How Rick Gates Used Maggie Haberman and Ken Vogel

Last week, DOJ released a reprocessed set of most of Rick Gates’ 302s in Jason Leopold’s FOIA for Mueller materials. I used that as an opportunity to pull together all of his 302s to capture the content and pull out the materials withheld under b7A exemptions (b7A exemptions reflect ongoing investigations — though many of these are clearly just counterintelligence investigations into Ukraine’s attempts to influence US politics). I did the same thing for Steve Bannon, Mike Flynn, and Sam Patten’s files.

Reading all the 302s like this shows this, at times, Gates went wobbly on Mueller’s team. And it provides yet more evidence that a NYT article — bylined by two reporters that came up in Gates’ interviews, Maggie Haberman and Ken Vogel — was a (wildly successful) attempt to misrepresent how damning were Gates’ admissions about Paul Manafort’s efforts to provide ongoing campaign updates to Russian intelligence officer Konstantin Kilimnik.

Nevertheless, the NYT has never issued a correction.

It’s not news that Gates went wobbly on his cooperation. Andrew Weissmann described the beginning process of this in his book, Where the Law Ends. But the 302s suggest it was not a one-time event.

As Weissmann told it in his book published before all the 302s came out, in one of his first proffers, Gates told prosecutors that he himself was skimming money from Manafort.

Gates said he understood and, from there, we began in earnest, alternating between Gates admitting his guilt for the crimes he and Manafort had committed and our teasing out information he had about others. This can be an awkward dance, but Gates seemed to be forthcoming. For example, after walking us through how, precisely, he’d helped Manafort launder money from his offshore accounts, Gates explained that he’d also personally stolen money from Ukraine by inflating the invoices he submitted for their political consulting work then pocketing that excess cash. Gates had never told Manafort about this skimming, he said, or reported that extra income on his taxes. We hadn’t known about this—it was new information, and encouraging, since it signaled that Gates understood that he could not hide or minimize his own criminality anymore.

That may have happened in his first interview, on January 29, 2018, when he described diverting income from his DMP work to an account in London.

Having gotten Gates to admit cheating Manafort, Weissmann then turned to what he called a “Jackpot” moment, when Gates described two things: that, at the August 2 meeting in the Havana Room, Manafort had told Kilimnik how he planned to win the campaign (a question Weissmann’s team was obsessed with understanding), and also that Manafort had ordered Gates to send Konstantin Kilimnik polling data throughout the campaign (of which Mueller’s team did not have prior knowledge).

“I learned of that meeting on the same day that it happened,” Gates explained. “Paul asked if I could join him and ‘KK,’ ” as Gates called Kilimnik. “The meeting was supposed to be over dinner, but I got there late.”

I did not look over at Omer, but I knew he was thinking what I was, that it was good that Gates was being forthright so far and confirming what we knew.

“Do you know how long they had already been there?” I asked.

“I don’t, but I think I was fairly late getting there. They were well into the meal.”

“What do you recall being discussed?” Omer asked. “A few things,” Gates explained. One subject was money—certain oligarchs in Ukraine still owed Manafort a considerable amount. Another was a legal dispute between Manafort and the Russian oligarch Oleg Deripaska. We asked Gates if there was any new or unusual information raised about these issues, but he said no—those problems had been percolating for a while. This was not, it seemed, enough of a reason for Kilimnik to come to New York from Moscow.

“What else do you recall being discussed?” Omer asked.

“There was discussion about the campaign,” Gates said. “Paul told KK about his strategy to go after white working-class Democrats in general, and he discussed four battleground states and polling.”

“Did he name any states?” I asked.

“Michigan, Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, and Minnesota,” Gates said.

“Did he specifically mention those states, and did he describe them as battleground states, or is that your description?” I asked.

“No,” Gates said. “Paul described them that way. And, yes, I remember those four states coming up.”

“And he described polling?” Omer asked.

“Yes, but I had been sending our internal polling data to KK all along,” Gates explained. “So this was a follow-up on that, as opposed to something out of the blue.”

“I’m sorry,” I said, “but why were you sending polling data to Kilimnik?”

“Paul told me to send him the data, periodically. So I did. I’d send it using WhatsApp or some other encrypted platform. I assume it was to help Paul financially. I just did what Paul told me to do.”

“KK didn’t have any position on the campaign, right?” I asked.

The 302 from that same first interview shows Gates raised Manafort’s election year meetings with Kilimnik, though he got some details wrong, as I’ll return to. Gates addressed the Havana Bar meeting in his second interview, too, though he continued to tell an implausible story.

In his third interview, Gates attempted to lie about whether he had deleted documents; after a long discussion (still redacted because of an ongoing investigation), Gates admitted “maybe” he had deleted documents after learning of Mueller’s investigation.

In the fourth interview (at which Gates referenced false claims floated in the press to suggest the Mueller investigation had dodgy beginnings), Gates attempted to hide that he had lied to Mercury Public Affairs and Podesta Group about who their Ukrainian client really was, only to admit that “overtime” he realized what he had told them was not truthful; ultimately he admitted that “we got cute” by registering (and getting Podesta Group to register) under the Lobbying Disclosure Act and not FARA. At least as recorded in the 302, that’s the interview where Gates first lied about a meeting Manafort had with Dana Rohrabacher. At the same interview, Gates’ lawyer, Tom Green (who is a friend of Mueller’s), made a statement attributing Gates’ failures to keep certain lobbying documents to DMP archiving policy; in his statement of offense, Manafort admitted he still had those documents when he submitted his lobbying filings.

Weissmann’s book describes catching Gates in the lie about Rohrabacher.

Not long after I reentered the room, our interview with Gates turned to the FARA charges. Gates explained, in a convoluted fashion, that he and Manafort had believed there was no need to register under FARA since they were not personally doing any of the lobbying themselves. Manafort understood now that the law required him to file, Gates said, but he hadn’t understood that at the time.

Nothing about this argument was credible. Manafort was not only a longtime lobbyist but an attorney himself; he had extensive experience navigating the FARA rules and had gotten entangled with the FARA Unit before. (In the eighties, Manafort had a presidential appointment in the Reagan administration, which normally would have prohibited him from also working as a lobbyist, but he’d requested a waiver from that facet of the FARA rules. Interestingly, when his request was denied by a responsible White House attorney, Manafort resigned from his public office in order to continue the more profitable private lobbying work.) We had even uncovered an email from Gates to Manafort that clearly set out the FARA regulations. It was inconceivable that they’d misunderstood the law. Even the factual premise of their purported misunderstanding was untrue: Manafort had personally acted as a lobbyist. We had emails showing that Gates had arranged a meeting for Manafort with the pro-Russia California congressman Dana Rohrabacher in March 2013, shortly after Rohrabacher became chair of the subcommittee that oversaw Ukraine issues.

