I’ve covered a great deal of prosecutions involving FISA materials. In just one — that of Reaz Qadir Khan — was the defendant able to use sensitivities around FISA to get a better plea deal (and in that case, there were extenuating circumstances, possibly including a dead FISA target and Stellar Wind collection). I also covered the Scooter Libby case, in which Libby attempted — and very nearly succeeded — in forcing prosecutors to dismiss the case by demanding the declassification of a slew of Presidential Daily Briefs. But even the Libby case may pale in comparison to the difficulties John Durham has signed up for in his prosecution of Igor Danchenko.

That’s true because Danchenko will credibly be able to demand materials from at least two FISA orders, as well as two other counterintelligence investigations, including a sensitive, multi-pronged, ongoing investigation, to defend himself.

Indeed, there’s even a chance DOJ cannot legally prosecute Danchenko in this case.

What follows is true regardless of whether Danchenko was indicted on shoddy evidence as part of a witch hunt or if Durham has Danchenko dead to rights defrauding the FBI to target Donald Trump. I remain agnostic which is the case (the truth is likely somewhere in-between). It is true regardless of whether Carter Page and Sergei Millian were truly victimized as a result of the Steele dossier, or whether they were reasonable counterintelligence targets whose investigations got blown up in a political firestorm.

This has everything to do with the prosecutorial discretion that Durham did not exercise in charging Danchenko (and because of some sloppiness in the way he did so) and nothing to do with Danchenko’s guilt or innocence or Page and Millian’s victimization.

Consider the following moves Durham made in his indictment:

- He invoked Danchenko’s source, Olga Galkina, in his materiality claims and based his single charge pertaining to Charles Dolan on a June 15, 2017 FBI interview.

- He relied on claims Sergei Millian made about interactions with Danchenko as part of his proof that Danchenko lied about his belief that he had spoken with Millian. Durham did so, apparently, based entirely on Millian’s currently public Twitter blatherings.

- He made Carter Page’s FISA targeting — and its role in the investigation into Trump associates (which Durham recklessly called “the Trump campaign”) — central to his materiality claims.

Whether Igor Danchenko is a reckless smear agent or someone screwed by Christopher Steele’s own sloppiness, he is entitled to all the evidence pertaining to the full scope of the indictment, as well as any exculpatory evidence that could help him disprove Durham’s claims. One of the prosecutors in the case, Michael Keilty, already warned Judge Anthony Trenga, who is presiding over the case, that there will be “a vast amount of classified discovery” in this case. But if prosecutors haven’t vetted Millian any further than reading his Twitter feed, they may have no idea what discovery challenges they face.

There has never been a case like this one, relying on two already publicly identified FISA orders, so this is literally uncharted waters.

Durham’s Matryoshka Materiality Claims

Before I explain the challenges Durham faces, it’s worth explaining how Durham has used materiality in this indictment. Durham will have to prove not just that Danchenko lied, but that the lies were material.

The words “material” or “materiality” show up in the indictment 20 times, of which just one instance is used to mean “stuff” (in a misquotation of a Danchenko response to an FBI question stating, “related issues perhaps but … nothing specific”). Five are required in the charging language.

Maybe Durham focused so much making claims about materiality, in part, because he’s smarting about the way people made fun of him for his shoddy materiality claims in the Michael Sussmann indictment. But many of his discussions about the “materiality” of Danchenko’s alleged lies, both charged and uncharged, serve as a gratuitous way for Durham to include accusations in the indictment he didn’t charge. The tactic worked like a charm, as multiple journalists reported that things — particularly regarding the pee tape — were alleged or charged that were not. But now he’s on the hook for them in discovery.

Below, I’ve shown how these materiality claims form a nested set of allegations, such that even the materiality claims for uncharged conduct make up part of his overall materiality argument. I’m not, at all, contesting that Durham has a sound case that — if he can prove Danchenko lied — at least one of lies was material. While some of his materiality claims are provably false and some (such as the claims that Danchenko’s alleged lies about Millian in October and November 2017 mattered for FISA coverage that ended in September 2017) defy physics, the bar for materiality is low and he will clearly surpass it on some of his materiality claims.

The issue, however, is that Durham is now on the hook, with regards to discovery, for all of his materiality claims covering both the charged lies and the uncharged allegations. Danchenko may now demand evidence that undercuts these claims, even the ones that don’t relate directly to the charged lies.

The Section 702 directive targeting Olga Galkina

Durham makes two materiality claims pertaining to Danchenko’s friend, Olga Galkina, to whom he sourced all the discredited Michael Cohen reports and a claim about Carter Page’s meetings in July 2016:

- That by lying about how indiscreet he was about his relationship with Christopher Steele, Danchenko prevented the FBI from learning that Russian spies might inject disinformation into the dossier through people like Galkina.

- That by lying on June 15, 2017, Danchenko prevented the FBI from learning that Charles Dolan “maintained a pre-existing and ongoing relationship” with Galkina, which led Galkina to have access to senior Russian officials she wouldn’t otherwise have had. Dolan’s ties with Galkina also appear to have led to Galkina serving as a cut-out between Dolan and Danchenko for information for one of the reports (pertaining to the reassignment of a US Embassy staffer) in the dossier.

I’m unclear why Durham made these claims — possibly because it was one of the only ways to criminalize the way Dolan served as a source for reports that were unrelated to the Carter Page applications, possibly because he wanted to do so to dump HILLARY HILLARY HILLARY in the middle of his indictment. But both claims are false.

