Out of curiosity and a good deal of masochism, I listened to the latest podcast of “The Corner,” the frothy right wingers who spend their time spinning conspiracy theories about the Durham investigation.

It was painful.

At every step, these men simply assert evidence must exist — like a Democratic order to bring dirt to the FBI — for which there’s no evidence. They ignore really basic facts, such as that Sussmann was necessarily working with the FBI because his client was being systematically hacked, and therefore it wasn’t just Christopher Steele who had ongoing ties to the Bureau. They make a huge deal about the fact that the US government’s Russian experts know each other, and that Christopher Steele persistently reported on topics — like Rosneft — that really were and are important to British and US national security and on which he had legitimate expertise.

They’re already starting to make excuses for Durham (such as that Durham chose not to obtain privileged emails the same way Mueller and SDNY did, without noting that Mueller had probable cause of a crime, which Durham admits he does not, much less that Mueller got them in a different way and a different time then they believe he did).

They keep making much of the coincidence of key dates in 2016 — “We continue to have a very, very tight timeline that that accelerates” — but never mention either the WikiLeaks dump of the DNC emails or Trump’s request that Russia hack Hillary some more, a request that was followed closely by a new wave of attacks. Those two events in July 2016 explain most of the actions Democrats took in that period, and these men don’t even exhibit awareness (or perhaps the belief?) that the events happened.

Worse still, they are ignorant of, or misrepresent, key details.

For example, all but Hans Mahncke assert that John Brennan must have been acting on some kind of corrupt intelligence in July 2016, rather than real intelligence collected from real Russian sources. They do so even though Billy Barr described in his book bitching at Trump after Trump complained that Durham found that, “the CIA stayed in its lane in the run-up to the [2016] election.”

Emblematic of the fraying relationship between the President and me was a sharp exchange at the end of the summer in the Oval Office. To give the President credit, he never asked about the substance of the investigation but just asked pointedly when there might be some sign of progress. On this occasion, we had met on something else, but at the end he complained that the investigation had been dragging on a long time. I explained that Durham did not get the Horowitz report until the end of 2019, and up till then had been look- ing at questions, like any possible CIA role, that had to be run down but did not pan out.

“What do you mean, they didn’t pan out?” the President snapped.

“As far as we can tell, the CIA stayed in its lane in the run-up to the election,” I said.

The President bristled. “You buy that bullshit, Bill?” he snarled. “Everyone knows Brennan was right in the middle of this.”

I lost it and answered in a sarcastic tone. “Well, if you know what happened, Mr. President, I am all ears. Maybe we are wasting time do- ing an investigation. Maybe all the armchair quarterbacks telling you they have all the evidence can come in and enlighten us.”

Durham looked for this evidence for years. It’s not there (and therefore the intelligence Brennan viewed is something other than the dossier or even the Russian intelligence product that the frothers also spin conspiracies on).

All but Fool Nelson misrepresent a July 26, 2016 email from Peter Fritsch to WSJ reporter Jay Solomon, which says, “call adam schiff, or difi for that matter. i bet they are concerned about what page was doing other than giving a speech over 3 days in moscow,” suggesting that that must be proof the top Democrats on the Intelligence Committees had the Steele dossier, rather than proof that it was a concern to see an advisor to a Presidential campaign traveling to Russian and saying the things Page was saying. (Jeff Carlson makes the same complaint about former Ambassador to Russia Michael McFaul’s observations about something that all experienced Russia watchers believed was alarming in real time.)

They get the evidence against Carter Page wrong, among other ways by misstating that all his time in Moscow had been accounted for and that the rumor he met with Igor Sechin was ever entirely debunked. “Of course it’s impossible. He was chaperoned. He had a hotel. He had a driver. Without people noticing.” For example, the son of the guy who brought Page to Russia, Yuval Weber, told the FBI that they weren’t with Page 100% of the time and there was a rumor that he had met with Sechin.

In July, when Page had traveled to give the commencement speech at NES, Weber recalled that it was rumored in Moscow that Page met with Igor Sechin. Weber said that Moscow is filled with gossip and people in Moscow were interested in Page being there. It was known that a campaign official was there.

