73.3) that is not referenced in 18 U.S.C. § 175b.

Story’s ruling is technically correct and is a defense attorney’s dream. But his justification of it is infuriating:

After HHS overhauled its regulatory numbering scheme, Congress had ample opportunity

to amend the statute to make its definition of “select agent” comport to the

Government’s interpretation. It has been 14 years, and Congress is yet to do

so. And there are plausible explanations why. For instance, Congress may

have decided that the unregistered possession of ricin, alone, is not conduct

sufficiently culpable to justify the commission of a federal crime. Or, Congress

may have assumed that the illegality of having certain biological agents and

toxins, like ricin, for nefarious purposes is sufficiently encapsulated in other

statutory provisions. See 18 U.S.C. § 175. The Court cannot say, but it is not

for the Court to disregard a clear statutory definition in favor of absent

language that may or may not have been excluded purposefully.

We are not talking here about a single agent, ricin, being left off the list due to a clerical error. The renumbering left the entire HHS non-overlapping list of agents out of the referenced sections. How on earth could Story believe that Congress would suddenly decide, in early 2005, that the entire HHS non-overlapping list was no longer of concern? Granted, anthrax is on the overlap list and so is still covered under Story’s interpretation, but it should be pointed out that the

Amerithrax investigation of the 2001 anthrax attacks was in full gear in 2005 in its march toward hounding Bruce Ivins to his death, so bioterror was a very high priority for Congress and law enforcement at the time of this reclassification. In fact, the boondoggle

BioWatch program was launched in 2003 and so in 2005, the generalized fear of bioweapons was pervasive. Also, don’t forget the role of bioweapons in general in the Bush Administration run-up to the invasion of Iraq in 2003, complete with Colin Powell’s fake vial of anthrax.

Further evidence of the government’s intent on the select agent list can be found when one looks for the list itself. For example,

this listing clearly shows the government had no intent to exclude the HHS non-overlapping agents and cites relevant statutory authority.

Story attempts, in part, to wriggle out of the deep hole into which he has dug himself by pointing out other ways that Gibbs could be charged. From a footnote in the order:

2 The Court notes, however, that the possession of ricin is not a wholly legal

endeavor. To the contrary, 18 U.S.C. § 175(a) provides:

Whoever knowingly develops, produces, stockpiles, transfers, acquires,

retains, or possesses any biological agent, toxin, or delivery system for

use as a weapon,… or attempts, threatens, or conspires to do the same,

shall be fined under this title or imprisoned for life or any term of years,

or both.

In assessing the constitutionality of this provision under the vagueness doctrine, the

Eleventh Circuit held, “The statute provides a person of ordinary intelligence with fair

warning that possessing castor beans, while knowing how to extract ricin, a biological

toxin, from the beans, and intending to use the ricin as a weapon to kill people, is

prohibited.” United States v. Crump, 609 F. App’x 621, 622 (11th Cir. 2015) (citing

United States v. Lebowitz, 676 F.3 d 1000, 1012 (llth Cir.2012) (per curiam)).

Interestingly, when I went back to look at one of my posts on James Everett Dutschke, who was charged with possessing ricin in Mississippi in 2013, I see that he was indeed charged under 18 U.S.C. § 175(a).

The damage that Story has done in this ruling may not be limited solely to the HHS non-overlapping agents being left out of the law. Another aspect of the garbled re-numbering of sections is that § 73.5 is referenced as a list of proscribed agents. In reality, the section is headed “Exemptions for HHS select agents and toxins”. I would argue that this is further evidence of a simple error and not legislative intent, because it renders the bill unintelligible. Instead of a list of banned agents, it is a list of those that are exempt from the law due to their use in laboratories for diagnosis or research. Although Story does make passing reference to the differences among those agents that are on the list to be banned, those that are excluded and those that are exempt, I fear that opponents of biological research could latch onto Story’s ruling in an attempt to argue that shipment of these research or diagnostic samples could be prosecuted as bioterrorism. That could have a chilling impact on research to protect us from these very agents.

Congress clearly needs to fix this mess, and fix it quickly. Simple language adjustment in 18 US Code§ 175b(a)(1) could restore the law to applying to the proper lists of agents while excluding or exempting those for which it is appropriate.