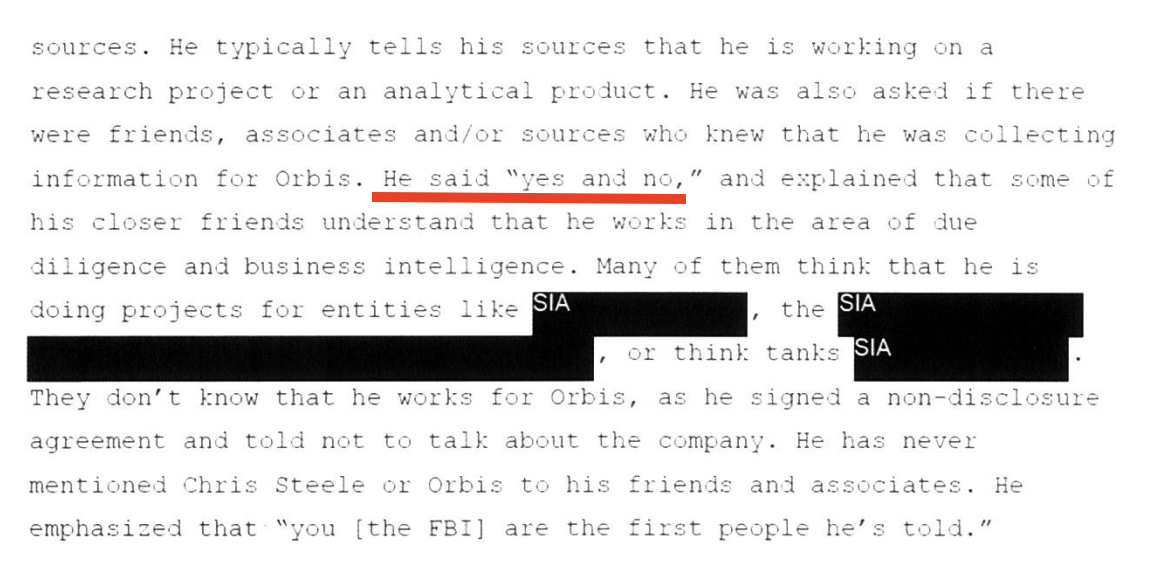

To prove the first is false, Danchenko will point to Durham’s miscitation of the question Danchenko was actually asked, his answer — “yes and no” — to a question Durham claims he answered “no” to, and to his descriptions, from his very first interview, of how Galkina knew he was collecting intelligence and had even, after the release of the dossier, tasked him with an intelligence collection request herself.

To prove the second is false, Danchenko will point to the declassified footnote in the DOJ IG Report showing that in “early June 2017” (and so, presumably before June 15), the FBI obtained 702 collection that (the indictment makes clear) reflects extensive communications between Dolan and Galkina.

The FBI [received information in early June 2017 which revealed that, among other things, there were [redacted]] personal and business ties between the sub-source and Steele’s Primary Sub-source; contacts between the sub-source and an individual in the Russian Presidential Administration in June/July 2016; [redacted] and the sub‐source voicing strong support for candidate Clinton in the 2016 U.S. elections. The Supervisory Intel Analyst told us that the FBI did not have Section 702 coverage on any other Steele sub‐source. [my emphasis]

It’s highly likely the FBI set up that June 15, 2017 interview with Danchenko precisely to ask him about things they learned via that Section 702 collection. Based on what Durham has said so far, Danchenko provided information about key details of the relationship between Galkina and Dolan in the interview, thereby validating that he was not hiding the relationship entirely.

Had Danchenko affirmatively lied about this in January or March 2017, rather than just not sharing this information, Durham might have a case. But by June 2017, the FBI was already sitting on that 702 collection (to say nothing of the contact tracing analysts would have used to justify the 702 directive). That’s almost certainly why they asked the question about Dolan.

So even if Durham could manage to avoid introducing, as evidence at trial, Danchenko’s communications with Galkina that the FBI would have first obtained under FISA 702, and thereby stave off the FISA notice process required for aggrieved persons under FISA, Danchenko is still going to have cause to make Durham admit a slew of things about that Section 702 directive targeting Galkina, including:

- What kind of contact-tracing alerted the FBI and NSA that Galkina had US-cloud based communications that would be of investigative interest (because that contact-tracing, by itself, disproves Durham’s materiality claim)

- What communications FBI obtained from that Section 702 order and when (because if they indeed had the Galkina-Dolan communications on June 15, then nothing Danchenko could have said impeded the FBI from discovering them)

- The approval process behind the release of this Section 702 information to Inspector General Michael Horowitz, and then to Congress, which in turn presumably alerted Durham to it, and whether it complied with new requirements about unmasking imposed in 2018 in response to the Carter Page FISA and conspiracy theories about Mike Flynn (it surely did, because unmasking for FBI collections is not really a thing, but Danchenko will have reason to ask how Congress got the communications and from there, how Durham did)

None of this kind of information has been released to a defendant before, but all of it is squarely material to combatting the claim that the FBI didn’t know about Galkina’s communications with Dolan when they asked Danchenko a question precisely because they did know about those communications. And Danchenko has the right to ask for it because of that reference to Section 702 that Ron Johnson and Chuck Grassley insisted on declassifying.

The Sergei Millian counterintelligence investigation

The paragraph describing that Durham is relying on Sergei Millian’s Twitter rants as part of his evidence to prove that Danchenko lied five times about Millian (just four of which are charged) misspells Danchenko’s name, the single such misspelling in the indictment. [Update: Though see William Ockham’s comment below that notes there’s a different misspelling of Danchenko’s name elsewhere in the Millian part of the indictment.]

Chamber President-1 has claimed in public statements and on social media that he never responded to DANCHEKNO’s [sic] emails, and that he and DANCHENKO never met or communicated.

That makes me wonder whether it was added in at the last minute, after all the proof-reading, perhaps in response to a question from the grand jury or Durham’s supervisors. If it was, it might indicate that Durham didn’t really think through all the implications of invoking Millian as a fact witness against Danchenko.