Page may have briefly met with Arkady Dvorkovich at the commencement speech, considering Dvorkovich was on the board at NES. But Weber was not aware of any special meeting.

[redacted] was not with Page 100% of the time, he met him for dinner, attended the first public presentation, but missed the commencement speech. They had a few other interactions. Page was very busy on this trip.

This testimony was consistent with Mueller’s conclusion about Page’s trip: given boasts he made to the campaign, “Page’s activities in Russia — as described in his emails with the Campaign — were not fully explained.”

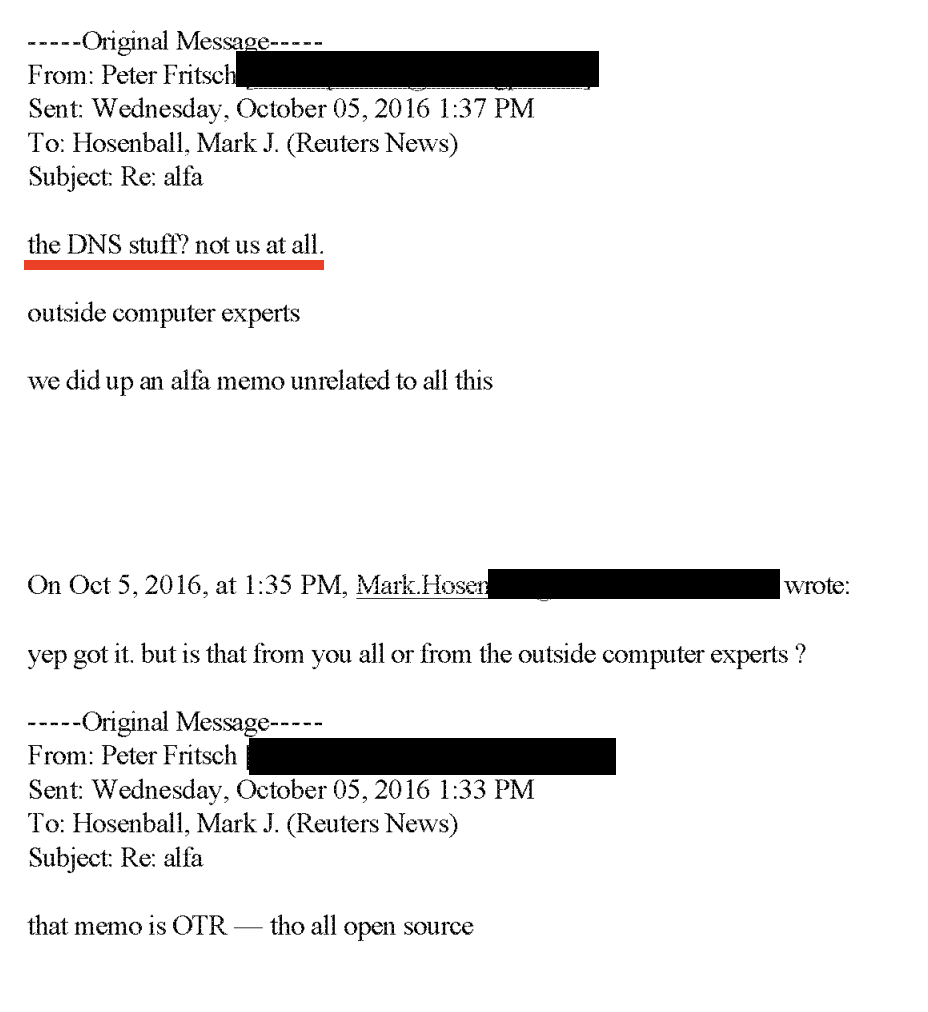

They badly misrepresent emails between a handful of journalists and Fusion GPS, spinning real skepticism exhibited by journalists as journalists somehow conspiring with Fusion. Indeed, they repeatedly point to an email from WaPo’s Tom Hamburger pushing back on the Sechin claim, “That Page met with Sechin or Ivanov. ‘Its bullshit. Impossible,’ said one of our Moscow sources.” They claim that Hamburger nevertheless reported the story after that. They’re probably thinking of this story, which reported Page’s 2014 pro-Sechin comments, not that he had met with the man in 2016.