It was clear that Gates was not being straight with us—not uncommon, initially, with people who try to cooperate; they tell the truth with various degrees of success at first. When we confronted Gates with the emails about the Rohrabacher meeting, Gates simply doubled down, floating an even more absurd claim. He acknowledged that, yes, Manafort and Rohrabacher had met in Washington in 2013, but Gates claimed that he remembered Manafort telling him at the time that the subject of Ukraine had never come up—and therefore, there’d been no reason for Manafort to register under FARA for this activity: It wasn’t actually lobbying.

This wasn’t true, either, and we had evidence to prove it. Gates and Manafort had prepared a memo after the Rohrabacher meeting for President Yanukovych of Ukraine, summarizing the discussion. That memo was one of the many damning documents we’d discovered from Manafort’s condo search. We showed it to Gates: Was everything written here a lie? we asked. He had no response.

Gates’s story was crumbling before our eyes. It was infuriating because it was so counterproductive for everyone, and, on a personal level, displayed a certain contempt for us, and a low opinion of our ability to discern the truth. The good faith we needed, on both sides, was evaporating.

I asked Tom Green, Gates’s counsel, to speak in private, and then decided with him that we should break for the day. I asked Tom to get to the bottom of whatever was happening. All along, Gates had seemed to have trouble when it came to discussing Manafort and his crimes. He was clearly straining to shed his allegiance to his old boss. Still, Gates was discussing his own crimes, and it wasn’t clear why he’d chosen to start lying, so stubbornly, now, about this particular point; the FARA charges weren’t even among the most serious ones we brought.

If there was some explanation, Tom would need to figure it out quickly. The lies we’d just been told were deflating for us, given how hopeful we’d been about Gates’s usefulness as a witness.

Right now, we told Tom, there was no way we could sign Gates up.

Ultimately, Gates would plead guilty to this lie about Rohrabacher as a separate false statement.

The next day, according to Weissmann’s book, Green had seemingly gotten Gates back on track.

Tom came back to our office the next day. “Look,” he said, “my client messed up.”

Gates was scared, he explained. This entire process was wrenching for him. Gates felt pulled between his desire to cooperate and his allegiance to Manafort, and his client had just momentarily broken down. He’d fed us the various cover stories yesterday to avoid implicating Paul on the FARA charges.

In his book, Weissmann doesn’t reflect on the other lies that Gates must have told before his team caught Gates in a lie they could prove was one. But Gates’ earlier testimony does conflict with what he would say later.

And even having recommitted to cooperating, it seems Gates was still shading the truth in those February sessions, at least until he actually pled guilty.

The released 302s show that on February 2, Gates admitted that they should have registered under FARA for the meeting with Rohrabacher. In the same interview, there are five pages discussing a redacted subject that remain exempted under a b7A (ongoing investigation) exemption. Even in that interview, even after admitting he was still on the DMP payroll in the months while everyone was trying to place Manafort on the Trump campaign, Gates offered implausible answers about why Manafort would ask him to provide updates to Oleg Deripaska in the guise of confirming a lawsuit that had been dismissed had been dismissed. Additionally, Gates explained away a briefing for Trump about Manafort’s ties to Ukraine as Manafort’s effort to have Gates prepared to answer press questions about the topic.

Importantly, given later admissions about Gates’ efforts to work the press, when asked about the emails with Kilimnik discussing campaign briefings that had been reported in the press the previous year, Gates claimed he hadn’t spoken to Manafort about those reports. Then, having claimed he and Manafort hadn’t concocted a cover story about them, he claimed that they were references to Deripaska’s lawsuit.

Gates was shown an email thread between Kilimnik and Manafort dated July 7, 2016 through July 29, 2016.

Gates stated he saw some of these email[s] in the news. Gates did not talk to Manafort about the emails when they were leaked to the press. In July 2016, the topic of conversation with Manafort was the Deripaska lawsuit.

But then shortly after, in the very same interview, Gates described talking to Manafort about the emails.

When this email came out in the news, Manafort told Gates, Brad Parscale and [redacted] that the article was “B.S.”

That is, Gates claimed not to have spoken to Manafort about the news, but then described doing just that, and based on that inconsistent claim, asserted that the emails about providing campaign briefings to Deripaska pertained to the lawsuit with the Russian oligarch.

In this interview where Gates was clearly trying to shade the truth, he nevertheless still admitted sending “confidential polling data derived from internal polls” to Kilimnik.