But, unless Durham has rock-solid proof that Danchenko invented a call he claimed to believe had involved Millian altogether, then this reference now gives Danchenko cause to submit incredibly broad discovery requests about Millian to discredit Millian as a witness against him. Durham made no claim that he has such rock-solid proof in the indictment. As I’ve noted, Danchenko told the FBI he replaced his phone by the time the Bureau started vetting the Steele dossier, so to rule out that the call occurred, Durham probably would need to have obtained the phone and found sufficient evidence that survived a factory reset to rule out a Signal call.

Before I explain all the things Danchenko will have good reason to demand, let me review Durham’s explanation for why the alleged lies about Millian (Durham has charged separate lies on March 16, May 18, October 24, and November 16, 2017) were material:

Based on the foregoing, DANCHENKO’s lies to the FBI claiming to have received a late July 2016 anonymous phone call from an individual that DANCHENKO believed to be Chamber President-1 were highly material to the FBI because, among other reasons, the allegations sourced to Chamber President-1 by DANCHENKO formed the basis of a Company Report that, in turn, underpinned the aforementioned four FISA applications targeting a U.S. citizen (Advisor 1). Indeed, the allegations sourced to Chamber President-1 played a key role in the FBI’s investigative decisions and in sworn representations that the FBI made to the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court throughout the relevant time period. Further, at all times relevant to this Indictment, the FBI continued its attempts to analyze, vet, and corroborate the information in the Company Reports. [my emphasis]

As I have noted above, it is temporally nonsensical to claim that lies Danchenko told in October and November 2017 “played a role in sworn representations that the FBI made to FISC” when the last such representation was made in June 2017. And Danchenko will be able to make a solid case that no matter what he said in March and May, it would have had no impact on the targeting of Carter Page, because as a 400-page report lays out in depth, really damning details about the Millian claim that Danchenko freely did share in January had no impact on the targeting of Carter Page. Even derogatory things Christopher Steele said about Millian in October 2016 never made any of the Page FISA applications. The DOJ IG has claimed and Judge Rosemary Collyer agreed that FBI was at fault for all this, because they weren’t integrating any of the new information learned from vetting the dossier. Danchenko might even be able to call a bunch of FBI witnesses who were fired as a result to prove they were held accountable for it and so he can’t be blamed.

So Durham will substantially have to rely on “investigative decisions” and FBI efforts to vet the dossier to prove that Danchenko’s claimed lies about Millian were material. And that will make the FBI investigations into Millian himself and George Papadopoulos relevant and helpful to Danchenko’s defense, because those are some of the investigative decisions at issue.

That’s not the only reason that Danchenko will be able to demand that DOJ share information on Millian. Durham has made Millian a fact witness against Danchenko, and — by relying on Millian’s Twitter feed — in the most ridiculous possible way. So Danchenko will be able to demand evidence that DOJ should possesses (but may not) that he can use to explain why Millian might lie about a call between the two.

Some things Danchenko will credibly be able to demand in discovery include:

- Extensive details about Sergei Millian’s Twitter account. Durham presented Millian’s Twitter account to the grand jury as authoritative with regards to Millian’s denials of having any direct call with Danchenko. Danchenko has reason to ask Durham for an explanation why he did so, as well as a collection of all tweets that Millian has made going back to 2016 (most of which Millian has since deleted, some of which will raise questions about Millian’s sincerity and claimed knowledge of non-public information). In addition, because there have been questions (probably baseless, but nevertheless persistent) during this period about whether Millian was personally running his own Twitter campaign, Danchenko can present good cause to ask for the IP and log-in information for the entire period, either from the government or from Twitter. While it would be more of a stretch, Millian’s Twitter crowd includes some accounts that have been identified as inauthentic by Twitter and others that were involved in publicly exposing Danchenko’s identity; Danchenko might point to this as further evidence of Millian’s motives behind his Twitter rants. Finally, Danchenko will also have cause to ask how Millian got seeming advance notice of his own indictment if Durham’s investigators never bothered to put Millian before a grand jury.

- Details of the counterintelligence investigation into Millian. After the first release of the DOJ IG Report, the FBI declassified parts of discussions of a counterintelligence investigation that the New York Field Office opened into Millian days before October 12, 2016. The IG Report describes that Millian was “previously known to the FBI,” and does not tie that CI investigation to any allegations that Fusion made against Millian (though I don’t rule it out). Danchenko will obviously be able to ask for access to the still-redacted parts of those IG Report references, because the same things (whatever they were) that led FBI to think Millian was a spy would be things that Danchenko could use to offer a motive for why Millian would lie about having spoken to Danchenko. Danchenko also has cause to ask for details from Millian’s own FBI file. The basis for that counterintelligence investigation, and any derogatory conclusions, would provide Danchenko means to raise questions about Millian’s credibility or at least alternative motives for Millian to claim no such call took place.

- Details of how Millian cultivated George Papadopoulos. The IG Report also reveals that, even before the Carter Page application, the FBI was aware of the extensive ties between Millian and George Papadopoulos. Because Durham claims that Danchenko’s alleged lies — and not direct evidence pertaining to the relationship between Millian and Papadopoulos — drove the FBI’s investigative decisions from 2017 through the end of the Mueller investigation, Danchenko will have reason to ask for non-public details about some aspects of the Papadopoulos investigation, as well, not least because (as the Mueller Report makes clear) the initial contacts between Millian and Papadopoulos exactly parallel in time — and adopted the same proposed initial meeting approach — the initial contact and the call that Danchenko claimed to believe he had with Millian. If the July 2016 call he believes he had with Millian didn’t occur, Danchenko will be able to argue persuasively, then how did he know precisely where and how Millian would conduct such meetings a week in advance of the initial meeting, in New York, that Millian had with Papadopoulos?

