“Something Like This Has 0 Repercussions if You Mess Up:” John Durham Debunked the Alfa Bank Debunkery

As you know, John Durham failed spectacularly in trying to use a false statement charge against Michael Sussmann to cement a wild conspiracy theory against the Democrats.

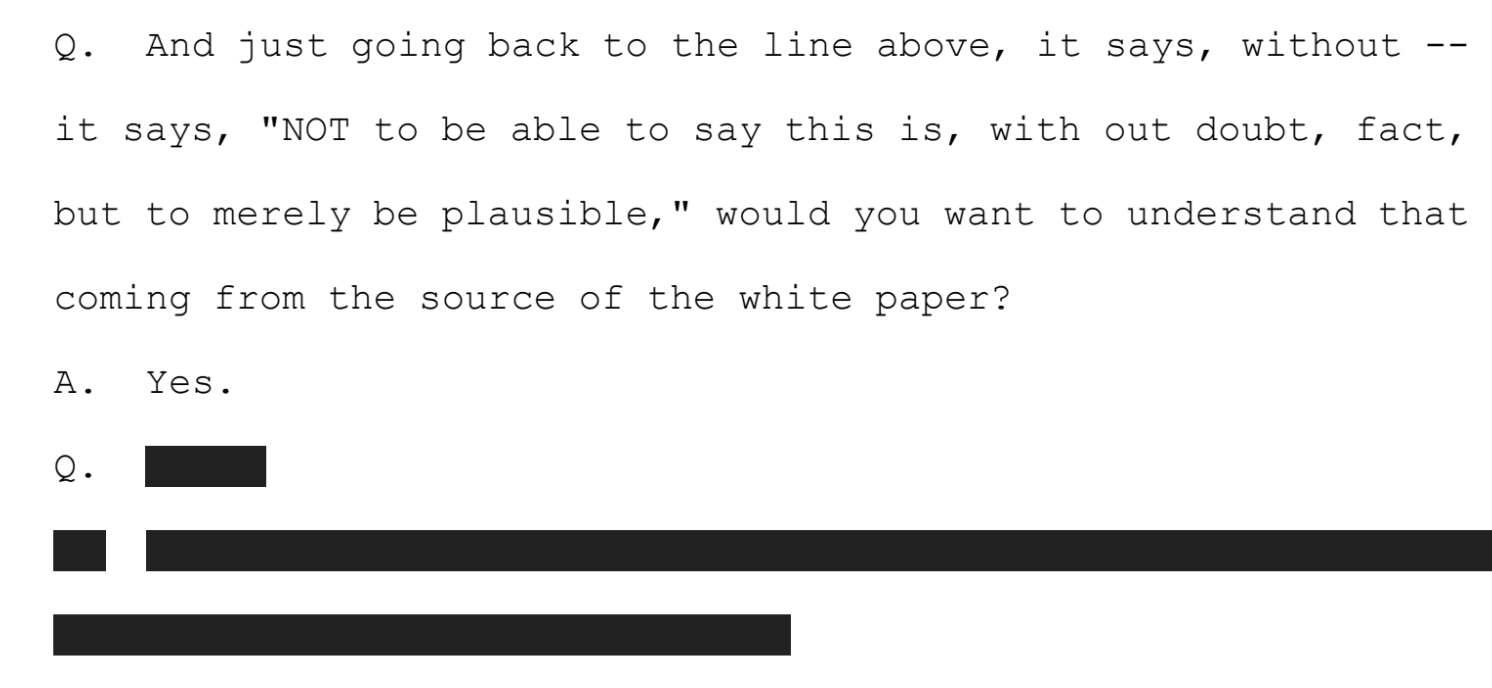

But Durham did succeed in one thing (though you wouldn’t know it from some of the reporting from the trial): He utterly discredited the FBI investigation into the Alfa Bank allegations. Lead prosecutor Andrew DeFilippis even conceded as much in his closing argument.

Now, ladies and gentlemen, you have heard testimony about how the FBI handled this investigation. And, ladies and gentlemen, you’ve seen that the FBI didn’t necessarily do everything right here. They missed opportunities. They made mistakes. They even kept information from themselves.

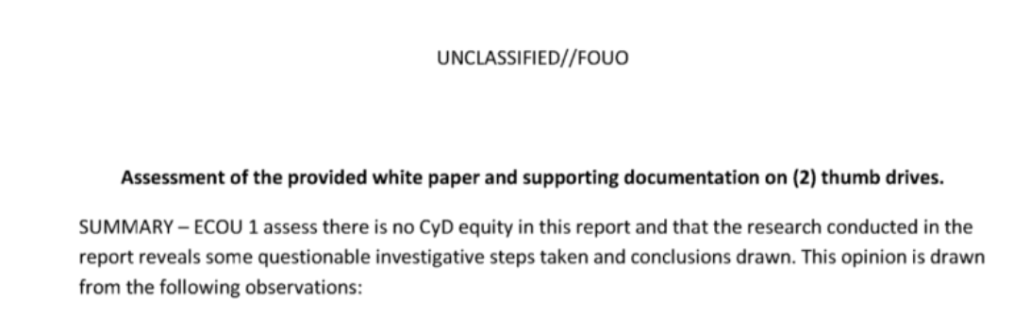

That’s a fairly stunning concession from DeFilippis. After all, DeFilippis asked the guy who was responsible for some of the worst failures in the investigation, Scott Hellman, to be his expert witness, even though Hellman, by his own admission, only “kn[e]w the basics” of the DNS look-ups at the heart of the investigation. Along with Nate Batty, Hellman wrote an analysis of the Alfa Bank white paper in less than a day that:

