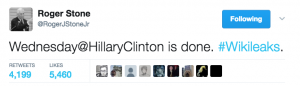

Both the Wikileaks Podesta release and the Access Hollywood tape drowned out the Intelligence Community report on Russia

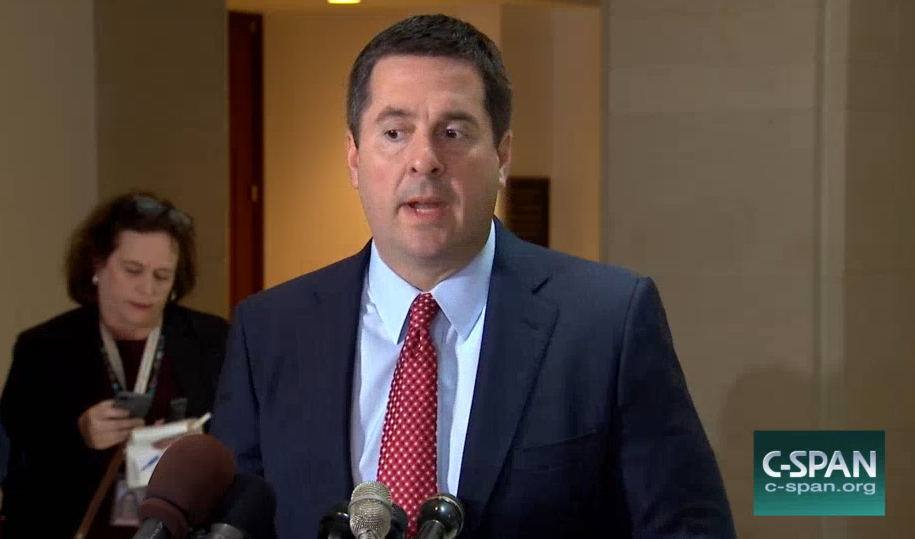

Earlier this week, in an interview with Politico (the story and the interview transcript seem to be memory holed for now), Obama’s Homeland Security Czar Lisa Monaco insisted that the Obama response to the Russian hack of the DNC was actually quite forceful, but that it got lost in the release of the Access Hollywood video showing Trump threatening to grab women by the pussy.

But strong supporters of Clinton’s campaign argued—some at the time, many more in the wake of the former secretary of state’s shocking November election defeat—that the Obama team should have done more to publicize the hacking for what it was: a heavy-handed Kremlin intervention on behalf of one side in America’s presidential election. Monaco pushed back against that, recalling that the heads of U.S. intelligence agencies issued a joint statement publicly blaming the Russians for the pre-election hack on Oct. 7. “That was an unprecedented statement,” she says, “a fact that sometimes gets lost in this discussion” given that it came on the same day as the revelation of the “Access Hollywood” tape showing Trump joking about sexually assaulting a woman.

I point to Monaco’s argument because it’s a mirror image to claims Hillary supporters make about the same week. They argue that the release of the John Podesta emails drowned out the Access Hollywood video. Here’s John Podesta in a December appearance on Meet the Press.

So October 7th, Wiki– October 7th, let’s go through the chronology. On October 7th, the Access Hollywood tape comes out. One hour later, WikiLeaks starts dropping my emails into the public. One could say that there might, those things might not have been a coincidence.