The Office investigated another Russia-related contact with Papadopoulos. The Office was not fully able to explore the contact because the individual at issue-Sergei Millian-remained out of the country since the inception of our investigation and declined to meet with members of the Office despite our repeated efforts to obtain an interview. Papadopoulos first connected with Millian via Linked-In on July 15, 2016, shortly after Papadopoulos had attended the TAG Summit with Clovis.500 Millian, an American citizen who is a native of Belarus, introduced himself “as president of [the] New York-based Russian American Chamber of Commerce,” and claimed that through that position he had ” insider knowledge and direct access to the top hierarchy in Russian politics.”501 Papadopoulos asked Timofeev whether he had heard of Millian.502 Although Timofeev said no,503 Papadopoulos met Millian in New York City.504 The meetings took place on July 30 and August 1, 2016.505 Afterwards, Millian invited Papadopoulos to attend-and potentially speak at-two international energy conferences, including one that was to be held in Moscow in September 2016.506 Papadopoulos ultimately did not attend either conference.

On July 31 , 2016, following his first in-person meeting with Millian, Papadopoulos emailed Trump Campaign official Bo Denysyk to say that he had been contacted “by some leaders of Russian-American voters here in the US about their interest in voting for Mr. Trump,” and to ask whether he should “put you in touch with their group (US-Russia chamber of commerce).”507 Denysyk thanked Papadopoulos “for taking the initiative,” but asked him to “hold off with outreach to Russian-Americans” because “too many articles” had already portrayed the Campaign, then-campaign chairman Paul Manafort, and candidate Trump as “being pro-Russian.”508

On August 23, 2016, Millian sent a Facebook message to Papadopoulos promising that he would ” share with you a disruptive technology that might be instrumental in your political work for the campaign.”509 Papadopoulos claimed to have no recollection of this matter.510

On November 9, 2016, shortly after the election, Papadopoulos arranged to meet Millian in Chicago to discuss business opportunities, including potential work with Russian “billionaires who are not under sanctions.”511 The meeting took place on November 14, 2016, at the Trump Hotel and Tower in Chicago.512 According to Papadopoulos, the two men discussed partnering on business deals, but Papadopoulos perceived that Millian’s attitude toward him changed when Papadopoulos stated that he was only pursuing private-sector opportunities and was not interested in a job in the Administration.5 13 The two remained in contact, however, and had extended online discussions about possible business opportunities in Russia. 514 The two also arranged to meet at a Washington, D.C. bar when both attended Trump’s inauguration in late January 2017.515 [my emphasis]

John Durham claims that Sergei Millian is a victim. But by making Millian a fact witness against Danchenko, Durham has given Danchenko the opportunity to obtain and air a great many details about why a DOJ prosecutor should review more than Twitter rants before treating Millian as a credible fact witness.

The Oleg Deripaska counterintelligence and sanctions investigations

Durham has also provided Danchenko multiple reasons to request details of a counterintelligence investigation that is ongoing and remains far more sensitive than the Millian one: The investigation into Oleg Deripaska.

Oleg Deripaska was the most likely client for a tasking Steele gave Danchenko immediately before the DNC one, collecting on Paul Manafort. Danchenko credibly claimed to the FBI that he did not know what client had hired Steele. If Deripaska was that client, it would be relevant and helpful to Danchenko’s defense to understand why Deripaska hired Steele.

That’s true, in significant part, because Deripaska is also the most likely culprit behind any disinformation injected into the Steele dossier. Among other things, by asking Steele to collect on Manafort and then monitoring how Steele did that, Deripaska could have used it to identify Steele’s reporting network.

Durham blames Danchenko for hiding the possibility of disinformation with one of his (false) uncharged conduct claims, but the Deripaska angle, about which Danchenko claimed to have no visibility either in real time in 2016 or by 2017, when he is accused of lying, would be the more important angle. And we know they were aware of the possibility and trying to assess whether that was possible even as they were vetting the dossier. But, as Bill Priestap told DOJ IG, he couldn’t figure out how this would work.

what he has tried to explain to anybody who will listen is if that’s the theory [that Russian Oligarch 1 ran a disinformation campaign through [Steele] to the FBI], then I’m struggling with what the goal was. So, because, obviously, what [Steele] reported was not helpful, you could argue, to then [candidate] Trump. And if you guys recall, nobody thought then candidate Trump was going to win the election. Why the Russians, and [Russian Oligarch 1] is supposed to be close, very close to the Kremlin, why the Russians would try to denigrate an opponent that the intel community later said they were in favor of who didn’t really have a chance at winning, I’m struggling, with, when you know the Russians, and this I know from my Intelligence Community work: they favored Trump, they’re trying to denigrate Clinton, and they wanted to sow chaos. I don’t know why you’d run a disinformation campaign to denigrate Trump on the side. [brackets original]

Since Durham blamed Danchenko for hiding the possibility of disinformation when questions like these did more to impede such considerations, Danchenko has good reason to ask for anything assessing whether Deripaska did use the dossier as disinformation, not least because DOJ was getting ample information to pursue that angle before Danchenko’s first interview, via Bruce Ohr (for which DOJ fired Ohr).

