John Bolton Versus Navy Versus Egan

John Bolton filed a motion opposing the government’s legal actions against him last night (it is both a memorandum in opposition to the Temporary Restraining Order as well as a motion to dismiss). It is particularly interesting because of some things Jack Goldsmith and Marty Lederman laid out in this post. As they note, the judge presiding over today’s hearing has no tolerance for Executive Branch bullshit, even on classified matters; the government’s own description of what happened raises lots of questions about regularity of the claim of classification, particularly as respects to whether there any compartmented information (SCI) remains in Bolton’s book; and the scrutiny of the government will be particularly stringent here, since it wants to censor something before publication.

This, however, might be a case in which a judge rejects or at least refuses to countenance the government’s classification decisions, at least for purposes of the requested injunction. That’s because of a confluence of unusual factors. They include:

- Several years ago, Judge Lamberth declared at a conference of federal employees that federal courts are “far too deferential” to the executive branch’s claims that certain information must be classified on national security grounds and shouldn’t be released to the public. Judges shouldn’t afford government officials “almost blind deference,” said Lamberth.

- The decision to classify material here appears to be highly irregular. The career official responsible for prepublication review at the National Security Council determined after a long process that Bolton’s manuscript contained no classified information. A political appointee who had only recently become a classifying authority, Ellis, then arrived at a different conclusion after only a brief review. It is even possible that Ellis classified information in Bolton’s manuscript for the first time after Bolton was told by Knight that the manuscript contained no classified information. At a minimum there were clearly process irregularities in the prepublication consideration of Bolton’s manuscript.

- The D.C. Circuit in dicta in McGehee stated that the government “would bear a much heavier burden” than the usual rationality review of executive branch classified information determinations in cases where the government seeks “an injunction against publication of censored items”—i.e., in a case like this one. Although it’s not clear whether that’s right, the First Amendment concerns raised by this case, in this setting, may affect how credulous Judge Lamberth is of the government’s classified information determinations and of the unusual way in which Bolton’s prepublication review was conducted.

Bolton’s motion answers a lot of questions that Goldsmith and Lederman asked in their post. For example, they ask whether Ellen Knight consulted with other top classification authorities before she verbally told Bolton the book had no more classified information in it; Bolton’s motion describes that on the call when Knight told Bolton the book had no more classified information, she, “cryptically replied that her ‘interaction’ with unnamed others in the White House about the book had ‘been very delicate,’ and that there were ‘some internal process considerations to work through.'”

Goldsmith and Lederman lay out a lot of questions contemplating the likelihood that Michael Ellis claimed the manuscript had SCI information after Knight informed Bolton that it had no more classified information, of any kind (remember, Ellis is likely the guy who moved Trump’s Ukraine transcript onto the compartmented server after people started raising concerns about it, so there would be precedent). Bolton’s brief lays out an extended description of why, if this indeed happened, it doesn’t matter with respect to the way his SCI non-disclosure agreement is written, because based on the record even the government presents, Bolton had no reason to believe the manuscript had SCI in it, and plenty of reason to believe it had no classified information of any type, when he instructed Simon & Schuster to move towards publication.

However, in its brief, the Government asserts for the first time that Ambassador Bolton’s book contains SCI and, therefore, that the SCI NDA applied to his manuscript and required that he receive written authorization from the NSC to publish it. See Doc. 3 at 12–14. This surprise assertion that the book contains SCI, even if true, would not alter the conclusion that the SCI NDA is inapplicable to this case.

