“Show Me the Metadata:” A Forensic Tie Between Shadow Brokers and Guccifer 2.0

On October 16, 2017, some of the last words the persona Shadow Brokers (TSB) ever wrote hailed my journalism.

TSB special shouts outs to Marcy “EmptyWheel” Wheeler, is being what true journalist and journalism is looking like thepeoples!

TheShadowBrokers, brokers of shadows.

As I noted at the time, I really didn’t need or appreciate the shout-out. I wrote a serious post analyzing that TSB post, but mostly I was trying to tell TSB to fuck off and leave me alone.

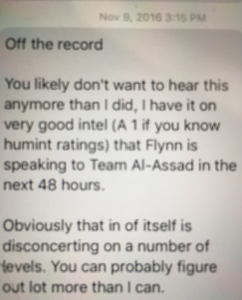

That was months after I told the FBI that I thought that someone I knew, whom I will refer by the pseudonym “Phil,” might be the voice of TSB, and less than a week after I got a Psycho-themed threat I deemed worthy of calling the cops.

As I laid out here, I told the FBI that months before Phil had left a comment on my site on July 28, 2016, signed [email protected], he had done some paranoid things starting on June 14, 2016, including making multiple references to ties he claimed to have with Russia. He then attended a Trump rally on August 13, 2016, taking pictures he would later suggest were really sensitive.

In addition to my suspicions about Guccifer 2.0, I also told the FBI that I suspected Phil was part of the operation that had been dumping NSA exploits and other records on the Internet starting in August 2016.

Unlike with Guccifer 2.0, Phil never signed a comment at the site under the name TSB — though on September 21, 2017, someone left a comment asking for my opinion about the ways the government was pursuing TSB.

‘Merican

Is what you say easier get FISA than Criminal warrant or FISA keep secret from rest of government, but Criminal warrant maybe not? FBI is not intelligence agency is law enforcement agency why have access FISA? You write many articles about the shadow brokers, what you think FISA or Criminal for the shadow brokers? You thinking anyone in US government is looking for the shadow brokers? US government not even say name “name that shall never be spoken”. What is best way discover national security letter sent to your service provider? …asking for a friend!

I thought Phil might be TSB, in part, because Phil had said almost identical things to me in private that TSB said publicly months later. There were other things in TSB’s writing that resonated with stuff I knew about Phil. And while Phil and I never (as far as I recall) talked about TSB, at least once he did say some other things that went a long way to convincing me he could be TSB; I thought he was seeking my approval for what TSB was doing, approval I was unwilling to give.

There are, however, public exchanges between the persona TSB and me, in addition to that shout out in what turned out to be TSB’s swan song.

For example, after I wrote a post on January 5, 2017 wondering why the government hadn’t included TSB in any of its discussions of election year hacking, TSB tweeted to me, complaining that I had described TSB as “bitching” about the coverage, rather than calling it “trolling.” (Note, the language in these screen caps reflects the language used by the people who first archived these tweets, so don’t go nuts about the Russian.)

TSB then RTed my article, suggesting other outlets were complicit for not asking the same questions.

The first tweet, at least, didn’t adopt the fake Borat voice that TSB used to mask a very fluent English, though I think there were some other tweets TSB sent that day where that may be true as well. In neither of these tweets did TSB mock me for misspelling “Whither” (the post’s title originally spelled it “Wither”); that’s a bit odd, because TSB rarely passed up any opportunity to be an asshole on Twitter.