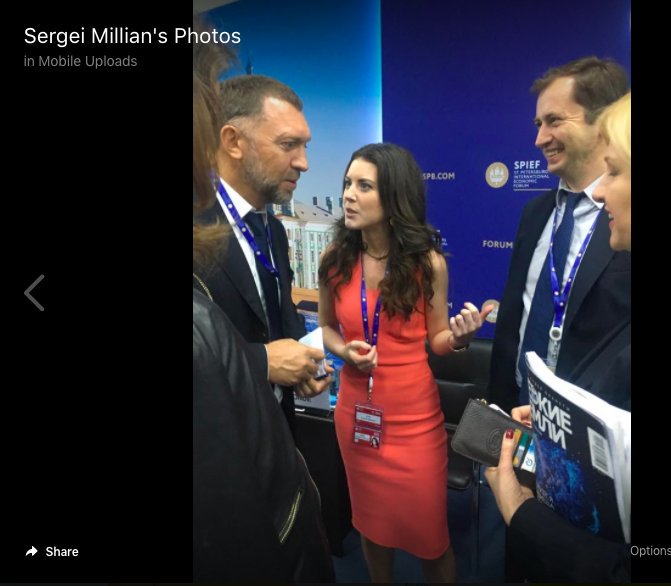

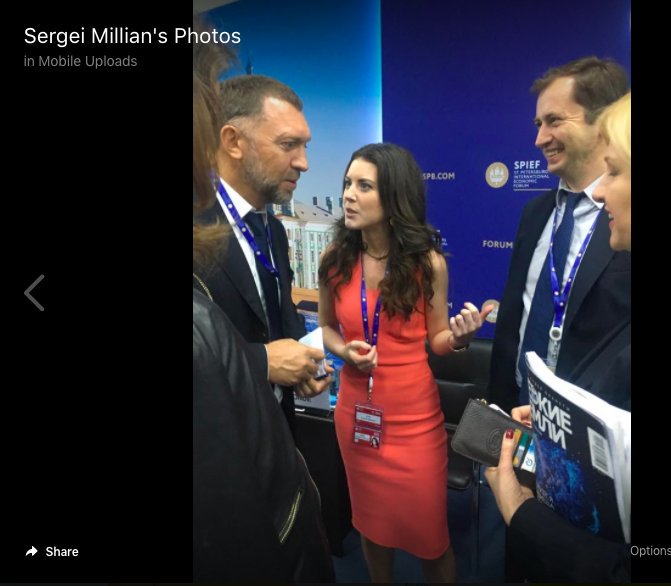

There’s a Millian angle to Danchenko’s case he should get information on the counterintelligence investigation into Deripaska, too. At a time when Deripaska was already tasking both sides of his double game — using Christopher Steele to make Paul Manafort legally vulnerable and then using Manafort’s legal and financial vulnerability to entice his cooperation in the election operation — Deripaska and Millian met at the St. Petersburg International Economic Forum in June 2016, the same convention that Michael Cohen was invited to attend to pursue an impossibly lucrative Trump Tower deal and to which Russian Deputy Prime Minister Sergei Prikhodko repeatedly invited Trump (as this post makes clear, Mueller obtained only unsigned versions of Trump’s letter declining Prikhodko’s invitation).

Millian’s documented meeting with Deripaska during 2016 would provide Danchenko several reasons to want access to some of the investigative materials from the Deripaska investigations. First, if Millian and Deripaska had further contact, either in 2016, or since then, it would suggest that Millian’s denials that he called Danchenko may be part of the same disinformation strategy as any disinformation inserted via Deripaska-linked sources into the dossier itself.

If Millian had no ongoing relationship with Deripaska after they met up in June 2016, however, it suggests a possible alternate explanation for the call that, Danchenko consistently claimed in 2017, he believed to be Millian: That someone learned of Danchenko’s outreach (the Novosti journalists through whom Danchenko first got Millian’s contact information are one possible source of this information, but not the only one) and called Danchenko seemingly in response to Danchenko’s outreach to Millian as another way to inject disinformation into the dossier.

Finally, Danchenko may request information on Deripaska to unpack the provenance of the investigation against him altogether. After meeting with a Deripaska deputy in January 2017, Paul Manafort returned to the US and pushed a strategy to discredit the Russian investigation by discrediting the dossier, using Deripaska’s associate Konstantin Kilimnik to obtain information about its sources. That strategy adopted by Manafort is a strategy that has led, directly, to this Durham inquiry.

If Deripaska participated in any disinformation efforts involving the dossier and instructed Manafort to exploit the disinformation he knew had been planted — if this very investigation is the fruit of the same disinformation campaign that Durham blames Danchenko for hiding — then Danchenko would have good reason to make broad discovery requests about it.

DOJ has continued to redact Deripaska-related investigative detail under ongoing investigation exemptions. And Treasury refused Deripaska’s own attempt to learn why he was sanctioned. So it’s likely DOJ would want to guard these details closely.

But Deripaska’s key role in the Russian operation even as he was tasking Steele to harm Manafort, the tie between Millian and Deripaska, and the effort to use the dossier to discredit the Russian investigation make such requests directly relevant and helpful to Danchenko’s defense.

The Carter Page FISA Collection

This entire Durham investigation is, at least metonymically, an attempt to avenge Carter Page’s (and through him, Trump’s) purported victimization at the hands of the Steele dossier.

But even with Page, Durham’s materiality claims may expose Page to more scrutiny than he ever would have been without this case. Page may well have been victimized by the dossier itself, but Danchenko is not accused of any crime in conjunction with his collection related to the dossier. Instead, he is charged with lies to the FBI in March, May, October, and November 2017. There’s plenty of evidence in the 400-page DOJ IG Report that nothing Danchenko could have said in those earlier interviews could have altered FISA targeting decisions in April and June, and it would be impossible for lies told in October and November to have affected coverage that ended in September.

That means that Durham will have to provide Danchenko a great deal of information on the investigation into Page — including on Page’s willing sharing of non-public information with Russians in 2013, his seeming efforts to reestablish contact with the Russians in 2015, his enthusiastic pursuit of Russian funding to set up a think tank in 2016, and his ongoing connections in 2017 — to afford Danchenko the ability to argue that the dossier didn’t matter because, as a Republican Congressperson with access to all the intelligence told me in July 2018, the case for surveilling Page was a slam dunk even without it.

Providing Danchenko the Mueller materials will be the easy part. They would be helpful to Danchenko’s defense because they show that rumors about Page meeting Igor Sechin were circulating Moscow, not just among Steele’s sources; there was time during Page’s July 2016 trip to Moscow that was unaccounted for, even to those who organized his trip; and via the Page investigation, Mueller corroborated that Kirill Dimitriev (the guy who had a back channel meeting with Erik Prince) would be an important source on Russia’s tracking of Trump. Mueller materials will also show that the FBI came to suspect that one of the contacts involved in bringing Page to Russia in July 2016 was being recruited by Russian spies, providing independent reason to continue the investigation into Page. Mueller investigative materials will provide new details on Konstantin Kilimnik’s report to Paul Manafort that Page was claiming to speak on Trump’s behalf on his trip to Moscow in December 2016, something that may have exposed Trump as a victim of Page’s misrepresentations in Russia, which in turn, heightened the import of learning why Page was making such claims. Language from Mueller’s still-classified description of his decision not to charge Page as a Russian agent may also prove relevant and helpful to Danchenko’s defense.