After the Obama administration added Rosneft Chairman Igor Sechin to its sanctions list in 2014, limiting Sechin’s ability to travel to the United States or do business with U.S. firms, Page praised the former deputy prime minister, considered one of Putin’s closest allies over the past 25 years. “Sechin has done more to advance U.S.-Russian relations than any individual in or out of government from either side of the Atlantic over the past decade,” Page wrote.

In other words, they’re claiming journalists doing actual journalism and not reporting what Fusion fed them is somehow corrupt, when it is instead an example, among many, of failed attempts by Fusion to get journalists to run with their tips.

They complain that Fusion was pointing journalists to Felix Sater, in spite of the fact that Sater really was central to tying Trump Organization to Russian funding and really did pitch an impossibly lucrative real estate deal in the year before the campaign that involved secret communications with the Kremlin and sanctioned banks and a former GRU officer, a deal that Michael Cohen and Trump affirmatively lied to cover up for years.

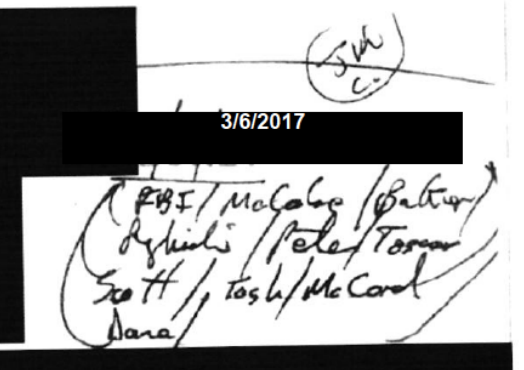

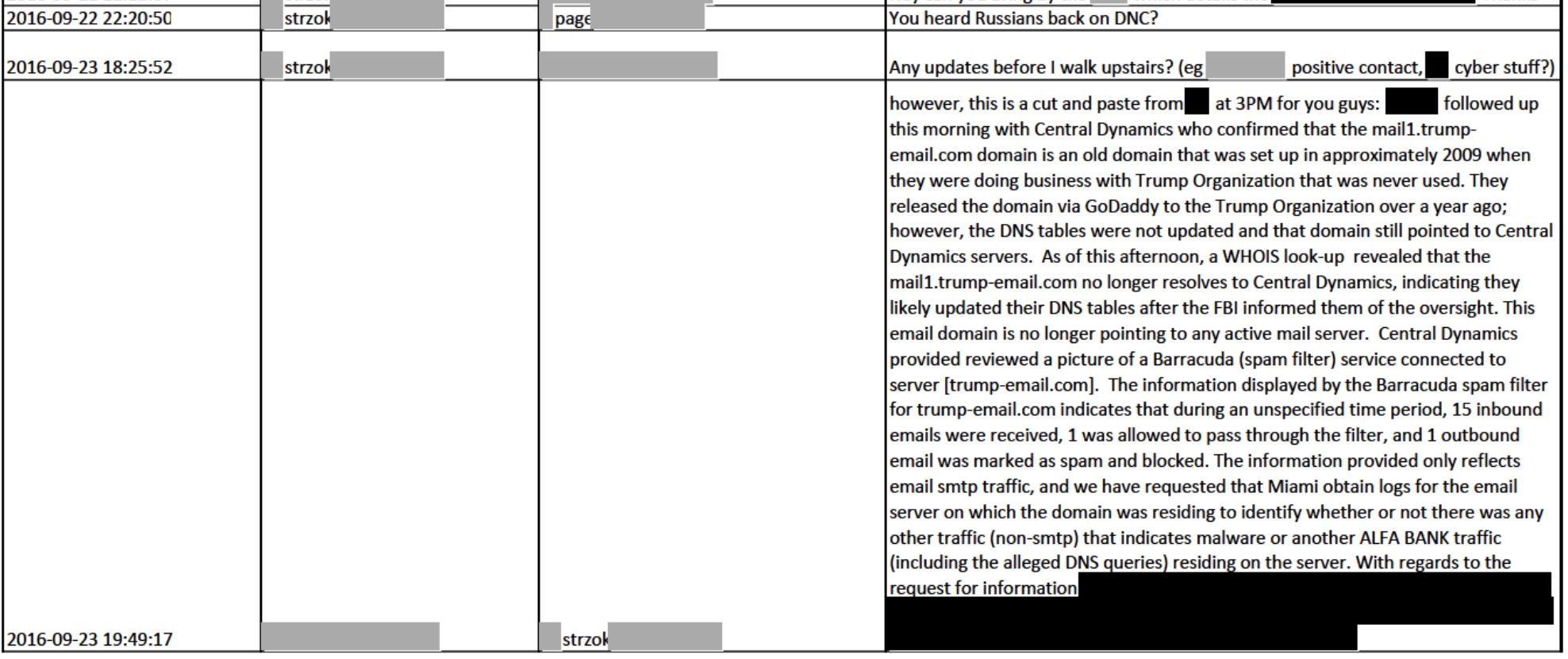

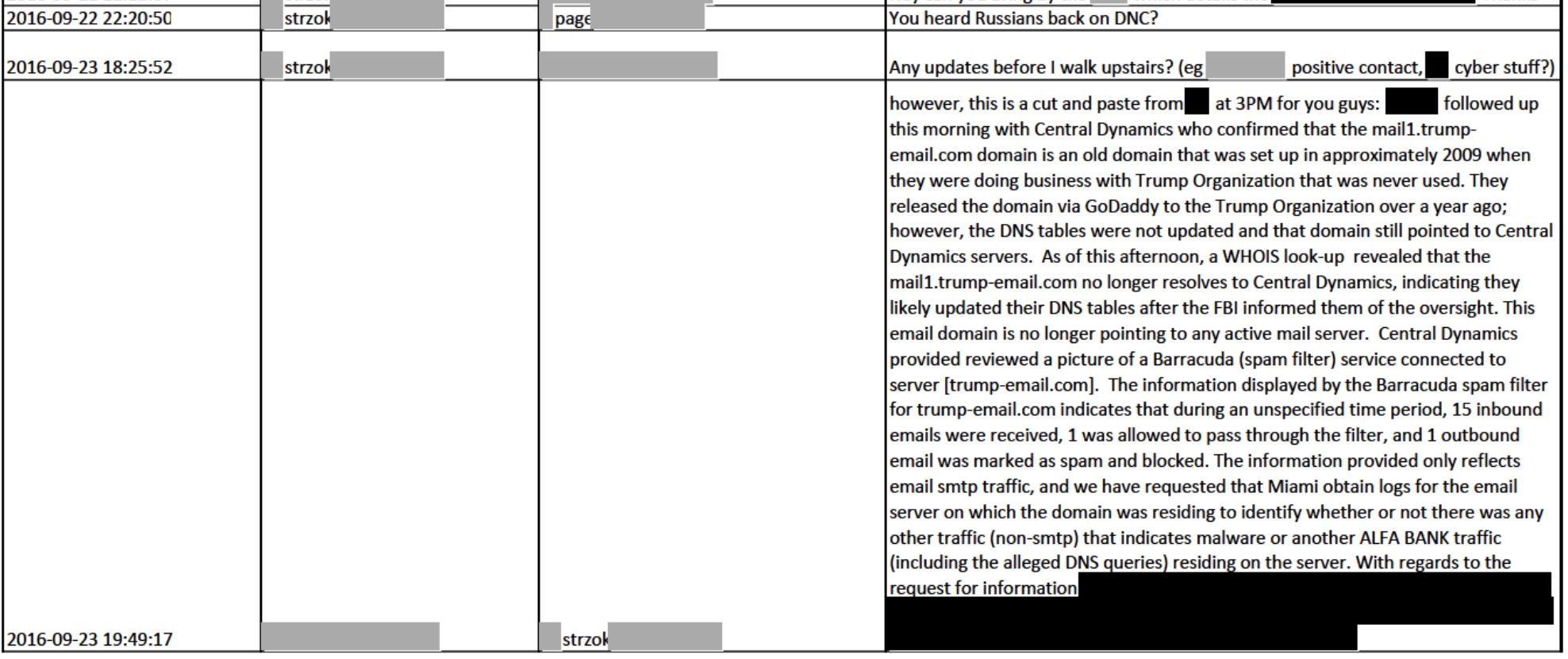

They grossly misrepresent a long text to Peter Strzok reflecting someone else’s early inquiries on the DNS allegation to Cendyn, imagining (the redaction notwithstanding) that it reflects the FBI concluding already at that point that there was nothing to the DNS allegations and not that the FBI inquiry instead explains why Trump changed its own DNS records shortly thereafter (addressing one but not both of the questions raised by NYT reporting).

