First They Came for James Risen …

I don’t mean to suggest the journalism world did not object to the three subpoenas James Risen got in the Jeffrey Sterling case. They did.

But today’s news that Fox’s James Rosen was accused of being an “Aider or Abettor” to Stephen Jin-Woo Kim’s alleged crime of leaking information on Korea is just part of a progression. (See also WaPo’s story which broke this.)

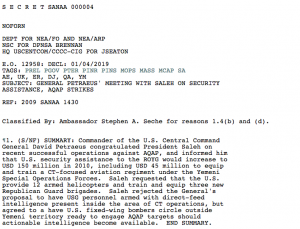

“I believe there is probable cause to conclude that the contents of the wire and electronic communications pertaining to the SUBJECT ACCOUNT [the gmail account of Mr. Rosen] are evidence, fruits and instrumentalities of criminal violations of 18 U.S.C. 793 (Unauthorized Disclosure of National Defense Information), and that there is probable cause to believe that the Reporter has committed or is committing a violation of section 793(d), as an aider and abettor and/or co-conspirator, to which the materials relate,” wrote FBI agent Reginald B. Reyes in a May 28, 2010 application for a search warrant.

The search warrant was issued in the course of an investigation into a suspected leak of classified information allegedly committed by Stephen Jin-Woo Kim, a former State Department contractor, who was indicted in August 2010.

The Reyes affidavit all but eliminates the traditional distinction in classified leak investigations between sources, who are bound by a non-disclosure agreement, and reporters, who are protected by the First Amendment as long as they do not commit a crime.

[snip]

As evidence of Mr. Rosen’s purported culpability, the Reyes affidavit notes that Rosen and Kim used aliases in their communications (Kim was “Leo” and Rosen was “Alex”) and in other ways sought to maintain confidentiality.

“From the beginning of their relationship, the Reporter asked, solicited and encouraged Mr. Kim to disclose sensitive United States internal documents and intelligence information…. The Reporter did so by employing flattery and playing to Mr. Kim’s vanity and ego.”

“Much like an intelligence officer would run an [sic] clandestine intelligence source, the Reporter instructed Mr. Kim on a covert communications plan… to facilitate communication with Mr. Kim and perhaps other sources of information.”

After all, in January 2011 (which was actually after this affidavit, but appeared 10 months before this affidavit was unsealed), DOJ argued that when Jeffrey Sterling leaked information to James Risen about a dangerous plot to deal nuke blueprints to Iran, his actions were worse than what DOJ called “typical espionage.”

The defendant’s unauthorized disclosures, however, may be viewed as more pernicious than the typical espionage case where a spy sells classified information for money. Unlike the typical espionage case where a single foreign country or intelligence agency may be the beneficiary of the unauthorized disclosure of classified information, this defendant elected to disclose the classified information publicly through the mass media. Thus, every foreign adversary stood to benefit from the defendant’s unauthorized disclosure of classified information, thus posing an even greater threat to society.

Then, in March 2011, DOD charged Bradley Manning with aiding the enemy because he leaked a bunch of stuff to us.

In other words, during a period from May 2010 through January 2011, Eric Holder’s DOJ was developing this theory under which journalists were criminals, though it’s just now that we’re all noticing this May 2010 affidavit that lays the groundwork for that theory.

Maybe that development was predictable, given that during precisely that time period, the lawyer who fucked up the Ted Stevens prosecution, William Welch, was in charge of prosecuting leaks (though it’s not clear he had a role in Kim’s prosecution before he left in 2011).

But it’s worth noting the strategy — and the purpose it serves — because it is almost certainly still in effect. FBI Special Agent Reginald Reyes accused Rosen of being a criminal so he could get around the Privacy Protection Act protections for media work product (See pages 4 and following), which specifically exempts “fruits of a crime” or “property … used [] as a means of committing a criminal offense.” Then he further used it to argue against giving notice to Fox or Rosen.

Because of the Reporter’s own potential criminal liability in this matter, we believe that requesting the voluntary production of the materials from Reporter would be futile and would pose a substantial threat to the integrity of the investigation and of the evidence we seek to obtain by the warrant. (29)

While the AP’s phone records weren’t taken via a warrant, it would be unsurprising if the government is still using this formula — journalists = criminals and therefore cannot have notice — to collect evidence. Indeed, that may be one reason why we haven’t seen the subpoena to the AP.

Of course, this is not just about journalists. In this schema, providing information about what our government is doing in our name to citizens constitutes a crime.

This criminalization of journalism is a fundamentally anti-democratic stance.