But it’s not just the Mueller materials. To combat Durham’s claim that Danchenko’s claimed lies were material to the ongoing targeting of Carter Page in April and June 2017, the defendant obviously must be given access to substantial materials from Page’s FISA applications (October 2016, January 2017, April 2017, June 2017). Danchenko will be able to undercut Durham’s materiality arguments in at least two ways with these materials. First, as Andrew McCabe understood it, the first period of FISA collection was “very productive,” and others at FBI described that the collection showed Page’s, “access to individuals in Russia and [his communications] with people in the Trump campaign, which created a concern that Russia could use their influence with Carter Page to effect policy.” Danchenko can certainly ask for these discussions to argue that, even before he ever spoke to the FBI in January 2017, things the FBI learned by targeting Page under FISA created new reason to continue to task him, independent of the dossier.

Even more critically, redacted passages of the DOJ IG Report suggest that the decision to continue targeting Page in June 2017 stemmed almost entirely from a desire to get to financial and encrypted app information from Page that might not be otherwise available.

[A]vailable documents indicate that one of the focuses of the Carter Page investigation at this time was obtaining his financial records. NYFO sought compulsory legal process in April 2017 for banking and financial records for Carter Page and his company, Global Energy Capital, as well as information relating to two encrypted online applications, one of which Page utilized on his cell phone. Documents reflect that agents also conducted multiple interviews of individuals associated with Carter Page.

Case Agent 6 told us, and documents reflect, that despite the ongoing investigation, the team did not expect to renew the Carter Page FISA before Renewal Application No. 2’s authority expired on June 30. Case Agent 6 said that the FISA collection the FBI had received during the second renewal period was not yielding any new information. The OGC Attorney told us that when the FBI was considering whether to seek further FISA authority following Renewal Application No. 2, the FISA was “starting to go dark.” During one of the March 2017 interviews, Page told Case Agent 1 and Case Agent 6 that he believed he was under surveillance and the agents did not believe continued surveillance would provide any relevant information. Cast Agent 6 said [redacted]

SSA 5 and SSA 2 said that further investigation yielded previously unknown locations that they believed could provide information of investigative value, and they decided to seek another renewal. Specifically, SSA 5 and Case Agent 6 told us, and documents reflect, that [redacted] they decided to seek a third renewal. [redacted]

If declassified versions of this report (and the underlying back-up) confirm that, it means Danchenko’s alleged lies in May and June were virtually meaningless in ongoing decisions to target Page, because FBI would otherwise have detasked him if not for very specific accounts they wanted to target. Danchenko would need to be able to get declassified versions of that material to be able to make that argument.

Then there’s the FISA collection used to reauthorize FISA targeting on Page. There’s enough public about what FBI obtained for Danchenko to argue that he needs this collection to rebut the materiality claims Durham has made. For example, one redacted passage in reauthorization applications suggests that FBI learned information about whether Page’s break with the campaign was as significant as the campaign publicly claimed it was. Another redacted passage suggests FBI may have obtained intelligence that contradicted Page’s denials of certain meetings in Russia. A third redacted passage suggests that the FBI learned that Page was engaged in a limited hangout with his admissions of such meetings. Not only might some of this validate the dossier (and explain why Mueller treated the question of Page’s trips to Russia as inconclusive), but it provides specific reasons the FISA collection justified suspicions of Page, meaning FBI was no longer relying on the dossier.

Finally, since Durham claims that Danchenko’s lies impeded the FBI’s efforts to vet the dossier, Danchenko will need to be provided a great deal of information on those efforts. This is another instance where files released as part of Trump’s efforts to undermine the investigation will help Danchenko prove there are discoverable materials he should get. This spreadsheet is what FBI used to vet the dossier. It shows that the FBI obtained information under the Carter Page FISA they used to vet a claim Danchenko sourced to his friend, Galkina, whom Durham made central to questions of materiality. Similarly, the FBI used information from the Page FISA to help vet the claim that Danchenko sourced (incorrectly or not) to Millian, which is utterly central to the case against him. Given Durham’s claims that Danchenko’s lies prevented FBI from doing this vetting, he can easily claim that obtaining this vetting information may be helpful and material to his defense (though it may in fact not be helpful).

This is a very long list and I’m not saying that Danchenko will succeed in getting this information, much less using it at trial.

What I’m saying is that it is quite literally unprecedented for a defendant to know specific details of two FISA orders — the 702 directive targeting Galkina and the Carter Page FISAs — that they can make credible arguments they need access to to mount a defense. Similarly, the ongoing, sensitive counterintelligence investigation into Oleg Deripaska (and Konstantin Kilimnik) is central to the background of the dossier. And Durham has made someone who — like Danchenko before him, was investigated as a potential Russian asset — a fact witness in this case.

Normally, prosecutors might look at the discovery challenges such legitimate defense demands would pose and decide not to try the case (it’s one likely reason, for example, why David Petraeus got away with a wrist-slap for sharing code-word information with his mistress, because the discovery to actually prosecute him would have done more damage than the conviction was worth; similarly, the secrecy of some evidence Mueller accessed likely drove some of his declination decisions). But Durham didn’t do so. He has committed himself to deal with some of the most sensitive discovery ever provided, and to do so with a foreign national defendant, all in pursuit of five not very well-argued false statements charges. That doesn’t mean Danchenko will get the evidence. But it means Durham is now stuck dealing with unprecedented discovery challenges.