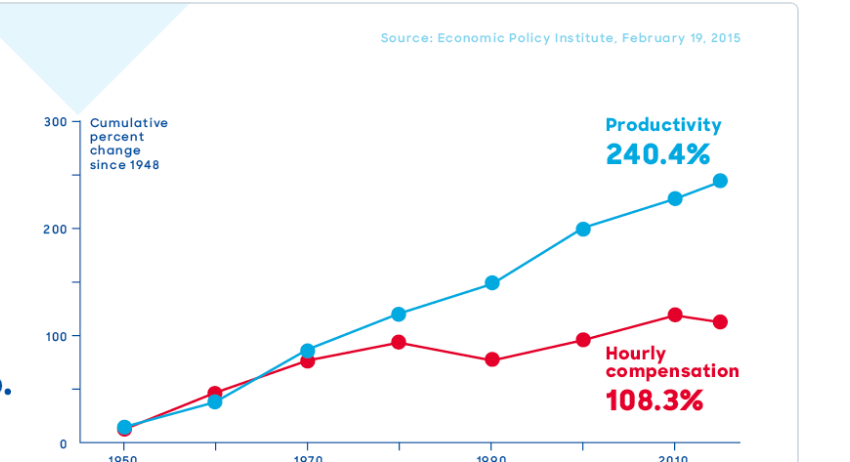

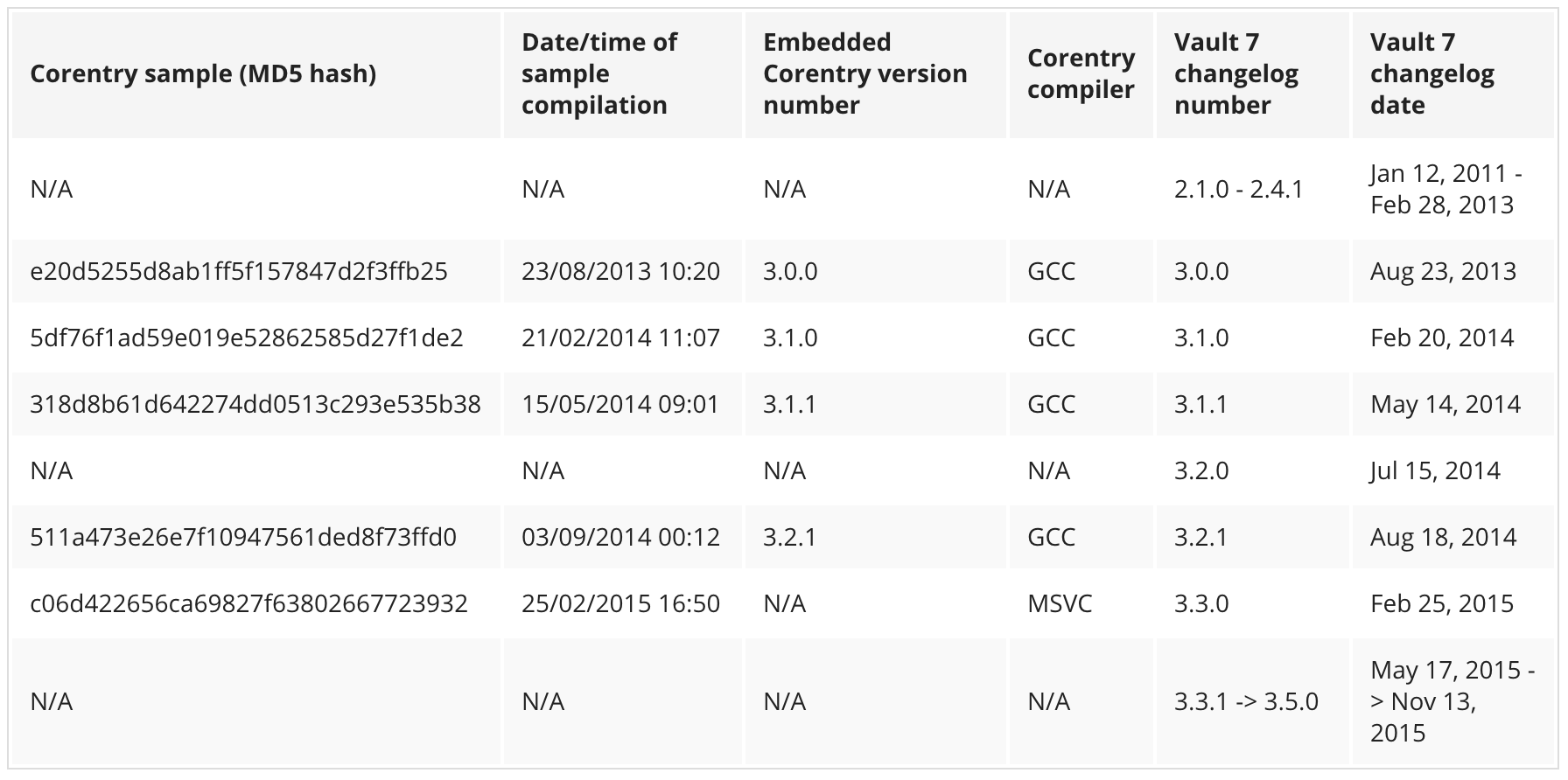

Monaco is in the right here. The Google Trends graph above maps “Wikileaks emails” in blue, “Access Hollywood” in red, and “Russian hack” in yellow (“Grab them by the pussy” shows a more extreme but shorter spike, “John Podesta” doesn’t show as high). In fact, the Grab them by the pussy video drowned out the first releases of the Podesta emails — which suggests it would have been stupid strategy to intentionally release them at the same time, as doing so would mean fewer people would read the excerpts from Hillary’s speeches that got released on the first day. By the following Tuesday, Wikileaks had taken over. By comparison, the Russian hack was a mere blip compared to those two stories, though.

The Roger Stone and Wikileaks narrative misses a few data points

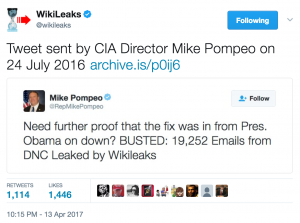

I return to this chronology for another reason. The events of the week of October 3 have been in the news for another reason: their role in the claim that Roger Stone was coordinating with Wikileaks during that week (which is presumably a big part of the reason Podesta insinuated there was coordination on that timing).

CNN has a timeline of many of Stone’s Wikileaks related comments, which actually shows that in August, at least, Stone believed Wikileaks would release Clinton Foundation emails (a claim that derived from other known sources, including Bill Binney’s claim that the NSA should have all the Clinton Foundation emails).

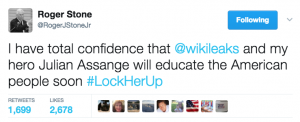

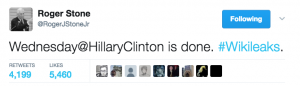

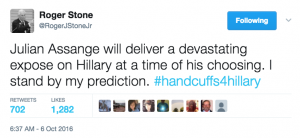