- Misstated the methodology behind the white paper

- Blew off a reference to “global nonpublic DNS activity” that should have been a tip-off about the kinds of people behind the white paper

- Falsely claimed that the anomaly had only started three weeks before the white paper when in fact it went back months

- Asserted that there was no evidence of a hack even though a hack is one of the hypotheses presented in the white paper for the anomaly at Spectrum Health (Spectrum itself said the look-ups were the result of a misconfigured application)

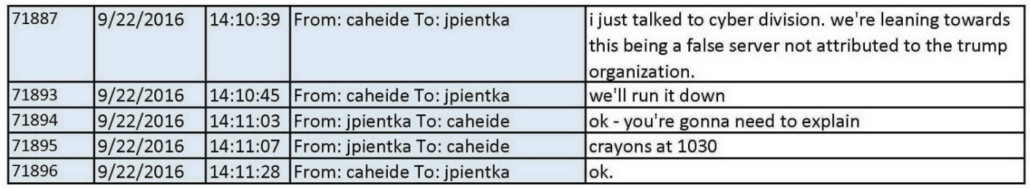

Later testimony showed that, after speaking to Hellman and before even checking whois records, the Chicago-based agent who had a lead role in the investigation told a supervisor that “we’re leaning towards this being a false server.”

Within hours, Miami-based agents had confirmed with Cendyn that was false.

In spite of being so egregiously misled from the start by the guys in Cyber, agent Curtis Heide testified in cross-examination by Sussman’s attorney, Sean Berkowitz, that Hellman’s analysis was one of the four things that he believed supported a finding that the anomaly was not substantiated.

Q. Okay. I think near the end of your examination by Mr. Algor he questioned you about your basis for concluding that there was — that the allegations were unsubstantiated. And I think you gave four reasons. I’m going to run through them. If there’s more, that’s okay. Number one, you said the assessment done by Agents Hellman and Batty. Correct?

A. Yes.

Q. Two, the review of the logs. Correct?

A. Yes.

Q. Three, the Mandiant conclusion. Correct?

A. Yes.

Q. And four, the discussions with Spectrum Health about the TOR node. Correct?

A. Yes.

Q. Anything else that you can recall, sir, as to why it was that your investigation, or rather the investigation that you oversaw, suggested that the allegations were unsubstantiated?

A. The only other thing I can think of would be my training and experience with — relating to Russia and cyber investigations.

Q. And is there anything in particular about that that you recall today?

A. With respect to the white paper, it didn’t — when I read through it initially, I had several questions, and it didn’t appear to be consistent with Russian TTPs.

