I’ve finally finished reading the set of 702 documents I Con the Record dumped a few weeks back. I did two posts on the dump and a related document Charlie Savage liberated. Both pertain, generally, to whether a 702 “selector” gets defined in a way that permits US person data to be sucked up as well. The first post reveals that, in 2010, the government tried to define a specific target under 702 (both AQAP and WikiLeaks might make sense given the timing) as including US persons. John Bates asked for legal justification for that, and the government withdrew its request.

The second reveals that, in 2011, as Bates was working through the mess of upstream surveillance, he asked whether the definition of “active user,” as it applies for a multiple communication transaction, referred to the individual user. The question is important because if a facility is defined to be used by a group — say, Al Qaeda or Wikileaks — it’s possible a user of that facility might be an unknown US person user, the communications of which would only be segregated under the new minimization procedures if the individual user’s communication were reviewed (not that it mattered in the end; NSA doesn’t appear to have implemented the segregation regime in meaningful fashion). Bates never got a public answer to that question, which is one of a number of reasons why Rosemary Collyer’s April 26 702 opinion may not solve the problem of upstream collection, especially not with back door searches permitted.

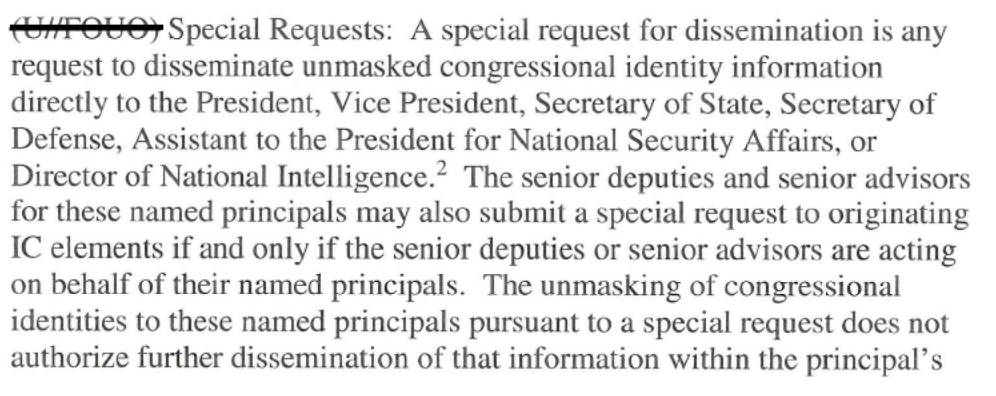

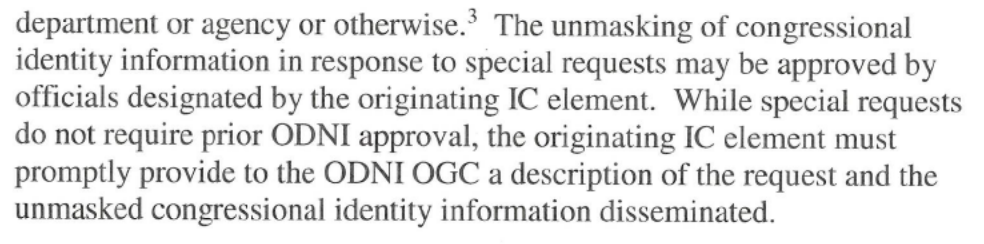

As it happens, some of the most important documents released in the dump may pertain to a closely related issue: whether the government can collect on selectors it knows may be used by US persons, only to weed out the US persons after the fact.

In 2014, a provider challenged orders (individual “Directives” listing account identifiers NSA wanted to collect) that it said would amount to conducting surveillance “on the servers of a U.S.-based provider” in which “the communications of U.S. persons will be collected as part of such surveillance.” The provider was prohibited from reading the opinions that set the precedent permitting this kind of collection. Unsurprisingly, the provider lost its challenge, so we should assume that some 702 collection collects US person communications, using the post-tasking process rather than pre-targeting intelligence to protect American privacy.