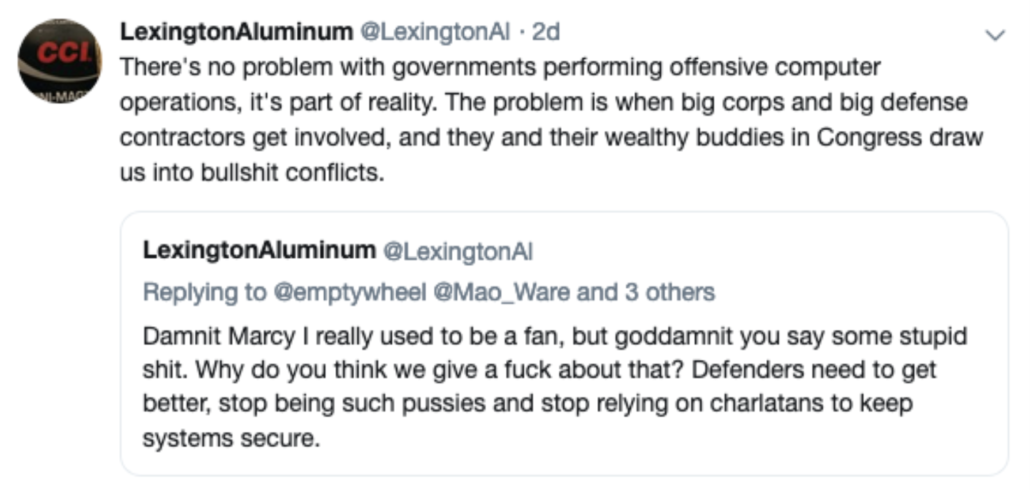

Then, on July 18, 2018, after I had revealed I had shared information with the FBI, someone started a Twitter account under the name LexingtonAl that ultimately claimed to be — and was largely viewed as, by those who followed it — TSB (the persona deleted most tweets in February 2019, but many are saved here). Starting in December 2018, Lex and I had several exchanges about what TSB had actually done.

