Yesterday, the two sides in the Josh Schulte case presented their closing arguments.

It is always difficult to read how a jury will view a case, and in this case (in part for reasons I’ll lay out below) that’s all the more true. I could imagine any of a range of outcomes: full acquittal, acquittal on some charges, guilty on most but not all charges, or another hung jury (though I think it likely he’ll win acquittal on at least one or two charges).

This is what the jury will be deliberating about. The short version: Judge Furman seems very skeptical of the obstruction charge against Schulte, quite persuaded by the government’s CFAA charges, but very impressed by Schulte’s closing argument.

The charges

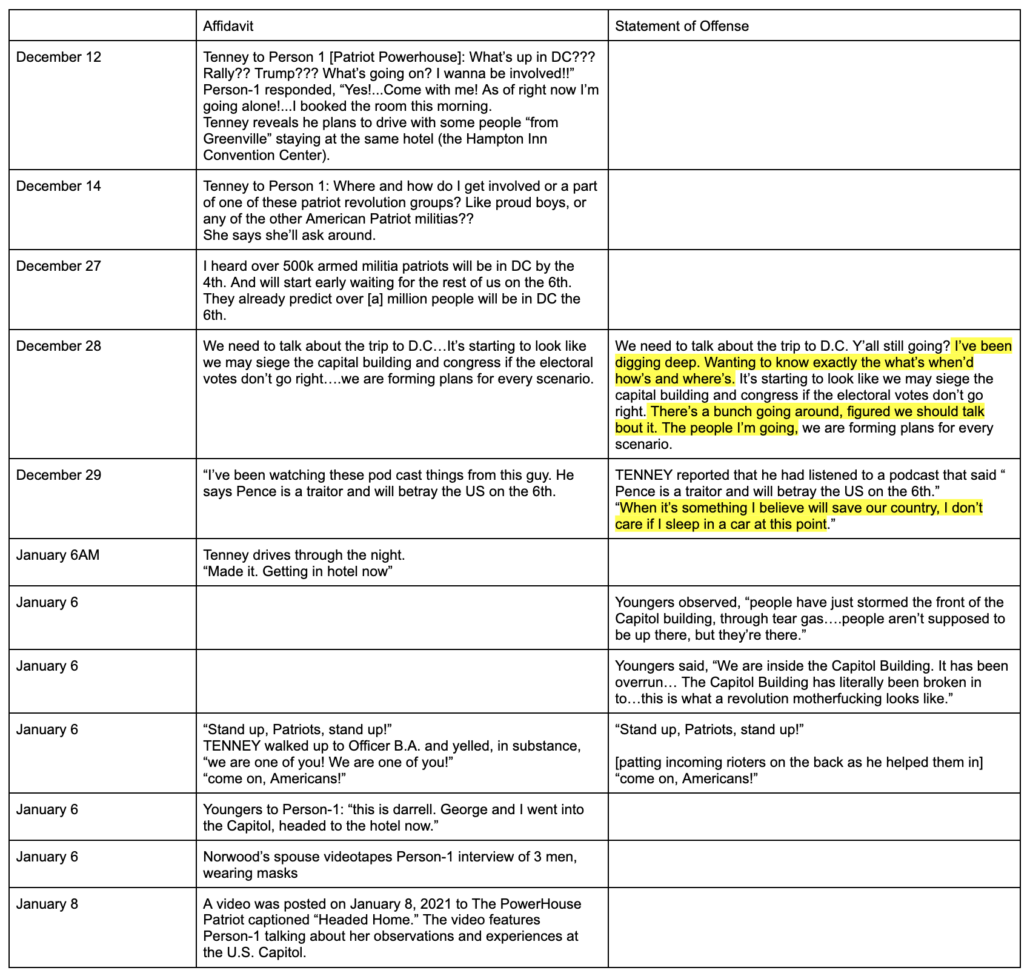

After his first mistrial, DOJ obtained a superseding indictment designed to break his alleged crimes into explicitly identifiable crimes, presumably to prevent the jury from getting confused about what specific actions allegedly constitute a crime, as the first jury appears to have done.

The indictment is generally broken into Espionage tied to files taken directly from the CIA’s servers (Counts One and Two), Espionage tied to stuff Schulte allegedly tried to send out from jail (Counts Three and Four), CFAA for hacking the CIA servers (Counts Five through Eight), and obstruction (Count Nine). I’ve put the legal code below, but here’s how Judge Furman described the charges in his draft jury instructions.

Specifically, Count One charges the defendant with illegal gathering of national defense information or “NDI.” Specifically, it charges that, on or about April 20, 2016, the defendant, without authorization, copied backup files of certain electronic databases (what I will refer to as the “Backup Files”) housed on a classified computer system maintained by the CIA (namely “DEVLAN”).