The documents

The documents that lay out the failed challenge are:

2014, redacted date: ACLU Document 420: The government response to the provider’s filing supporting its demand that FISC mandate compliance.

2014, redacted date: EFF Document 13: The provider(s) challenging the Directives asked for access to two opinions the government relied on in their argument. Rosemary Collyer refused to provide them, though they have since been released.

2014, redacted date: EFF Document 6 (ACLU 510): Unsurprisingly, Collyer also rejected the challenge to the individual Directives, finding that post-tasking analysis could adequately protect Americans.

The two opinions the providers requested, but were refused, are:

September 4, 2008 opinion: This opinion, by Mary McLaughlin, was the first approval of FAA certifications after passage of the law. It lays out many of the initial standards that would be used with FAA (which changed slightly from PAA). As part of that, McLaughin adopted standards regarding what kinds of US person collection would be subject to the minimization procedures.

August 26, 2014 opinion: This opinion, by Thomas Hogan, approved the certificates under which the providers had received Directives (which means the challenge took place between August and the end of 2014). But the government also probably relied on this opinion for a change Hogan had just approved, permitting NSA to remain tasked on a selector even if US persons also used the selector.

The argument also relies on the October 3, 2011 John Bates FAA opinion and the August 22, 2008 FISCR opinion denying Yahoo’s challenge to Protect America Act. The latter was released in a second, less redacted form on September 11, 2014, which means the challenge likely post-dated that release.

The government’s response

The government’s response consists of a filing by Stuart Evans (who has become DOJ’s go-to 702 hawk) as well as a declaration submitted by someone in NSA that had already reviewed some of the taskings done under the 2014 certificates (which again suggests this challenge must date to September at the earliest). There appear to be four sections to Evans’ response. Of those sections, the only one left substantially unredacted — as well as the bulk of the SIGINT declaration — pertains to the Targeting Procedures. So while targeting isn’t the only thing the provider challenged (another appears to be certification of foreign intelligence value), it appears to be the primary thing.

Much of what is unredacted reviews the public details of NSA’s targeting procedure. Analysts have to use the totality of circumstances to figure out whether someone is a non US person located overseas likely to have foreign intelligence value, relying on things like other SIGINT, HUMINT, and (though the opinion redacts this) geolocation information and/or filters to weed out known US IPs. After a facility has been targeted, the analyst is required to do post-task analysis, both to make sure that the selector is the one intended, but also to make sure that no new information identifies the selector as being used by a US person, as well as making sure that the target hasn’t “roamed” into the US. Post-task analysis also ensures that the selector really is providing foreign intelligence information (though in practice, per PCLOB and other sources, this is not closely reviewed).

Of particular importance, Evans dismisses concerns about what happens when a selector gets incorrectly tasked as a foreigner. “That such a determination may later prove to be incorrect because of changes in circumstances or information of which the government was unaware does not render unreasonable either the initial targeting determination or the procedures used to reach it.”

Evans also dismisses the concern that minimization procedures don’t protect the providers’ customers (presumably because they provide four ways US person content may be retained with DIRNSA approval). Relying on the 2008 opinion that states in part…

The government argues that, by its terms, Section 1806(i) applies only to a communication that is unintentionally acquired,” not to a communication that is intentionally acquired under a mistaken belief about the location or non-U.S. person status of the target or the location of the parties to the communication. See Government’s filing of August 28, 2008. The Court finds this analysis of Section 1806(i) persuasive, and on this basis concludes that Section 1806(i) does not require the destruction of the types of communications that are addressed by the special retention provisions.”

Evans then quotes McClaughlin judging that minimization procedures “constitute a safeguard against improper use of information about U.S. persons that is inadvertently or incidentally acquired.” In other words, he cites an opinion that permits the government to treat stuff that is initially targeted, even if it is later discovered to be an American’s communication, differently than it does other US person information as proof the minimization procedures are adequate.

