I’ve been getting into multiple Twitter fights about the term “fake news” of late, a topic about which I feel strongly but which I don’t have time to reargue over and over. So here are the reasons I find the term “fake news” to be counterproductive, even aside from the way Washington Post magnified it with the PropOrNot campaign amidst a series of badly reported articles on Russia that failed WaPo’s own standards of “fake news.”

Most people who use the term “fake news” seem to be fetishizing something they call “news.” By that, they usually mean the pursuit of “the truth” within an editor-and-reporter system of “professional” news reporting. Even in 2017, they treat that term “news” as if it escapes all biases, with some still endorsing the idea that “objectivity” is the best route to “truth,” even in spite of the way “objectivity” has increasingly imposed a kind of both-sides false equivalence that the right has used to move the Overton window in recent years.

I’ve got news (heh) for you America. What we call “news” is one temporally and geographically contingent genre of what gets packaged as “news.” Much of the world doesn’t produce the kind of news we do, and for good parts of our own history, we didn’t either. Objectivity was invented as a marketing ploy. It is true that during a period of elite consensus, news that we treated as objective succeeded in creating a unifying national narrative of what most white people believed to be true, and that narrative was tremendously valuable to ensure the working of our democracy. But even there, “objectivity” had a way of enforcing centrism. It excluded most women and people of color and often excluded working class people. It excluded the “truth” of what the US did overseas. It thrived in a world of limited broadcast news outlets. In that sense, the golden age of objective news depended on a great deal of limits to the marketplace of ideas, largely chosen by the gatekeeping function of white male elitism.

And, probably starting at the moment Walter Cronkite figured out the Vietnam War was a big myth, that elite narrative started developing cracks.

But several things have disrupted what we fetishize as news since them. Importantly, news outlets started demanding major profits, which changed both the emphasis on reporting and the measure of success. Cable news, starting especially with Fox but definitely extending to MSNBC, aspired to achieve buzz, and even explicitly political outcomes, bringing US news much closer to what a lot of advanced democracies have — politicized news.

And all that’s before 2002, what I regard as a key year in this history. Not only was traditional news struggling in the face of heightened profit expectations even as the Internet undercut the press’ traditional revenue model. But at a time of crisis in the financial model of the “news,” the press catastrophically blew the Iraq War, and did so at a time when people like me were able to write “news” outside of the strictures of the reporter-and-editor arrangement.

I actually think, in an earlier era, the government would have been able to get away with its Iraq War lies, because there wouldn’t be outlets documenting the errors, and there wouldn’t have been ready alternatives to a model that proved susceptible to manipulation. There might eventually have been a Cronkite moment in the Iraq War, too, but it would have been about the conduct of the war, not also about the gaming of the “news” process to create the war. But because there was competition, we saw the Iraq War as a journalistic failure when we didn’t see earlier journalistic complicity in American foreign policy as such.

Since then, of course, the underlying market has continued to change. Optimistically, new outlets have arisen. Some of them — perhaps most notably HuffPo and BuzzFeed and Gawker before Peter Thiel killed it — have catered to the financial opportunities of the Internet, paying for real journalism in part with clickbait stories that draw traffic (which is just a different kind of subsidy than the family-owned project that traditional newspapers often relied on, and these outlets also rely on other subsidies). I’m pretty excited by some of the journalism BuzzFeed is doing right now, but it’s worth reflecting their very name nods to clickbait.

More importantly, the “center” of our national — indeed, global — discourse shifted from elite reporter-and-editor newspapers to social media, and various companies — almost entirely American — came to occupy dominant positions in that economy. That comes with the good and the bad. It permits the formulation of broader networks; it permits crisis on the other side of the globe to become news over here, in some but not all spaces, it permits women and people of color to engage on an equal footing with people previously deemed the elite (though very urgent digital divide issues still leave billions outside this discussion). It allows our spooks to access information that Russia needs to hack to get with a few clicks of a button. It also means the former elite narrative has to compete with other bubbles, most of which are not healthy and many of which are downright destructive. It fosters abuse.

But the really important thing is that the elite reporter-and-editor oligopoly was replaced with a marketplace driven by a perverse marriage of our human psychology and data manipulation (and often, secret algorithms). Even assuming net neutrality, most existing discourse exists in that marketplace. That reality has negative effects on everything, from financially strapped reporter-and-editor outlets increasingly chasing clicks to Macedonian teenagers inventing stories to make money to attention spans that no longer get trained for long reads and critical thinking.