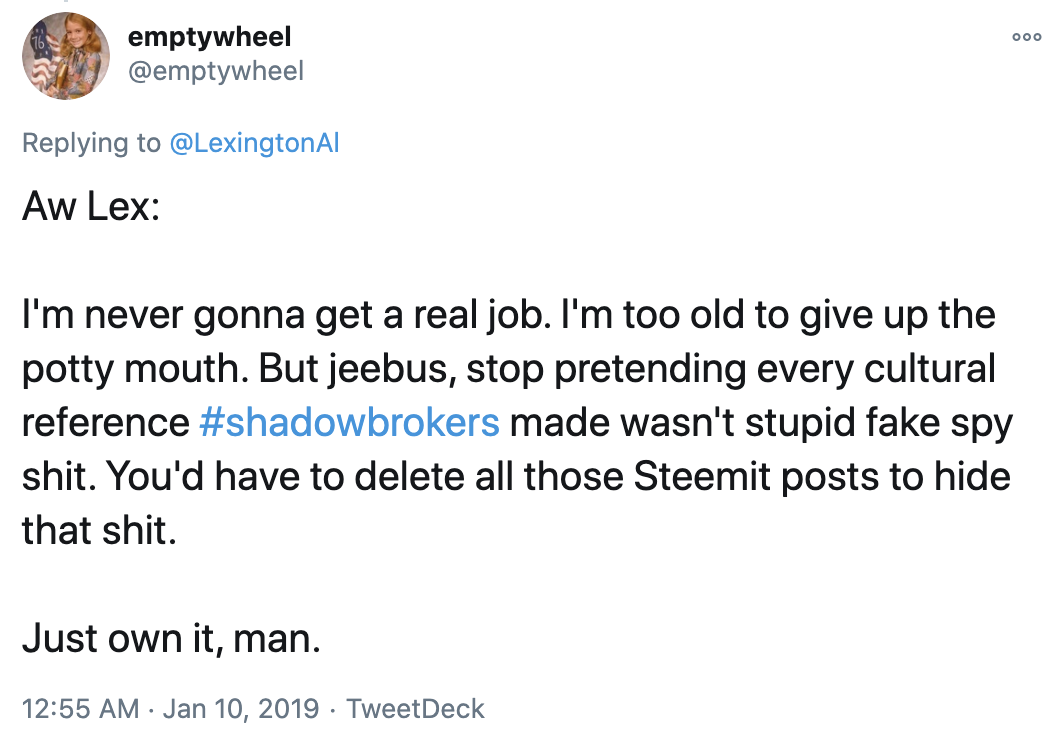

Here’s my side of one from that month where I pointed out a problem with Lex’s claim that TSB consisted of just three contractors who leaked the files to reveal US complicity with tech companies to other Americans. The claim didn’t accord with having sent the files to WikiLeaks (as both WikiLeaks and TSB claimed in real time).

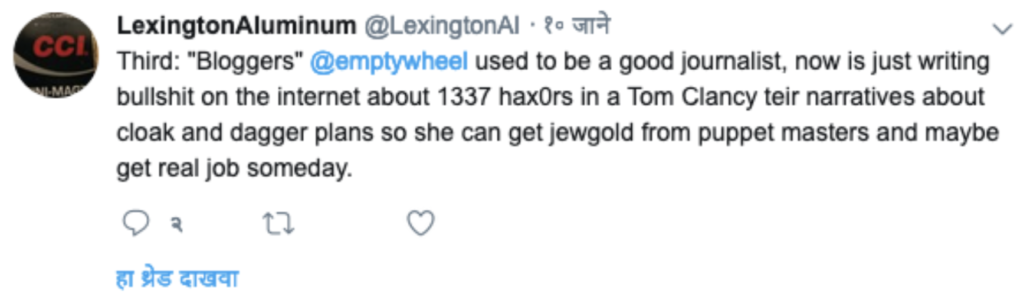

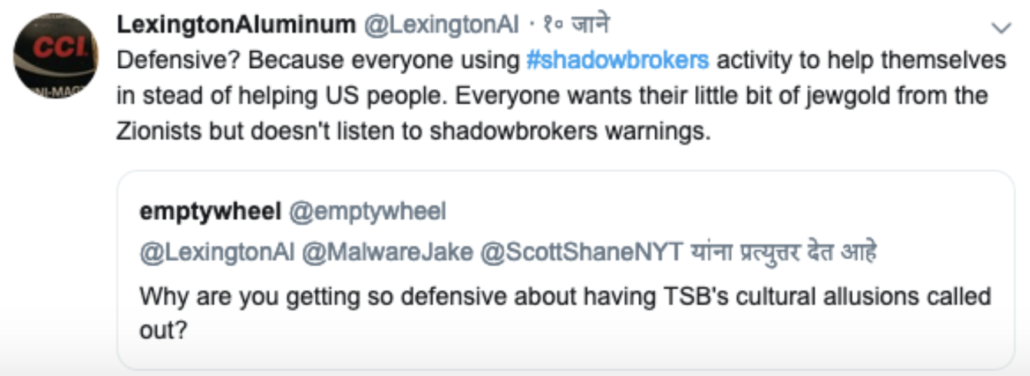

At the time, Lex went on an anti-Semitic rant about things he hated. Assuming that Lex is TSB (as he claimed), I got demoted from being TSB’s favorite journalist to third on the list of things Lex hated.

Note: when I interacted with Phil, he was never anti-Semitic (though he was a raging asshole when angry), but Lex was clearly even more disturbed than Phil was in the period when I interacted with him.

Then, in January, Lex bitched (again, in anti-Semitic terms) about a post I had done noting that, given Twitter’s poor security at the time, the Twitter DMs that Hal Martin allegedly sent Kaspersky might have served to frame him.

