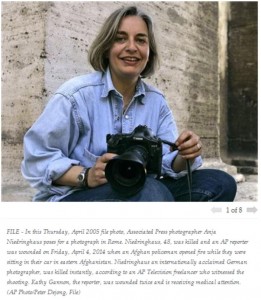

Afghan Policeman Kills AP Photographer Niedringhaus, Wounds Reporter Gannon

Yesterday, in noting the large deployment of Afghan security personnel for Saturday’s presidential election, I wondered in an aside how well these troops had been screened, since a large contingent of them were described in the Afghan press as “fresh”. Sadly, a police unit commander in the Tanai District on the outskirts of Khost turned his gun on a vehicle occupied by AP photographer Anje Niedringhaus and AP reporter Kathy Gannon. Niedringhaus was killed and Gannon is being treated for at least two bullet wounds but is said to be in stable condition. Early reports suggest that the police officer who opened fire was not a recent recruit and was taken into custody when he surrendered immediately after the incident.

AP provides details on Niedringhaus’ Pulitzer Prize-winning career:

Niedringhaus covered conflict zones including Kuwait, Iraq, Libya, Gaza and the West Bank during a 20-year stretch, beginning with the Balkans in the 1990s. She had traveled to Afghanistan numerous times since the 2001 U.S.-led invasion.

Niedringhaus, who also covers sports events around the globe, has received numerous awards for her works.

She was part of an AP team that won the 2005 Pulitzer Prize in breaking news photography for coverage of the war in Iraq, and was awarded the Courage in Journalism Award from the International Women’s Media Foundation. She joined the AP in 2002 and had since been based in Geneva, Switzerland. From 2006 to 2007, she was awarded a Nieman Fellowship in journalism at Harvard University.

Niedringhaus started her career as a freelance photographer for a local newspaper in her hometown in Hoexter, Germany at the age of 16. She worked for the European Press Photo Agency before joining the AP in 2002, based in Geneva. She had published two books.

Reporter Kathy Gannon is also experienced in war zones and Afghanistan particularly:

Gannon, 60, is a Canadian journalist based in Islamabad who has covered Afghanistan and Pakistan for the AP since mid-1980s.

She is a former Edward R. Murrow Fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations in New York and the author of a book on the country, “I Is for Infidel: From Holy War to Holy Terror: 18 Years Inside Afghanistan.”

The New York Times has one of the more complete descriptions of the attack that I have seen:

Ms. Niedringhaus and Ms. Gannon had spent Thursday night at the compound of the provincial governor in Khost, and had left on Friday morning with a convoy of election workers delivering ballots to an outlying area in the Tanai district, The A.P. and Afghan officials said.

The convoy was protected by the Afghan police, soldiers and operatives from the National Directorate of Security, Afghanistan’s main intelligence agency, said Mubarez Zadran, a spokesman for the provincial government. Ms. Niedringhaus and Ms. Gannon were in their own car, traveling with a driver and an Afghan freelance journalist who was working with the news agency.

After the convoy arrived at the government compound in Tanai, Ms. Niedringhaus and Ms. Gannon were waiting in the back seat for the convoy to start moving again when a police commander approached the car and looked through its windows. He apparently stepped away momentarily before wheeling around and shouting “Allahu akbar!” — God is great — and opening fire with an AK-47, witnesses and The A.P. said. His shots were all directed at the back seat.

Ms. Niedringhaus was killed instantly.

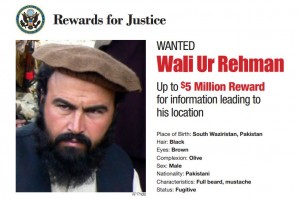

The police commander, identified by the authorities as Naqibullah, 50, then surrendered to other officers and was arrested. Witnesses said he was assigned to the force guarding the government compound and was not one of the officers traveling with the election convoy.

I have written extensively on the issue of green on blue killings, where Afghan forces attack US forces. It would appear that this is the first instance, though, of Afghan security personnel turning fire on Western members of the press. The Times addresses the insider killing aspect in relation to previous events: Read more →