Obviously, none of them seem interested in the nearly-contemporaneous text from Strzok noting that “Russians back on DNC,” presumably reflecting knowledge of the serial Russian effort to steal Hillary’s analytics stored on an AWS server, a hack that — because it involved an AWS server, not a DNC-owned one — not only defies all the favorite right wing claims about what went into the Russian attribution, but also explains why Sussmann would be so concerned about seeming evidence of ongoing covert communication between Trump and a Russian bank. The Russians kept hacking, both in response to Trump’s request in July, and in the days before and after Sussmann met with James Baker in September.

Crazier still, none of these men seem to have any understanding of two details of the back-and-forth between Sussmann, the FBI, and NYT, one that is utterly central to the case against Sussmann. They conflate a request FBI made to NYT days after Sussmann’s meeting with the FBI to kill the story — one made with the assent of Sussmann and Rodney Joffe — with later follow-up reporting by the NYT reporting that the FBI had not substantiated the DNS allegation. Those were at least two separate calls! Durham had chased down none of them before he indicted Sussmann. It wasn’t until almost six months after charging Sussmann that Durham corroborated Sussmann’s HPSCI testimony that Sussmann and Joffe agreed to help kill the initial NYT story, which provides a lot of weight to Sussmann’s explanation for his meeting with James Baker, that he wanted to give the FBI an opportunity to investigate the allegation before the press reported on it. As a result, Mahncke states as fact that Sussmann’s September 18 text telling Baker, “I’m coming on my own – not on behalf of a client or company – want to help the Bureau,” (even ignoring the temporal problem it creates for Durham’s charge) proves Sussmann lied, when in fact, his and Joffe’s efforts to help the Bureau kill the story strongly supports Sussmann’s public story.