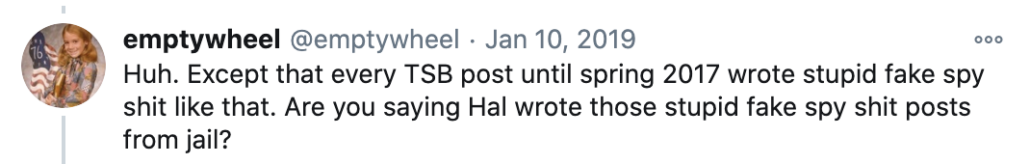

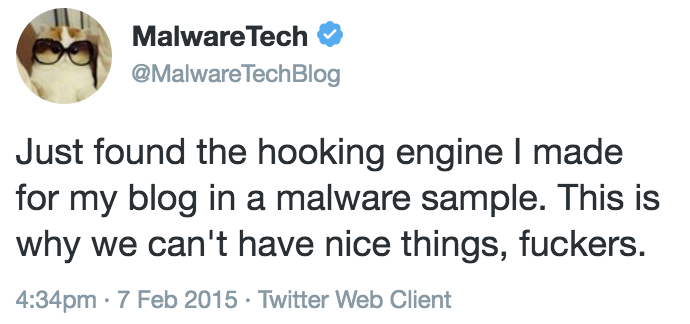

The post had noted that the early TSB posts — including a number sent after Martin was arrested — had relied on similar cultural allusions as the DMs sent from Martin’s Twitter account. Shortly thereafter the FBI arrested Martin in a guns-wagging raid on his home in Maryland. Per this Kim Zetter story, the Tweets had mentioned the 2016 version of Jason Bourne and Inception. I reiterated that on Twitter.

It was a factual observation supported by the content of the earlier TSB posts, not a comment about any spookiness behind the release of the files.

I asked why TSB was so defensive about having those cultural allusions called out.

Lex responded with another anti-Semitic rant.