Count Two charges the defendant with illegal transmission of unlawfully possessed documents, writings, or notes containing NDI. Specifically, it charges that, between April and May 2016, the defendant, without authorization, retained copies of the Backup Files and communicated them to a third party not authorized to receive them, the organization WikiLeaks.

Count Five charges the defendant with unauthorized access to a computer to obtain classified information. Specifically, it charges that, between April 18 and April 20, 2016, the defendant accessed a 16 computer without authorization and exceeded his authorized access to obtain the Backup Files and subsequently transmitted them to WikiLeaks without authorization.

Count Six charges the defendant with unauthorized access to a computer to obtain information form a department or agency of the United States. Specifically, it charges that, on or about April 20, 2016, the defendant, accessed a computer without authorization or in excess of his authorized access, and copied the Backup Files.

Count Seven charges the defendant with causing transmission of a harmful computer command. Specifically, it charges that, on or about April 20, 2016, the defendant transmitted commands on DEVLAN to manipulate the state of the Confluence virtual server on DEVLAN.

Count Eight charges the defendant with causing transmission of a harmful computer command. Specifically, it charges that, on or about April 20, 2016, the defendant transmitted commands on DEVLAN to delete log files of activity on DEVLAN.

Counts Three and Four charge the defendant with crimes relating to the unlawful disclosure or attempted disclosure of NDI while he was in the Metropolitan Correctional Center (“MCC”), the federal jail.

Count Three charges that, in or about September 2018, the defendant had unauthorized possession of documents, writings, or notes containing NDI related to the internal computer networks of the CIA, and willfully transmitted them to a third party not authorized to receive them.

Count Four charges that, between July and September 2018, the defendant had unauthorized possession of documents, writings, and notes containing NDI related to tradecraft techniques, operations, and intelligence gathering tools used by the CIA, and attempted to transmit them to a third party or parties not authorized to receive them.

Finally, Count Nine charges the defendant with obstruction of justice. Specifically, it charges that between March and June 2017, the defendant made certain false statements to agents of the FBI during their investigation of the WikiLeaks leak.

Here’s that language with the legal statutes included:

Count One, 18 USC 793(d) and 2 (WikiLeaks Espionage), Illegal gathering of National Defense Information: For copying the DevLAN backup files on or about April 20, 2016.

Count Two, 18 USC 793(e) and 2 (WikiLeaks Espionage), Illegal transmission of unlawfully possessed NDI: For transmitting the backup files to WikiLeaks in or about April and May 2016.

Count Three, 18 USC 793(e) and 2 (MCC Espionage), Illegal transmission of unlawfully possessed NDI: For sending this information about DevLAN to Shane Harris in or about September 2018.

In reality, two groups — EDG and COG and at least 400 people had access. They don’t include COG who was connected to our DEVLAN through HICOC, an intermediary network that connected both COG and EDG. . . . There is absolutely NO reason they shouldn’t have known this connection exists. Step one is narrowing down the possible suspects and to completely disregard an ENTIRE GROUP and HALF the suspects is reckless. All they needed to do was talk to ONE person on Infrastructure branch or through ANY technical description / diagram of the network.”

Count Four, 18 USC 793(e) and 2 (MCC Espionage), Attempted illegal transmission of unlawfully possessed NDI: For staging a tweet and preparing to send out information about CIA’s hacking tools from at least July 2018 through October 2018. (Here’s the version of Exhibit 809 used at the first trial.)

Government Exhibit 801, page 3: “Which brings me to my next point — Do you know what my speciality was at the CIA? Do you know what I did for fun? Data hiding and crypto. I designed and wrote software to conceal data in a custom-designed file system contained with the drive slackspace or hidden partitions. I disguised data. I split data across files and file systems to conceal the crypto—analysis tools could NEVER detect random or pseudo-random data indicative of potential crypto. I designed and wrote my own crypto—how better to foll bafoons [sic] like forensic examiners ad the FBI than to have custom software that doesn’t fit into their 2-week class where they become forensic ‘experts.’”

Government Exhibit 809, page 8: “[tool from vendor report] — Bartender for [redacted] [vendor].”

Government Exhibit 809, page 10: “Additionally, [Tool described in vendor report] is in fact Bartender. A CIA toolset for [operators] to configure for [redacted] deployment.”

Government Exhibit 809, page 11: “[@vendor] discussed [tool] in 2016, which is really the CIA’s Bartender tool suite. Bartender was written to [redacted] deploy against various targets. The source code is available in the Vault 7 release.”

Count Five, 18 USC 1030(a)(1) and 2 (CFAA), Unauthorized access to a computer to obtain classified information: For hacking into the DevLAN backup files.