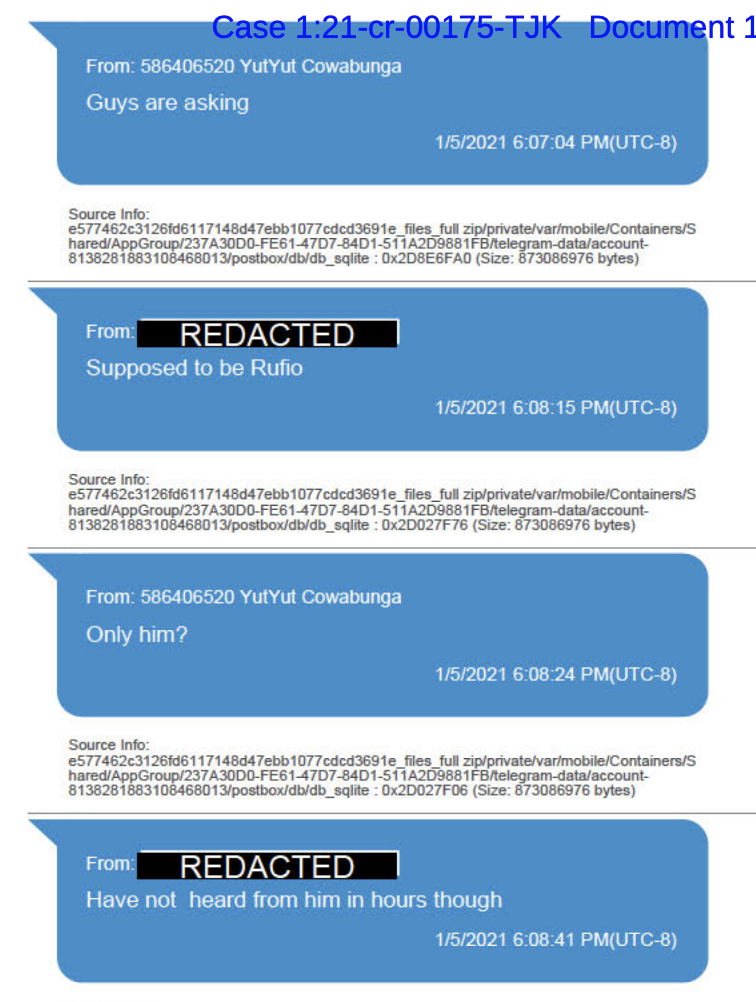

On February 7, Gates had his first interview with another Mueller team, the Russian team led by Jeannie Rhee. The interview largely focused on the role of Dmitri Simes had in Trump’s first foreign policy speech, and touched briefly on the various views people had about sanctions on Russia.

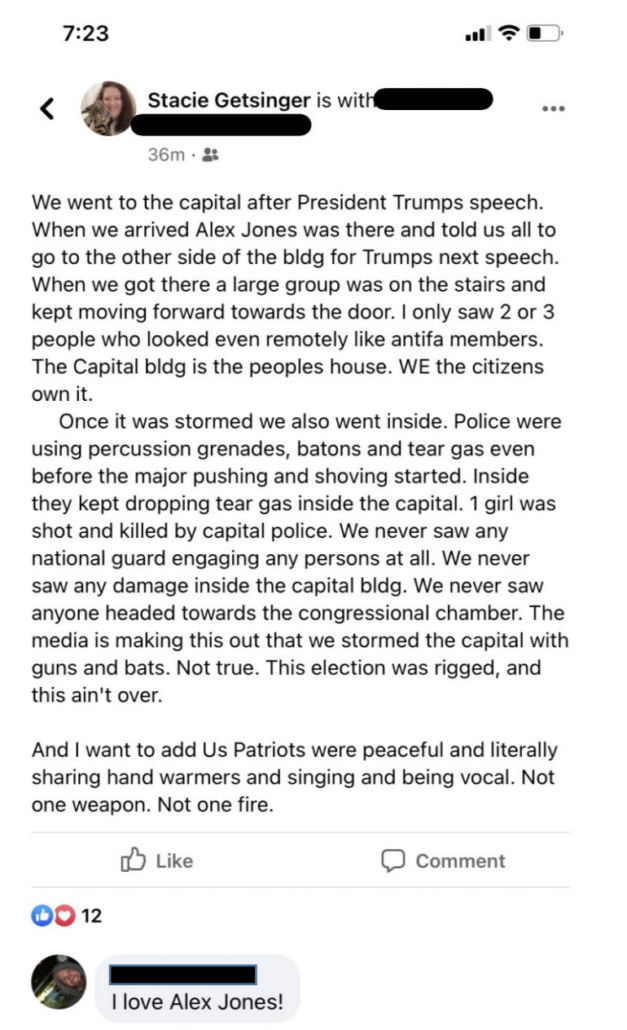

Even though the Mueller team would eventually obtain evidence that Roger Stone tried to influence this process through Gates, Gates never mentioned how he personally released news of the speech through Maggie Haberman as a way to inform Stone about it, effectively using Maggie as a vehicle to communicate with someone, Stone, whom Manafort treated as part of his team while hiding those direct ties.

On April 22, 2016, Maggie Haberman broke the news that Donald Trump would give a foreign policy speech. As she reported, the speech was scheduled to be held at the National Press Club and would be hosted by the Center for National Interest, a group that once had ties to the Richard Nixon Library.

Donald J. Trump will deliver his first foreign policy address at the National Press Club in Washington next week, his campaign said, at an event hosted by an organization founded by President Richard M. Nixon.

The speech, planned for lunchtime on Wednesday, will be Mr. Trump’s first major policy address since a national security speech last fall.

The speech will be hosted by the Center for the National Interest, formerly known as the Nixon Center, and the magazine it publishes, The National Interest, according to a news release provided by the Trump campaign.

The group, which left the Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum in 2011 to become a nonprofit, says on its website that it was founded by the former president to be a voice to promote “strategic realism in U.S. foreign policy.” Its associates include Henry A. Kissinger, the secretary of state under Nixon, as well as Senator Jeff Sessions, Republican of Alabama and a senior adviser to Mr. Trump. Roger Stone, a sometime adviser of Mr. Trump, is a former Nixon aide.

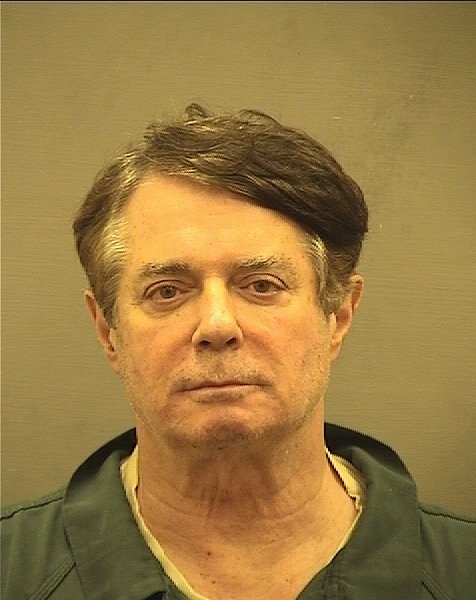

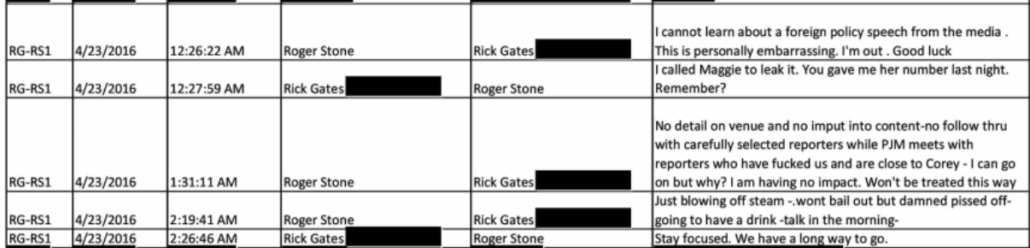

That night, according to texts released during his trial, Roger Stone wrote Rick Gates, furious that he had not been consulted about the details of the speech first — though Gates explained that he leaked it to Haberman so Stone would find out. “I cannot learn about a foreign policy speech from the media,” Trump’s rat-fucker said. “This is personally embarrassing. I’m out,” said the advisor who had supposedly quit the campaign almost a year earlier.