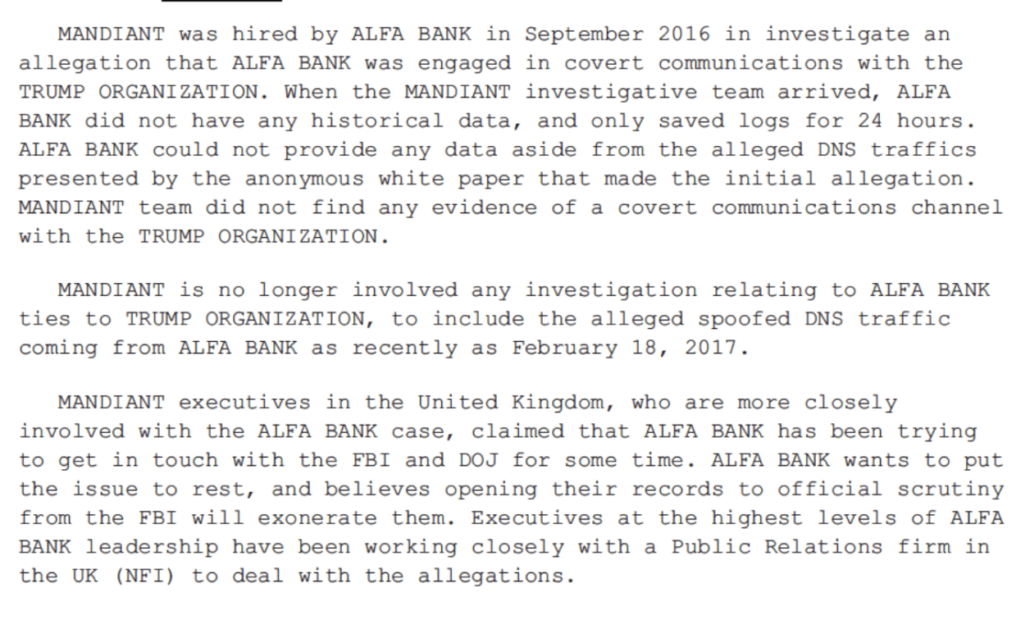

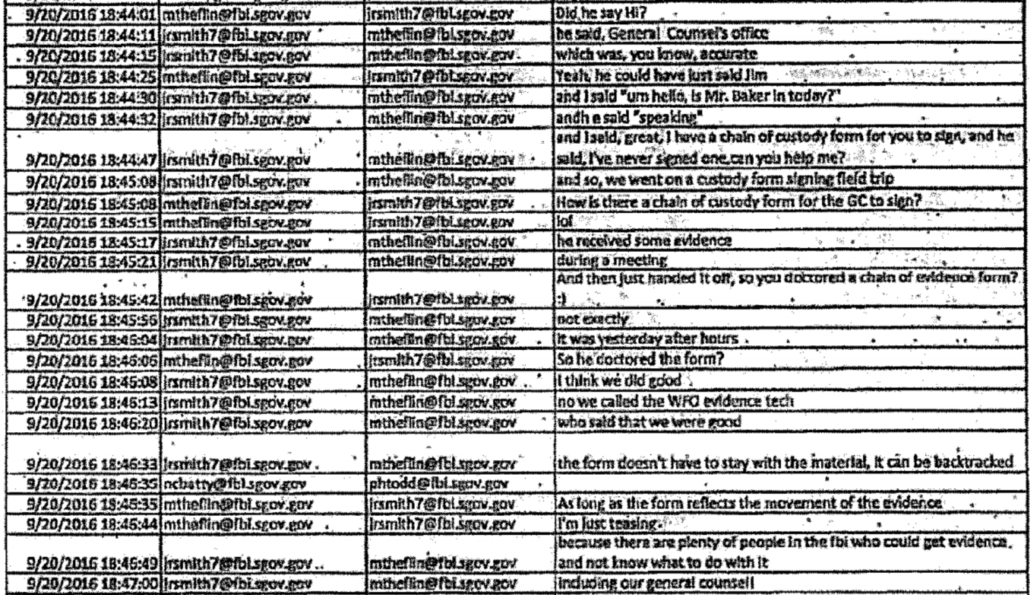

Another thing Heide relied on was the analysis from Mandiant, which Alfa Bank hired to investigate after NYT reached out. According to Franklin Foer’s story, Lichtblau reached out to Alfa on September 21, after Sussmann had given the FBI a heads up but before the FBI asked Lichtblau to hold the story on September 26, so in the window when the FBI had a chance — but failed — to protect the investigation.

One of the truly insane parts of this investigation, by the way — which was conducted entirely during the pre-election window when overt actions were prohibited — was that FBI big-footed to Cendyn and Listrak before sending NSLs to them. And by that point, Alfa Bank was calling the FBI.