It notes, as many timelines of Stone’s claims do, that on Saturday October 1 (or early morning on October 2 in GMT; the Twitter times in this post have been calculated off the unix time in the source code), Stone said that on Wednesday (October 5), Hillary Clinton is done.

Fewer of these timelines note that Wikileaks didn’t release anything that Wednesday. It did, however, call out Guccifer 2.0’s purported release of Clinton Foundation documents (though the documents were real, they were almost certainly mislabeled Democratic Party documents) on October 5. The fact that Guccifer 2.0 chose to mislabel those documents is worth further consideration, especially given public focus on the Foundation documents rather than other Democratic ones. I’ll come back to that.

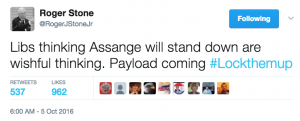

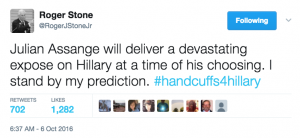

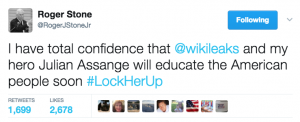

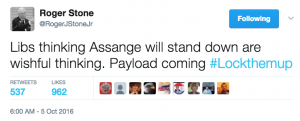

Throughout the week — both before and after the Guccifer 2.0 release — Stone kept tweeting that he trusted the Wikileaks dump was still coming.

Monday, October 3:

Wednesday, October 5 (though this would have been middle of the night ET):

Thursday, October 6 (again, this would have been nighttime ET, after it was clear Wikileaks had not released on Wednesday):

On October 7, at 4:03PM, David Fahrenthold tweeted out the Access Hollywood video.

On October 7, at 4:32 PM, Wikileaks started releasing the Podesta emails.

Stone didn’t really comment on the substance of the Wikileaks release. In fact, even before the Access Hollywood release, he was accusing Bill Clinton of rape, and he continued in that vein after the release of the video, virtually ignoring the Podesta emails.