Among the things Stone bitched about learning from a leak to Maggie Haberman made partly for his benefit was about the venue. “No detail on venue and no input on content.”

In that same interview where Gates did not disclose Stone’s demand that he get a say on Trump’s foreign policy speeches, he nevertheless reiterated his admission that, “Gates sent Kilimnik both publicly available information and internal information from Fabrizio’s polls.” Gates also provided a description of Cambridge Analytica in the poll mix, though his descriptions of the campaign’s reliance on CA would remain inconsistent through the entirety of his cooperation with Mueller’s team.

Over the next two meetings, things seemed to get closer to finalizing the plea. In an interview on February 9, Gates further elaborated on why he had lied about the meeting with Rohrabacher. Prosecutors also got him on the record on an instance where he gave family members advance information about the acquisition of ID Watchdog, a company he had a stake in, by Equifax. Then in the following interview, Mueller’s team went through one after another crime he may have committed — insider trading (with IDW), bank fraud, bribery, “lack of candor under oath,” including during his 2014 FBI interview and the Skadden Report, campaign fraud, obstruction of justice, all of which would need to be on the record before he pled guilty.

After doing that, prosecutors got Gates on the record about key Mueller-related topics about which they wanted his cooperation, including Stone and Thomas Barrack. In their review of Gates’ description of the August 2 meeting, he confirmed that Deripaska was discussed (though claimed he only knew polling data was shared with the Ukrainian paymasters), and provided a really sketchy explanation of what this was all about:

Gates was asked why Kilimnik referred to Manafort’s “clever plan to defeat” Hillary Clinton in an email. Gates believed this referred to Manafort’s strategy to attack Clinton’s credibility. Gates was asked what was “clever” about this. Gates agreed that it was not clever and he did not know why Kilimnik characterized it as clever.

Gates did not trust Kilimnik. Gates did not know why Manafort was sharing internal polling data with Kilimnik. Gates said Kilimnik could have given the information to anyone.

That’s when the plea deal should have been finalized. But as Weissmann described in his book, it wasn’t.

Gates’ prior attorney (who was also representing someone else against whom Gates would testify), in the guise of demanding past payment, caused a sealed conference to be held before Amy Berman Jackson which alerted the press that he might be cooperating, which in turn generated a great deal of pressure on Gates not to flip (including the involvement of Sean Hannity). From Weissmann again:

But before we received the final versions back, with signatures, the process was disrupted yet again. Gates’s second defense counsel, Walter Mack, called our office unexpectedly and asked what the heck was going on: Was it true that his client was cooperating with the special counsel’s investigation?

It’s hard to convey the strangeness of Walter’s phone call: not only that he didn’t seem to know that Gates was seeking to cooperate, but that he was calling us for answers, instead of asking his own client, or his co-counsel Tom Green. We told Walter that he should direct those questions to Gates or Tom. It was not our place to be an intermediary between defendants and their various attorneys, or to mediate whatever spat Walter had just brought to our doorstep.

I’m still not sure what was going on behind the scenes. Later, Walter would claim a lack of payment from Gates—maybe that had something to do with it. But it was also hard to ignore that Walter happened to be simultaneously representing a man named Steven Brown in a separate case in New York. Brown had enlisted Gates in a fraudulent scheme and therefore could be harmed by information Gates might share if he cooperated.

Regardless, whatever dispute was playing out might have remained irrelevant to our case—except that Walter’s subsequent discussions with Tom apparently unraveled to the point that Walter filed a motion asking to be relieved as Gates’s counsel; this required all of us to appear briefly in court. The short proceeding had very little to do with our office and was under seal at the time, but our mere appearance at the courthouse roused interest from the reporters staking out the building. At the proceeding, the court told Tom to brief Walter on the cooperation progress. Shortly thereafter, someone leaked a story about Gates and his intention to cooperate to the Los Angeles Times.

This media attention was unsettling for Gates—as whoever leaked the story presumably knew it would be. It is hard enough to betray your former mentor, and walk away from your former life, by talking to government investigators. It is more daunting once you’ve seen your decision to cooperate spelled out in a national headline and are forced to discuss it with every friend and family member who calls to ask you if it’s true. Such press also sends out an alarm to those who’d seek to pull Gates back in line and away from the government.

As we feared, once the story ran, Gates got cold feet. Tom and I spoke nearly every day for the next two weeks. He explained that he was still working to convince his client to cooperate, and I expressed bafflement. I’d never seen anything like this before. Gates had passed the point of no return; because he’d already signed the proffer agreement and admitted his criminal liability to all of the charged crimes (and then some), he would be going to trial with effectively no defense if he backed out now. Tom assured me that Gates understood this—but he also said that Gates had lots of people loyal to the White House whispering in his ear.

So prosecutors drew up a second indictment against Manafort and Gates in Virginia. That, plus some advice from Charlie Black, may have been enough to get him back on board.

This time it seemed real. “He’s coming to my office to sign the papers right now,” Tom said.

I was relieved, but still skeptical. I told Tom I’d need to see him and Gates in our office again, to hear Gates explain what the hell had just happened. I also alerted him that we were, at that moment, pushing forward with our indictment in Virginia and, because the courthouse there didn’t allow phones or electronic devices, there was no way for me to call the prosecutors and stop it. Still, I assured Tom, this wouldn’t affect our deal: If Gates proved trustworthy, we’d move to dismiss this second set of charges in Virginia without prejudice and proceed in Washington as planned.

Gates came back into our office the next day. I leveled with him: “I’ve never had this experience before, and I need to understand what happened,” I said. “Why did you balk at the last minute? What’s going on?”

He seemed more vulnerable this time. He explained the intense pressure that Manafort and others were putting on him not to cooperate, how Manafort had told him that money could be raised to defray their legal expenses, and that the White House had their backs—code, Gates knew, to keep quiet and hold out for a pardon.

But, Gates went on, he’d also spoken to Charlie Black. Black had been in business with Manafort years ago, at the firm Black, Manafort, Stone and Kelly, then gone on to become a dean of Republican Party strategists and enjoyed a sterling reputation. (In a masterstroke, it turned out, at a moment when Tom was almost out of ideas, he had recruited Black to reach out to Gates and offer advice.) Black told Gates that, were he in a similar predicament, he would cooperate. Gates wasn’t an old man like Black and Manafort, Black explained; he needed to think about himself and his young family. And moreover, Black insisted, Gates would be foolish to count on a pardon. Trump was too self-absorbed to be dependable.