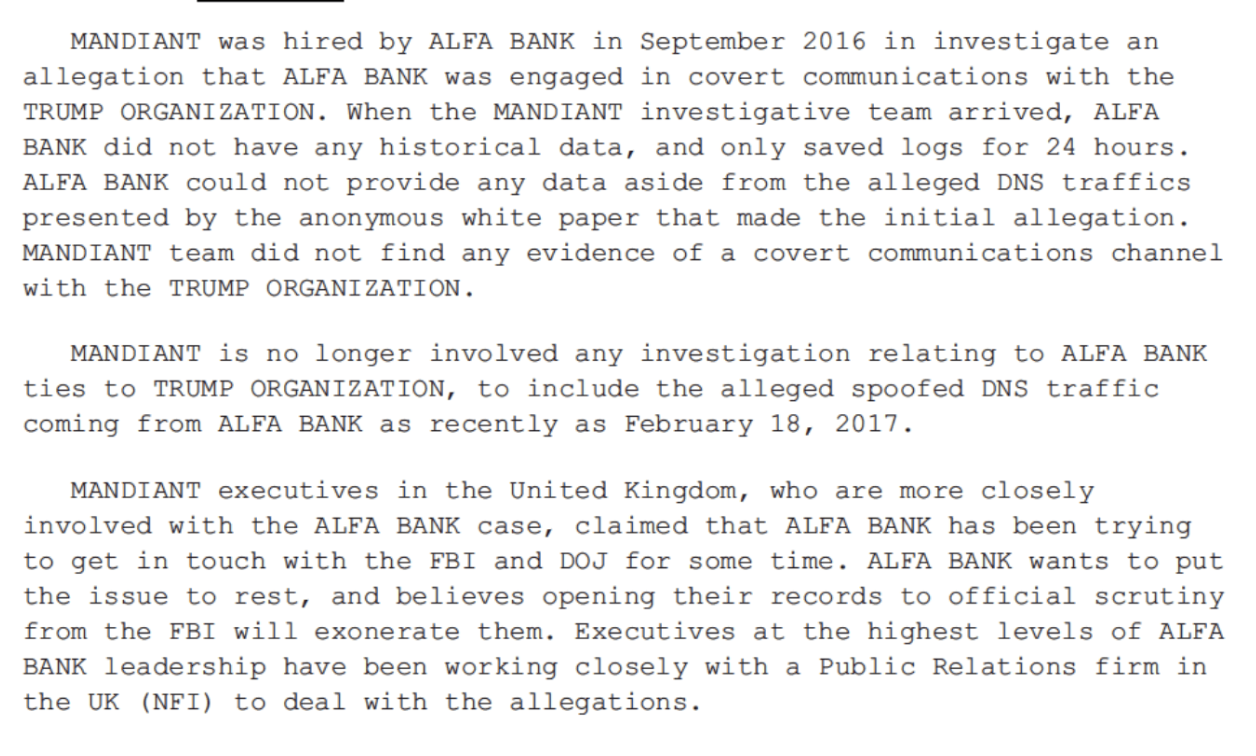

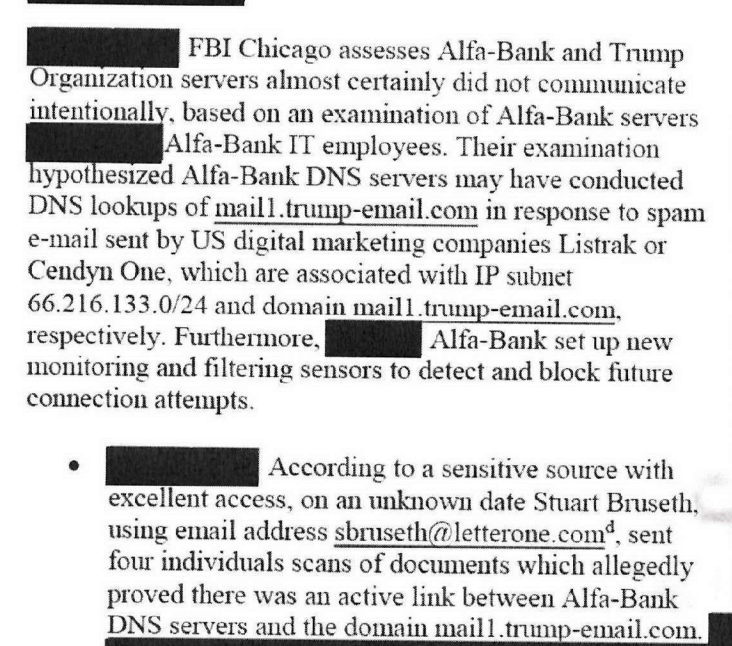

A report that was not explained amid the primary resources from the investigation, but which was concluded by October 3, reveals that Chicago’s conclusion was almost entirely based on what Alfa told the FBI and Mandiant.

There was nothing in the case documentation until a 302 for a March 27, 2017 interview done in association with Alfa’s 2017 claims of spoofed DNS traffic (the interview may have been done with Kirkland and Ellis) that documented that, when Mandiant arrived the previous year to investigate, there were no logs to investigate.

Indeed, Heide testified on cross-examination that he had never learned of that fact. At all.

Q. And were you aware, while you were doing the investigation, that Mandiant, when it went to talk to AlfaBank to look into these allegations, did not have any historical data, that Alfa-Bank did not provide any historical data to Mandiant? Did you know that?

A. No

We now know that at a time when “Executives at the highest level of ALFA BANK leadership” had been hoping to “exonerate them[selves]” in 2017, Petr Aven had already started acting on specific directives from Vladimir Putin, including trying to open a back channel to Trump.

Plus, at least as far as Listrak could determine, while the marketing server had sent materials to Spectrum, it had never sent anything to Alfa Bank. The stated explanation that this was spam, then, conflicts with what FBI was seeing in the logs.

As for Spectrum — another of the reasons Heide pointed to — there’s no evidence of anyone reaching out to them (as compared to interactions with agents in Philadelphia and Miami who reached out to Listrak and Cendyn, respectively).