If you don’t know that Sussmann and Joffe helped the FBI to kill what would have been a damning story about Trump, you’re not assessing the actual evidence against Sussmann as opposed to Durham’s conspiracy theories.

All that said, laying out all the ways the supposed experts on the frothy right prove they’re unfamiliar with the most basic details about events in 2016 and since is not why I wrote this post.

I wrote this post because of the way Fool attempted to explain away the inconvenience of Paul Manafort to his narrative. Fool went on at length showing how (a possible Russian fabrication claiming) Hillary’s plan to focus on Trump’s ties to Russia must have predicated an investigation that started before that point. He ignored, entirely, that an FBI investigation had already been opened on Page by then (and all four frothers ignore that Fusion started focusing on Page when Paul Singer was footing the bill). But Fool does acknowledge that the money laundering investigation into Manafort had already been opened before Crossfire Hurricane started. He treats Manafort’s very real corrupt ties to Putin-backed oligarchs as a lucky break for what he imagines to be Hillary’s concocted claims, and not a fact that Trump ignored when he hired the man to work for him “for free.” “Luckily, I don’t know if this was a coincidence or not, Manafort joined the Trump campaign and that gave them a reason to look deeper.” In other words, Fool suggests Manafort’s hiring might be part of Hillary’s devious plot, and not the devious plot of Oleg Deripaska to get an entrée to Trump’s campaign or the devious alleged plot of Mohammed bin Zayed to direct Trump policy through Tom Barrack.