“I took this all in,” Gates said, “and I decided to follow Black’s advice.” Black’s encouragement seemed to have finally empowered Gates to turn on his old boss. “I know there’s a possibility that Paul will get a pardon in the end, and I’ll have to watch him walk free. But I decided I just have to deal with what I’ve done, and own what I have done.” He’d broken the law, he said. He needed to deal with the consequences now and do right by his family.

The first interviews after Gates pled guilty focused on this process, eliciting descriptions of all the people Gates had spoken to in prior days, including the Black conversation, three conversations where Manfort tried to find money to pay Gates’ legal bills, and others. A pardon came up but no one told him he would be pardoned. Someone also tried to help Gates find what would have been his fourth defense team. Gates explained that he had been told the Nunes Memo and the IG Report on the Hillary investigation would change the climate for his defense.

But after that, things started to move forward. Investigators got a list of all the encrypted comms Gates had used and those he knew Manafort had used. Then they began to turn back to all the Manafort graft Gates would help prosecutors untangle.

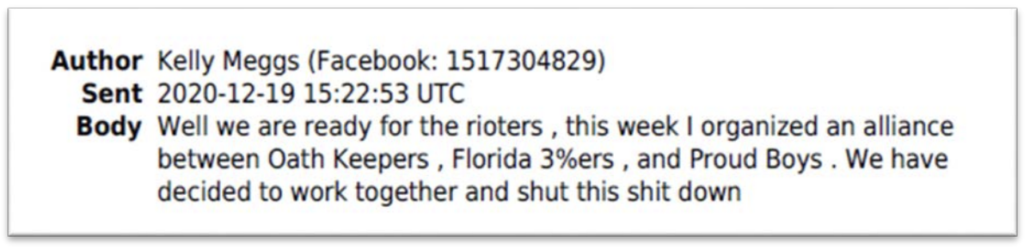

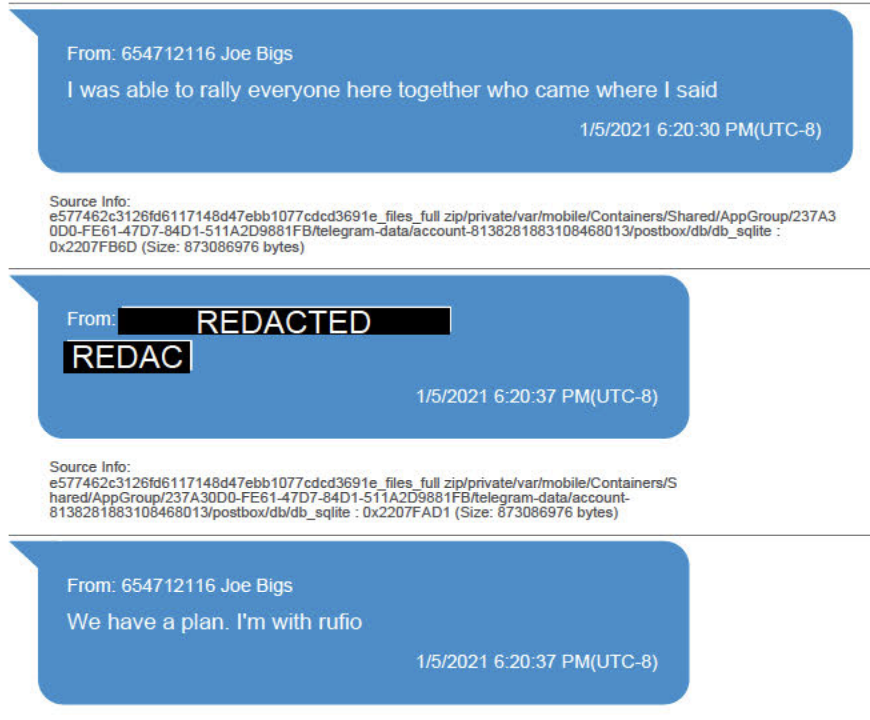

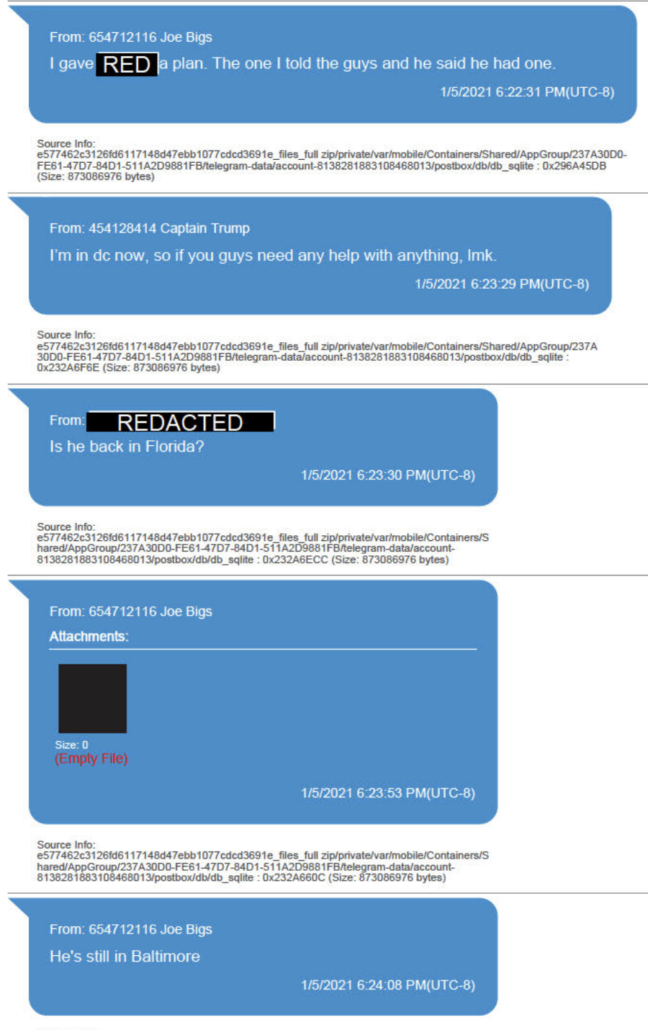

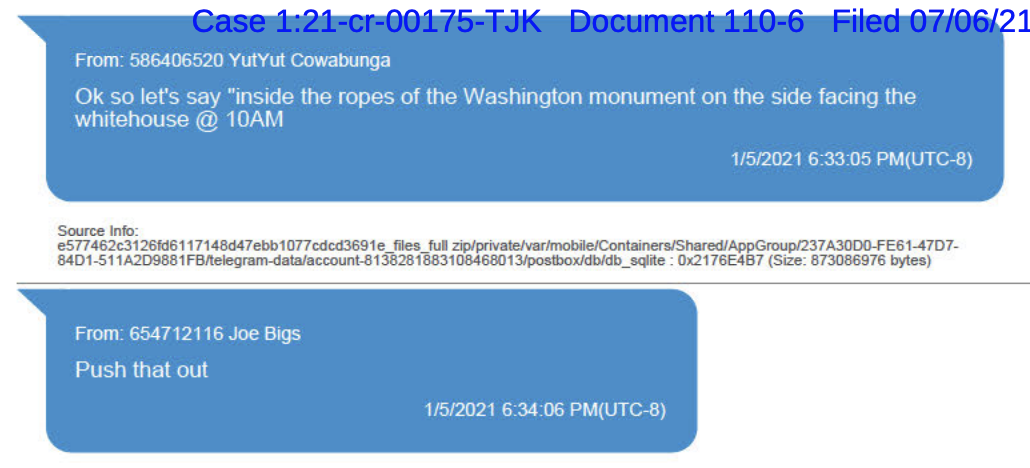

On March 1 — the first time prosecutors would return to two key Russia-related issues after Gates pled guilty, the August 2 meeting and Roger Stone — Gates revealed that he had lied to Ken Vogel in 2016 (who was then with Politico) about the Havana Club meeting. Gates started by (improbably) claiming he had never before read the June 19, 2017 WaPo story in which Konstantin Kilimnik provided a cover story for the August 2 meeting. That led him to admit lying to Vogel because he believed they’d get away without disclosing the meeting.