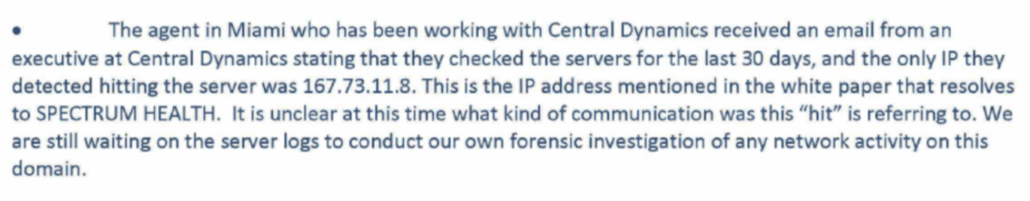

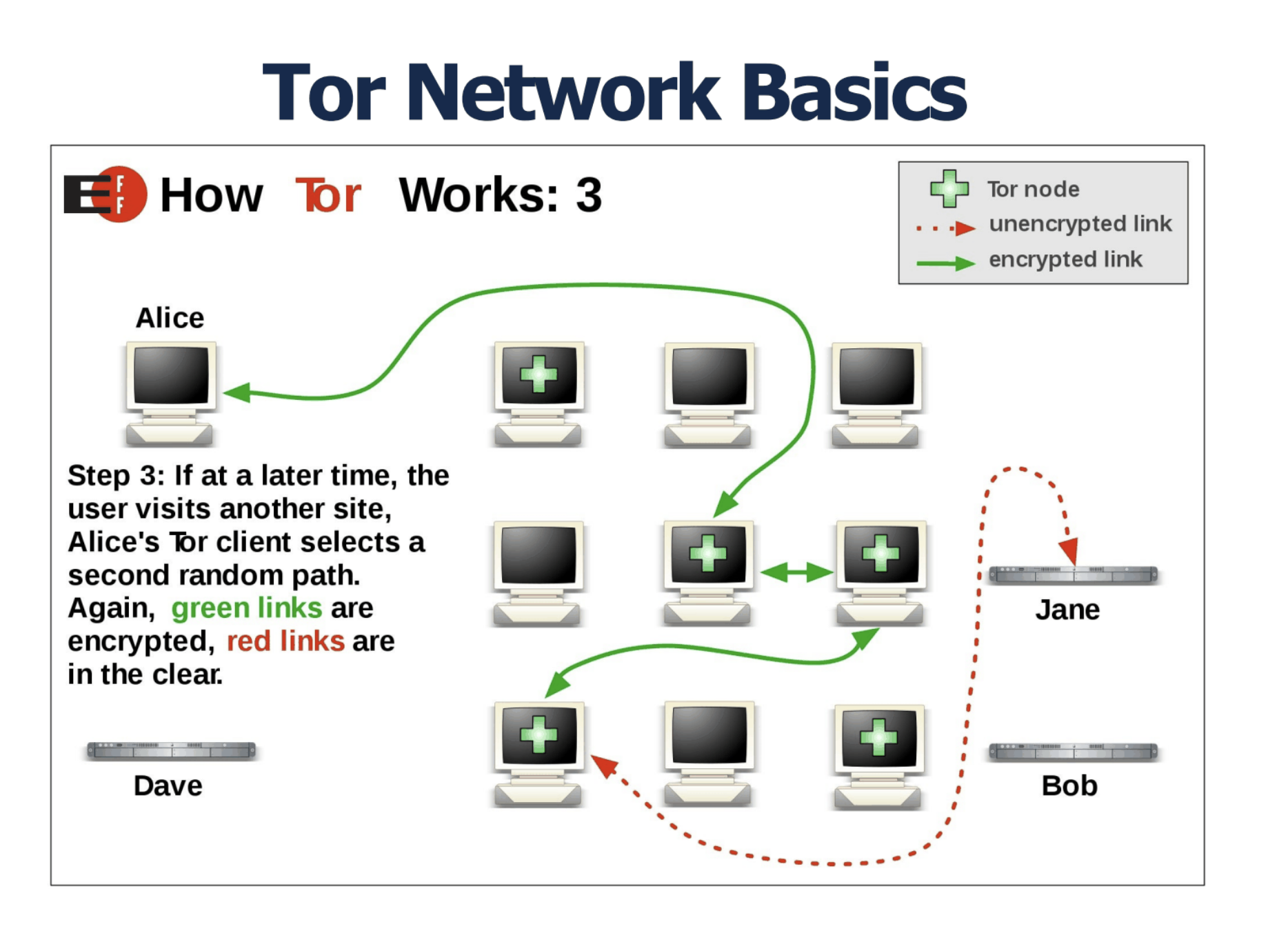

It’s true that the anomaly at Spectrum was not a Tor node (something that researchers came to understand themselves around the time Sussmann shared the allegations with the FBI). But it’s also true that, per Cendyn (which only looked back a month), the identified IP address at Spectrum was reaching out to the Trump server.

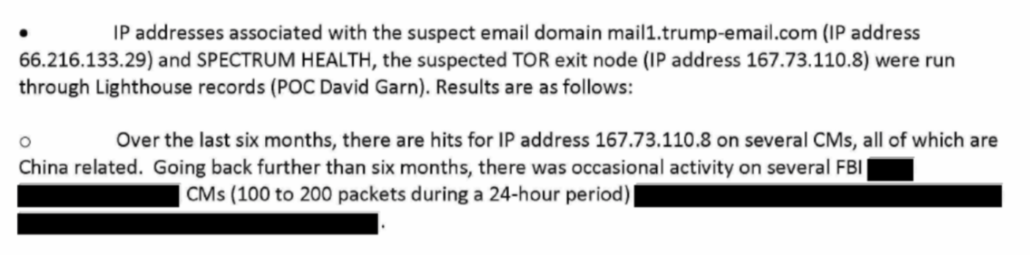

The IP address in question showed up in traffic that may be associated with Chinese hacking.

This then might have corroborated the hypothesis, from the white paper, of a hack of Spectrum, but by this point, Hellman had long before decided there was no evidence of a hack and this was, “just garbage.”

That leaves the logs, Heide’s fourth reason for believing FBI had debunked the Alfa Bank allegations. As far as the logs in question, former agent Allison Sands (who was assigned the investigation as a brand new case agent) told one of the tech people on September 26 that, “the end user [possibly Cendyn] is willing to provide logs but they dont have what we need.” Cendyn did share details of their own spam filter, which wouldn’t address the DNS look-ups themselves.

Then, on October 12, Sands told Heide that,

the ‘logs’ we got from Listrak were not network logs

they basically just confirm that trump org is one of their email clients, but they dont show destination email addresses or IPs or anything that we can use to[ ]determine any communications

[snip]

it was two excel spreadsheets

that was all we got

The FBI did get something. Sands testified that the FBI obtained upwards of 600,000 records (she described obtaining records from Cendyn, Listrak, and GoDaddy, but not Spectrum or Alfa Bank). But it’s not clear how useful those records really were. There’s a reference to the “take” elsewhere (see below), and redacted entries that look like intelligence targeting, plus a reference to an OGA partner reporting “no attempts.” (Here’s a reference to the OGA analysis that is redacted in other versions of the same email chain.) So it seems any useful logs came from another agency. But if that’s right, it would be targeted overseas.

In trial testimony, Sands described that her task was to prove that the allegation wasn’t true, not to explain what the anomaly was.

I knew still I had to rebuild from scratch and prove that this allegation wasn’t true.

In real time, too, she saw her task as disproving that emails had been shared, not even disproving that covert communication had occurred.

I have a few more logs to definitely prove there are no emails, and then Im putting it to bed

That’s a particularly problematic description given that the FBI had been told via other channels that there was some activity reflecting more than DNS look-ups.