In a follow-up, I’ll talk about how this will work and why it may be literally impossible for Durham to succeed.

Update: I’ve corrected the date of the month of the charged interview pertaining to Charles Dolan.

Update: In a story on an ongoing counterintellience investigation into a Russian expat group, Scott Stedman notes that the group was involved in Millian’s pitch to Papadopoulos in 2016.

Forensic News can reveal that Gladysh’s pro-Trump internet activity was much broader than previously known. In 2020, Gladysh’s Seattle-based Russian-American Cooperation Initiative founded a news website that nearly exclusively promoted Trump and disseminated Russian propaganda, according to internet archives.

The news website featured articles with the titles such as “Second Trump term is crucial to prospect of better U.S.-Russia relations, safer world,” and “Biden victory will spell disaster for U.S.-Russia relations, warns billionaire.” The billionaire referenced by the outlet is Oleg Deripaska, a key figure in the 2016 Trump campaign’s collusion with Russia.

[snip]

Morgulis attempted to rally Russian voters for Donald Trump in both the 2016 and 2020 U.S. Presidential Elections and allied himself with numerous associates connected to Russian intelligence and influence operations that have caught the attention of the FBI.

According to the Washington Post, Morgulis and Sergei Millian worked on a plan to rally Russian voters for Trump in 2016. Millian, who was in contact with Trump aide George Papadopoulos, later fled the country and was not able to be interviewed by investigators.

[snip]

Morgulis, Branson, and Millian all received Silver Archer Awards in 2015, a Russian public affairs accomplishment given to U.S. persons advancing Russian cultural and business interests. The founder of Silver Archer is Igor Pisarsky, a “Kremlin-linked public relations power player” who facilitated money transfers from a Russian oligarch to Maria Butina.

This will provide Danchenko cause to ask for details of that counterintelligence investigation.

Durham’s Materiality Claims

Durham’s general materiality argument makes three claims about the way that Danchenko’s alleged lies affected the FBI investigation. And then, nested underneath those claims, he made further claims (about half of which aren’t even charged), about the materiality of other things, a number of which have nothing to do with the Carter Page FISA. Of particular note, the bulk (in terms of pages) of this indictment discusses lies that Durham doesn’t tie back to Carter Page, even though he could have, had he treated Olga Galkina differently.

-

-

- Danchenko’s lies were material because FBI relied on the dossier to obtain FISA warrants on Carter Page: “The FBI’ s investigation of the Trump Campaign relied in large part on the Company Reports to obtain FISA warrants on Advisor-1.”

- Danchenko’s lie about believing Millian called him in July 2016 because it formed the basis of the FISA applications targeting Page: Danchenko’s alleged lies to the FBI about Millian, “claiming to have received a late July 2016 anonymous phone call from an individual that DANCHENKO believed to be Chamber President-I were highly material to the FBI because, among other reasons, the allegations sourced to Chamber President-I by DANCHENKO formed the basis of a Company Report that, in turn, underpinned the aforementioned four FISA applications targeting a U.S. citizen (Advisor 1).”

- Danchenko’s lies were material because they made it harder for the FBI to vet the dossier: “The FBI ultimately devoted substantial resources attempting to investigate and corroborate the allegations contained in the Company Reports, including the reliability of DANCHENKO’s sub-sources.”

- Danchenko’s lies about how indiscreet he was about collecting information for Steele prevented the FBI from understanding whether people, including Russia, could inject disinformation into the dossier: Accordingly, DANCHENKO’s January 24, 2017 statements (i) that he never mentioned U .K. Person-I or U .K. Investigative Firm-I to his friends or associates and (ii) that “you [the FBI] are the first people he’s told,” were knowingly and intentionally false. In truth and in fact, and as DANCHENKO well knew, DANCHENKO had informed a number of individuals about his relationship with U.K. Person-I and U.K. Investigative Firm-I. Such lies were material to the FBI’ s ongoing investigation because, among other reasons, it was important for the FBI to understand how discreet or open DANCHENKO had been with his friends and associates about his status as an employee of U .K. Investigative Firm-I, since his practices in this regard could, in tum, affect the likelihood that other individuals – including hostile foreign intelligence services – would learn of and attempt to influence DANCHENKO’s reporting for U.K. Investigative Firm1.

- Dancheko’s lies about Charles Dolan prevented the FBI from learning that Dolan was well-connected in Russia, Dolan had ties to Hillary, and Danchenko gathered some of his information using access obtained through Dolan: DANCHENKO’s lies denying PR Executive-1 ‘s role in specific information referenced in the Company Reports were material to the FBI because, among other reasons, they deprived FBI agents and analysts of probative information concerning PR Executive-I that would have, among other things, assisted them in evaluating the credibility, reliability, and veracity of the Company Reports, including DANCHENKO’s sub-sources. In particular, PR Executive-I maintained connections to numerous people and events described in several other reports, and DANCHENKO gathered information that appeared in the Company Reports during the June Planning Trip and the October Conference. In addition, and as alleged below, certain allegations that DANCHENKO provided to U.K. Person-I, and which appeared in other Company Reports, mirrored and/or reflected information that PR Executive-I himself also had received through his own interactions with Russian nationals. As alleged below, all of these facts rendered DANCHENKO’s lies regarding PR Executive-1 ‘s role as a source of information for the Company Reports highly material to the FBI’ s ongoing investigation. [snip] PR Executive-1 ‘s role as a contributor of information to the Company Reports was highly relevant and material to the FBI’s evaluation of those reports because (a) PR Executive-I maintained pre-existing and ongoing relationships with numerous persons named or described in the Company Reports, including one of DANCHENKO’s Russian sub-sources ( detailed below), (b) PR Executive-I maintained historical and ongoing involvement in Democratic politics, which bore upon PR Executive-I’s reliability, motivations, and potential bias as a source of information for the Company Reports, and (c) DANCHENKO gathered some of the information contained in the Company Reports at events in Moscow organized by PR Executive-I and others that DANCHENKO attended at PR Executive-1 ‘s invitation. Indeed, and as alleged below, certain allegations that DANCHENKO provided to U.K. Person-I, and which appeared in the Company Reports, mirrored and/or reflected information that PR Executive-I himself also had received through his own interactions with Russian nationals.