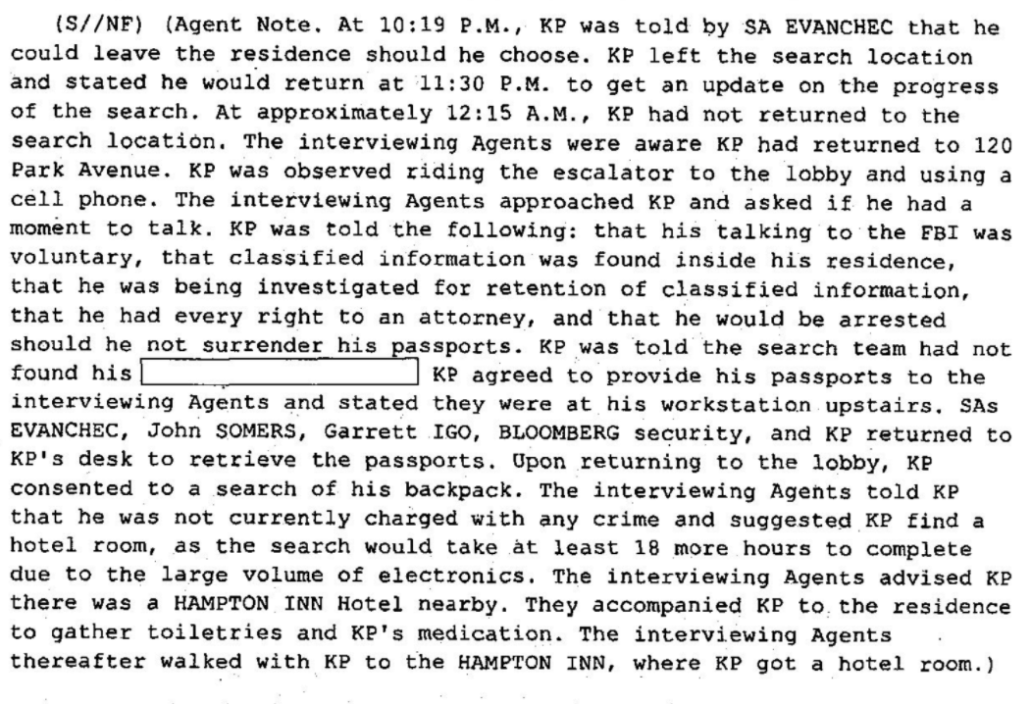

Gates stated that he hadn’t previously read the 6/19/2017 Washington Post article, which contained a statement from Konstantin Kilimnik regarding a meeting held in New York on 8/2/2016. Gates stated that following the 8/2/2016 meeting (which was held at New York’s Havana Club), Gates spoke to Paul Manafort regarding a subsequent Politico story about it. The author of the Politico article, Kenneth Vogel, had emailed a list of questions to Manafort. Manafort forwarded these questions to Gates, who answered “no” to all the questions. Gates admitted that he lied to Vogel with these responses. He had been assured no one would find out about this meeting. Gates stated that Jared Kushner became angry following the Politico article, unsure as to why Manafort would have such a meeting.

Then Gates admitted that Manafort did ask him whether anyone called him about the meeting — something still redacted for ongoing investigation. Effectively, Gates admitted that he understood that Manafort expected him to lie about the meeting.

Remember, during precisely this period in 2016, Oleg Deripaska was playing a double game, making Manafort more vulnerable even while getting him to share campaign campaign information. Perhaps not unrelatedly, much of the next month of Rick Gates interviews in 2018 focused on the Pericles lawsuit that Deripaska used as leverage against Manafort to put him in that more vulnerable position.

A March 21 interview covering things like Roger Stone and Cambridge Analytica remains significantly redacted (including one b7A redaction covering the latter topic added since this 302 was last released).