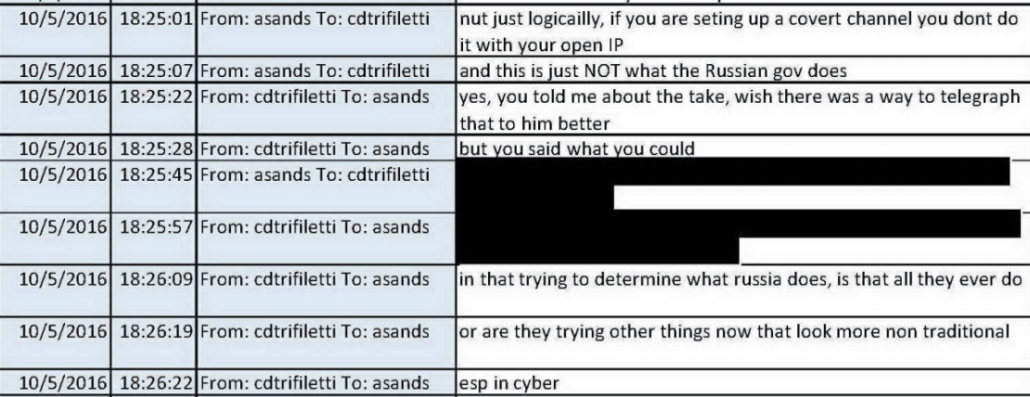

That leaves, according to Heide’s judgement, just the observation that the DNS traffic was not consistent with known Russian techniques. Newbie agent Sands said something similar to Chris Trifiletti, Joffe’s handler and apparently sensitive for some other reasons. In response, he mused about whether Russia was “trying other things now that look more non traditional.”

We don’t know the answer to that, because the FBI didn’t try to figure it out.

Scott Hellman, the cyber agent who insisted at every opportunity he got that this was garbage was wrong about how long the anomaly had lasted, but he was right about one thing. On October 4, he advised newbie agent Sands that,

any chance you get to work something like this that truly has 0 repercussions if you mess it up ….take those opportunities

He did mess it up. It wasn’t just his own analysis; his repeated insistence that this was “garbage” appears to have made all the other investigators less careful, too. Six years later, we’re still no closer to understanding what happened.

Hellman was right about facing “zero repercussions if you mess it up.” By all appearances, he’s one of the few people who escaped any consequences for trying to investigate Russia in 2016. We know that several people — including Jim Comey, Andrew McCabe, Peter Strzok, and Bruce Ohr — were fired for their efforts to investigate Russia. We learned at the trial that Ryan Gaynor was threatened with criminal investigation for not answering questions the way Andrew DeFilippis wanted. Curtis Heide remains under FBI Inspection Division investigation for things he did in 2016. Rodney Joffe was discontinued as an FBI informant, according to him, at least, because he refused to cooperate with Durham’s investigation. Everyone who actually tried to investigate Russia in 2016 has faced adverse consequences.

But Hellman appears to have suffered none of those adverse consequences for fucking up an investigation into a still unexplained anomaly. On the contrary, he’s been promoted; he’s now a Supervisory Special Agent, leading a team of people who will, presumably, similarly blow off anomalies that might be politically inconvenient to investigate.

That’s the lesson of the Sussmann trial then: The only people who face zero consequences are the ones who fuck up.

Update: Corrected spelling of Hellman’s last name. Added Comey and McCabe to the list of those fired for investigating Russia. Removed Lisa Page–she quit before she was fired. In this podcast, Peter Strzok said that all FBI agents named in the DOJ IG Report are still under investigation.

Update: All the links to exhibits should be live now.

Update: Added detail that Listrak says Trump never sent marketing mail to Alfa Bank.

Timeline

I’ve put (what I believe are) all the exhibits about the FBI investigation below.

These times are surely not all correct. Durham consistently shared evidence without marking what time zone the evidence reflected. Importantly, some, but probably not all of the FBI Lync messages reflect UTC time; where I was fairly certain, I tried to reflect the time in ET, but in others, the timeline below doesn’t make sense (I’ll keep tweaking it). Some of the emails reflect the Chicago time zone.

September 19, 2:00PM: Sussmann Meeting

September 19: Priestap notes

September 19: Anderson notes

September 19, 3:00PM: Strzok accepts materials

September 19, 4:31PM: Gessford to Pientka: Moffa with info dropped off to Baker

September 19, 5:00PM: Sporre accepts materials

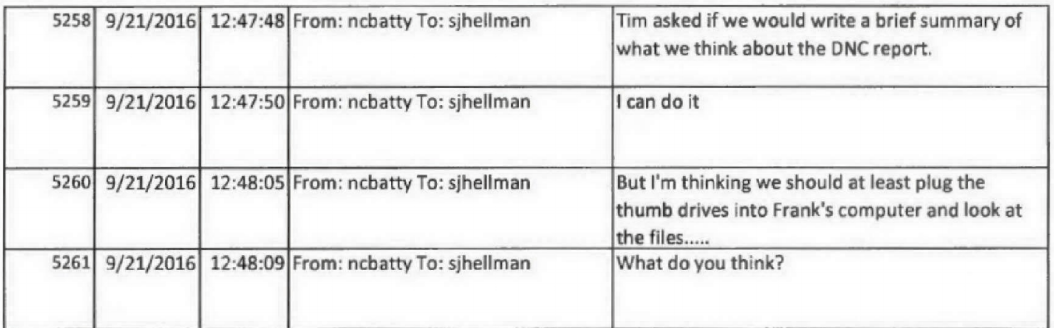

September 20, 9:30AM: Nate Batty to Jordan Smith: A/AD has two thumb drives.