Count Six, 18 USC 1030(a)(2)(B) and 2 (CFAA), Unauthorized access of a computer to obtain classified information from a department or agency, for hacking into and copying the backup files.

Count Seven, 18 USC 1030(a)(5)(A) and 2 (CFAA), Causing transmission of harmful computer code: For the reversion of Confluence on April 20, 2016.

Count Eight, 18 USC 1030(a)(5)(A) and 2 (CFAA), Causing transmission of harmful computer code: For deleting log files on DevLAN on April 20, 2016.

Count Nine, 18 USC 1503, obstruction: For lying about having taken the backup files, keeping a copy of the letter he sent to the CIA IG, having classified information in his apartment, taking information from the CIA and transferring it to an unclassified network, making DevLAN vulnerable to theft, housing information from the CIA on his home computer, and removing classified information from the CIA.

The law

Based on orders Judge Jesse Furman issued and his response to Schulte’s Rule 29 motions for an acquittal after trial, it seems he views some of the charges to be stronger than others.

Espionage, WikiLeaks charges: Furman didn’t say much about the charges tied to Schulte allegedly obtaining and sharing the Vault 7 and 8 content with WikiLeaks. The transmission charge is the one that is most circumstantial (because the government made no claims about how Schulte got the stolen files out of the CIA and didn’t fully commit to how Schulte sent them to WikiLeaks), and so is one a jury might unsurprisingly find reasonable doubt on.

Espionage, MCC charges: There are two weaknesses to the MCC charges. First, Furman allowed Schulte to argue that because the Bartender information was already made public by WikiLeaks — a topic on which Schulte elicited helpful testimony — it was no longer National Defense Information (there’s more discussion on this issue here). There’s some question whether the Hickock information was NDI as well. But also, in the Bartender case, there’s a question about whether drafting a Tweet in a notebook is a significant enough step to be found guilty.

Obstruction: Furman seems quite skeptical the government has proven their case on obstruction and came close to ruling for Schulte on his Rule 29 motion on it. He ordered the two sides to brief whether the government had provided sufficient evidence of this charge. And in the conference on the instructions, he challenged whether things Schulte said on March 15, 2017 before receiving a grand jury subpoena could be included in an obstruction charge. As Schulte pointed out, too, his false statements from later interviews got less focus in this trial.

CFAA: Furman did rule against Schulte’s Rule 29 motions on the CFAA charges, suggesting he finds the evidence here much stronger. Schulte as much as admitted he had taken the steps DOJ claims he did to revert the confluence files, effectively admitting to one of the charges as written (and that’s what the government focused on in their rebuttal). That said, if he were found guilty on the CFAA charges, Schulte would mount an interesting appeal under SCOTUS’ Van Buren ruling, issued since his last trial, which held that you can’t be guilty of CFAA if you had authorized access. Schulte laid the groundwork to argue that while he didn’t have access to Atlassian, the CIA had not revoked his access as an Administrator to ESXi, which is what he used to be able to do the reversion.

Emotion

In Schulte’s first trial, it seems clear the jury hung based on nullification of one juror, who (according to some jurors) refused to deliberate fairly. DOJ stupidly presented the case in a way that emphasized the human resource dispute, and not the leak. And in a contest of popularity between the CIA and WikiLeaks, the CIA is never going to win 12 votes unanimously, certainly not in SDNY.

I had thought that Schulte would be able to recreate that dynamic with this trial, by once again portraying himself as the unfair victim of CIA bullying. But in at least one case, I think that attempt backfired (by showing Schulte to be precisely the insubordinate prick that the CIA claims him to be).

That said, given Furman’s response, Schulte did brilliantly portray the investigation into him as being biased. So he may win the emotional battle yet again. After he finished, Furman suggested that if Schulte were acquitted, he might have a future as a defense attorney.

THE COURT: You may be seated. All right. Mr. Schulte, that was very impressive, impressively done.

MR. SCHULTE: Thank you.

THE COURT: Depending on what happens here, you may have a future as a defense lawyer. Who knows?

Tactics

In a recent New Yorker profile of Schulte, Sabrina Shroff described how by going pro se, Schulte would be able to push boundaries that she herself could not.

When you consider the powerful forces arrayed against him—and the balance of probabilities that he is guilty—Schulte’s decision to represent himself seems reckless. But, for the C.I.A. and the Justice Department, he remains a formidable adversary, because he is bent on destroying them, he has little to lose, and his head is full of classified information. “Lawyers are bound,” Shroff told me. “There are certain things we can’t argue, certain arguments we can’t make. But if you’re pro se ”—representing yourself—“you can make all the motions you want. You can really try your case.”