- Danchenko’s lies about Dolan prevented the FBI from asking whether Dolan spoke to Danchenko about the Ritz Hotel: Based on the foregoing, DANCHENKO’s lies to the FBI denying that he had communicated with PR Executive-I regarding information in the Company Reports were highly material. Had DANCHENKO accurately disclosed to FBI agents that PR Executive-I was a source for specific information in the aforementioned Company Reports regarding Campaign Manager-1 ‘s departure from the Trump campaign, see Paragraphs 45-57, supra, the FBI might have taken further investigative steps to, among other things, interview PR Executive-I about (i) the June 2016 Planning Trip, (ii) whether PR Executive-I spoke with DANCHENKO about Trump’s stay and alleged activity in the Presidential Suite of the Moscow Hotel, and (iii) PR Executive-1 ‘s interactions with General Manager-I and other Moscow Hotel staff. In sum, given that PR Executive-I was present at places and events where DANCHENKO collected information for the Company Reports, DANCHENKO’s subsequent lie about PR Executive-1 ‘s connection to the Company Reports was highly material to the FBI’ s investigation of these matters.

- Danchenko’s lies about Dolan prevented the FBI from asking Dolan whether he knew about a Russian Diplomat being reassigned from the US Embassy: Based on the foregoing, DANCHENKO’s lies to the FBI denying that he had communicated with PR Executive-I regarding information in the Company Reports were highly material. Had DANCHENKO accurately disclosed to FBI agents that PR Executive-I was a source for specific information in the Company Reports regarding Campaign Manager-I ‘s departure from the Trump campaign, see Paragraphs 45-57, supra, the FBI might also have taken further investigative steps to, among other things, interview PR Executive-I regarding his potential knowledge of Russian Diplomat-1 ‘s departure from the United States. Such investigative steps might have assisted the FBI in resolving the above-described discrepancy between DANCHENKO and U.K. Person-I regarding the sourcing of the allegation concerning Russian Diplomat-I.

- Danchenko’s lies about Dolan prevented the FBI from asking whether Dolan was the source for the [true] report about reasons why Paul Manafort had left the Trump campaign: Based on the foregoing, DANCHENKO’s lie to the FBI about PR Executive-I not providing information contained in the Company Reports was highly material. Had DANCHENKO accurately disclosed to FBI agents that PR Executive-I was a source for specific information in the aforementioned Company Reports regarding Campaign Manager-I’s departure from the Trump campaign, see Paragraphs 45-57, supra, the FBI might have taken further investigative steps to, among other things, interview PR Executive-I regarding his potential knowledge of additional allegations in the Company Reports regarding Russian Chief of Staff-I. Such investigative steps might have, among other things, assisted the FBI in determining whether PR Executive-I was one of DANCHENKO’s “other friends” who provided the aforementioned information regarding Putin’s firing of Russian Chief of Staff-I.

- Danchenko’s lies about a phone call made it harder for the FBI to vet the dossier: Danchenko’s alleged lies about Millian were material because, “at all times relevant to this Indictment, the FBI continued its attempts to analyze, vet, and corroborate the information in the Company Report.”

- The FBI took and did not take certain actions because of Danchenko’s lies: “The Company Reports, as well as information collected for the Reports by DANCHENKO, played a role in the FBI’s investigative decisions and in sworn representations that the FBI made to the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court throughout the relevant time period.”

- Danchenko’s alleged lies about Millian affected both FBI’s investigative decisions and played a role in their FISA applications: They “played a key role in the FBI’s investigative decisions and in sworn representations that the FBI made to the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court throughout the relevant time period.”

Sources

DOJ IG Report on Carter Page

Mueller Report

October 2016 Page FISA Application

January 2017 Page FISA Application

April 2017 Page FISA Application

June 2017 Page FISA Application

Dossier vetting spreadsheet

Danchenko posts

The Igor Danchenko Indictment: Structure

John Durham May Have Made Igor Danchenko “Aggrieved” Under FISA

“Yes and No:” John Durham Confuses Networking with Intelligence Collection

Daisy-Chain: The FBI Appears to Have Asked Danchenko Whether Dolan Was a Source for Steele, Not Danchenko

Source 6A: John Durham’s Twitter Charges

John Durham: Destroying the Purported Victims to Save Them

John Durham’s Cut-and-Paste Failures — and Other Indices of Unreliability

Aleksej Gubarev Drops Lawsuit after DOJ Confirms Steele Dossier Report Naming Gubarev’s Company Came from His Employee

In Story Purporting to “Reckon” with Steele’s Baseless Insinuations, CNN Spreads Durham’s Unsubstantiated Insinuations

On CIPA and Sequestration: Durham’s Discovery Deadends

The Disinformation that Got Told: Michael Cohen Was, in Fact, Hiding Secret Communications with the Kremlin

An intelligence report related to the second story hung on the laptop, regarding Hunter’s ties to China, was disclosed to have been attributed to an intelligence analyst whose identity was entirely fabricated, down to his artificially generated face. And the IC’s report on efforts to interfere in the 2020 election includes one conclusion that sounds suspiciously similar to the efforts that led to the laptop story.

An intelligence report related to the second story hung on the laptop, regarding Hunter’s ties to China, was disclosed to have been attributed to an intelligence analyst whose identity was entirely fabricated, down to his artificially generated face. And the IC’s report on efforts to interfere in the 2020 election includes one conclusion that sounds suspiciously similar to the efforts that led to the laptop story.