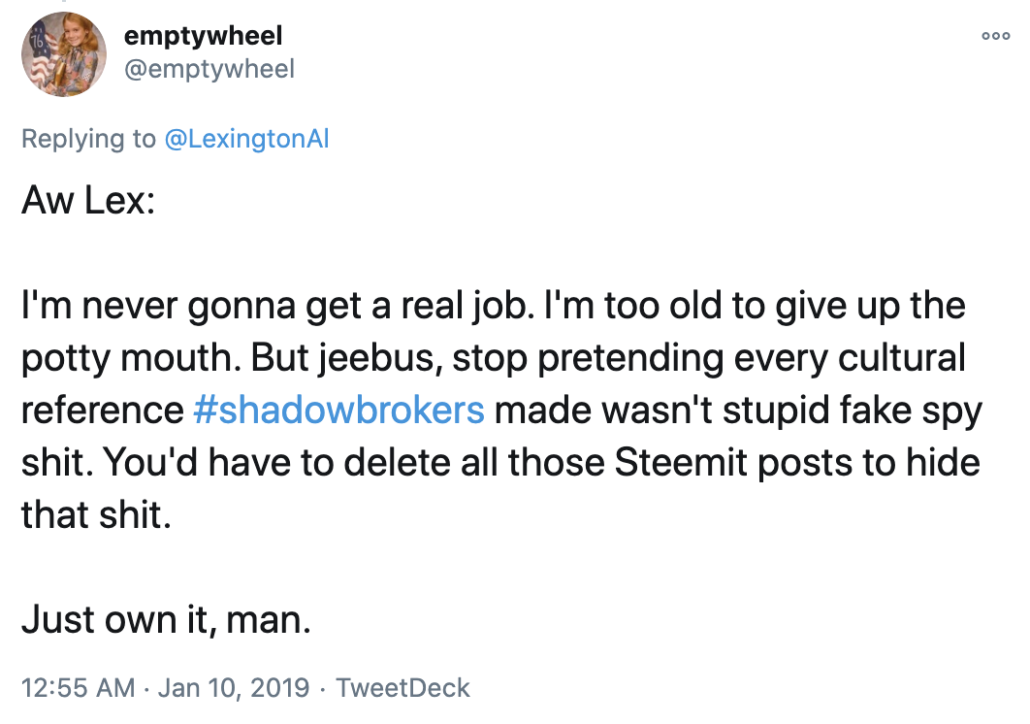

I responded,

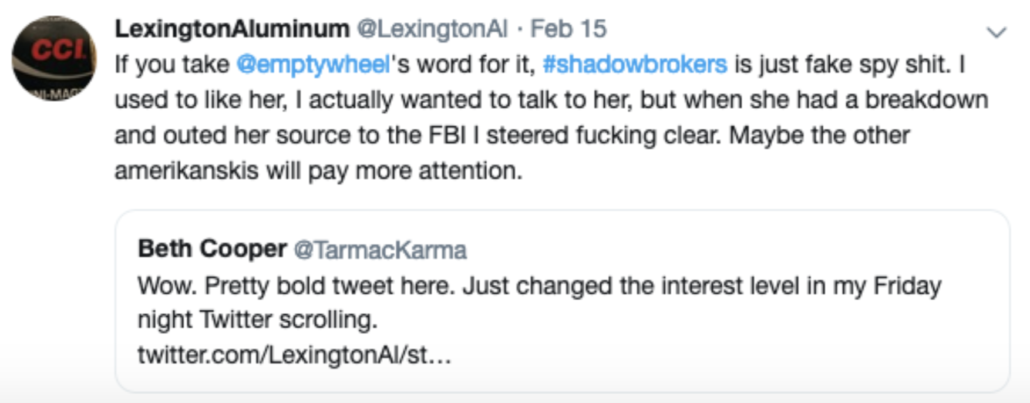

Finally, in February 2019, Lex invoked me — including that I had “had a breakdown and outed her source” — sort of out of the blue in the middle of what might be called his claimed doctrine behind the leaks.

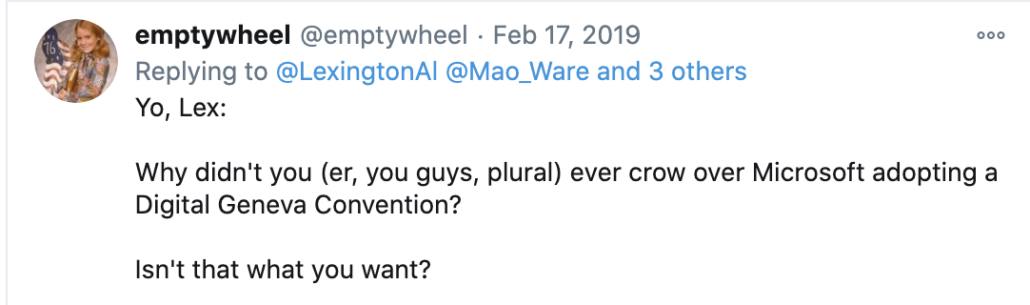

I noted that if his claimed doctrinal explanation were true, then TSB would have done a victory lap (and stopped dropping files) when Microsoft President Brad Smith started advocating for a Digital Geneva Convention in February 2017, which would have brought about an end to the practice that, Lex claimed, was his reason for dumping the files.

Not only didn’t TSB mention that in real time (instead choosing to exacerbate the tensions between the US and Microsoft), but TSB kept dropping files for six months after that.

Lex responded with another attack.

I have far less evidence that I could share to prove that TSB or Lex are Phil. But little noticed in the midst of TSB’s widely-discussed obsession with Jake Williams, a former NSA hacker whom TSB probably tried to frame as the source of the files, TSB also had an obsession with me — and certainly took notice when I revealed that I had gone to the FBI.

All that said, virtually all of these communications post-dated the time when I went to the FBI.

I went to the FBI in the wake of the WannaCry attack. The attack, reportedly a North Korean effort to make use of the tools dropped by TSB that went haywire, ended up causing a global worm attack that shut down hospitals and caused hundreds of billions of dollars in damage. When I have alluded to the ongoing damage I was trying to prevent, that’s what I mean: the indiscriminate release of NSA exploits to the public which, in that case, literally shut down hospitals on the other side of the world.