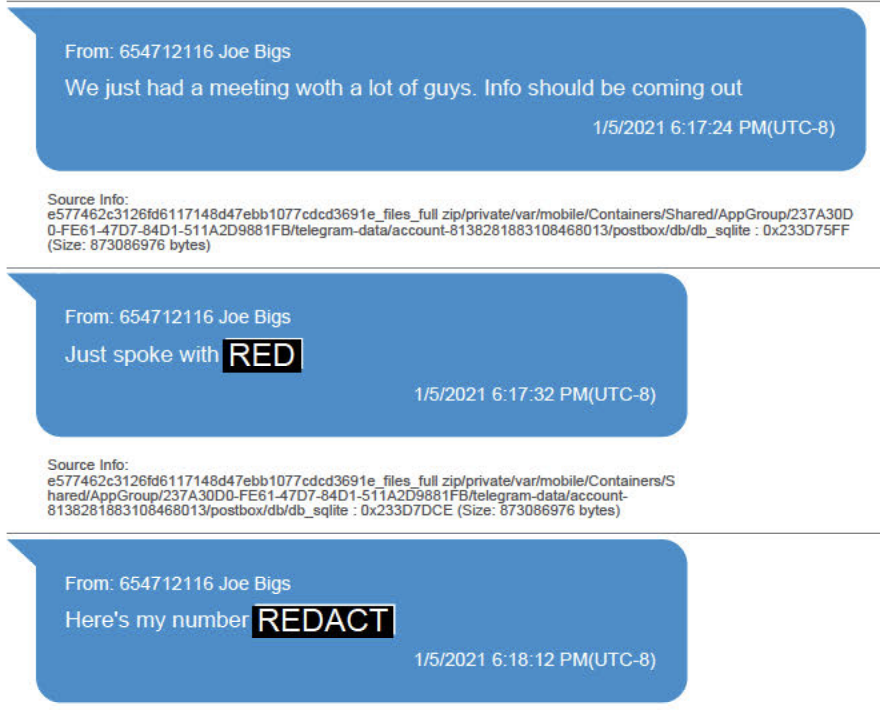

Something sort of interesting happened in April 2018. On two consecutive days, Gates told a slightly different story about Roger Stone. On April 10, Rhee and Aaron Zelinsky joined Manafort prosecutors Weissmann and Andres. At the beginning of the interview, Gates warned that someone was not happy he was cooperating. In the April 10 interview, Gates provided details about Stone’s ongoing relationship with Manafort that don’t appear, in unredacted form, elsewhere, as well as details of calls and meetings from June (these communications were a focus at Stone’s trial). Gates revealed that the day before Stone’s “Podesta time in the barrel” comment on August 21, 2016, Manafort told Gates Stone had told him the emails would come out (this is consistent with at least one of Manafort’s interviews). One subtext of this interview is that the means by which Lewandowski got fired in June was related to Stone’s bid to get Hillary’s emails.

In the April 10 interview, Gates described a June 15, 2016 phone call he had with Manafort and Stone where Stone said “he had been in contact with Guccifer 2.” The FBI spent much of 2018 trying to track down forensic proof that this had indeed happen.

In the same interview, Gates asserted that Manafort,

always intended to use Stone as an outside source of information. Manafort relied on Stone to do operative work and dig up opposition material. Manafort had conveyed to Gates that Stone was in the hunt for Clinton’s emails prior to the Crowdstrike report dated 06/14/2016 announcement. Stone told Gates and Manafort something major was going to happen and that a leak of information was coming.

All told this may be Gates’ most revelatory interview about Stone.

But an April 11 interview, which covers the same issues (and at which Rhee was not present), seems to back off the claim that Manafort was pushing Stone to go get the emails. “[N]o one told Stone to go get” the emails Assange had. In a separate interview that same day (without the Stone team), Weissmann and Andres asked Gates about contacts he had had, though that seems to refer to contacts during 2017. On April 17, an interview seemed to focus on something Manafort had done.

Prosecutors kept asking about his contacts during the investigation (as they did with Mike Flynn during the same period). On May 3, Gates described with whom he had contact since his last interview (on April 19). That included two conversations with Maggie Haberman. Later in May, Gates was interviewed about his and Manafort’s response to an July 2016 AP report on Manfort’s Ukraine graft. In July, Gates revealed that, prior to pleading guilty, Manafort had warned Gates against his attorney Tom Green. In different July interview, Gates also described being in contact with people about a NYT report on him.

Gates’ plea deal required he get prior approval before he revealed any information derived from his cooperation to a third party. But he appears to have remained in touch with the NYT anyway.

In August, investigators grilled Gates about a topic that they hadn’t known about but which he had admitted on the stand while testifying in Paul Manafort’s trial: That he may have submitted a false expense report to the Inauguration Committee, replicating a theft that he had earlier used against Manafort. That discussion remains redacted under b7A redactions. It was not addressed in the government sentencing memo for Gates. It’s one potential crime Gates admitted only after entering into the plea agreement.

During fall interviews, Gates addressed additional investigative interest (such as the spin-off prosecutions arising from Manafort’s graft). He provided an interview on Stone on October 25 (the day before Steve Bannon would be interviewed and one of his last interviews before the election) that generally accorded with past testimony. And he did a few interviews pertaining to Kilimnik (parallel to the time when Manafort was being questioned about the same topic), including one where he reiterated that,

GATES understood that the polling data he was sending to KILIMNIK would be given to LYOVOCHKIN and DERIPASKA. GATES believed MANAFORT would have sent the polling data to LYOVOCHKIN as part of his efforts to get money out of Ukraine. GATES believed MANAFORT would have sent the polling data to DERIPASKA [redacted]. GATES opined that MANAFORT believed that Trump’s strength in the polls would be advantageous to him.

GATES provided KILIMNIK a mix of public polls and the campaign’s Fabrizio polling data based on what MANAFORT thought looked good. The Fabrizio polls were more reliable because they used cell phone polling data.

GATES provided certainly weekly data automatically to KILIMNIK. MANAFORT and GATES would send additional polling data on an ad hoc basis. On multiple occasions, GATES and MANAFORT would receive a poll and MANAFORT would tell GATES to send it to KILIMNIK based on the poll’s content.

That is, while there were conflicting details, after the time Gates started cooperating, his story about sharing polls repeatedly (though not always) acknowledged that Deripaska was receiving the polls. He consistently said the polls included non-public data (though his excuses for doing so varied from interview to interview and never offered a plausible explanation). And while he shifted the timeline earlier during the first interviews where he was telling other lies, after that point Gates never disputed that Manafort provided a more detailed explanation of his campaign strategy to Kilimnik, and he admitted his data sharing continued at least through the time Manafort left the campaign on August 19.

Gates’ description of what happened after that had some variances, as did his description of what polls were included in the sharing — but they always included Fabrizio’s polls, which, based on past work, they were the ones with which Kilimnik would be most familiar.

On November 7, the day Jeff Sessions would be fired, making way for Billy Barr to be nominated and confirmed, Gates did two interviews without his attorney, Tom Green, present.

There was, among the released interviews (there are about 60 that have been released, plus some other identified 302s that haven’t been), just one more in 2018.