The missing 2014 opinion references

As noted above, the provider challenging these Directives asked for both the 2008 opinion (cited liberally throughout the unredacted discussion in the government’s reply) and the 2014 one, which barely appears at all beyond the initial citation. Given that Collyer reviewed substantial language from both opinions in denying the provider’s request to obtain them, the discussion must go beyond simply noting that the 2014 opinion governs the Directives in question. There must be something in the 2014 opinion, probably the targeting procedures, that gets cited in the vast swaths of redactions.

That’s especially true given that on the first page of Evans’ response claims the Directives address “a critical, ongoing foreign intelligence gap.” So it makes sense that the government would get some new practice approved in that year’s certification process, then serve Directives ostensibly authorized by the new certificate, only to have a provider challenge a new type of request and/or a new kind of provider challenge their first Directives.

One thing stands out in the 2014 opinion that might indicate the closing of a foreign intelligence gap.

Prior to 2014, the NSA could say an entity — say, Al Qaeda — used a facility, meaning they’d suck up any people that used that facility (think how useful it would be to declare a chat room a facility, for example). But (again, prior to 2014) as soon as a US person started “using” that facility — the word use here is squishy as someone talking to the target would not count as “using” it, but as incidental collection — then NSA would have to detask.

The 2014 certifications for the first time changed that.

The first revision to the NSA Targeting Procedures concerns who will be regarded as a “target” of acquisition or a “user” of a tasked facility for purposes of those procedures. As a general rule, and without exception under the NSA targeting procedures now in effect, any user of a tasked facility is regarded as a person targeted for acquisition. This approach has sometimes resulted in NSA’ s becoming obligated to detask a selector when it learns that [redacted]

The relevant revision would permit continued acquisition for such a facility.

[snip]

For purposes of electronic surveillance conducted under 50 U.S.C. §§ 1804-1805, the “target” of the surveillance ‘”is the individual or entity … about whom or from whom information is sought.”‘ In re Sealed Case, 310 F.3d 717, 740 (FISA Ct. Rev. 2002) (quoting H.R. Rep. 95-1283, at 73 (1978)). As the FISC has previously observed, “[t]here is no reason to think that a different meaning should apply” under Section 702. September 4, 2008 Memorandum Opinion at 18 n.16. It is evident that the Section 702 collection on a particular facility does not seek information from or about [redacted].

In other words, for the first time in 2014, the FISC bought off on letting the NSA target “facilities” that were used by a target as well as possibly innocent Americans, based on the assumption that the NSA would weed out the Americans in the post-tasking process, and anyway, Hogan figured, the NSA was unlikely to read that US person data because that’s not what they were interested in anyway.

Mind you, in his opinion approving the practice, Hogan included a bunch of mostly redacted language pretending to narrow the application of this language.

This amended provision might be read literally to apply where [redacted]

But those circumstances fall outside the accepted rationale for this amendment. The provision should be understood to apply only where [redacted]

But Hogan appears to be policing this limiting language by relying on the “rationale” of the approval, not any legal distinction.

The description of this change to tasking also appears in a 3.5 page discussion as the first item in the tasking discussion in the government’s 2014 application, which Collyer would attach to her opinion.

Collyer’s opinion

Collyer’s opinion includes more of the provider’s arguments than the Reply did. It describes the Directives as involving “surveillance conducted on the servers of a U.S.-based provider” in which “the communications of U.S. person will be collected as part of such surveillance.” (29) It says [in Collyer’s words] that the provider “believes that the government will unreasonably intrude on the privacy interests of United States persons and persons in the United States [redacted] because the government will regularly acquire, store, and use their private communications and related information without a foreign intelligence or law enforcement justification.” (32-3) It notes that the provider argued there would be “a heightened risk of error” in tasking its customers. (12) The provider argued something about the targeting and minimization procedures “render[ed] the directives invalid as applied to its service.” (16) The provider also raised concerns that because the NSA “minimization procedures [] do not require the government to immediately delete such information[, they] do not adequately protect United States person.” (26)

All of which suggests the provider believed that significant US person data would be collected off their servers without any requirement the US person data get deleted right away. And something about this provider’s customers put them at heightened risk of such collection, beyond (for example) regular upstream surveillance, which was already public by the time of this challenge.