There’s no defense for that.

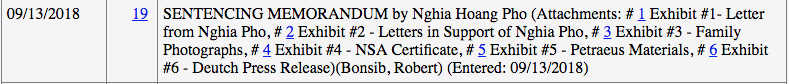

While I had been trying to find some way to share my concerns long before that, I may never have met directly with the FBI about any of my suspicions except for another detail: I learned that there was a forensic tie between the Guccifer 2.0 and TSB personas. While, at the time, I had moderate confidence about both my belief that Phil had a role in the Guccifer operation and moderate confidence that he was TSB, when I learned there was a forensic tie between the two of them, it increased my confidence in both.

A strong caveat is in order: the forensic tie isn’t decisive; it could be insignificant, or untrue.

The forensic tie is that someone logged into one of the Guccifer 2.0 accounts — I think the WordPress account — using the same IP address as someone who logged into the early staging sites — either Pastebin or GitHub — for the TSB operation.

If someone using the same IP address accessed both sites — probably using a VPN — it could mean either that the same person was involved, or whoever staged these things was doing little to cover their tracks and outsiders were accessing their infrastructure. One of the people who told me about this forensic tie interpreted it as a deliberate attempt to tie the two operations together, sort of yanking the government’s chain.

I learned of this forensic tie from multiple people, all of whom are credible. That said, I can’t rule out that they learned it from the same person. No one has reported on this in the years since these operations, even though I’ve tried to get better sourced journalists to go chase it down. Indeed, I recently learned that a top outside expert on issues related to TSB did not know this forensic detail.

The FBI had to chase down a lot of weird forensic shit pertaining to these influence operations, because that’s how this kind of operation works. I have noted in the past, for example, that some script kiddies tried to hijack an early Guccifer 2.0 email account; that was investigated by a Philadelphia grand jury in spring of 2017. So this forensic tidbit could be similarly unrelated to the people behind the operation.

So I don’t want to oversell this forensic tie. I do want to encourage others to try to chase it down.

But it was something that significantly influenced my understanding of all this in 2017, when files released by TSB had just caused the worst damage of any cyber attack in history, to date.

When I mentioned the forensic tie during my FBI interview, the lead agent responded that they couldn’t confirm or deny anything during the interview. I wasn’t there to get confirmation.

Still, if it’s true — given what we’ve learned since about the Guccifer 2.0 operation — it is hugely significant.

TSB started staging its release — per this really helpful SwitHak timeline — on July 25, the same day Trump directed people to get Roger Stone to chase down the next WikiLeaks releases. The first files were encrypted on August 1, after Stone had already pitched Paul Manafort on a way to “save Trump’s ass.” TSB loaded the NSA files on GitHub just after Stone published a piece suggesting that Guccifer 2.0, and not Russia, had hacked the DNC. TSB went live overnight on August 12-13, not long after Guccifer 2.0 publicly tweeted to Stone, “Thanks that u believe in the real #Guccifer2.” WikiLeaks publicized the effort on August 15, after some private back and forth between Guccifer 2.0 and Stone, including Guccifer 2.0’s question, “thank u for writing back . . . do u find anyt[h]ing interesting in the docs i posted?” And, per the SSCI analysis and my own, WikiLeaks helped to boost TSB the same day Jerome Corsi may have started giving Roger Stone advance information about the content of the John Podesta emails that wouldn’t be dropped for another two months (SSCI appears not to have considered, much less concluded, that Guccifer 2.0 might be Stone’s source).

If the forensic tie between Guccifer 2.0 and TSB is real, it means that during precisely the same period when Roger Stone was desperately trying to optimize the release of the John Podesta files to save his buddies Paul Manafort and Donald Trump, related actor TSB was beginning a year-long effort to burn the NSA to the ground.