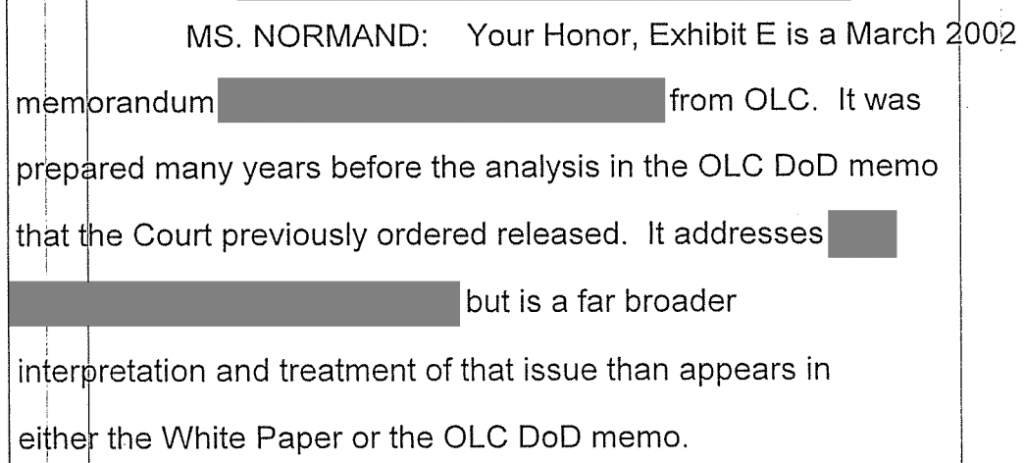

The Government is not painting on a blank canvas when it asserts that Ambassador Bolton’s book contains SCI. Rather, the Government’s assertion comes after a six-month course of dealing between the parties that informs whether and how the NDAs apply. See RESTATEMENT (SECOND) OF CONTRACTS § 202(4) (1981); see also id. § 223. Ambassador Bolton submitted his manuscript for prepublication review on December 30, 2019. Over the next four months, he (or his counsel) and Ms. Knight exchanged more than a dozen emails and letters, participated in numerous phone calls, and sat through more than a dozen hours of face-to-face meetings, painstakingly reviewing Ambassador Bolton’s manuscript. Yet, in all that time, Ms. Knight never asserted—or even hinted—that the manuscript contained SCI, even as she asserted that earlier drafts contained classified information. 102 After conducting an exhaustive process in which she reviewed the manuscript through least four waves of changes, Ms. Knight concluded that it contains no classified information—let alone SCI—as the Government concedes. Doc. 1 ¶ 46.

Nor did Mr. Eisenberg assert in either his June 8 or June 11 letters that the manuscript contains SCI. Nor did Mr. Ellis assert in his June 16 letter that the manuscript contains SCI. Indeed, not even the Government’s complaint asserted that the manuscript contains SCI, even as it specifically alleges that it contains “Confidential, Secret, and Top Secret” information. Doc. 1 ¶ 58. The first time that anyone in the Government so much as whispered that the manuscript contains SCI to either Ambassador Bolton or the public was yesterday, when the Government filed its motion. For nearly six months, it has been common ground between the NSC and Ambassador Bolton that his manuscript does not contain SCI. Only now, on the eve of the book’s publication and in service of seeking a prior restraint, has the Government brought forth this allegation.

And here is the key point: Ambassador Bolton authorized Simon & Schuster to publish his manuscript weeks ago, not long after receiving Ms. Knight’s confirmation that the book did not contain classified information and long before the Government’s first assertion yesterday that the book contained SCI. 103 Thus, at the time Ambassador Bolton proceeded with publishing his book—a decision that has long-since become irrevocable—he had absolutely no reason to believe that the book contained SCI. Indeed, quite the opposite: the Government had given him every reason to believe that it agreed with him that the book did not contain SCI. And if the book did not contain SCI, the SCI NDA did not apply when Ambassador Bolton authorized the book’s publication.

Yet the Government now argues that the SCI NDA did apply based on its discovery of alleged SCI six months after the prepublication-review process began. If that argument is sustained—if, that is, an author may be held liable under the SCI NDA even though neither the author nor the Government believed that the author’s writing contained SCI through four months of exhaustive prepublication review—it would mean that any federal employee who signs the SCI NDA would have no choice but to submit any writing, and certainly any writing that could even theoretically contain SCI, and then await written authorization before publishing that writing. The risk of liability would simply be too great for any author to proceed with publishing even a writing that both he and the official in charge of prepublication review believe, in good faith, is not subject to the SCI NDA.

What Goldsmith and Lederman don’t address — but Bolton does at length in his brief — is the role of the President in these matters. Bolton lays out (as many litigants against the President have before) abundant evidence that the President was retaliating here, including by redefining as highly classified any conversation with him at a very late stage in this process.

Yet, the evidence is overwhelming that the Government’s assertion that the manuscript contains classified information, like the corrupted prepublication review process that preceded it, is pretextual and in bad faith:

- On January 29, the President tweeted that Ambassador Bolton’s book is “nasty & untrue,” thus implicitly acknowledging that its contents had been at least partially described to him. He also said that the book was “All Classified National Security.”112

- On February 3, Vanity Fair reported that the President “has an enemies list,” that “Bolton is at the top of the list,” and that the “campaign against Bolton” included Ms. Knight’s January 23 letter asserting that the manuscript contained classified information.113 It also reported that the President “wants Bolton to be criminally investigated.”114

- On February 21, the Washington Post reported that “President Trump has directly weighed in on the White House [prepublication] review of a forthcoming book by his former national security adviser, telling his staff that he views John Bolton as ‘a traitor,’ that everything he uttered to the departed aide about national security is classified and that he will seek to block the book’s publication.”115 The President vowed: “[W]e’re going to try and block the publication of [his] book. After I leave office, he can do this.”116

- As described in detail above, Ambassador Bolton’s book went through a four-month prepublication-review process with the career professionals at NSC, during which he made innumerable revisions to the manuscript in response to Ms. Knight’s concerns. At the end of that exhaustive process, she stated that she had no further edits to the manuscript,117 thereby confirming, as the Government has admitted, that she had concluded that it did not contain any classified information.118

- At the conclusion of the prepublication-review process on April 27, Ms. Knight thought that Ambassador Bolton was entitled to receive the pro-forma letter clearing the book for publication and suggested that it might be ready that same afternoon.119 She and Ambassador Bolton even discussed how the letter should be transmitted to him.120

- During that same April 27 conversation, Ms. Knight described her “interaction” with unnamed others in the White House about the book as having “been very delicate,”121 and she had “some internal process considerations to work through.”