For its part, Wikileaks was denying it had any knowing contact with Stone within a week, as it had before. CNN finally reported those denials in the wake of reporting on Stone’s August 2016 contacts with Guccifer 2.0. It’s worth noting that in precisely that time period, Wikileaks managed to discredit a still unexplained US-based hoax launched against Julian Assange, accusing him of soliciting a minor via the online dating site Todd and Claire. In addition, this was the period when the odd Alfa Bank story was being pitched to journalists.

Thus far, anyway, the full chronology suggests that either Stone’s information was only vaguely accurate or Wikileaks delayed its release for a few days. That does weird things to Podesta’s narrative, since either Wikileaks delayed their release so the actually newsworthy part of it — Hillary’s speech excerpts — would be overshadowed (as it was) by the Access Hollywood video, or the Access Hollywood video was timed to coincide with the Wikileaks release — which after all had been announced publicly in a way the Access Hollywood video had not been.

Democrats had more warning of impending emails than Podesta makes out

There’s another part of Podesta’s narrative that deserves review. He liked to suggest he had no idea when his emails were being released — in part, to criticize the FBI for not warning him.

It’s not just that Stone appears to have had a vaguer sense of when the next dump (which, as noted, he appeared to believe would be Clinton Foundation emails) was coming than often made out. Democrats also had more warning than often claimed.

In his December Meet the Press appearance, Podesta made a big deal out of the fact that the FBI had not informed him before the October 7 release.

CHUCK TODD:

This is your personal account that was hacked. I’ve got to think you’re getting updates on the investigation that others would not. What can you share?

JOHN PODESTA:

I will share this with you, Chuck. The first time I was contacted by the F.B.I. was two days after WikiLeaks started dropping my emails.

CHUCK TODD:

Let me pause here.

JOHN PODESTA:

The first, the first–

CHUCK TODD:

Two days after?

But as he went on to reveal, he had seen a document released earlier that he had reason to believe may have been from him (I think, but will have to return to this, that it may have been one of the original Guccifer 2.0 documents).

CHUCK TODD:

But when were you aware that you had been hacked? Before October 7th?

JOHN PODESTA:

I think it was confirmed on October 7th in some of the D.N.C. dumps that had occurred earlier.

CHUCK TODD:

Earlier, yeah.

JOHN PODESTA:

And other campaign officials also had their emails divulge earlier than October 7th. But in one of those D.N.C. dumps, there was a document that appeared to me was– that appeared came– might have come from my account. So I wasn’t sure, I didn’t know, I didn’t know what they had, what they didn’t have. It wasn’t until October 7th when Assange both really in his first statements said things that were incorrect, but started dumping them out and said they were going to all dump out. That’s when I knew that they had the contents of my email account.

Even putting aside Podesta’s suspicion one of the release documents had come from him and Stone’s warnings, Podesta would have had one more warning there would be a further release: from the Christopher Steele reports being done as opposition research for the Hillary campaign.

On September 14, Steele reported that the Russians were considering releasing more emails after the September 18 Duma elections, though the Russians thought they might not have to release any more emails to make Hillary look “weak and stupid.”

Russians do have further “kompromat” on CLINTON (e-mails) and considering disseminating it after Duma (legislative elections) in late September. Presidential spokesman PESKOV continues to lead on this.

[snip]

Continuing on this theme, the senior PA official said the situation was that the Kremlin had further “kompromat” on candidate CLINTON and had been considering releasing this via “plausibly deniable” channels after the Duma (legislative elections) were out of the way in mid-September. There was however a growing train of thought and associated lobby, arguing that the Russians could still make candidate CLINTON look “weak and stupid” by provoking her into railing against PUTIN and Russia without the need to release more of her e-mails.

Curiously, as with all other Wikileaks releases, the publicly-released Steele reports never prospectively confirm a release. Steele’s sources seemed to have little prospective insight to offer about non-public events tied to the release of emails. But on October 12, a report (based on undated early October reporting, which raises questions why the reporting on this wasn’t as quick as on some other reports) notes that the Russians have dumped more anti-Clinton material, which would continue until election day.