Because I expect the circumstances of Manafort’s hiring may become newsworthy again in the near future and because Deripaska was pushing an FBI investigation into Manafort before Hillary was, I wanted to correct this detail.

According to Gates, the effort to install Manafort as campaign manager started earlier than most people realize, in January 2016, not March.

In January 2016, Gates was working mostly on [redacted] film project. Gates was also doing some work on films with [redacted] looking for new DMP clients, and helping Manafort pull material together to pitch Donald Trump on becoming campaign manager. Roger Stone and Tom Barrack were acting as liaisons between Manafort and Trump in an effort to get Manafort hired by the campaign. Barrack had a good relationship with Ivanka Trump.

Tom Barrack described to Mueller how Manafort asked for his help getting hired on Trump’s campaign in that same month, January 2016.

But Manafort may have started on this plan even before January 2016. Sam Patten told SSCI Kilimnik knew of the plan in advance. Patten’s explanation of his involvement in the Mueller investigation describes Ukrainian Oligarch Serhiy Lyovochkin asking him about it in late 2015.

In late 2015, Lyovochkin asked me whether it was true that Trump was going to hire Manafort to run his campaign. Just as I told Pinchuk that Putin’s perception of America’s capabilities was ridiculous, I told Lyovochkin that was an absurd notion; that Trump would have to be nuts to do such a thing.

In any case, even before his hiring was public, on March 20, Manafort wrote his Ukrainian and Russian backers to let them know he had installed himself with the Trump campaign. He sent one of those letters to Oleg Deripaska, purportedly as a way to get the lawsuit Deripaska had filed against Manafort dropped.

Gates was shown an email between Gates and Kilimnik dated March 20, 2016 and four letters which were attached to this email. Gates stated he was the person who drafted the letters on Manafort’s behalf. Manafort reviewed and approved the letters.

Manafort wanted Gates to draft letters announcing he had joined the Trump Campaign. Manafort thought the letters would help DMP get paid by OB and possibly help confirm that Deripaska had dropped his lawsuit against Manafort. Manafort wanted Kilimnik to let Deripaska know he had been hired by Trump and he needed to make sure there were not lawsuits against him.

Gates was asked why Manafort could not have employed counsel to find out of the Deripaska lawsuit had been dropped. Gates stated Manafort wanted to send Deripaska a personal note and to get a direct answer from Deripaska. Gates also thought this letter was a bit of “bravado on Manafort’s part.”

Gates was asked if the purpose of the letter to Deripaska was to determine if the lawsuit had been dropped, why didn’t the letter mention the lawsuit. Gates stated that Manafort did not want to put anything about the lawsuit in writing.

This explanation, true or not (and it’s pretty clear the FBI didn’t believe it), is critical to the frothers because even before Christopher Steele started collecting information on Trump, he was collecting information on Manafort at the behest of Deripaska in conjunction with this lawsuit. And Steele was feeding DOJ tips about Deripaska’s lawsuit before he started feeding the FBI dirt paid for by Hillary’s campaign. The first meeting at which Steele shared dossier information with Bruce Ohr, for example, Steele also pushed the Deripaska lawsuit, and not for the first time.

Either the Deripaska lawsuit was a cover story Manafort used consistently for years (including through his “cooperation” with Mueller in 2018), or it was real. Whichever it was, it bespeaks some kind of involvement by Deripaska long before Hillary got involved. Viewed from that perspective, the dossier (and Deripaska’s presumed success at filling it with disinformation) was just part of a brutal double game that Deripaska was playing with Manafort, one that led Manafort to share campaign strategy and participate in carving up Ukraine, another event the frothers are trying to blame on the ever-devious Hillary. Whichever it is, the process by which a bunch of Putin allies in Ukraine knew Trump was going to hire Manafort before Trump did is a big part of the story.

But according to the frothers, Hillary Clinton is just that devious that she orchestrated all of this.