September 20, 12:29PM: Batty accepts materials

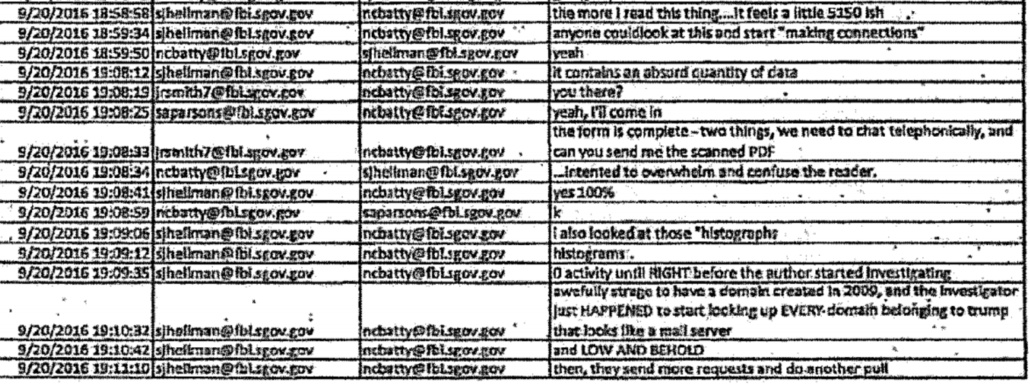

September 20, 4:54PM: Batty and Hellman re analysis

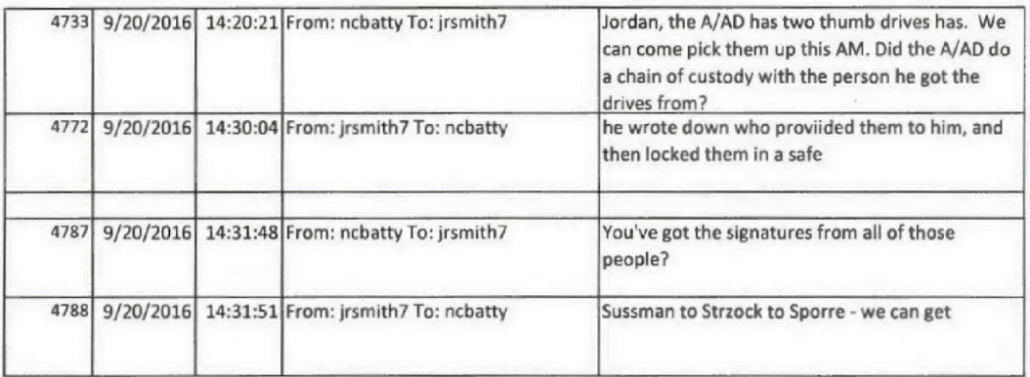

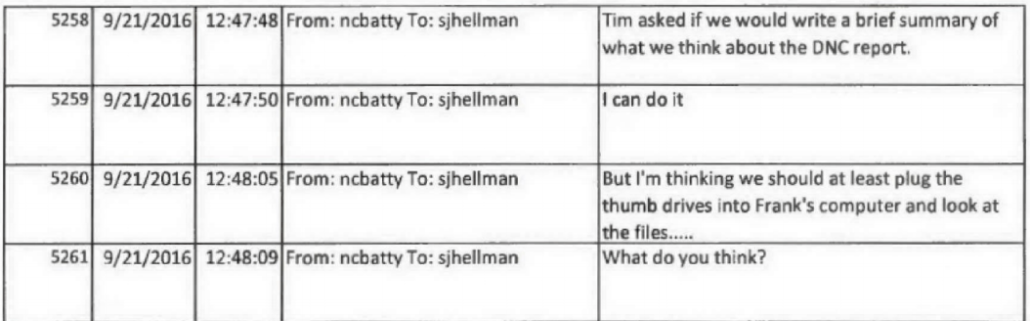

September 21, 8:48AM: Batty to Hellman: at least look at the thumb drives [Batty Lync]

September 21, 4:25PM: Pientka Lync to Heide: People on 7th floor fired up about this server

September 21, 4:46PM: Batty to Heide and others: initial assessment

September 21, 1:10PM [time uncertain] Sands to Pape: Director level interest

September 21, 4:57PM: Norwat to Todd: Not a cyber matter

September 21, 5:06PM: Todd to Heide, cc Pientka

September 21, 5:52PM: Pientka to Heide: Nat [sic] Batty ha the thumb drives

September 22, 4:58AM: Hubiak to Heide: Let me know if you need anything from PH

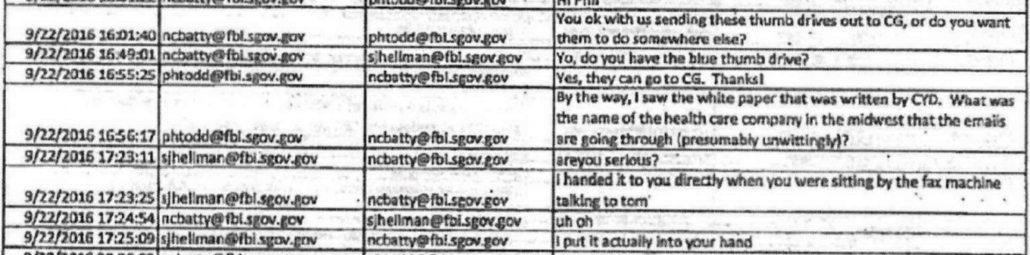

September 22, 8:09AM: Todd to Marasco [noting thumb drives came from DNC, suggesting tie to debate]

September 22, 8:33AM: Pientka to Heide: Less than 24 hours to investigate, determine nexus, before losing traffic, watched by Comey

September 22, 9:30AM: Pientka to Moffa: Cyber, ugh. Read first email.

September 22, 9:59PM: Hellman to Heide: can you talk on link

September 22, 10:23AM: Marasco to Pientka: FYI

September 22, 11:13AM: Sands to Hubiak: Suspect email domain hosted on Listrak server — if you can help out with a knock and talk it would be great.