Russians have injected further anti-CLINTON material into the “plausibly deniable” leaks pipeline which will continue to surface, but best material already in public domain.

[snip]

Speaking separately in confidence to a trusted compatriot in early October 2016, a senior Russian leadership figure and a Foreign Ministry official reported on recent developments concerning the Kremlin’s operation to support Republican candidate Donald TRUMP in the US presidential election. The senior leadership figure said that a degree of buyer’s remorse was setting in among Russian leaders concerning TRUMP, PUTIN and his colleagues were surprised and disappointed that leaks of Democratic candidate, Hillary CLINTON’s hacked e-mails had not had greater impact on the campaign.

Continuing on this theme, the senior leadership figure commented that a stream of further hacked CLINTON material already had been injected by the Kremlin into compliant western media outlets like Wikileaks, which remained at least “plausibly deniable”, so the stream of these would continue through October and up to the election. However s/he understood that the best material the Russians had already was out and there were no real game-changers to come.

Suffice it to say, even without an FBI warning, Podesta had good reason to expect the emails would occur, though he may have had only a vague idea of the timing.

The other missing detail

Which brings me to one final event from that week that rarely makes the timelines, particularly not the Democratic ones (though Glenn Greenwald pointed out some of it in this post).

From at least the time of the DNC email release in July, Democrats insinuated that Russia and/or Wikileaks had doctored the emails, without ever offering proof, besides the original obvious doctoring of metadata in the Guccifer 2.0 documents (though some DNC people have since credibly claimed that not all of their emails got published). Chief among those people was Malcolm Nance, who was writing a book on the hack. He started warning of spoofed emails in late July. He started pitching his book, which predicted the leaks would include tampering, at the end of September.