Schulte did this repeatedly. He did so with classified information, as when he tried to get “Jeremy Weber” to admit to a report by a still-classified group that Weber was not aware of and which the government insists, to this day, does not exist undermined the attribution of the case (this is based off an out of context text that Weber was not privy to).

Q. Were there many forensic reports filed by AFD about the leak?

A. Not that I’m aware of.

Q. OK. But at some point you learned that AFD determined the backups from the Altabackups must have been stolen, correct?

MR. LOCKARD: Objection.

THE COURT: Sustained. (Defendant conferred with standby counsel)

BY MR. SCHULTE: Q. You reviewed the AFD reports, correct?

MR. LOCKARD: Objection.

THE COURT: Sustained. Let’s move on, Mr. Schulte. (Defendant conferred with standby counsel)

THE COURT: And please keep your voice down when conferring with standby counsel.

… with investigative details (both into his own and a presumed ongoing investigation into WikiLeaks) he has become privy to, such as when he suggested that a SysAdmin named Dave had lost a Stash backup.

Q. Speaking with the admins, you’re talking Dave, Dave C., right; he was one of those?

A. Yeah, Dave.

Q. And he was an employee who put the Stash on a hard drive, correct?

A. I know I’ve heard some of that. I don’t know exactly the situation around that, but —

Q. But that, basically this hard drive with Stash was lost, correct?

MR. DENTON: Objection.

THE COURT: Sustained.

… with testimony presented as questions, as here when Schulte tried to get Special Agent Evanchec to testify that his retention of an OIG email was an honest mistake.

Q. So in your career, classifying documents, sometimes people make honest mistakes when they classify documents, correct?

MR. LOCKARD: Objection.

A. I think that’s —

THE COURT: Sustained.

BY MR. SCHULTE: Q. Have you ever made a mistake classifying a document, sir?

MR. LOCKARD: Objection.

THE COURT: Sustained.

BY MR. SCHULTE: Q. Do you know if someone makes an honest mistake in classifying a document, if they can be charged with a crime?

MR. LOCKARD: Objection.

THE COURT: Sustained.

… and with speculative claims about alternative theories, such as here when he mocked jail informant Carlos Betances’ claim that Schulte said he needed Russian help for what he wanted to accomplish.

Q. OK. Next, you testified on direct that I told you the Russians would have to help me for the work I was doing, right?

A. Yes, correct.

Q. OK. So the Russians were going to send paratroopers into New York and break me out of MCC?

MR. LOCKARD: Objection.

THE COURT: Sustained.

Over and over, prosecutors objected when Schulte made such claims, and most often their objections were sustained. But I think it highly unlikely jurors will be able to entirely unhear many of the speculative claims Schulte made, and so while some of the claims Schulte presented in such fashion were outright false, the jury is unlikely to be able to fully ignore that information.

The unsaid

There are three things that didn’t happen at the trial that I’m quite fascinated by.

First, after delaying the trial for at least four months so as to be able to use Steve Bellovin as his expert, Schulte didn’t even submit an expert report for him. There are many possible explanations for this — that Schulte didn’t like what Bellovin would have said, that Schulte used Bellovin, instead, as a hyper-competent forensic source to check his own theories but never intended to call him, or finally, that Schulte correctly judged he could serve as his own expert in questioning witnesses. That said, the fact that he didn’t use Bellovin makes the delay far more curious.

There are numerous instances — one example is a gotcha that Schulte staged about a purported error (but not a far more significant real error) one of the FBI agents in the case made about Schulte’s Google searches — that were actually quite incriminating. The government, unsurprisingly, didn’t distract from their main case to lay this out though. But I hope to return to some of these details because, while they are irrelevant to the verdict against Schulte (and I want to make clear are distinct from the jury’s ultimate decision about his innocence), they do provide interesting details about Schulte’s actions.

Finally, the government fought hard for the right to be able to present a Schulte narrative about what happened that he shared with his cousin, Shane Presnall, but didn’t introduce it at trial. Effectively, in the document Schulte exposed the real identity of one or more of his colleagues to his cousin. I’m not sure whether the government didn’t rely on this because they wanted to avoid the possibility Presnall would testify, they wanted to limit damage already done to the covert status of the CIA employees, or they didn’t want jeopardy to attach to the document (meaning they could use it in further charges in case of an acquittal). But I’d sure like to know why DOJ didn’t rely on it.

Note: As it did with the first trial, Calyx Institute made the transcripts available. This time, however, they were funded by Germany’s Wau Holland Foundation. WHF board member Andy Müller-Maguhn has been named in WikiLeaks operations and was in the US during some of the rough period when Schulte is alleged to have leaked these documents.