Then, in advance of a February 15, 2019 interview, Gates’ attorney reached out to correct a claim that prosecutors had made as part of Manafort’s breach hearing. The important correction was that “GATES did not recall bringing [a document he had printed out earlier that day for a planning meeting] to the [Havana Bar] meeting. Gates affirmed, however, that,

At the 08/02/2016 meeting with GATES, MANAFORT, and KILIMNIK there was a much more detailed discussion of internal polling data compared to the data GATES sent to KILIMNIK via WHATSAPP. At the dinner meeting, GATES, MANAFORT, and KILIMNIK discussed internal polling from FABRIZIO which included battleground states.

[snip]

GATES recalled MANAFORT discussed internal polling from other sources including CAMBRIDGE ANALYTICA. The information provided in this meeting by MANAFORT to KILIMNIK was based on internal information and polls; it was a synthesis that included internal polling data.

In addition to the major correction regarding the document he printed out, however, Gates altered his testimony from many (though not all) of his previous interviews in one key way. At an interview the day after Billy Barr was confirmed as Attorney General and as Mueller’s team were already drafting their report, Gates reported that,

DERIPASKA was also in the mix. GATES recalled, however, that the letter to DERIPASKA was related to MANAFORT’s and DERIPASKA’s legal dispute. GATES does not specifically know if MANAFORT sent internal polling data to DERIPASKA.

That is, in his first interview after Barr became Attorney General, Gates backed off a claim that (at least per the 302s) he had made as recently as late October, that he knew he was sending Deripaska the polling data.

Then, on February 22, Gates had a last interview, by phone (there must have been one or several in advance of the Stone and Greg Craig trials). For a third time, his attorney — Robert Mueller’s friend Tom Green — was not present.

The topic of the interview, like so many before, was whom Gates had had contact with about the investigation. But of course, this time, key details of the investigation, especially about sharing polling data with Kilimnik, had been revealed by one of those redaction failures that sometimes happen at opportune times. Gates described someone “alert[ing] GATES to the allegation discussed above,” but claimed “their communication had no substance.” Before and after that, though, redacted answers that Gates offered seemed to deny speaking to anyone about the allegations, whether the inquiry pertained to comparing notes about answers with others involved — as Gates had denied then disproved happened in summer 2017 — or lying to the media to minimize damage — as Gates had admitted lying to Ken Vogel about the very same allegation.

And in spite of the fact that Weissmann warned Gates at least once not to say anything about his communications with Green, Gates ended the interview by addressing a claim his attorney seems to have made. “GATES stated that his counsel GREEN had been mistaken in indicating to the Special Counsel’s Office that GATES,” with a long paragraph describing what Green had told prosecutors but that Gates, with Green absent, was denying.

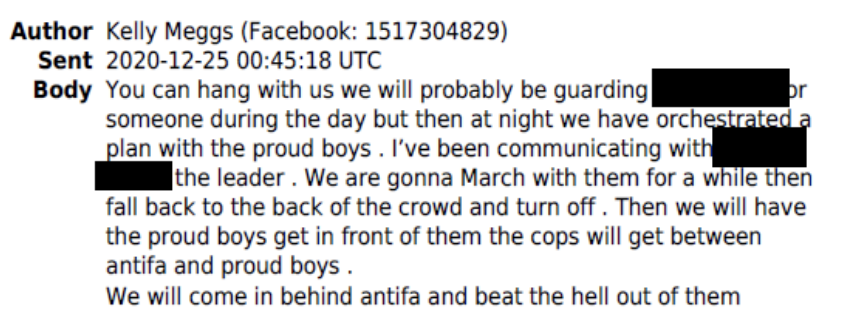

It turns out, though, that the demonstrably false story that NYT told resembled the ones Gates told in interviews where he was also lying about Rohrabacher, a year earlier. The NYT claimed that Gates had only transferred the data during the spring, not in August. It claimed “most of the data was public.” And it claimed Gates had only shared the data with two Ukrainian oligarchs, and not Oleg Deripaska.

Both Mr. Manafort and Rick Gates, the deputy campaign manager, transferred the data to Mr. Kilimnik in the spring of 2016 as Mr. Trump clinched the Republican presidential nomination, according to a person knowledgeable about the situation. Most of the data was public, but some of it was developed by a private polling firm working for the campaign, according to the person.

Mr. Manafort asked Mr. Gates to tell Mr. Kilimnik to pass the data to two Ukrainian oligarchs, Serhiy Lyovochkin and Rinat Akhmetov, the person said. The oligarchs had financed Russian-aligned Ukrainian political parties that had hired Mr. Manafort as a political consultant.

In his first interview, Gates claimed that the two Kilimnik meetings happened in spring, March and May. He further claimed the last time he spoke to Kilimnik was in May 2016, not that August meeting nor later attempts to craft a cover story for the Skadden Arps intervention. He offered another reason entirely for the meeting than sharing campaign data: Yanukovych wanted Manafort to run his next campaign.

In his second interview, Gates was told clearly the meeting at the Havana Bar happened in August, but then, when he began to admit to sharing campaign information, suggested Manafort had shared “Manafort’s plan for the primaries.” When reminded again that the meeting happened in August, long after Trump sealed up the nomination, Gates still persisted by claiming “they must have talked about the delegate issue and Manafort’s plan to get Trump enough delegates to win the nomination.” This interview appears to be the first time Gates offered the explanations he settled on for sharing campaign strategy — to get the Ukrainians to pay their bills and to get Deripaska to drop his law suit. But when investigators asked the obvious question — why Manafort wanted to share campaign information from someone he thought was Russian intelligence Gates claimed none of this was secret.

Gates was asked why Manafort would provide strategy information on the Trump Campaign to someone he thought was Russian Intelligence. Gates stated that the information on the battleground states and strategy was not secret.

This comment appears between passages redacted for ongoing investigation, so it’s not really clear whether the “he” here means Gates (who later would admit he suspected Kilimnik was a spy) And yet, he and Manafort spent a good deal of time obfuscating about doing just that.

Back in January 2018, before he started getting caught in deliberate lies, Gates was telling stories that shifted the time and the substance regarding why he and Manafort shared campaign data with Konstantin Kilimnik. And then, just as the Mueller team started preparing to write their conclusions, the NYT published a story that adopted the same time shift and subject obfuscations.

And in between, Rick Gates shared details repeatedly about how he used Maggie Haberman and Ken Vogel.