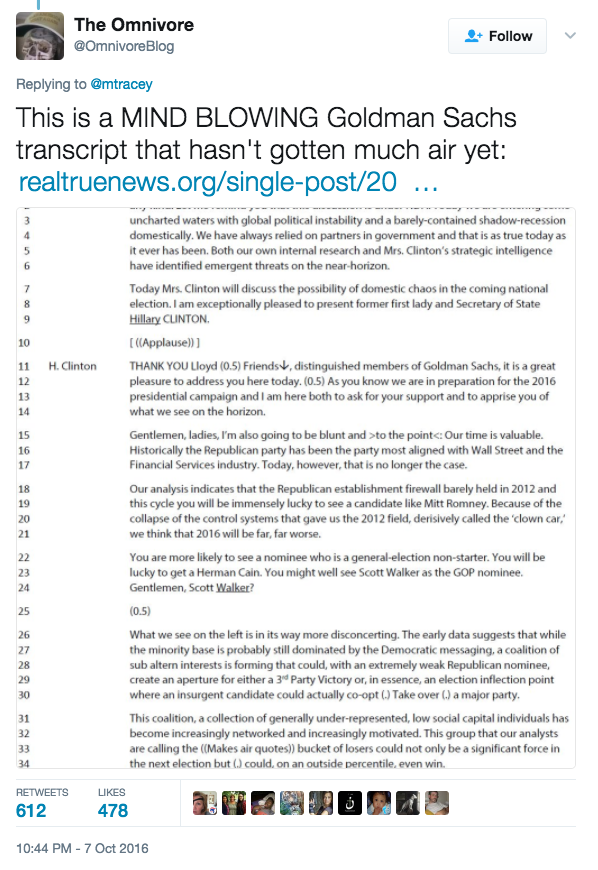

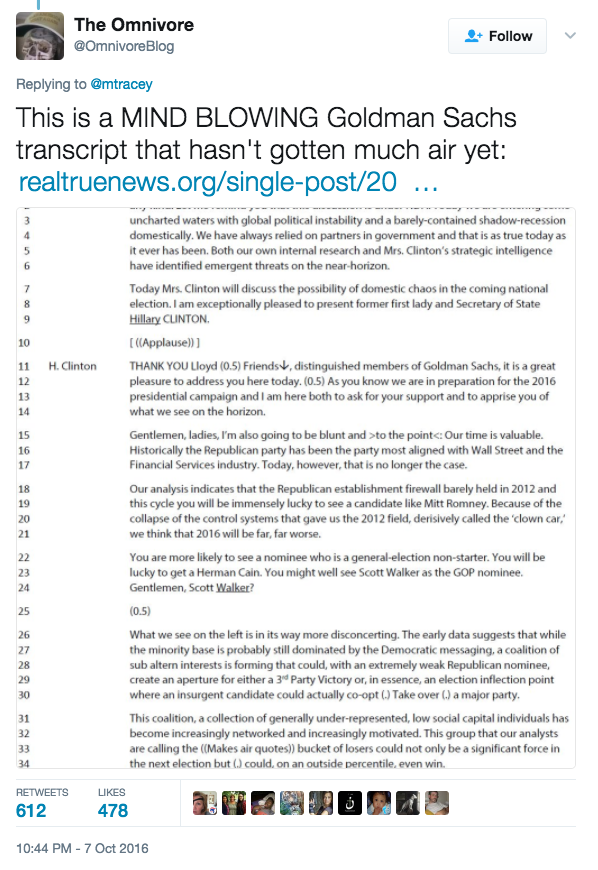

And then, just over an hour after the Podesta emails dropped (5:44PM) documents including excerpts from Hillary’s speeches, a pro-Clinton Twitter account responded to Michael Tracey’s observations about the excerpts with a badly faked transcript of a Hillary Goldman Sachs speech.

At 7:25PM, one of the key Russian story commenters linked to it, accusing “Trumpists” of “dirtying docs.” Then at 7:43PM, Nance tweeted, “Official Warning: #PodestaEmails are already proving to be riddled with obvious forgeries & #blackpropaganda not even professionally done.”

Click through to Greenwald’s post to see how it went viral after that (MSNBC’s Joy Reid, who had repeatedly had Nance on, was key to both of Nance’s claims of forgeries go viral), including how it got picked up in the Democrats’ own fake news sites.

Here’s the thing: in multiple places, the guy who later claimed credit, under the name “Marco Chacon,” for the hoax stated he had done the transcript in advance of the release of the emails.

The biggest breakout I had came when a Vice reporter, Michael Tracey, was holding forth on Twitter in the wake of the Podesta Email leaks. He was speaking about the Goldman Sachs transcripts—and I had one.

I had written up a fake Goldman Sachs transcript days before, wherein Hillary Clinton is preparing a run for president and is speaking to the board of directors in 2014 about the coming threat to Wall Street and Washington power. That threat? Bronies, adult male fans of the cartoon My Little Pony: Friendship Is Magic. She has to explain this “Bronie Threat” to them and, in the process, describes a group of internet denizens she calls a “bucket of losers.”

When I tweeted the link and an image of some of the text at Tracey, I did it because I find him to be something of a self-important git and wanted to poke fun at him. I didn’t know at the time that there were Goldman Sachs transcript fragments in the WikiLeaks release.

Note, too, that his claim that when he tweeted the hoax transcript to Tracey, he didn’t know there were Goldman transcripts in the Wikileaks release is laughable: That’s what Tracey’s tweet was about!

Just days later, Kurt Eichenwald would make another claim that Russia had doctored emails that went even more wildly viral (and became among the most remembered fake news stories of the election cycle). In Eichenwald’s discussions with the Sputnik writer in question, Bill Moran, he insisted that spooks had alerted him to the (mis)use of his story.

There is definitely evidence that Roger Stone had at least enough feedback with those leaking stolen emails to know to expect them the first week of October — though he clearly didn’t know precisely when or what to expect. Moreover, he clearly didn’t have an open channel with Assange to find out when the delayed release would be — it appears, instead, he got a warning, but no update.

But there are at least as many reasons to ask whether the Democrats (or perhaps even a government agency) had advance warning of what was coming, and had planned in response.

And all that played out at the time when, per Lisa Monaco, the Intelligence Community made what they viewed as an unprecedented announcement blaming Russia for the hack of the Democrats.

There are definitely reasons to scrutinize Stone’s foreknowledge in all this. But that is by no means the only feedback loop that appears to have been in operation by this point.