The other thing to remember about this historical narrative is that there have always been stories pretending to present the real world that were not in fact the real world. Always. Always always always. Indeed, there are academic arguments that our concept of “fiction” actually arises out of a necessary legal classification for what gets published in the newspaper. “Facts” were insults of the king you could go to prison for. “Fiction” was stories about kings that weren’t true and therefore wouldn’t get you prison time (obviously, really authoritarian regimes don’t honor this distinction, which is an important lesson in their contingency). I have been told that fact/fiction moment didn’t happen in all countries, and it happened at different times in different countries (roughly tied, in my opinion, to the moment when the government had to sustain legitimacy via the press).

But even after that fact/fiction moment, you would always see factual stories intermingling with stuff so sensational that we would never regard it as true. But such sensational not-true stories definitely helped to sell newspapers. Most people don’t know this because we generally learn a story via which our fetishized objective news is the end result of a process of earlier news, but news outlets — at least in the absence of heavy state censorship — have always been very heterogeneous.

As many of you know, a big part of my dissertation covered actual fiction in newspapers. The Count of Monte-Cristo, for example, was published in France’s then equivalent of the WSJ. It wasn’t the only story about an all powerful figure with ties to Napoleon Bonaparte that delivered justice that appeared in newspapers of the day. Every newspaper offered competing versions, and those sold newspapers at a moment of increasing industrialization of the press in France. But even at a time when the “news” section of the newspaper presented largely curations of parliamentary debates, everything else ran the gamut from “fiction,” to sensational stuff (often reporting on technology or colonies), to columns to advertisements pretending to be news.

After 1848 and 1851, the literary establishment put out alarmed calls to discipline the literary sphere, which led to changes that made such narratives less accessible to the kind of people who might overthrow a king. That was the “fictional narrative” panic of the time, one justified by events of 1848.

Anyway, if you don’t believe me that there has always been fake news, just go to a checkout line and read the National Enquirer, which sometimes does cover people like Hillary Clinton or Angela Merkel. “But people know that’s fake news!” people say. Not all, and not all care. It turns out, some people like to consume fictional narratives (I have actually yet to see analysis of how many people don’t realize or care that today’s Internet fake news is not true). In fact, everyone likes to consume fictional narratives — it’s a fundamental part of what makes us human — but some of us believe there are norms about whether fictional narratives should be allowed to influence how we engage in politics.

Not that that has ever stopped people from letting religion — a largely fictional narrative — dictate political decisions.

So to sum up this part of my argument: First, the history of journalism is about the history of certain market conditions, conditions which always get at least influenced by the state, but which in so-called capitalist countries also tend to produce bottle necks of power. In the 50s, it was the elite. Now it’s Silicon Valley. And that’s true not just here! The bottle-neck of power for much of the world is Silicon Valley. To understand what dictates the kinds of stories you get from a particular media environment, you need to understand where the bottle-necks are. Today’s bottle-neck has created both what people like to call “fake news” and a whole bunch of other toxins.

But also, there has never been a time in media where not-true stories didn’t comingle with true stories, and at many times in history the lines between them were not clear to many consumers. Plus, not-true stories, of a variety of types, can often have a more powerful influence than true ones (think about how much our national security state likes series like 24). Humans are wired for narrative, not for true or false narrative.

Which brings us to what some people are calling “fake news” — as if both “fake” and “news” aren’t just contingent terms across the span of media — and insisting it has never existed before. These people suggest the advent of deliberately false narratives, produced both by partisans, entrepreneurs gaming ad networks, as well as state actors trying to influence our politics, narratives that feed on human proclivity for sensationalism (though stories from this year showed Trump supporters had more of this than Hillary supporters) served via the Internet, are a new and unique threat, and possibly the biggest threat in our media environment right now.

Let me make clear: I do think it’s a threat, especially in an era where local trusted news is largely defunct. I think it is especially concerning because powers of the far right are using it to great effect. But I think pretending this is a unique moment in history — aside from the characteristics of the marketplace — obscures the areas (aside from funding basic education and otherwise fostering critical thinking) that can most effectively combat it. I especially encourage doing what we can to disrupt the bottle-neck — one that happens to be in Silicon Valley — that plays on human nature. Google, Facebook, and Germany have all taken initial steps which may limit the toxins that get spread via a very American bottle-neck.

I’m actually more worried about the manipulation of which stories get fed by big data. Trump claims to have used it to drive down turnout; and the first he worked with is part of a larger information management company. The far right is probably achieving more with these tailored messages than Vladimir Putin is with his paid trolls.

The thing is: the antidote to both of these problems is to fix the bottle-neck.