Collyer, too, says a few interesting things about the proposed surveillance. For example, she refers to a selector as an “electronic communications account” as distinct from an email — a rare public admission from the FISC that 702 targets things beyond just emails. And she treats these Directives as an “expansion of 702 acquisitions” to some new provider or technology. Finally, Collyer explains that “the 2014 Directives are identical, except for each directive referencing the particular certification under which the directive is issued.” This means that the provider received more than one Directive, and they fall under more than one certificate, which means that the collection is being used for more than one kind of use (counterterrorism, counterproliferation, and foreign government plus cyber). So the provider is used by some combination of terrorists, proliferators, spies, or hackers.

Ultimately, though, Collyer rejected the challenge, finding the targeting and minimization procedures to be adequate protection of the US person data collected via this new approach.

Now, it is not certain that all this relied on the new targeting procedure. Little in Collyer’s language reflects passing familiarity with that new provision. Indeed, at one point she described the risk to US persons to involve “the government may mistakenly task the wrong account,” which suggests a more individualized impact.

Except that after her almost five pages entirely redacted of discussion of the provider’s claim that the targeting procedures are insufficient, Collyer argues that such issues don’t arise that frequently, and even if they do, they’d be dealt with in post-targeting analysis.

The Court is not convinced that [redacted] under any of the above-described circumstances occurs frequently, or even on a regular basis. Assuming arguendo that such scenarios will nonetheless occur with regard to selectors tasked under the 2014 Directives, the targeting procedures address each of the scenarios by requiring NSA to conduct post-targeting analysis [redacted]

Similarly, Collyer dismissed the likelihood that Americans’ data would be tasked that often.

[O]ne would not expect a large number of communications acquired under such circumstances to involve United States person [citation to a redacted footnote omitted]. Moreover, a substantial proportion of the United States person communications acquired under such circumstances are likely to be of foreign intelligence value.

As she did in her recent shitty opinion, Collyer appears to have made these determinations without requiring NSA to provide real numbers on past frequency or likely future frequency.

However often such collection had happened in the past (which she didn’t ask the NSA to explain) or would happen as this new provider started responding to Directives, this language does sound like it might implicate the new case of a selector that might be used both by legitimate foreign intelligence targets and by innocent Americans.

Does the government use 702 collection to obtain VPN traffic?

As I noted, it seems likely, though not certain, that the new collection exploited the new permission to keep tasking a selector even if US persons were using it, in addition to the actual foreigners targeted. I’m still trying to puzzle this through, but I’m wondering if the provider was a VPN provider, being asked to hand over data as it passed through the VPN server. (I think the application approved in 2014 would implicate Tor traffic as well, but I can’t see how a Tor provider would challenge the Directives, unless it was Nick Merrill again; in any case, there’d be no discussion of an “account” with Tor in the way Collyer uses it).

What does this mean for upstream surveillance

In any case, whether my guesstimates about what this is are correct, the description of the 2014 change and the discussion about the challenge would seem to raise very important questions given Collyer’s recent decision to expand the searching of upstream collection. While the description of collection from a provider’s server is not upstream, it would seem to raise the same problems, the collection of a great deal of associated US person collection that could later be brought up in a search. There’s no hint in any of the public opinions that such problems were considered.

![[Photo: National Security Agency via Wikimedia]](https://www.emptywheel.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/NationalSecurityAgency_2013_Wikimedia.jpg)

![[Photo: National Security Agency, Ft. Meade, MD via Wikimedia]](https://www.emptywheel.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/NationalSecurityAgency_HQ-FortMeadeMD_Wikimedia.jpg)