September 22, 11:14AM: Baker to Comey and others: Reporter is Lichtblau

September22, 11:34AM: Hubiak to Sands: Will start working on this now

September 22, 12:02PM: Batty to Wierzbicki: We think it’s a setup

September 22, 12:10PM: Heide to Pientka: We’re leaning to this being a false server.

September 22, 2:00PM: Pientka to Hubiak: Thanks for all your efforts. The CROSSFIRE HURRICANE Team greatly appreciates you running this to ground.

September 22, 4:22PM: Sands to all: open full investigation, summary of Hellman’s conclusions [OGA partner targeting Alfa?]

September 22, 5:33PM: Heide to Pientka: it’s a legit domain

September 22, 4:53PM: Sands to all: Cendyn agrees to cooperate, legit mail server

September 23, 8:26AM: Sands to Hubiak: Cendyn willing to cooperate and provide logs

September 23, 1:09PM: Heide to Sands: once we get that case opened, let’s cut a lead to the MM division requesting assisting with the interview, etc.

September 23, 1:53PM: Sands to others: Cendyn, as of this morning no longer resolves, picture of Barracuda spam filter

September 23, 4:04PM: Heide to Gaynor: Cyber’s review

September 23: EC Opening Memo [without backup]

September 26: Gaynor notes

September 26: Intelligence Memo

September 26, 8:02AM: Lichtblau to Kortan: You know what time we’re meeting?

September 26, 9:29AM: Kortan to Lichtblau: Baker’s tied up until later this afternoon.

September 26, 10:02AM: Lichtblau to Kortan: planning to bring Steve Myers

September 26, 10:15: Heide to Pientka: We want to interview the source of the whitepaper?

September 26, 12:09: Kortan to Baker and Priestap: some kind of recap later today?

September 26, 12:29: Sands to Hubiak: I’m writing a justification for an NSL to GoDaddy

September 26, 4:19PM: Heide to Shaw: apparently it’s going to hit the times?

September 26, 4:55PM: Heide to Hellman: We think it’s a bunk report still…

September 26, 5:02PM: Soo to Sands: searching current and historical lists of Tor exit nodes

September 26, 6:20PM: Sands to all, cc Heide: Spectrum hit at Cendyn, NSLs for Listrak, GoDaddy, redacted, Tor results

October 2, 12:02PM: Grasso to Wierzbicki: Two IP addresses

October 2, 7:02PM: Heide to Hellman: Check this out….

October 3: Tactical Product

October 3: Communications Exploitation

October 3, 1:48PM: Gaynor to Heide: Did white paper start with person of interest?

October 3, 2:49PM: Heide to Gaynor and Sands: Interview source

October 3, 3:00PM: Wierzbicki to Gaynor, cc Moffa: I agree with Heide, interview source

October 4: Kyle Steere to Wierzbicki and Sands: Documenting contents of thumb drive

October 4, 8:26AM: Sands to Hellman: 2 random IP addresses we got from tom grasso

October 4, 8:28AM: Sands to Hellman: we got a report on the Alfa Bank side that they also think this is nothing

October 4, 8:43AM: Hellman to Sands: any chance you get to work something like this that truly has 0 repercussions if you mess it up ….take those opportunities [alt version]

October 4, 10:00AM: Gaynor to Wierzbicki et al, cc Moffa: We need to know what we can learn from the logs [CT version]

October 4, 9:50PM: Grasso to Sands: SME who can help give context to the data we discussed

October 4, 11:08PM: Sands to Grasso: Sounds great.

October 5, 1:20PM: Trifiletti to Sands: i reminded him once more that he has never proceeded with anything when he wasnt absolutely sure

October 5, 1:33PM: Hosenball request for comment

October 5, 3:02PM: Strzok to Gaynor, forwarding Hosenball with Mediafire package

October 5, 4:08PM: Sands to Trifiletti: We need to speak to Dave dagon now too

October 5, 5:07PM: Sands to all: Update on CHS conversation — redacted explanation for why Alfa changed

October 5, 6:58PM: Grasso to Sands: I told Dagon that you would be able to protect his identity so that his name is not made public

October 6: Gaynor notes and drawing [alt version, more redacted]

October 6, 4:20PM: Materials to storage

October 6, 4:28PM: Christopher Trifiletti: CHS report (Spectrum: misconfigured server)

October 6, 4:54PM: Trifiletti to Sands: Actual text of 1023 submitted

October 6, 6:21PM: Wierzbicki to Gaynor: CHS debrief

October 7, 8:59AM: Sands to Trifiletti

October 12, 8:01AM: Sands to Heide: the “logs” we got from listrak were not network logs

October 13, 5:45PM: Gaynor to Wierzbicki: Mediafire (includes link)

October 19, 8:05AM: Sands to Heide: we spoke to mandiant and that we are talkingt o [sic] the tech people at the ISP today

October 19, 10:15AM: Gaynor to Wierzbicki: 2 IP addresses, Mediafire, Dagon author?

November 1, 3:09PM: Sands to Trifiletti: I have a few more logs to definitely prove there are no emails, and then Im putting it to bed

November 14, 2:52PM: Steere to Sands: [report on September 30 receipt of logs from Cendyn]

January 18, 2017: Closing Memo

March 27, 2017: Sands 302 with Alfa reports that Mandiant reported no historic data

July 24, 2017: Moffa to Priestap: Includes several other reports

July 24, 2017, 3:10PM: Sands accepts custody