But I also think that the most damaging non-true news story of the year was Bret Baier’s claim that Hillary was going to be indicted, as even after it was retracted it magnified the damage of Jim Comey’s interventions. I always raise that in Twitter debates, and people tell me oh that’s just bad journalism not fake news. It was a deliberate manipulation of the news delivery system (presumably by FBI Agents) in the same way the manipulation of Facebooks algorithms feeds so-called fake news. But it had more impact because more people saw it and people may retain news delivered as news more. It remains a cinch to manipulate the reporter-and-editor news process (particularly in an era driven by clicks and sensationalism and scoops), and that is at least as major a threat to democracy as non-elites consuming made up stories about the Pope.

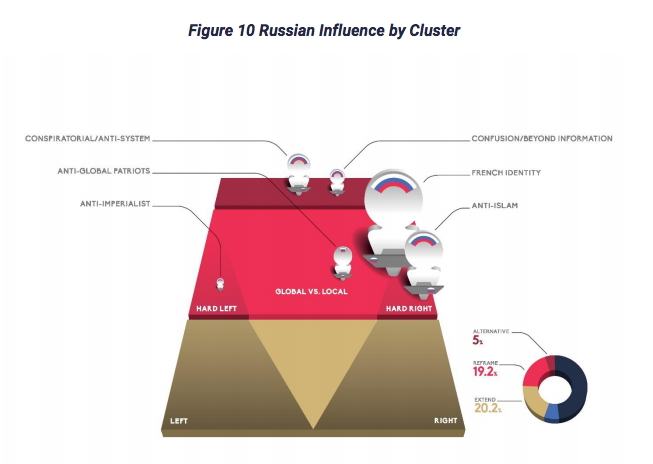

I’ll add that there are special categories of non-factual news that deserve notice. Much stock market reporting, especially in the age of financialization, is just made up hocus pocus designed to keep the schlubs whom the elite profit off of in the market. And much reporting on our secret foreign policy deliberately reports stuff the reporter knows not to be true. David Sanger’s recent amnesia of his own reporting on StuxNet is a hilarious example of this, as is all the Syria reporting that pretends we haven’t intervened there. Frankly, even aside from the more famous failures, a lot of Russian coverage obscures reality, which discredits reports on what is a serious issue. I raise these special categories because they are the kind of non-true news that elites endorse, and as such don’t raise the alarm that Macedonian teenagers making a buck do.

The latest panic about “fake news” — Trump’s labeling of CNN and Buzzfeed as such for disseminating the dossier that media outlets chose not to disseminate during the election — suffers from some of the same characteristics, largely because parts of it remain shrouded in clandestine networks (and because the provenance remains unclear). If American power relies (as it increasingly does) on secrets and even outright lies, who’s to blame the proles for inventing their own narratives, just like the elite do?

Two final points.

First, underlying most of this argument is an argument about what happens when you subject the telling of true stories to certain conditions of capitalism. There is often a tension in this process, as capitalism may make “news” (and therefore full participation in democracy) available to more people, but to popularize that news, businesses do things that taint the elite’s idealized notion of what true story telling in a democracy should be. Furthermore, at no moment in history I’m aware of has there been a true “open” market for news. It is always limited by the scarcity of outlets and bandwidth, by laws, by media ownership patterns, and by the historically contingent bottle-necks that dictate what kind of news may be delivered most profitably. One reason I loathe the term “fake news” is because its users think the answer lies in non-elite consumers or in producers and not in the marketplace itself, a marketplace created in and largely still benefitting the US. If “fake news” is a problem, then it’s a condemnation of the marketplace of ideas largely created by the US and elites in the US need to attend to that.

Finally, one reason there is such a panic about “fake news” is because the western ideology of neoliberalism has failed. It has led to increased authoritarianism, decreased quality of life in developed countries (but not parts of Africa and other developing nations), and it has led to serial destabilizing wars along with the refugee crises that further destabilize Europe. It has failed in the same way that communism failed before it, but the elites backing it haven’t figured this out yet. I’ll write more on this (Ian Welsh has been doing good work here). All details of the media environment aside, this has disrupted the value-laden system in which “truth” exists, creating a great deal of panic and confusion among the elite that expects itself to lead the way out of this morass. Part of what we’re seeing in “fake news” panic stems from that, as well as a continued disinterest in accountability for the underlying policies — the Iraq War and the Wall Street crash and aftermath especially — enabled by failures in our elite media environment. But our media environment is likely to be contested until such time as a viable ideology forms to replace failed neoliberalism. Sadly, that ideology will be Trumpism unless the elite starts making the world a better place for average folks. Instead, the elite is policing discourse-making by claiming other things — the bad true and false narratives it, itself, doesn’t propagate — as illegitimate.

“Fake news” is a problem. But it is a minor problem compared to our other discursive problems.