- After April 27, six weeks passed without a word from the White House about Ambassador Bolton’s manuscript, despite his requests for a status update.122

- When the White House finally had something new to say, it was to assert its current allegations of classified information on June 8, in a letter that—by the White House’s own admission—was prompted by press reports that the book was about to be published.123

- Even though the manuscript was submitted to NSC on December 30, 2019, and despite the exhaustive four-month review and the six weeks of silence that had passed since Ms. Knight’s approval of the manuscript on April 27, the White House’s June 8 letter gave itself until June 19—only four days before the book was due to be published—to provide Ambassador Bolton’s counsel with a redacted copy of the book identifying the passages the White House purported to believe were classified.

- On the eve of this lawsuit being filed, in response to a question about this lawsuit, the President stated: “I told that to the attorney general before; I will consider every conversation with me as president highly classified. So that would mean that if he wrote a book, and if the book gets out, he’s broken the law.”124 The President reiterated: “Any conversation with me is classified.”125 The President added that “a lot of people are very angry with [Bolton] for writing a book” and that he “hope[d]” that Ambassador Bolton “would have criminal problems” due to having published the book.126

- On June 16, the NSC provided to Ambassador Bolton a copy of the manuscript with wholesale redactions removing the portions it now claims are classified. Consistent with President Trump’s claim, statements made by the President have been redacted, as have numerous passages that depict the President in an unfavorable light.127

It is clear from this evidence that the White House has abused the prepublication-review and classification process, and has asserted fictional national security concerns as a pretext to censor, or at least to delay indefinitely, Ambassador Bolton’s right to speak.

While Goldsmith and Lederman focused, with good reason, on Ellis’ role, Bolton is focused on President Trump’s role. Bolton lays out abundant evidence that the reason this prepublication review went off the rails is because the President, knowing how unflattering it was to him, made sure it did.

And that raises entirely new issues because under a SCOTUS precedent called Navy v. Egan, the Executive has long held that the President has unreviewable authority over classification and declassification decisions. That doesn’t change contract law. And–given that the courts have already granted the President a limited authority to protect the kinds of things being called SCI here under Executive Privilege–it raises real questions about whether Trump is relying on the proper legal claim here (which may be a testament to the fact that Executive Privilege holds little sway over former government officials).

Still, courts have sanctioned a bunch of absurdity about classification under the Navy v. Egan precedent, arguably far beyond the scope of what that decision (which pertained to clearances) covered. Yet, I would argue that Bolton has made Navy v. Egan a central question (though he does not mention it once) in this litigation.

Can the President retroactively classify information as SCI solely to retaliate against someone for embarrassing him — including by exposing him to criminal prosecution under the Espionage Act? That’s the stuff of tyranny, and Royce Lamberth is not the judge who’ll play along with it.

Let me very clear however, particularly for the benefit of some frothy leftists who are claiming — in contradiction to all evidence — that liberals are somehow embracing Bolton by criticizing Trump’s actions here: Bolton’s plight is not that different from what whistleblowers claim happens to them when they embarrass the Executive Branch generally. Their books get held up in review and some of them get prosecuted under the Espionage Act.

What makes this more ironic, involving Bolton, is that he has been on the opposite side of this issue. Indeed, the Valerie Plame leak investigation focused closely on whether Dick Cheney’s orders to Scooter Libby to leak classified information — after which he leaked details consistent with knowing Plame’s covert status, as well as details from the National Intelligence Estimate — were properly approved by George Bush. Bolton was a party to that pushback and his deputy Fred Fleitz was suspected of having had a more active role in it. In that case, the President (or Vice President) retaliated for the release of embarrassing information by declassifying information for political purposes. But in that case, the details of what the President had done have remained secret, protected by Libby’s lies to this day.

In this case, Bolton can present a long list of evidence — including the President’s own statements — that suggest these classification decisions were retaliatory, part of a deliberate effort to trap Bolton in a legal morass.

So Bolton isn’t unique for his treatment as a “whistleblower” (setting aside his cowardice in waiting to say all this). He’s typical. What’s not typical is how clearly the President’s own role and abusive intent is laid out. And because of the latter fact — because, as usual, Trump hasn’t hidden his abusive purpose — it may more directly test the limits of the President’s supposedly unreviewable authority to classify information. So, ironically, someone like Bolton may finally be in a position to test whether Navy v. Egan really extends to sanctioning the retroactive classification of information solely to expose someone to criminal liability.